The Last Grand Magazine

Fiona Alison Duncan

December 21, 2021

, Hollywood (the same work of art hung in Jean Stein_s home at 10 Gracie Square).jpg)

This story was not intended to be about Jean Stein.

I wanted to know how an unusual magazine from the nineties and early-aughts came to be. That magazine is Grand Street, specifically in its second iteration under the editorship of Jean Stein, though I didn’t understand how crucial her role was when I pitched this conversation series. I was compelled by Grand Street’s mix of outstanding contributors and notable names on the masthead. This is how I came to find the thing in the first place—online shopping for used books by Mike Davis, Fanny Howe, Hilton Als, Amiri Baraka, or Antonin Artaud. I was reading them all in 2015, Grand Street had published them decades before. With one order, I became a collector. Over the next few years, I would amass a stack of the ever-relevant journal (easy at three to ten bucks per back issue) and wonder: How could all this coexist?

It is rare for money and taste to coincide, let alone with glamor, intelligence, and leftist politics. Jean Stein’s Grand Street also exhibits eros and the rough touch of the real. It is a high production journal filled with poetry and literature including many first translations, original reporting and interviews on everything from science to cinema, plus fine art portfolios. For a decade, issues of Grand Street were big-concept themed: Egos, Secrets, Detours, Dirt. This served to connect what otherwise might be hard to fathom together. Take the Models (no. 50, Autumn 1994) issue for example: there’s an interview with linguist and political historian Noam Chomsky; an essay by classical pianist Glenn Gould; a fetish-y photo collaboration between Lucian Freud, Annie Leibovitz, and Leigh Bowery; a multi-author report on ‘¡Revolución!’ in Chiapas, Mexico, including poet Rosario Castellanos in translation; a matte portfolio on an early American suburb by freak artist Peter Fend; a glossy portfolio of cocky sculptures by the now very famous artist Paul McCarthy; a testimony from Henri Matisse’s late-life nurse and model, Sister Jacques-Marie; and Dennis Hopper interviewing supermodels Kate Moss, Lauren Hutton, Christy Turlington, and Naomi Campbell.

Publishing critical darlings from an array of fields, a good sum before they became famous, others in their Pulitzer prime, retired old age, or from niches they’ve remained in, Jean Stein’s Grand Street did not simply serve, as most magazines do, the trends of her day. Although with contributors like Hervé Guibert, Harun Farocki, Toni Morrison, Edward W. Said, Darius James, Rebecca Solnit, and Paul Virilio, its eclectic curation is now, decades later, dead on trend. And I still haven’t gotten to the masthead.

What kind of magazine has Rachel Kushner as an intern? The award-winning novelist-to-be was later promoted to assistant editor. She worked closely under Deborah Treisman, now the fiction editor of The New Yorker. Everyone’s favorite emotive essayist Hilton Als was an advisory editor and feature contributor, publishing some of his early signature-style work in Grand Street. Stand-outs among the Contributing Editors list include filmmaker John Waters, journalist Robert Scheer, and the normcore trendsetting art dealer Colin de Land of American Fine Arts, Co.

