Between Two Documentas

Hunter Braithwaite

August 14, 2017

I first went to Kassel to look at Documenta in the summer of 2012. I went a second time five years later. After that first trip, I jotted the word wiedergänger in my notebook. Someone who comes back. It refers specifically to a folk creature who comes back from the dead, but I meant it in a more general sense of return.

In 2012, Documenta 13 had crested on a swell of historic optimism, and had been so curatorially open-ended—expanding the realm of art beyond the limits of experience or understanding—that it prompted in me an inchoate yet urgent desire to return as soon as possible, at least to see what else art could do. Because art, I had been made to feel, could do anything. We have since seen that one thing it cannot do is stop the global slide towards nationalism and oppression.

This societal regression formed the foundation of Documenta 14’s landmark work, the Argentine artist Marta Minujín’s “Parthenon of Books,” (1983-2017) which recreates the classical structure out of 100,000 books that have been banned at one point or another. The building is located in Friedrichsplatz, one of the many locations where Nazis burned books. In both photographs and in actuality, the Parthenon looked like a rendering. In the former, it looked unreal, a hypothetical model sited in a stately European square; in the latter, up close, surrounded by copies of Animal Farm and Justine protruding from the flimsy plastic structure, it was rendering-as-melting-down, the destruction of the global body politic—an apt monument for an age of ecological and social breakdown.

Besides welcoming Documenta-goers to Kassel, Minujín’s Parthenon let them know that a little over 1000 miles away there was Athens, home to the actual Parthenon, as well as half of Documenta 14. That’s where this Documenta began for me, sitting just outside the shadows of the saran-wrapped colonnade, having an espresso and wishing instead that I ordered a sausage.

When I was finished, I walked up to the Fridericianum. This building was the center of the previous Documenta, site of revelation after revelation. Upon entering it five years ago, I had felt nothing at first but cold air. It was Ryan Gander’s brilliant ventilation hack—an interior wind—that led me into a gallery with Kai Althoff’s letter of resignation, and Ceal Floyer’s “‘Til I Get it Right,” a looped section of a Tammy Wynette song. I still remember the feeling of emptiness, of potential—a poignant absence that was, five years later, muscled out of the way by hot and dusty art objects.

The organizers had brought the collection National Museum of Contemporary Arts, Athens (EMST) to the Fridericianum—replacing the center with the outskirt to visualize ideas of cultural transmission and centrality. Funny how the center shifts though. Athens, of course, is the cradle of Western Civilization. Meanwhile, Kassel—Documenta’s home base, having hosted the event since 1955—was chosen because it was on the border of East and West Germany. Central to the Cold War, but liminal in an ideological sense. It was an interesting gesture. Unfortunately, gallery after gallery revealed boring, ersatz formalism that only underscored just how much art is made and exhibited around the world, and how rare it is to see something truly noteworthy.

I left the Fridericianum feeling quite depressed and walked back to the hotel, buying a hot and dusty bottle of wine on the way. The hotel was around the corner from the train station. Dark and empty, the interior felt like a wax museum. The room was huge, with a double-sized, half-lit bathroom. I’d accidentally reserved a smoking room—there were ashtrays and cigarette burns on the furniture, though, since no one had stayed there in recent memory, it didn’t actually smell.

*

At Documenta Halle, a crescent-shaped building on the edge of the old town, above the Orangerie, the gardens, and the verdant expanse of the Karlsaue Park, the galleries nearest the entrance had to do with sound. An installation by Igo Diarra and La Medina presented records and costumes of the Malian musician Ali Farka Toure. Here was a feeling that I often hope to have in exhibitions: the desire to know more. Sure, they piped in some of his music, but the gallery was too loud to hear it clearly, what with the churn of school groups and the acoustics of the place being frankly miserable, and it was also too hot to hear it.

In Copenhagen and Berlin it had been too cold and now it was too hot. Unless you were in the shade. Then it was too cold. It was also simultaneously too dusty and too humid. In these frustrated binaries—neither one or the other, but somehow both—was the meteorological equivalent of an art show that took place half in Germany and half in Greece.

As if responding to a larger, unheard sound elsewhere, a suite of works by sound artist Alvin Lucier rattled on a nearby wall. The pieces were quite simple: a framed piece of paper with a small speaker connected to the back. When a sound passed through the speaker, it was amplified by the vibrating paper. These vibrations gave off noise, which was what he wanted, and also a slight breeze, which is what I wanted.

