Dreaming the Back Loop

Stephanie Wakefield

November 6, 2017

1.

Red skies hang over California, floodwaters lap at America’s Gulf Coast, and just about everything else seems to be going down the tubes. As we tip into the Anthropocene’s free fall, who hasn’t wondered if this is the beginning of the end?

Set 30 years after its predecessor, Blade Runner 2049 depicts a future we can really believe in. Ecological collapse has caused widespread famine, the Blackout has wiped away data and thus history, and the only living things are stunted humans, bioengineered replicants, and giant beetle larvae on distant protein farms. Amid the ruins stands the Singularity incarnate: savior-tech-billionaire-freak Wallace, played by Jared Leto, who is based—like the late Tyrell Corporation—in a massive brutalist temple bathed in noir lighting and updated for the era of climate change with the undulating shadows of rippling watery light.

Wallace plays a katechontic role, manufacturing newer, more obedient replicants; controlling the entire food supply; and expanding humanity’s reach to nine planets. Policing the existential line between human and not-so-human is our hero Detective K, played by Ryan Gosling, a dreary wage slave of the LAPD. A blade runner, K is tasked with hunting rogue replicants. The movie’s opening scene shows him on the hunt, reluctantly retiring an old model unit with a powerful secret. K himself poses a threat, and after missions he undergoes a Post-Trauma Baseline Test to detect emotional response and emergent autonomy—cells interlinked within cells interlinked within one stem and dreadfully distinct against the dark, a tall white fountain played.

Only errant memories, his live-in holographic OS girlfriend Joi (Ana de Armas), and Ryan Gosling’s pensiveness seem to indicate his life is anything but meaningless. But when K uncovers a miracle and begins to suspect himself of being a kind of skinjob messiah whose existence could “break the world,” love blossoms and fantasies emerge. K and Joi overcome their given conditions—replicant, limited AI—and by dreaming, exploring, and some added techne, create another reality beyond ruins where colors are richer and beings more defined. But is it all part of the program—Wallace’s designs, false memories, coding? Is it real?

2.

There are many ways you might choose to describe our time (a crisis, the end of civilization) but recently I’ve come to think that we’re living in the Anthropocene’s back loop. Consider the way ecologists view the world. For them, every system—human beings, swamps, forests, and organizations—has an adaptive cycle composed of a front loop of growth and stability, and a back loop of release and reconfiguration. These come and go, and ecologists and resilience advocates often seek ways to keep systems in the stable climax zone, or at least minimize the disruption.

Right now, we’re leaving the front loop of the Anthropocene, the geosocial formation built on the terra firma of modern thought and action as much as the stable, abundant earth systems of the 11,000-year-long Holocene Interglacial period. The washing away of claims to human mastery over the world, the terminal diagnoses of western civilization, and the human and nonhuman transgression of earthly tipping points signal our entrance into the Anthropocene’s back loop. Safe operating space is unraveling as we enter an unknown world of chaotic fragmentation and freefall, but also experimentation and potential.

Unfortunately, much of contemporary politics and culture is dedicated to holding this deluge back, to manning the wall—disciplining the back loop—beating the lesson into our heads that ruins and bare life are our only hope, asserting in perpetuity, “You know there’s nothing else, right?” Infrastructures, design, and actual walls are certainly a part of this, but perhaps most powerful of all are the lessons exercised on our interiors, imaginations, and dreams.

So, was it real?

[Spoiler Alert]

Of course not.

