A Charmed Life

Chris Kraus

October 22, 2019

The best satire seems to spring from hatred and repugnance: Swift, Juvenal, Martial, Pope… Satire, I suspect, is usually written by powerless people. It is an act of revenge. – Mary McCarthy

I’ve always loved Mary McCarthy. She fit the—very tiny, exacting, exclusive— mold of the 20th-century female literary public intellectual. But unlike her approximate peers Susan Sontag or Simone de Beauvoir, she was a novelist first, a critic and theorist second, and her novels were ones that I actually wanted to read. McCarthy’s critical writing on literature is self-serving in the best possible way, that is, she reads like a writer, combing through literature of the past for validation of her own inclinations and work. She was a satirist, and (because also a woman) she was often accused of shrillness and hardness and unlikeability: she failed to be vulnerable enough in her work. People say this about women who write social comedy, still.

In essays like “Ideas and Literature,” McCarthy looked to Flaubert, Charles Dickens, George Eliot, Jane Austen as writers whose novels are grounded in fact. As different as these writers are, McCarthy said, “they have one thing in common: a deep love of fact.” Moving closer, she says, “The novel in its early stages almost always purports to be true.” And then, quoting Tolstoy: “The hero of my story is—the truth.” McCarthy was a warrior for truth, often at great personal cost. People loved her or hated her, and they hated her in the most passionate, articulate ways. “Tidings from the whore!” the writer Delmore Schwartz proclaimed whenever he opened the Partisan Review and found one of her new essays or stories.

Throughout her lifetime, Mary McCarthy’s work was deeply polarizing—people loved it or hated it—and it is still. Writing in the New York Times in 2000, years after her death, Larissa McFarquhar described her as “a viperously clever but minor writer, much admired, much detested.” And yet, her work was tremendously important to a generation of second wave feminist thinkers and writers, and generations beyond. Her first novel, The Company She Keeps, was republished in 2003. It’s a collection of linked stories about an ambitious, intelligent young woman’s life in New York. Although it was first published in 1942, McCarthy’s protagonist, Meg Sargent, is a close cousin to Lena Dunham in Girls, Kathy Acker in The Black Tarantula, Sheila Heti in How Should a Person Be?

Describing her lovers and friends in the most intimate detail, Company is a roman à clef with a very large key. Everyone in McCarthy’s extended New York circle of friends knew exactly who she was talking about. But these weren’t tales of revenge—the joke was mostly on Meg herself. I didn’t know about Company when I wrote I Love Dick in 1997—and when I discovered it later in 2003, I couldn’t believe this incredible resource had been withheld from me. It was all there. Claiming the freedom to speak about one’s own experience, even when, inevitably, others are involved. The imperfectability of the narrator. A comic narrative whose point isn’t confession or moral progress, but simply exposing the social dis/ease and real psychic pain that people experience every day. A novel that tells the truth... Isn’t that what people look for in literature? I taught it in class, bought copies for friends.

Writing in 2013, the writer and activist Vivian Gornick describes what a revelation Company was for her generation coming of age in the 1950s. “We read,” she reports, “two writers—Colette and Mary McCarthy—as others read the Bible: to learn better who we were and how, given the constraint of our condition, we were to live. Their novels and stories, collectively speaking, constitution our Book of Wisdom.”

Gornick continues: “The thing we prized most in McCarthy was the no-holds-barred honesty with which she nailed the situation. Who among us could not identify with Meg Sargent, bold as brass when she meets the Man in the Brooks Brothers Shirt on a train and then, next morning, is crawling around on his sleeping car floor, trying desperately to find her second stocking before he wakes up and forces her to face the humiliating complications of casual sex.”

Mary McCarthy is able to pin people down like odd insect specimens, summoning their essences with a single withering phrase. For example, in chapter six of The Group, Norine Schmittlapp, the trust-fund Marxist who’s sleeping with Kay’s husband, has golden brown eyes that were “were habitually narrowed, and her handsome, blowzy face had a plethoric look, as though darkened by clots of thought.” Or, in The Company She Keeps, Meg Sargent observes the tastefully dressed man on the overnight train she’ll soon sleep with and decide that he looked “like a middle-aged baby, like a young pig, like something in a seed catalog.” As her lifelong friend, the radical writer and editor Dwight MacDonald remarked in terror, “When most pretty girls smile at you, you feel terrific. When Mary smiles at you, you look to see if your fly is open.”

McCarthy is cruel to her subjects, but she’s never as cruel to them as she is to herself, and she’s present at all times in all of her fiction. She once replied, to the tiresome question asked only of women about how closely her novels hewed to real life: “What I really do is take real plums and put them in an imaginary cake.”

