In Solitary

Amir Ahmadi Arian

March 24, 2020

I spent 2017 researching a novel partially set in a prison’s solitary confinement wing. I have been fortunate enough to never have experienced solitary myself, which is not to be taken for granted if you lived in Iran and were involved in politics like I was. For this particular project, however, that luck put me at a disadvantage. Relying on the power of one’s own imagination to render an experience of such total, torturous isolation is not possible, or appropriate. I was under the impression that obsessive research would enable me to give a plausible account of it, but it didn’t turn out that way.

After months of reading books and articles, watching documentaries, interviewing people with firsthand experience of prison, filling up notebooks with scribbled notes, I managed a clumsy approximation of the experience, but at no point in this process did I feel that I was anywhere close to capturing it. Every time I developed the illusion of adequate understanding, an interview with a friend who had experienced solitary first-hand (of whom I have quite a few, thanks to my previous life as a journalist and writer in Iran) shattered my confidence. In those conversations, I was struck by the unwillingness of my friends, some of them very close, to talk about what it was like. In one case it jeopardized our friendship.

There is a hard truth every writer learns: certain human experiences stand outside language. Probably death and orgasm are the most obvious ones. Such experiences refuse to surrender their uniqueness, their idiosyncratic essence, to strings of nouns and verbs, no matter how masterly those strings are woven. Tackling such subjects mandates extraordinary humility, combined with the anticipation of inevitable failure.

That was what those interviews revealed to me. The distortion of time and place, the enormous duress inflicted upon the confined body, the unrelenting resurfacing of the past, the flood of memories that one forgets in order to maintain sanity—all of this brings the inmate to a place where language stalls.

For a novelist, that realization is simultaneously daunting and enthralling. The most unforgettable literary moments take place at the edges of human experience: Anna Karenina throwing herself in front of the hurtling train, Raskolnikov wielding his ax over the old woman’s defenseless body, the woman in attic setting Mr. Rochester’s bed on fire in Jane Eyre. Of course, the vast majority of what is composed and sold as literature never bothers to visit such treacherous territory, which means the large capacity of literature for enriching our life remains mostly unexhausted.

Since my research had only taken me so far, I tried a last resort. Like the committed novelist I thought I was, I decided to put my body in a simulation of solitary confinement. So, sometime in the spring of 2018, when my roommate went away for a few days, I turned my room into a prison cell.

At the time I lived in a small, though two-floor apartment in Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn. Two bedrooms and one bathroom were upstairs, the kitchen and sitting room were downstairs. It wasn’t the most convenient setup for daily life, but it was conducive to self-imposed solitary. I thought that if trapped myself in my tiny bedroom and only used the bathroom upstairs, I could approximate the physical conditions of solitary confinement.

I purchased 72-hours-worth of food, less than the amount I usually eat since I wanted to experience hunger as well, even though nobody I talked to mentioned hunger as a problem. I left all screens and papers downstairs, pulled the curtains, and one morning sat on my bed in my emptied room to start this bodily phase of my research.

First came anticipation and excitement. As soon as I settled on my bed I began planning what I would do in that room, having denied myself means of overcoming boredom. I considered meditation, reviewed the possibilities of working out in that tiny space. But soon embarrassment kicked in. It was not a meditation retreat, I had to remind myself. I was supposed to have been thrown in here. I should have felt as though I would be intrusively interrogated, possibly tortured, and expect that at the end of that process a horrifying future awaited me, ranging from a few years in jail to death sentence. So I tried to focus on that situation, imagining myself in shoes of someone in similar physical conditions, yet deprived of agency, under the thumb of a ruthless punitive system.

A few hours later I gave up and went downstairs. Within a short span of time the ridiculousness of that experiment became painfully clear. No matter how meticulously I replicated the conditions of solitary confinement, the main element was missing: the state. For half a day the only negative feeling I had was boredom. If anything, those few hours generated nostalgia for my pre-internet youth in southern Iran.

As I realized then, as important as the word “solitary” is in defining the condition I sought to write about in my novel, equally critical is the word “confinement.” It makes all the difference who imposes this condition. If you intentionally isolate yourself you would gain solitude, if you’re lucky, loneliness if not. But if the police put you in the exact same room under the exact same conditions, solitude is the first thing you lose.

Solitary confinement makes your body the property of the state. It is a question of ownership, and with that, boundaries. Voluntary solitude enables us to redefine our boundaries with the world. But when the solitary life is forced upon one, those very boundaries break down. Most of the accounts I read or heard, especially from those who spent more than 30 consecutive days confined, had one thing in common: there were moments at which inmates lost the ability to determine where their body ended and the world (or, specifically, the state) began.