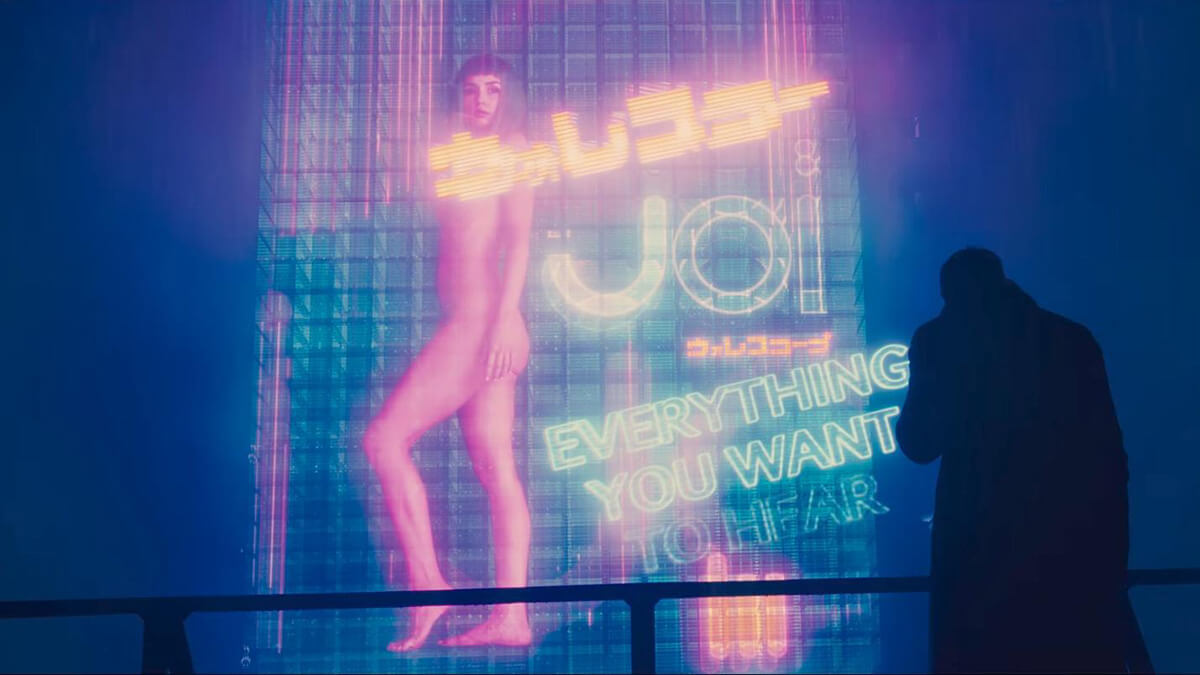

Joi gets free from her mainframe, only to be crushed under the shining boot of Luv, Wallace’s “best” replicant. Far from a miracle or a real someone, K learns he is just a decoy to hide the true messiah. His memories were implanted replications, and alone in the night he encounters a holographic ad for the Joi AITM, who beckons, “you look like a good Joe, let me tell you everything you want to hear.” Joi is a product, an app just doing its job. K and Joi’s love, their meaning, and the possibility of another life beyond 2D ruins woven from the two: none of it was real. Joe—the regular Joe like all of us, working away all our days, feeling lost, wondering if we can get a foothold, maybe daring to dream of becoming someone better, somewhere different—is just a nobody, a naïve skinjob who believes in a phantom love, a tool for the revolutionary replicants, a dog for the LAPD, a foil for humanism.

3.

“Do you dream about being interlinked?

Have they left a place for you where you can dream? Interlinked.”

The baseline check is actually a poem from Nabokov’s Pale Fire, in which a fictional poet, John Shade, has a near-death experience where he sees a white fountain and discovers a newspaper article of a woman who had the same near-death vision. Previously a broken man, discovering this incredible connection gives Shade wonder and purpose. When he tracks the woman down, he finds out it was a typo: she actually saw a mountain, not a fountain. The lesson here? Be more realistic; be more humble; stay servile, K.

In his Western Illusion of Human Nature, anthropologist Marshall Sahlins explains this situation when he clarifies how politics imagines a world split in two: In one sphere is life, and in the other, the forms or answers seen as proper to the government of that life. Such, he argues, is the singular metaphysics across all politics—right, left, or otherwise—and running deep into our own hearts and minds. If the first lesson we’re taught is to not, whatever you do, begin from yourself, and, most importantly, do not trust your real (it’s “just” a dream), then the logical corollary is that the real must come from elsewhere.

Philosopher Giorgio Agamben would want us to understand this as a matter of biopolitics, the way that politics writ large is founded on the splitting of existence into two spheres—on one side bare biological life and on the other life’s forms and modes. Spinoza would say that malicious power always separates the people who are subjected to it from what they can do, forbidding them from effectuating their own powers.

Most powerful perhaps is the Christian dimension to it all. The denigration of self and the profane world was a solution to the endless problem of what to do with those who didn’t want to wait for God to show up again: Essenes, living without property or money in the Judean desert; the desert fathers with their Nitrian gardens who found perfection in solitude; the post-crucifixion primitive church with its agape feasts and image of Jesus not as a martyred or ethereal figure but as a dancing sorcerer, a sun; or the myriad millenarian uprisings in medieval Europe... After all, you can’t have people just going around calling the Kingdom of Heaven into existence! It is to be found in the sky but never here; in the future but never now.