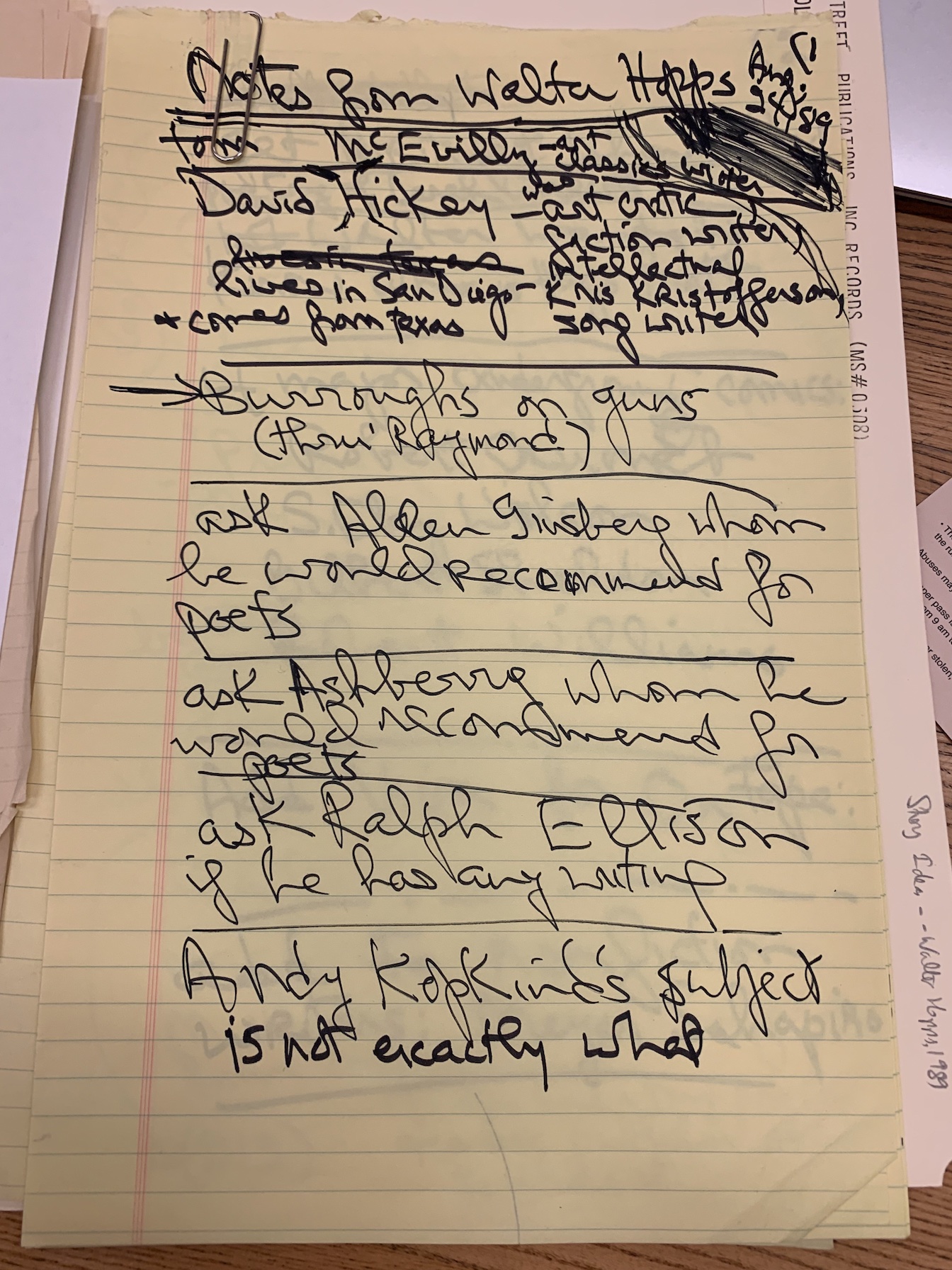

Then there was Walter Hopps. The Ferus gallery founder and museum director informed much of what makes Stein’s Grand Street special. Beyond being a confidante to Stein and a catalyst to the whole project, in his job as art editor, Hopps made use of his connections with art superstars like Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns, while presenting a newer roster who would go on to top today’s MFA candidates favorites list: Mike Kelley, David Hammons, Adrian Piper, Yayoi Kusama, Moyra Davey...

According to John Heilpern of Vanity Fair, “Jean wasn’t about name-dropping at all,” so the forty-two stars I spangled my intro with—an uncouth move maybe.

