To Burn Again

Rebecca Bengal

July 31, 2017

The fire started in Brandi Twilley’s bedroom. No one was home, except the cats. Maybe one of them had knocked something onto the ancient space heater with the missing ceramic plates and it sparked, lit. This had happened before. Black patches permanently inked into the floor marked the spots where it had burned, been put out, no big deal.

Uncontrolled this time, though, the fire spread, lashing through the house to the other bedroom, to the living room, where the already flagging roof gave way completely. The fire burned photographs, furniture, clothes; it burned all of sixteen-year-old Twilley’s paintings, the charcoal drawings she’d made of her brothers and sisters. It burned her little brothers’ brand-new Christmas presents. This was Oklahoma; January, 1999.

Brandi Twilley’s paintings of her childhood home before and during the fire that destroyed it were first exhibited last summer in her show The Living Room, at Sargent’s Daughters. She painted the wet stains in the ceiling and the walls warped by the water that had begun to seep through the roof in the house’s final years. She painted a bed on fire, golden flames rising out of a mattress; she painted the Christmas tree with its colored lights making a little decorative glow around a littered room; in another painting, she pulled back to show the beds or couches and the trash cans and buckets to collect rainwater and a slice of afternoon sky visible over the top of a boarded-up window. That same room, at night, cast in the television blue of evening with two TV sets side by side, tuned to different scenes, drawers left open, scattered videotapes and Nintendo consoles and soft drink cans and cups with straws sticking out, Barbie dolls in repose on piles of clothes.

-Web.jpg)

The ten paintings in The Living Room were all unpeopled interiors of the house, before and during the fire, at different times of day, different seasons of the year. In “Fall Painting,” the season matches the art on the wood-paneled walls, a work purchased at a flea market. In “Fire and Fall Painting,” more flames burst out of a bed, rushing dramatically toward the painting, with its burnt autumn hues, its placid creek.

Last summer, walking through the gallery, I felt oddly at home in the world of Twilley’s pre-fire paintings, the near-breathing presence of the house, the unapologetic disarray that was jarring but also reassuring in its realness, in its loving anarchy, as the unseen household relaxed its grip on civilization, the house itself sliding slowly into wilderness. But “Fire and Fall Painting” also triggered in me a shock of familiarity that would be weird and wrong to ignore. The painting within Twilley’s painting, on the wood-paneled living room wall, was a near match for the woodsy creek painting on the wood-paneled living room wall of my grandparents’ farmhouse in North Carolina, one of a handful of reproductions they had purchased from the Sears catalog with insurance money after fire destroyed their own home.

All this had happened before I was born, yet it is an event that has nonetheless hovered over my own life and writing. It is an innocuous painting, too, but I stared at it so much as a child that I practically dreamed my way inside it. As I’ve grown up, I’ve watched it fade and pale under years of bright afternoons behind sheer curtains. Looking at an image of “Fire and Fall Painting” now, while Twilley’s new exhibition Where the Fire Started, hangs on the walls of Sargent’s Daughters (on view through August 18), what strikes me is that the fall painting is the last thing intact in the room, the last thing the fire takes. It points toward the dozen paintings in the new show, which depict fire, but which even more prominently also feature paintings-within-paintings, by Twilley or other artists. It frees the paintings of Where the Fire Started, dark and transformative and dangerous, to be as much about art as they are about violence, about the way that destruction and death give way to creation, about how we tell ourselves stories in order to let go.

*

After the fire, Twilley and her family never saw the cats again. The missing animals, and the art she made for years, were the toughest losses to bear. The first time they drove by, after, the only house she’d ever lived in was “just this big black skeleton,” she tells me, when we meet near her studio in Brooklyn. “Nothing survived, but you could go to the fridge and open the door and there was stuff in there.” In that first year, she began making paintings and drawings of the house, while her memory was fresh and raw. Years would pass before she would return to them again.