In the more secular present this wall is maintained in diverse ways, yet its impact on our hearts and minds remains just as powerful: What is good or true can only ever be that which is outside of us, appearing to us as a law or form to be applied, or as the awaiting of an event in the future. We live in glitch mode, our beginning and end never quite in sync. We’re taught to live a painful expedition in search of an impossible end, every here-and-now doomed to incompletion and fulfillment. What better way to keep populations under control, lest they rise up against their betters, than by making them sick with self-hate and doubt, resentment and fear?

Consider Kurt Anderson’s recent article in The Atlantic, “How America Lost Its Mind,” deploring post-truth and the invention of new realities by lay Americans:

“Little by little for centuries, then more and more and faster and faster during the past half century, we Americans have given ourselves over to all kinds of magical thinking, anything-goes relativism, and belief in fanciful explanation—small and large fantasies that console or thrill or terrify us. And most of us haven’t realized how far-reaching our strange new normal has become… Much more than the other billion or so people in the developed world, we Americans believe—really believe—in the supernatural and the miraculous…Our drift toward credulity, toward doing our own thing, toward denying facts and having an altogether uncertain grip on reality, has overwhelmed our other exceptional national traits and turned us into a less developed country.”

Anderson calls for the rescue of America from this “fantasy-industrial complex” of conspiracy theorists, UFO believers, ghost hunters, meditators and Foucaultians. To “slow the flood, repair the levees, and maybe stop things from getting any worse,” he calls for “a struggle to make America reality-based again” by reinstating a modern model of expert-driven, rational and unitary truth such as that offered by what we all know to be the bedrock of truth, the national news media.

One need only consider cable news reporters’ Trump-like admonitions of anyone who dared set foot outside prior to, during, or after Hurricane Irma: “Serious risks!” “Not smart!” “Flying debris!” “SUV rolls into Brickell, and the passenger has a helmet on! Thinks they are some kind of storm chaser!” The content of dreams can be dangerous and in need of disciplining. Best to chuckle and flatter themselves with the notion that our undesirable ways of living or dreaming are nonsensical.

“Sadness,” Deleuze wrote, “is linked to priests, to tyrants, to judges, and these are perpetually the people who separate their subjects from what they are capable of, who forbid any enacting of capacities.” In Blade Runner 2049’s final scene [huge spoiler], as snow or soot or ash falls around him, K lays down to die.

“It’s okay to dream a little isn’t it?” Joi mused just before they passed over LA’s massive sea wall, but K knew the truth, “Not if you’re us.”

I was recently in line at Whole Foods, trying to take advantage of those Bezos price cuts, when I picked up Women’s Health magazine. In it, a writer clarified that self-doubt is not actually a lack of trust in ourselves. Rather it is a total trust in both our own worthlessness and in an outside power, an undesirable or unpreferred reality which acts as an impediment to us getting a grasp on our own thinking and living. Women’s Health might be on to something.

4.

For many, the Anthropocene represents the enlightened recognition of humanity as a sickness, a hubristic cancer on the earth, a failed experiment that would be better sent into the night. Christian self-hatred transmuted to a species scale for the age of climate change reaches a delirious, nihilistic crescendo. We will watch with perverse pleasure—not dissimilar from the perverse pleasure left and right take in each other’s failures—as humans fade into the background, machines and plants now deemed the rightful inheritors of the earth. Gardens of erotic statues and huge broken human faces will litter earth’s not-so-distant future crust, future fossils that, like the Onkalo radioactive waste repository, will offer evidence of a human species driven to greedy excess, an Ozymandian cautionary tale for the unexpected survivor to find their remains.

The game, then, will end like this: The water rises around us. We remain mired in debt and fear. Many succumb to pressure or despair, drugs or suicide. Outside the green zones of Wallace Corporation headquarters, the masses slog through the churning wreckage of the 20th century, hocking its jetsam in black market stalls, nodding off against the wall of cracked-out projects, soliciting sex and coke, with the only conceivable heroism that of renouncing our dreams and dying alone at the footsteps of a company lab in the falling snow or soot or ash. At best we can toast one another to a Sinatra song like K and Deckard:

We're drinking my friend

To the end of a brief episode

So make it one for my baby

And one more for the road.

Life passes by. Miracles are impossible. That’s how it always ends anyway, right? “And only a few encounters were like signals emanating from a more intense life, a life that has not really been found. What cannot be forgotten reappears in dreams…These dreams are flashes from the unresolved past, flashes that illuminate moments previously lived in confusion and doubt. They provide a blunt revelation of our unfulfilled needs,” said Guy Debord, who shot himself through the heart.

5.