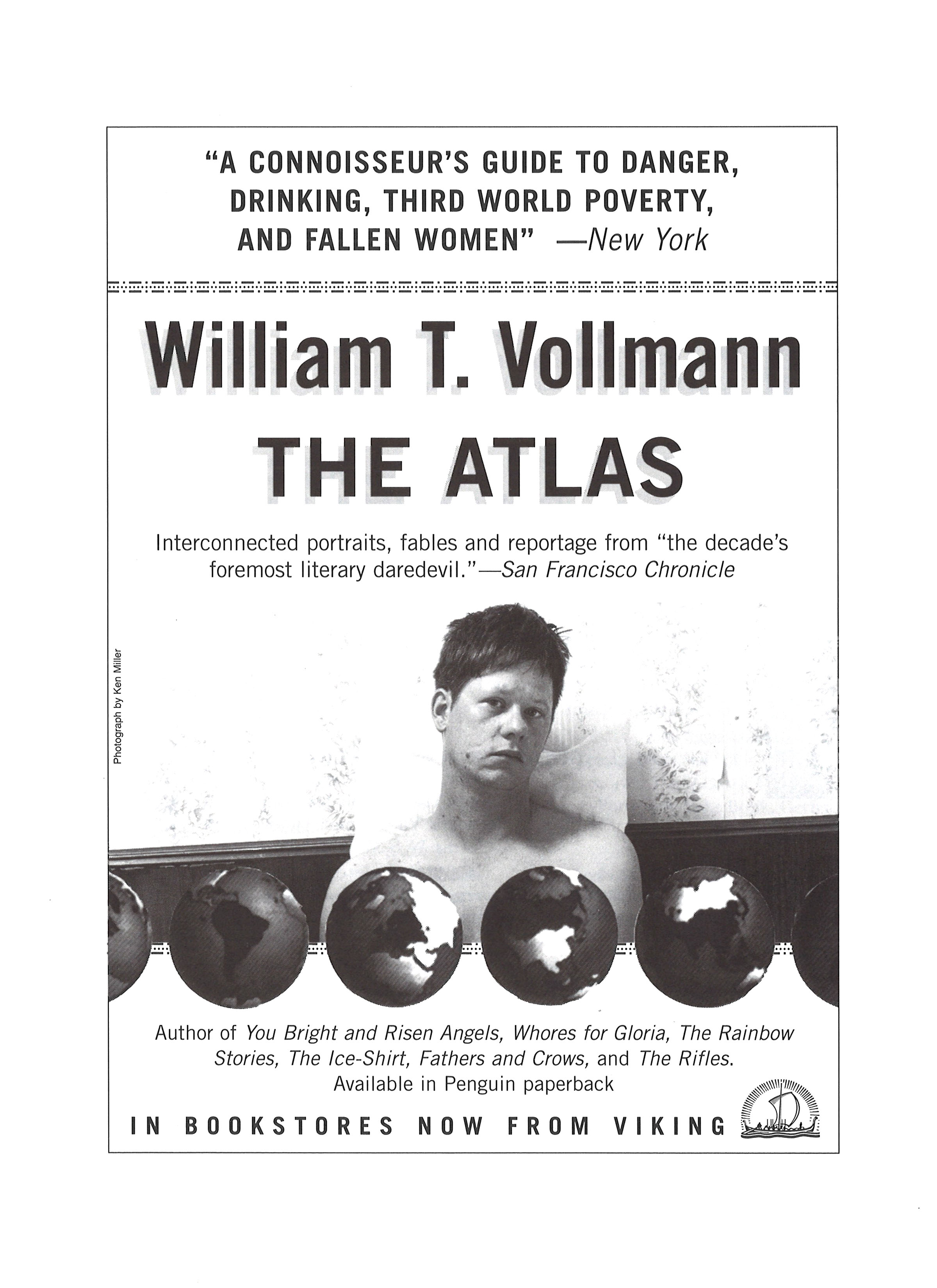

When I interviewed what former Grand Street associates I could—Hilton Als, Deborah Treisman, Rachel Kushner, John Waters, William T. Vollman, Anne Doran, Stein’s daughter Katrina vanden Heuvel (publisher and former editor of The Nation, once contributing editor at Grand Street), and Stein’s personal assistant Paul Hassett—the name they kept dropping was Jean. First-name. Jean.

A backstage mover, super-connector, catalyst, muse, and mentor—like Marjorie Cameron or Florynce “Flo” Kennedy (very different yet akin 20th-century women)—Jean Stein’s influence is incommensurate with her fame. Born in 1934, Stein was raised in Beverly Hills in what actor and director Fiona Shaw described as “a villa more than a castle—” the kind of property that comes with a name. The “Misty Mountain” estate had been occupied by Katharine Hepburn before Jules Stein, a physician and the co-founder of the highly lucrative Music Corporation of America (MCA Inc.), moved in with his wife and two daughters, Susan and Jean. When the place was later bought by Rupert Murdoch, he would keep Stein family photographs on the walls—monuments of American media history. Among those photos was one of Jean’s coming-out party, where Judy Garland had sung “Over the Rainbow.” Gore Vidal was a family friend. He introduced Jean to “literary things.” Her professional career as an editor finds its public origins in an interview with William Faulkner placed at The Paris Review in exchange, it is claimed, for being made an editor there. In 1970, Stein published American Journey: The Times of Robert Kennedy, her first of three oral histories. That was the same year she appeared as a character in Tom Wolfe’s canonical New Journalism article “Radical Chic: That Party at Lenny’s,” on Upper East Siders fundraising for the Black Panthers. “[T]hat’s Jean there in the hallway,” Wolfe wrote, “giving everyone her famous smile, in which her eyes narrow down to f/16—frankly, Jean tends too much toward the funky fallacy.” Then he goes on to detail the thirty-six-year-old’s “working girl” skirt as if this in contrast with who her father is could reveal something profound about her character.