*

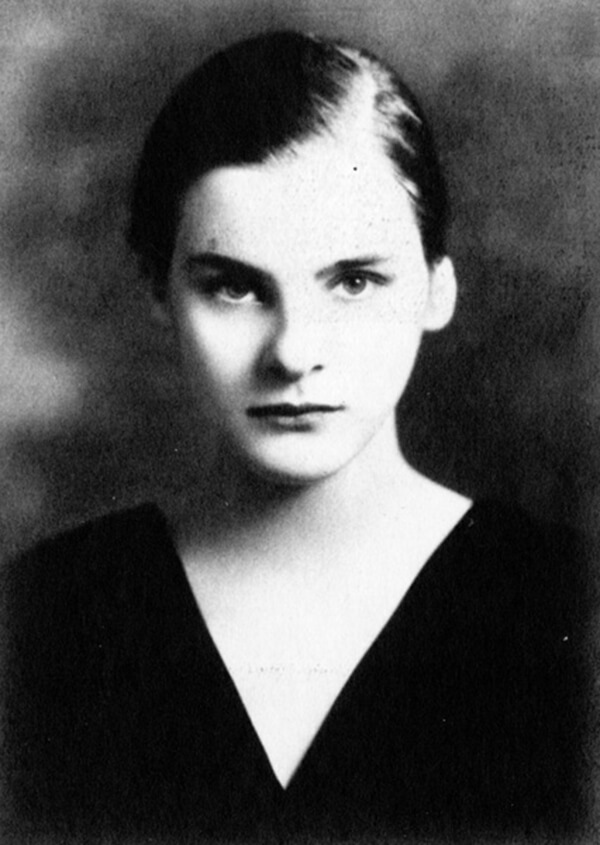

Why was she such a cool, dispassionate observer, so passionately inclined to tell the truth?

It could be because she was an interloper in New York’s highly pedigreed mid-century intellectual world. Orphaned as a small child, she was sent to live with casually cruel and dreary relatives in a lower-middle class suburb of Minneapolis. She was punished for excelling, and her life might have taken a very different turn were she not rescued by her maternal grandparents in Seattle, a successful attorney and his wife who encouraged her and paid for private schools.

From there, she went to Vassar, where she studied everything from Tacitus to what you served as the first dinner course. McCarthy studied constantly throughout her life. Adopted by the elite “Tower Group” in the Vassar dorms, she wanted desperately to pass and studied their behavior avidly… a study that she’d put to further use much later, when she wrote The Group. As an outsider who’d found a way inside, I imagine she was acutely aware of manners, mores, customs, and the disconnect between the ways that people feel and act.

As a narrator, she was unsparingly truthful about her own ambitions and pretensions, ambivalence and confusion. Margaret Sergeant, the character based on her in Company, is a terrible person, manipulating both her lover and her soon-to-be ex-husband into an excruciating three-way meeting to Discuss the Situation over drinks… but then again, the Situation was excruciating, too. Clearly, McCarthy believed that the ruthlessness she used to scrutinized herself could equally applied to everyone around her. She cast a cold eye, as she titled one of her later books. Did she go too far?

Responding to a question about her contemporary Lillian Hellman on The Dick Cavett Show in 1979, McCarthy quipped: “Every word she writes is a lie, including ‘and’ and ‘the.’” It was an opinion most of their contemporaries shared, although none would dare to say it. Hellman’s WWII memoir Pentimento had recently been adapted as Julia, the Oscar-winning film, and she responded with a 2.5-million-dollar libel lawsuit—a suit, she later said, she’d drop in exchange for an apology. But McCarthy, 67 years old, happily married for the fourth and final time, financially comfortable but by no means rich, refused to back down. Only Hellman’s death—and the decision of her heirs to drop the suit—spared McCarthy from financial ruin as she approached her seventies. The writer Elizabeth Hardwick, a lifelong friend and sometimes frenemy of McCarthy’s, described her stubbornness in an essay written after McCarthy’s death:

“If one would sometimes take the liberty of suggesting caution to her, advising prudence or mere practicality, she would look puzzled and answer: But it’s the truth. McCarthy tried to take in all the details of her surroundings and produced work that serves as a document of its time. Reading her collected fiction, we may marvel at how much her cold eye saw—but we may also note the things it missed.”