It’s November, 2017. Here we are. The ground underneath our feet is shifting; the future once imagined, now unknown. But as the Stoics said, it’s really a matter of perspective. You have a choice: see this as a painful loss and look back with nostalgia, suffering a deficient present to be managed senselessly and in perpetuity. Or, see it as the occasion for things to get interesting, to begin again. Grasping for the safe operating space of the past might be more comfortable, but I did like what Edward Snowden recently tweeted from exile: don’t stay safe, stay free.

The test we face is can we stay here, on the brink? Can we inhabit this rift, shape it so that new lands may form? For many it’s the end, and no other way of life is imaginable. Blade Runner 2049 certainly delivers this lesson, but it’s repeated in many voices, high and low (the basic training we receive at any Regal Cinema or Barnes & Noble constitutes the new sentimental education by which we are taught the behaviors and rhythms of Anthropocene life: catastrophe and survival amid interlinked ruins).

The ancient Greeks accorded great importance to their dreams, seeing them as an oracle that accompanied you across place and time—“a tireless and silent adviser,” wrote Synesius. The gods spoke through dreams. But for us living in the undoubtedly messianic time of the Anthropocene, dreams may have a different and more important significance.

We live now in an unsafe operating space, not only because we have already passed so many planetary boundaries, but also because there are no guidebooks, no answers from on high, no guarantees and no assurances. In a back loop the only way forward is to create our own experiments, grounds, and answers—a process that can only begin from the real.

What if the most demanding of our attention appears first in what seems nonsensical or absurd—that is, in the realm of dreams? What if Joi and K already have what they need, the answers to the questions they are asking, within the strangeness of their dreams and themselves? What happens if we have the courage to turn and face this? Maybe it can release us to become something of our own creation, to dominate the chaotic events that inundate us, instead of being dominated by them.

It seems to me that the future belongs not to those who seek to govern or suffer the back loop, but to those who know what they love, and take that love as a starting point and new definition of security. What we love has nothing to do with a set of external properties, biological or otherwise, rather it is an affirmation of what we live and feel, long for and dream—the physical ground we can stand on, and use to construct dwellings small and vast; new mountains towering into the sky. Or maybe it’s a fountain?

“Have you seen the Trevi fountain in Rome? Fountain. Have you ever seen the fountain in Lincoln Center? Fountain. Have you seen fountains out in the wild? Fountain. What's it like when you have an orgasm? Fountain.”

Instead of more interlinking—ubiquitously championed as the only respectable reality—could it be that what we need is de-linking? Isn’t that what K really dreams of? Choice: Live entangled in ruins, surviving a careening landscape of dust and waste. Or let go, detach from these knots and turn within.

“And dreadfully distinct. Against the dark. A tall white fountain played.”

Maybe the back loop is a blossoming idiorrhythmy of diverse and singular realities, and the arts of distance between them.

Society disdains Joi and K, and movie critics mock their delusions, but to each other they are real. While all the other characters behave with resentment and fear, they follow a love for what they have seen and lived. They begin to believe in their reality and give it shape. K gives Joi an emanator, a device that allows her to become physically mobile, untethered from the apartment where she’d been imprisoned until then. “You can go wherever you want!” She takes pleasure in the rain on her flickering digital skin. In one of the film’s most moving scenes, Joi is amazed to see the city and sea wall from the windshield of K’s car. Instead of accepting that she’s only a program, Joi hires a prostitute so she can sync with her and make love with K. “I want to be real for you,” she says to him. K: “You are real for me.”

Finally knowing the risks—she will die if it breaks—she asks K to help her de-link from the apartment mainframe, to become mortal by existing only on the emanator. Maybe K wasn’t desperate at all. Maybe he believed in his value and force, and for a moment explored his potential. Joi and K show the possibilities that would be present if we would allow ourselves to trust what we feel to be real. A threesome with a hologram. An adventure beyond the wall and mainframe. Dreaming for anything but a normal day. K asks Deckard if his whiskey-drinking dog is real. “I don’t know. Ask him.”

Maybe the rich will leave the flooded cities behind and we’ll get to keep their boats, to live with the water like people have always done. Maybe we will draw the new maps of a people who poetically make new out of old, who are not slaves to the suffocating idea of life as suffering/survival/interlinkage. Perhaps the new standard is whether you chose to participate in this process or not. From there, there are many ways to play, and that is fine.

As Baudrillard once said, perhaps the main rule is that the game continues. It won’t be without paradox, contradiction, and heartache. But that’s fine too. There is no blueprint. But like lovers—or like mountains that raise themselves above, while remaining within the landscape—what is certain is that it will not need your permission.