.jpg)

Stein’s second oral history Edie: An American Biography (edited with George Plimpton) came out in 1982, a runaway bestseller on the late “it girl” Edie Sedgwick—that bleach blonde, anorexic, horse girl and Warhol muse, who was one year late of joining the 27 Club. Like fixating on a mini skirt, a book on Edie Sedgwick could be all surface, but Plimpton and Stein’s aptly titled American Biography turned out to be a substantial, chilling document of mental illness and abuse among America’s white ruling classes, from incestuous old money to overexposed celebrity. West of Eden: An American Place (2016), Stein’s final oral history, would tease readers with more devastating high-class access, including a selected and rather-humorous and high-minded account of her own family; its closing voice, a former security guard at the Stein House. “I can’t imagine why anybody would want to interview a security guard,” Gene Barnett Kerr, from El Monte, says. Stein gives the last lines in her book to him.

Because the press love this, Stein is perhaps most famous for her salon-style dinner parties where, as daughter Katrina vanden Heuvel detailed: “Norman [Mailer] and Gore Vidal would fight it out, and Robert Scheer the journalist would be on the phone to Eldridge Cleaver in Algeria.” Stein was also a quiet financier of avant-garde theatre and a vocal Jewish proponent of justice for Palestinian people, among other human rights causes. She made strategic donations as well as introductions, fast tracking careers, like that of airport bestseller and self-proclaimed genius Ottessa Moshfegh. There were also notable collaborations and frankly historical match making: At Hilton Als’ suggestion, Stein connected Matthew Barney to Norman Mailer. Their Cremaster and River of Fundament collaborations would follow.

In 1990, Stein acquired Grand Street, an American journal with European intellectual aspirations, from her friend Ben Sonnenberg for a token one dollar. For fourteen years, she would fund the publication like a grant, expanding its purview to international (including Hollywood!) arts and culture, offending some staid Sonnenberg-era devotees, while transforming the literary landscape; introducing, to give one example, Roberto Bolaño to English-language readers. Adding art, science, cinema and more to the mix, Grand Street became a home for Stein’s skills and worlds, where oral history met making history via patronage and activism and where internationalism was as obvious—and effortless—as interdisciplinary access.

What do we do with what we are born into? This question has been leading my everyday actions as my peers and I are reckoning with the world as it is and whether we can tip it in our favor. To pivot from what is expected of us, to transform what’s given and generate, not merely react, is a feat. Despite being written off, as figures like Wolfe tried, Stein stayed her radical course and accomplished far more than what is still assumed for someone of her status: throw parties, keep quiet... self-destruct. A magazine can be a wealthy dilettante’s self-indulgence. Grand Street is too specific and studied to be tossed into that pile. Not that the publication was flawless. I’ve heard it suggested—sources protected—that Stein, “a lapsed Jew, the daughter of parents who were desperate to assimilate,” as vanden Heuvel put it, did not excel at supporting Jewish literature. Likewise, the feminine arts are limited in Grand Street. While there were many female and femme visual artists in the magazine—and Stein signed off on it all—art was Walter Hopps’s job (aided by Anne Doran among others). In a letter of recommendation for poet Fanny Howe to receive the Bunting Fellowship in 1996, Stein wrote: “Howe has a voice which is strongly female, but is free of much of the critical and political weight and bias that has crippled other writers of her school.” Ouch. While true, Howe is exceptional, what about uplifting subjugated voices? Is it possible the work Stein didn’t support came from subjects not unlike herself? How we can be our own blindspots.