America is responsible for some of the worst inventions in modern history. Some are closely identified with the country: the atomic bomb, Facebook. Some, like solitary confinement, are not.

It began in Pennsylvania. Under the influence of Pennsylvania Quakers, in 1682 the so-called “Great Law” shifted emphasis from punishment to correction. Solitary confinement was the centerpiece of these reforms. The unmistakably Protestant idea underlying this new law held that people, should they be left in isolation from the outside world, including their families, would have to face their conscience and reflect on their wicked souls. This would lead them to redemption.

In their instructions for furnishing the cells of prisoners, the Quakers advised that the only book prisoners should be given was the Bible, which would structure their moral universe as they learned to renounce their sinful ways. To this day, in states such as South Carolina, the Bible is the only book given to solitary inmates.

Like other unfortunate American inventions, solitary confinement spread across the world. Now every country has its own version of it. In Iran, for example, the only book that solitary inmates are allowed to read is the Quran. Until recently Nahjul Balaghah, the sermons and sayings of Imam Ali, the first Imam of the Shia, was also available, but it was taken away because it included too many tips for resisting tyranny.

This was not a one-off, eccentric proposition. The idea of solitude as a way of cleansing one’s sinful soul emerges in numerous early theological treatises and literary texts of the 18th century. Robinson Crusoe is a case in point. It is, among other things, a novel about unwanted solitude. Crusoe ends up in the island along because he has deviated from the ways of God. After undergoing enormous suffering in the island, the castaway finally turns to God and talks to him, seeking solace and certitude. He even memorizes passages from the Bible he retrieves from the shipwreck.

It was soon clear that solitary confinement yielded the opposite of its intended result. There are early reports of inmates coming out of the solitary crushed and demoralized, with shaking bodies and shattered senses of self. Many of them likened the experience to life in a grave, an experience disturbingly close to death. Most of them never fully returned to the land of the living. A number of major figures, many of them prominent literary stars, weighed in on the subject. One of the most powerful accounts was penned by Charles Dickens as a long chapter in his 1842 American Notes. He detailed his visit to Eastern State Penitentiary, where inmates were held in solitary, and condemned what he saw in strongest words: “I believe that very few men are capable of estimating the immense amount of torture and agony which this dreadful punishment, prolonged for years, inflicts upon the sufferers.”

Alexis de Tocqueville, another shrewd observer of America, was sent to New York in 1831 to study solitary confinement at Auburn Prison and report back to the French government. In his write-up, he minced no words: “This absolute solitude, if nothing interrupts it, is beyond the strength of man; it destroys the criminal without intermission and without pity; it does not reform, it kills.”

Despite these admonitions, in the dawn of the third millennium, the practice of solitary confinement is global today. The parameters haven’t changed much since what those early Quakers set out: a cell hardly big enough for the inmate to lie down, sparse furniture, the Holy Book, silence. Except that, over time the state shed the cumbersome veneer of religious purification. Now, in the age of supermax prisons and round-the-clock surveillance, solitary confinement is blatantly and unashamedly about control and containment.

Like in other aspects of modern life, the language of neoliberalism and the free market has superseded that of religion, and instead of spiritual redemption or confrontation with one’s own conscience, we read about security and efficiency and surveillance and public safety. The early theorists aimed to save people. Instead they broke them down. The contemporary prisons are designed to break people down, to damage body and mind so thoroughly that the inmate would have a little chance of readjusting into society. It is hard to think of any other institution that achieves its goals so effectively.

Of all the narratives I heard and read during my research, the following story stuck with me the most. After 20 days in solitary, a friend of mine woke up one day to realize that words had evaporated from his memory. He couldn’t recall the names of things in the cell, or the names for things in the world outside the walls. Images kept coming to him as easily as ever, yet words refused to accompany them. So he sat there on his cot, his brain as empty of language as Adam’s after creation. Except that Adam didn’t need words. In my friend’s case, words were what he needed the most. He was going to be interrogated in a few hours, and the ways in which he would use words would determine his future.

Eventually, after a long hour of agonizing in silence, language did come back to him. It didn’t return as a whole, but in trickles, as though from a leaking faucet. He stared at the table in the room so long that eventually the word “table” (meez in Persian) materialized out of the blankness of his mind. He started shouting, “meez! meez!” like he had discovered the hundredth name of the Allah, tears running down his face. Other words followed: bed, wall, door, toilet, sink, then the names that matched his memory of what he hadn’t seen since he was thrown into that cell: bird, tree, car, mother, cat.

I was told this story over Skype, and it haunted me throughout the writing of my novel. What does it mean to write a book, thousands upon thousands of words, about a place designed to eradicate language? How is it possible to write about solitary confinement from the position of freedom?