Then came Stanley Whitney; one of my favorite painters, he was also one of the few artists in the show whose work I’d seen before. And here he was, all turpentine hustle, chromatic syncopation. All of the paintings were from 2017. One of Whitney’s many charms is how his paintings bring out a childlike quality in the viewer. I mean that every time you see them is the first time, anew. They are atemporal, standing outside of their own viewing history. Not to be remembered, they resist being re-seen. The splashes of color, futilely segregated by the blocky regimentation of the composition, are arrested mid-swish.

The paintings manage to be both tranquil and fevered at the same time, and were thus reminiscent of Etel Adnan’s paintings, which were on display in the Halle during the last Documenta. With simple compositions of audacious color, often applied with a palette knife, the Lebanese-American poet and painter elevates the mountain or coastal landscape to the idealized heights of formalism. They do not directly refer to the devastation of her native Beirut, just as Whitney’s don’t refer to the social upheaval of Trump’s America. But in their refusal, we have transcendence.

Though I only spent a few minutes in the gallery, time folded down into an asterisk, something to be revisited, expanded in a footnote. That’s often how it happens. You touch down, collect the luggage you wanted to carry on but had to check at the gate, take the bus to the train station and then a train to the tram station and then a tram to a hotel, and you try to check in but your room isn’t ready because it’s Berlin Fashion Week, so they give you a drink ticket for your trouble and you head to the roof for a cocktail, something refreshing, something with a slice of cucumber on the rim, only to find on the roof the same café you’d found in Miami, in Istanbul, with the same salt shakers and the same grilled octopus and sunchoke puree, distinct only because the looming TV Tower gives it a certain end-of-history vibe (unlike, say, in Miami, where the vibe is more end-of-the-world), but you wait there and take notes, and later you take the train to Kassel, and you get there hungry, and wander around looking for something you wanted to see, that you were supposed to see, until finally you find the gallery you were looking for, the one you will remember, and spend, oh, five minutes there before decamping for a beer.

*

The next morning I walked the gravel path overlooking Karlsaue Park and felt hot in the sun. Having not finished my coffee by time I arrived at the Neue Galerie, I continued across a footbridge and up into the Grimmwelt Kassel. There, in a museum dedicated to the Brothers Grimm, Kassel’s best-known cultural exports, were other fables of language and loss.

First was a series of plaster panels, scenes from Grimm stories, chipped and faded and decorated with animals and fairytale figures. They were painted by the Jewish artist and writer Bruno Schulz to decorate a nursery with. The nursery, however, wasn’t his. It was located in the Villa Landau, the home of SS officer Felix Landau, who commissioned Schulz and protected him until Landau was murdered by another SS officer for shooting his dentist. “You killed my Jew. Now I’ve killed yours,” the murdering officer said. Seen here, devoid of their surrounding domestic architecture, the panels could easily be illustrations pulled from a fairy tale of the twentieth century, an absurd story that we thought we left behind.

In a darkened room beyond, Susan Hiller’s 2016 film “Lost and Found” brought together field recordings of dead and dying languages, from the American West to Isle of Man to New Zealand. These were stitched together via a simple visualization, a wobbling sound wave projected on a black screen. And indeed, the languages returned to their natural medium—sound. The gurgles and clicks, sonorous stutters and leaps, repetitions, emphases. Oral bursts that no longer make words, and, like the extinct Bo language of the Andaman Islands, probably never will again. These languages didn’t die out on their own; they were, without exception, doomed by imperial intervention, or by domestic policy.

The Neue Galerie was the most cohesive space that I saw. I didn’t see everything in Kassel, and even if I had, I would only have seen half of Documenta 14, so in this way the incompleteness of the experience was completely intended—was complete. And besides, even if you’d seen everything, you still couldn’t experience the entire piece. In the nearby Neue Neue Galerie, a vacant mail distribution center that I had stumbled through on my first day there, videos by Forensic Architecture about the NSU assassinations of Turkish immigrants were urgent, essential, and, due to the spatial and temporal constraints of being in an art show held in a repurposed post office, impossible to appreciate as an art piece. Journalism, however, is another story entirely.