*

I’m trying to remember when I first became aware of Mary McCarthy’s work. She was a famous writer, famous like Jacqueline Susann, it was impossible not to hear of her. Maybe I saw dog-eared copies of The Group in Bantam Paperback on the beach or my mother’s nightstand or the parent’s bedrooms of friends, but I remember becoming positively aware of her as a writer when I discovered her translation of Simone Weil’s beautiful essay “The Iliad, or The Poem of Force.”

It was the mid-1980s and I was working as an office temp in the Interchurch Building near Columbia University. The job was demeaning and boring. Months turned into years and it seemed like it would go on forever. The center had a library in the basement of mostly religious books, but they had a copy of McCarthy’s translation and essay, published or self-published as a chapbook in 1945. It was one of an edition of 500, and in all those years it had only been checked out once or twice. I found this comforting.

At the time I was working part-time at the St. Mark’s Poetry Project, and this was what poets did—translate other poets who they counted as progenitors, and publish chapbooks of their own work and their friends read by no one except other poets. That glamorous Mary McCarthy, known by then as the “first lady of American letters,” would champion the work of this then-obscure badly dressed forgotten philosopher made her seem a lot cooler. Or rather, sincere in her identity as a writer in ways you wouldn’t expect, given her stature.

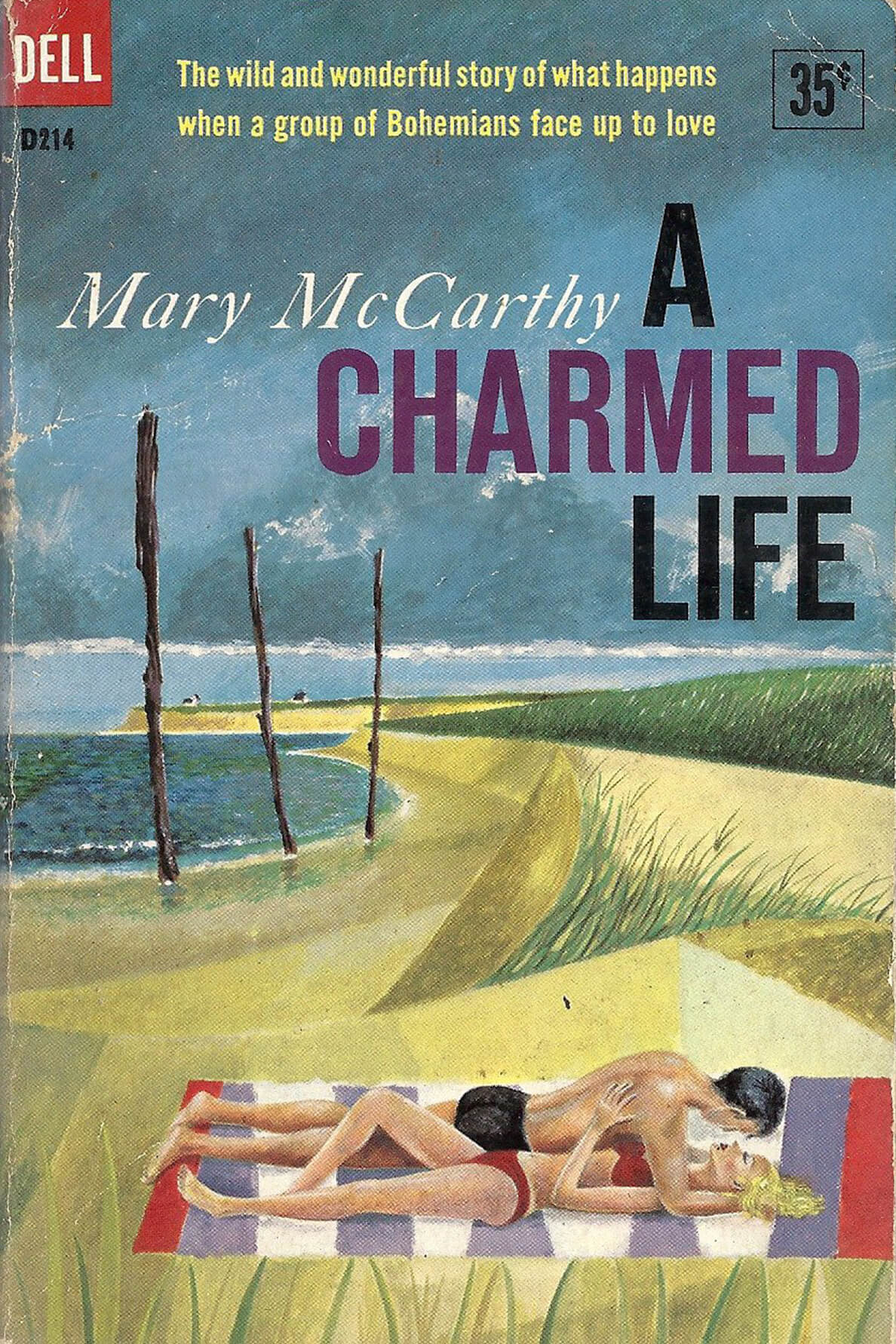

A few years later I discovered her third novel A Charmed Life and read it over and over again. By then I was married and living in Springs, outside of East Hampton—a location we chose because it was much less expensive than a Manhattan apartment. A Charmed Life is set among a group of writers and artists living in New Leeds, Massachusetts for exactly that reason. All of her characters have one foot in New York, but—either psychically or financially—cannot afford a full-time life there. Martha Sinnott, McCarthy’s protagonist, is a former actress reluctantly writing a play that will never be finished. Her husband encourages her to advance her career, although