There is no good answer for that. When Charles Dickens wrote, “I am only the more convinced that there is a depth of terrible endurance in it which none but the sufferers themselves can fathom,” he was also thinking about the insufficiency of the existing language, the fundamental inability of words to capture the solitary experience. My novel, therefore, was bound to be a failure. And I took on the challenge of writing it, fully aware that it might make me a laughing stock, if not a total idiot, in the eyes of readers who have been in solitary. But this is not to say that I regret the attempt. On the contrary, I believe that for writers such impossible tasks are the only ones worth taking on.

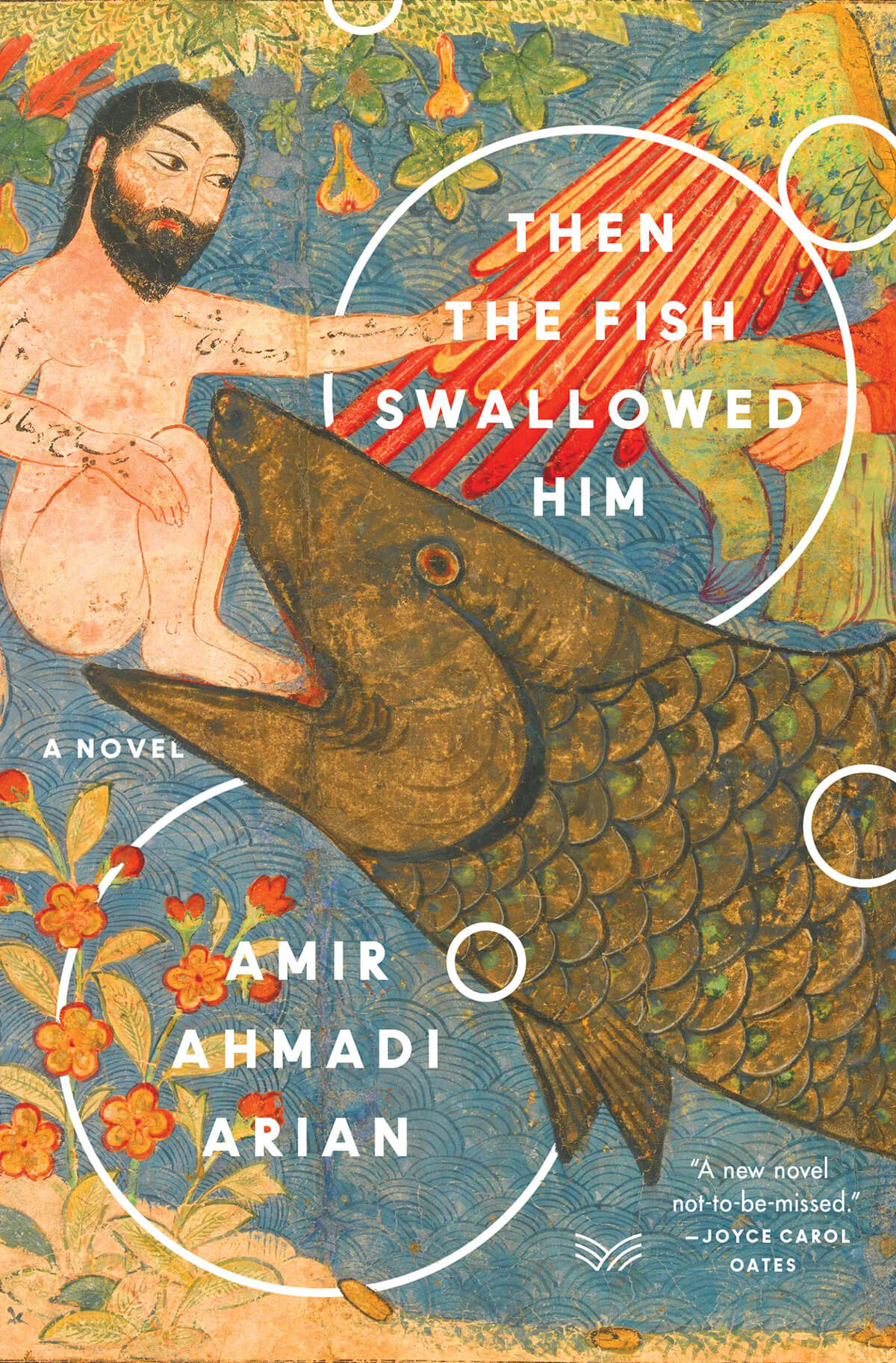

Amir Ahmadi Arian’s novel Then the Fish Swallowed Him is available from Harper Via / HarperCollins Publishers on March 24, 2020.