She didn’t paint the house during her years at Yale, where she received her MFA in painting, but after, alone. Reconstructing from memory, from dreams, from those first-year-after drawings, from a couple Polaroids at her grandmother’s, from a photograph of the house as it burned. She Google-imaged the items of a ‘90s childhood, a Trapper Keeper notebook, a Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtle sleeping bag. In Where the Fire Started, she resurrects her favorite painting lost in the fire, a piece inspired by a dream she had about plane crash survivors. They stand in the water, fishing out peoples’ limbs.

She collected images of actual fire, too; she was partial to the paintings of Hieronymous Bosch. When Bosch was in his teens, fire devastated thousands of houses in his Dutch hometown, ’s-Hertogenbosch, most likely also including the house where he lived. For Twilley, painting the fires was a release, a studio reward. “I would love to have an excuse to paint ten more of those blackened slabs,” she says.

In Where the Fire Started, though layers of atmospheric smoke swirl in some of the rooms, she granted herself only one true full-on fire painting, whipping out of the front windows of the house, a hot billowing blaze and a screen of smoke against a blue sky, terrifying and magnificent and textural. “Technically it’s very easy to paint but I thought a lot about how a fire should be painted and what it is,” Twilley told me. “It’s very liquid and thin and it’s always moving, it’s never stiff, so it should be painted very fluidly.” Nothing is ever truly still in her paintings. Even the inanimate objects feel touched with inner motion, a shapeshifting presence.

She plotted the sequence of works like a storyboard, allowing a narrative arc to control the direction where memory gapped. She holds the paintings accountable to a level of emotional truth without belaboring details—Simpsons graffiti that she could have drawn on the bar of a bed frame at the time, the shows they might have been watching, but no invented architectural forms, and only cats who actually lived in the house.

Some of the cats had been family pets, adopted and fed and cared for. Some simply announced themselves, the way strays do, taking up residence in the house’s hidden corners. Perhaps the arrival of the cats signaled to the humans what they had not yet let themselves fully acknowledge: that the distinction between spaces for living, eating, sleeping had been erased; that the border between the house and the outdoors had begun to recede. At one point, Twilley says, she drew the mushrooms that had begun to grow on the carpet. Last year, when the cats showed up again—this time, in her paintings—she decided to let them stay.

In the paintings that make up Where the Fire Started, patches of sky are visible through the exposed roof; rain falls onto the floor. A bright blue camping tarp, a shield against those indoor showers, shrouds the bed in the foreground where Twilley slept. A bedsheet is pinned up in a window; Twilley’s drawings are tacked up on sheets of plywood. This is a bedroom, but it is fast on its way to becoming an artist’s studio, accumulating scattered papers, brushes, folders of more drawings. It is a room, too, in a state of palpable metamorphosis. Even the walls, warped with moisture, appear to be in motion. Outside, a wooded blue-tinged world is faintly visible, fantastic and magical but truly just an Oklahoma backyard.

In the midst of the scene, in the gloam hour of this room, a black cat sits in an office chair, gazing in the direction of that blue beyond. If this were a movie, the roof would yawn open and snow would fall in. Push against a wall, you imagine, and you might hit the cold woods outside, like the wardrobe entrance to Narnia—a journey which, like most fairy tales, is piloted by children, helped by animals, and ultimately about the quest for transformation and for home. Twilley captures the moment at which the house becomes a character, taking on a life of its own, and preparing to step into its own afterlife.

Something happened to the stray cats sleeping in the attic eaves. They got sick, or hurt, or both; they didn’t make it. In “Cat in the Roof,” the white-hot glow of the heater makes a filmy halo, showing up the elongated strips of blood and maggots that rained down the walls. “Eventually we washed them off,” Twilley told me, though traces must have remained. Shadows fall across the room, the grayness mixing with the smudge on the door, residue of smoke, of the greasy marks of six children. Another cat, the color of darkness, curls up at one end of a sheetless bed. Emotionally, Twilley said, it was the most difficult painting to make: “I wanted to honor that cat’s life.” It took her three months to complete. She made her first attempt while still in school, long before the land where her house once stood was paved over, a supermarket constructed in its place. No one in her class asked, then, about the streaks of blood.