all she really wants is to get pregnant. The novel is full of hilarious set pieces: scenes of provincial life among less than completely successful self-exiled intellectuals. Martha is torn between her current and former husband, who arrives in New Leeds just as she’s agonizing whether to comply with her husband’s desires or get pregnant anyway. But before she can reach any decisions she dies in a car crash, which at the time seemed like the most perfect ending.

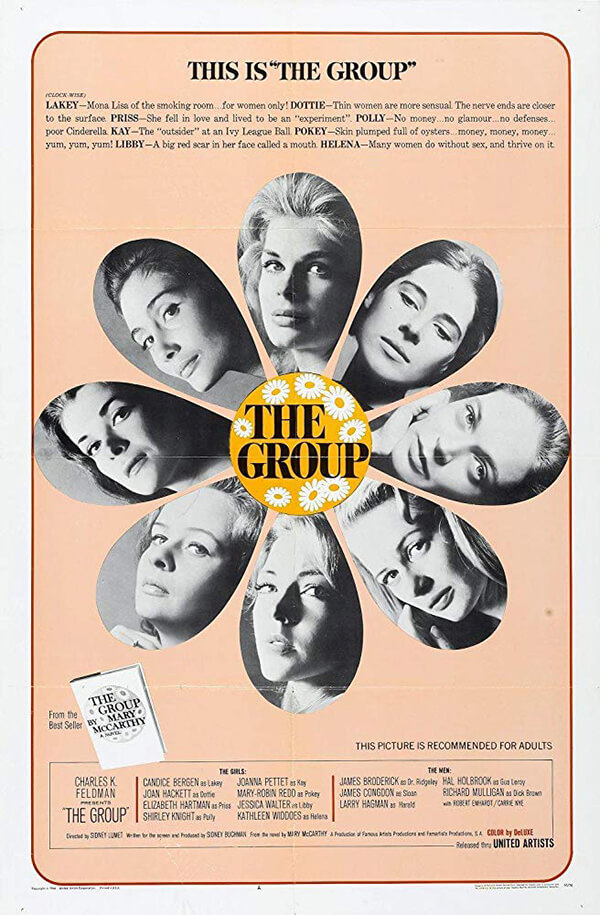

But it was McCarthy’s tenth novel, The Group, that made her famous. It was banned in Australia. She received letters care of her publisher asking, What kind of filthy perverted mind do you have to write such a novel? Even more damning among her old trust-funded friends from the New York Review of Books and the Partisan Review, it was commercially successful. “It was the book that ruined my life,” she remarked many years later in a newspaper interview.

The Group is an episodic account of the lives of eight friends who, like McCarthy, graduated with the Class of 1933 from the elite Vassar College. It was published 30 years later, in 1963. By then the events of the book were historical, but the situation of these eight women, their conflicts and choices, felt completely contemporary. From chapter to chapter, McCarthy adopts the perspective of each of the girls, perfectly capturing their voices and hopes, their gestures and tics, as well as their prejudices. In the opening chapter, a kind of medley, the group gathers for the wedding of one of their number, Kay Strong, to Harald Peterson, the boy she’d been sleeping with throughout college. Harald, a hard drinker, is an aspiring playwright and sometime-stage manager. Five years older than Kaye, he’d attended Reed College, as less-elite west coast institution. Kay, the daughter of a Midwestern doctor, is about to start work as a management trainee at the department store Macy’s. There are no family members, and few other guests, at the wedding. The group are too dogmatically open-minded to be shocked by this situation, but they’re not stupid. Clearly, the marriage is wrong. They valiantly try to dispel the cloud of unease with relentless babbling.