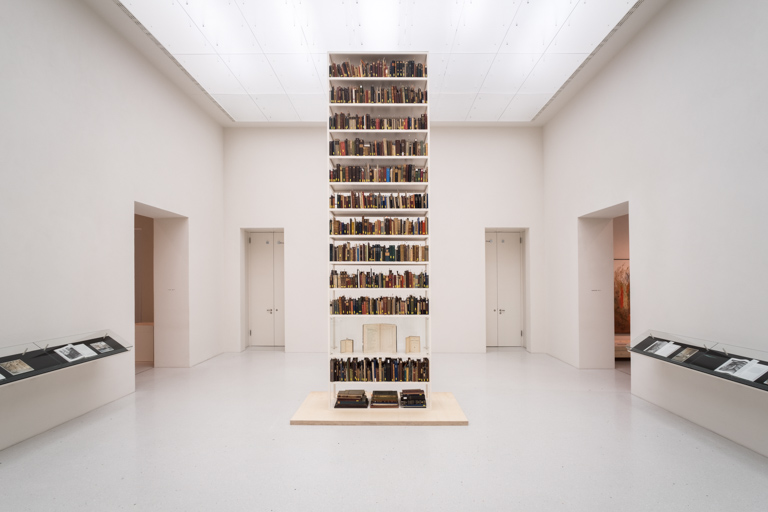

A similar piece at the Neue Galerie was Maria Eichhorn’s journalistic deep dive into the Nazi confiscation of art leading up to and during World War II, especially in Paris. Through extensive research, she follows the money, and the art, through the decades, revealing a system of complicity and willful shirking of responsibility on the part of the financiers and architects of the art world, and, by extension, its laypeople, the exhibition-goers. Laid out in vitrines, a 720-minute-long video of auction records, a towering shelf of books, and a bilingual library you could peruse, the piece is daunting, and yet a necessary example of how the resources and audience provided to a Documenta artist (or one at a biennial, for that matter) can move the common good a peg or two forward.

Elsewhere, connections were forged between different places and moments in history, suggesting the ability of art to, if not repair today’s fractured terrain, at least gesture towards empathy and understanding. Take Yves Laloy’s triangulated “Le Grain Approche,” a work that Breton considered surrealist, but which the artist likened instead to Navajo sand painting. Laloy’s work was displayed alongside Marilou Schultz, a Navajo weaver whom Intel commissioned to weave a replica of a computer chip. Navajo women were the primary laborers at computer circuitry factories in the American West during the 1970s. Another vitrine tells the story of the Fairchild Industries factory in Shiprock, New Mexico, which was taken over by the Native American activist group American Indian Movement in 1975. Thus, one gallery condensed the subconscious, the indigenous, and the technological. The next gallery, with Vija Celmins paintings of stars, reduced it all even further, to pinpricks of hope in the void.

*

.jpg)

The spacing of Documentas at half-decade increments foreshortens historic time to match personal time. At a vantage of five years, we are aware both of how it felt then, and everything that’s changed since. This loping regularity gives events like Documenta their historic heft. Like eclipses or elections, or the cycle of decades in our own lives, we measure ourselves against them. And the world as well.

In John Berger’s “Between Two Colmars,” an essay I’ve returned to again and again, and from which I’ve appropriated the first two sentences of this essay, the writer visits Grünewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece in 1963 and again in 1973—five years before the events of 1968, and five years after. He compares the experiences of viewing the work during a “time of expectant hopes,” and a time when those hopes had been “categorically defeated.” The essay is golden, like much of his writing; a guide to weaving one’s own life into the textiles of our larger histories. He ends with this remarkable sentence:

In a period of revolutionary expectation, I saw a work of art which had survived as evidence of the past’s despair; in a period which has to be endured, I see the same work miraculously offering a narrow pass across despair.

Berger’s reading of the altarpiece and the work itself are both embedded in history—be it personal or societal. So too is Documenta. And while the previous one was invigorating and exploratory, this year’s, devoid of speculation, turned inward and back on itself, embattled yet still breathing, has much to tell us about navigating the pass across despair.

*

Out front of the Hauptbanhof a shipping container hides a passage underground. You walk down into the cavernous underground train station which, judging by the posters still affixed to the tiled walls, had been out of use for over a decade. The subterranean exhibition hall was the ideal venue for a Documenta, and a world, wracked by violence and fear. In a darkened tunnel we approached Michel Auder’s video installation: fourteen blinking screens showing a detail of Gentileschi’s “Judith Slaying Holofernes” (1614-1618), images of natural disasters, gutted fish, iPhone screenshots of Facebook feeds, and photographs of Donald Trump.

If there was ever a time to be endured in my lifetime, it is this. Yet, a path. We walked along the abandoned tracks, the gravel crunching underfoot in a fairly mythic way—as it would on a path at Stonehenge, or up to a volcano. At the end of the tunnel was daylight. We followed a group of people towards it, and then others picked up behind us. When we reached the end of the tunnel, we were greeted with a sign that read, in Greek, Hello!