The friend who told me to go see The Living Room last summer could not have known how deeply the work would hit, the kinship I would feel both with the world of the paintings, as someone also from a place so often misunderstood, misrepresented, and gothicized, as well as with the task of the artist who presented them, in dual conversation with her teenage self and her imagination. Here was a complicated, honest reckoning of traumatic loss and coming of age that resisted defense or easy explanations.

The threat of fire hovered over my childhood. One morning I woke to discover the house across the street from mine burned overnight, the family suddenly homeless. The year before, a great uncle, who I knew as an eccentric mountain man with whom I shared a middle and a last name, had perished in his cabin. The flames were already so high that his brother, my grandfather—just down the road in the house built in place the one he’d lost—could not reach him in time.

Two houses, burned a dozen years and less than a hundred yards apart. They exist for me only in the remnants of its surviving sister barns and sheds elsewhere on the farm, in the few home movies and photographs that were rescued, in the litany of family histories retold. Did the stories unspoken, then, belong to the people they’d died with, or did they somehow belong to those of us who came after? I looked on the gravestones with the names rubbed off, to the significant bottles buried in the banks of the dirt road, in spots in the pasture and in the woods, where lone chimneys marked more vanished buildings. A while ago I learned to quit asking so many questions. I’d fill in those missing structures myself.

In the driveway of the house that replaced the one my grandfather built is the metallic green truck he drove, a vehicle we all prize. It has barely moved in the nearly twenty-five years since he died; my grandmother will not let it out of her sight. Perched over the gas cap a plastic bird keeps watch; me, I just listen. The bed of the truck fills with commonplace things, tools, bags of animal feed. The farm itself is changing. First my grandmother had to let the pigs go, then the chickens, then the cows. In their absence, the grass grows high in the pastures. Feral cats roam unseen. Sometimes they grow tame, show up at the front door.

*

Ashes to freedom. Think of other houses burned. In novels, in ritual, in film, the fire narrative gives way to an escape hatch, however limited. To free themselves from the choke of a small town and its prying, judging eyes, orphaned Ruthie and her transient aunt Sylvie set ablaze Ruthie’s childhood home and make their getaway in Marilynne Robinson’s Housekeeping. Holly Sargis, the affectless baton-twirling South Dakota teenager Sissy Spacek plays in Terrence Malick’s Badlands, is fifteen when her house burns down, a year younger than Brandi Twilley was. Here the similarities end: Holly’s new boyfriend Kit, based on the serial killer Charles Starkweather, played by Martin Sheen, has just gunned down her father; after, he splashes gasoline all over Holly’s childhood living room, strikes a match.

Here the similarities begin again: The burning of the house, set to a passage from Carl Orff’s “Gassenhauer,” is as rapturous and haunting as Twilley’s paintings. The camera lingers especially over Holly’s bedroom, the burning bed, the torched dollhouse, the complete severance from her childhood. Minutes earlier she stalks out carrying a brown leather suitcase and, under one arm, a painting. A print by Maxfield Parrish, whose artwork allegedly was displayed in one out of every four American households at one point in the twentieth century, “Daybreak,” suffused in tones of blue.

Before they hit the road for the next outlaw phase of their lives, Kit drives Holly to the high school to pick up her textbooks, so she won’t fall behind on her studies. The books and the Parrish print, which hangs in the riverside Swiss Family Robinson-style treehouse camp Kit builds in the woods are the only possessions left over from her past life. Eventually, after she watches Kit shoot up half a dozen more victims, Holly will turn herself in, get probation, marry her lawyer’s son. It’s not much of a happy ending but, delivered in her flat, plainspoken speech, she reclaims the story for her own.