As privileged women coming of age at the start of the Great Depression, the girls in the group want to be everything their mothers were not, and do everything differently. Passionate about social progress, they embark on careers in medicine, art history, social work, management and publishing but they’re defined more by their limits than their ambitions. “The worst fate, they utterly agreed would be to become like Mother and Dad, stuffy and frightened. Not one of them, if she could help it, was going to marry a broker or a banker or a coldfish corporation lawyer, like so many of Mother’s generation. They would rather be wildly poor and live on salmon wiggle than be forced to marry one of those dull purplish young men of their own set, with a seat on the Exchange and bloodshot eyes, interested only in squash and cockfighting and drinking at the Racquet Club with his cronies, Yale or Princeton ’29.”

“The Group was conceived as a kind of mock-chronicle novel,” McCarthy later explained in an interview. “It’s a novel about the idea of progress, really. The idea of progress seen in the feminine sphere. You know—home economics, architecture, domestic technology, contraception, childrearing; the study of technology in the home, in the playpen, in the bed. It’s supposed to be the history of the loss of faith in progress, in the idea of progress during that period.”

The book topped the Times bestseller list within weeks of its pub date, and remained there for months. Film rights had been sold, and everyone had an opinion about it. Her depiction of the aspirations and friendships of these eight Vassar girls determined to make their own lives as different as possible from those of their mothers spoke powerfully to readers of the early ‘60s. Except for the mysterious Elinor Eastlake who escapes the US for Europe and a lesbian relationship, the girls stumble over the conflicting mores of their generation’s sexual liberation. Navigating the unbridled cruelty of their employers, husbands and boyfriends, their failure is a foregone conclusion. Part of their minds are still in class at Vassar debating ideals as they agonize over affairs, lunch menus, and contraception. Just as she did in The Company She Keeps, McCarthy treats sex as a subject for comedy, and there’s a lot of sex in this book. Never before had a mass-market readership been exposed to such an audacious American comedy of sexual manners—even more shocking because the author was female.

The book was attacked in the New York Review of Books—a publication she helped to found, and frequently wrote for—by Norman Mailer. In a 4000-word attack in his hyperbolic style, Mailer depicted The Group as “a trivial lady writer’s novel,” infused with “a communal odor that’s a cross between Ma Griffe perfume and contraceptive jelly.” Appointing himself the defender of masculinist proletarian literature, he is repelled by “the profound materiality of women … given its full stop until the Eggs Benedict and the dress with the white fichu, the pessary and the whatnot, sit on the lone of the narrative like commas and periods … Mary is a bit of a duncey broad herself.”

Mailer’s attack was an inside job arranged by their mutual friend Robert Lowell. The insult was made even harsher by the fact that Lowell’s wife, and McCarthy’s good friend Elizabeth Hardwick, had published a mean-spirited parody in the New York Review under a pseudonym a few weeks before that. These were her friends.

McCarthy was living in Paris by 1963, but she returned to the US to do promotional readings and interviews, well aware of the chilly reception she might receive from friends—but not the public. On a brisk November Sunday, she took the stage of the 92nd Y in New York to thunderous applause. Fifty-one years old, she was at the top of her game, wearing an elegant white dress and small jewelry. The night before, she’d fled a party at Dwight and Gloria MacDonald’s apartment in tears at two in the morning because Fred Dupee, a now-completely obscure critic and scholar told her how much he’d disliked the novel. He wasn’t the first or the worst, but he was the first to say it directly. About fifteen minutes into the 92nd Street reading, McCarthy paused to explain what her strategies were for writing the novel. She mentions her use of indirect free speech, the same device used by Flaubert in Madame Bovary, whose gift for harsh pathos she shares. McCarthy explains: “the voice of the author is heard, but very rarely, and quickly lost. All through the book, when a girl is thinking about her own life or telling her own story . . . the tone of the chapter is as if she were telling to story to a group of friends.”

“Everything,” she explains, “in the girls’ lives tends to be technologized—the breast feeding and contraception problems—that is technologized, and in some ways socialized and alienated in some way. Everything that happens to these girls is turned into a subject for group conversation. What I’m trying to do in this book is to make some kind of study of what it meant to be young, for one thing, and what it meant to be a young American trained in progressive ideas, and trained to be a consumer…. I hope that I made myself clear. I thought I made myself clear when I was writing it, but it appears that I hadn’t.”

And from there on, she relaxes. When she reaches the passage about the domestically slovenly staunch communist Norine going to Bloomingdale’s to buy black chiffon underwear to turn on her impotent husband—“that should get his pecker up”—she puts her hand on her hip, and the audience roars.