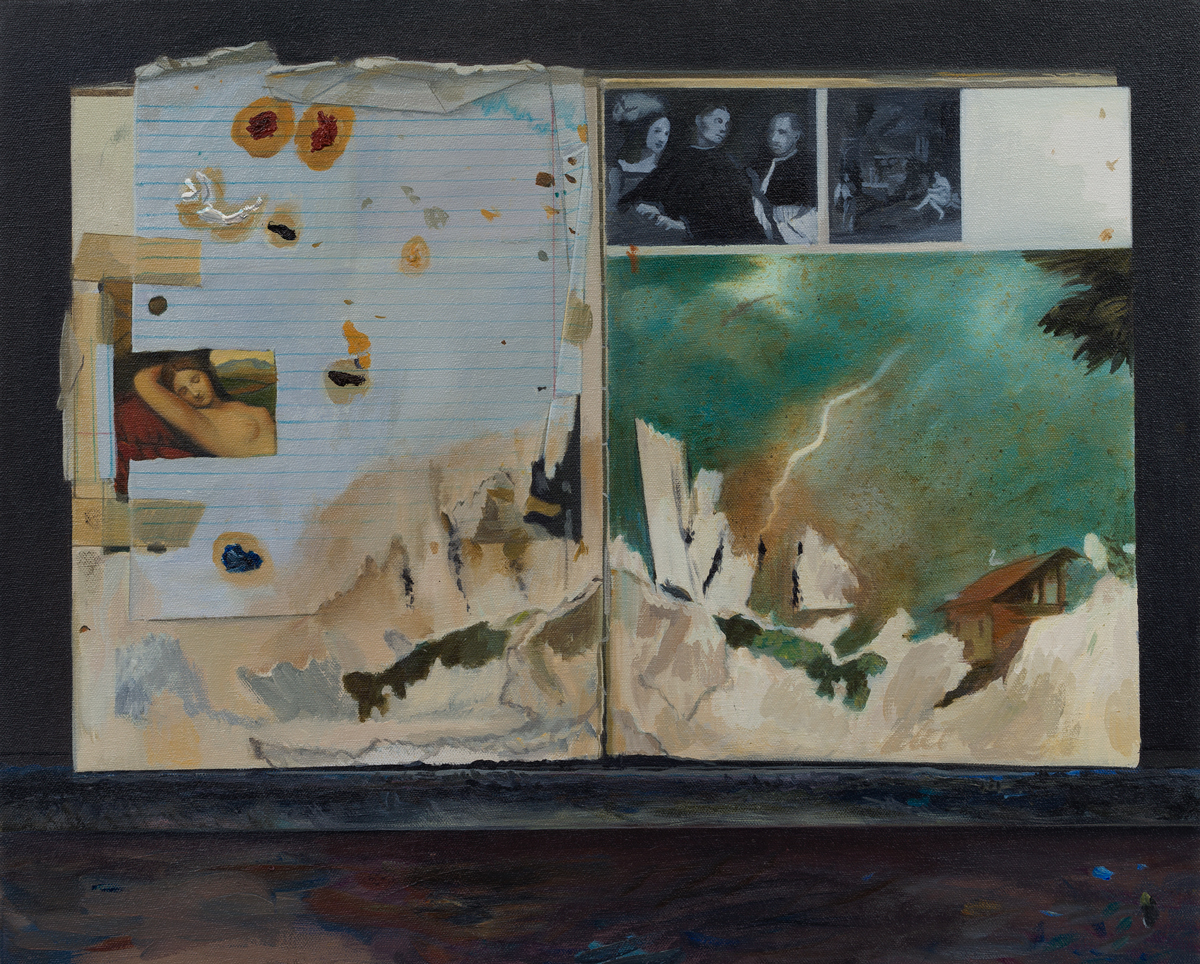

To leave the burned house behind, Brandi Twilley had to build and destroy it again. In January 1999, she was at school with only the clothes on her back and a couple of library books on Titian and Picasso, which she never had to return. They remain among her chief influences—Titian’s glazed surfaces and Picasso’s blues feature prominently in these paintings—but for years Twilley rarely reopened the actual books.

Last year she began painting the pages themselves, the stained book covers, the images that had imprinted on her teenage brain, smudged with her dirty, paint-daubed fingers, scissoring out parts and taping in it her own drawings. Seen alongside the paintings of the interiors, the twilight bedroom that had become her studio, they are uncommonly affecting, stoic little survivors. They are tangible evidence of the way Twilley inhabited these pages then, physically and mentally dwelling in them, a second house of the imagination. For this is where the fire started. In her hands, they would become kindling.