I hesitate to speculate much further on Stein’s motives or temper. In fact, I almost abandoned this project when I realized it wasn’t going to be a quippy history of a moment in publishing I (b. 1987) have a fantasy of nostalgia for. Why did Jean Stein have, “[f]or all her privilege and glamour,” as Phil Weiss wrote on his news site Mondoweiss, such “a keen identification with suffering people, and a pure fear of gangsters, no matter their status”? What compelled her to help fund Mondoweiss, “news and analysis [...] regarding the struggle for Palestinian human rights”? Where did her “leftist, humane” (Hilton Als); “certainly left wing” (John Waters); and “Progressive—Jean had a very strong social conscience and an unusual empathy for someone from her background” (Paul Hassett) politics come from? Why did she spend fortunes on an elite freak magazine? And to her end, lived like a millionaire. Is it fair to say she collected powerful people? Her own brand of power, where talent and discipline are what’s valuable? Did people collect her in turn? These questions came to me after my questions on Grand Street led to her. I’ll leave them as questions, admitting: I did not feel comfortable asking about anything other than the magazine. While West of Eden offers controlled glimpses into Stein’s person (on her political origins story, she recounts being set up at sixteen with the McCarthy collaborator, infamous closet-case and later mentor to Donald Trump, lawyer Roy Cohn; seeing him in trial and sympathizing with his “victim,” a supposed communist who would be “tragically” murdered in prison)—otherwise, there’s a guard of privacy around Jean Stein. And why not? If you chance or fate into a cultural nexus, born-into an extreme, are you not entitled to privacy—if you want it?

The only person I have known intimately who knew Jean Stein personally was, like her, a child of patriarchal Hollywood fame and money. I witnessed this young person judged, worshiped, mimicked, envied, and loathed, given more access, capital and power than anyone, let alone a kid, should have. They would often cite Jiddu Krishnamurti’s The Dissolution of the Order of the Star, denouncing celebrity, saviors, charismatic leaders, and false gurus. Ironically, they behaved like all of those things, teaching me the danger of trusting actors. I met this person after I had started collecting Grand Street. One of those synchronicities. I remember them flipping through one of my back issues after they’d learned that their friend Jean Stein had committed suicide. On April 30, 2017, she jumped from her penthouse apartment balcony. She was 83. Our mutual friend was devastated and not surprised, not by courage nor the tragedy of her final action. Stein had been struggling with suicidal depression, as many with great empathy do, for years.

Perhaps I’m playing innocent; a part of me knew I would learn about the mysterious Jean Stein in pursuing my curiosity about Grand Street. If that’s true, it’s yet another example of me clumsily seeking intimacy with people I admire through the safety of media. A project, an excuse. Were Walter Hopps and Jean Stein still alive, a history of Grand Street would no doubt be about others—through them. As it stands, likely due to the recentness of Stein’s death (Hopps passed away in 2005), the following oral history on Grand Street magazine conducted in mid-2020 doubles as a portrait of one woman of taste, discernment, access, resources, and motivation; as curious and understatedly bold as the magazine she would publish.

*

KATRINA VANDEN HEUVEL (PUBLISHER AND EDITOR OF THE NATION, FORMER CONTRIBUTING EDITOR OF GRAND STREET AND STEIN’S FIRST DAUGHTER) Grand Street was of its moment and it had this extraordinary cohort. It was a cacophony of people with their worlds and their ideas that became the journal. Walter [Hopps] was in a sense a co-spirit, a co-editor. Walter was extraordinary. A polymath. He and my mother had been, it sounds old fashioned, boyfriend and girlfriend. They had a long relationship. And they remained the deepest of friends and spiritual comrades. Grand Street was very much his vision too, visually. Anne Doran did the oral history with Walter. There was someone called Andrew Kopkind, a brilliant writer who should be better known. In fact, Andy to a point informed her political edge. The other one who was critical was Edward Said, who was not only a deep literary scholar, Conrad scholar, and very political, but an extraordinary musician. A concert pianist. So he brought some musical ideas. Torsten [Wiesel, Stein’s ex-husband, the Nobel Prize winning neurophysiologist] was important in terms of science—and he loved to weigh in about poetry. Norman Mailer was lurking around, although I think he played more of a role with Edie. Deborah [Treisman] was key. Look at Deborah—she’s now the fiction editor of The New Yorker. In terms of her favorites, she [Stein] loved Bill Vollman because he was just the classic absurd. She loved underdogs and others. Ottessa [Moshfegh] became a very important mentee. I believe they had a falling out toward the end, but Ottessa wrote a remarkable poem-tribute to mommy after her death. So many of those who she published would go on—Hilton...

HILTON ALS (AUTHOR OF WHITE GIRLS AND THE WOMEN, PULITZER PRIZE WINNER FOR CRITICISM, FORMER ADVISORY EDITOR AND FEATURE CONTRIBUTOR OF GRAND STREET) You should know that Grand Street is inseparable from who she was. When we speak about Jean—you see it’s funny, I was going to say this about Grand Street but her name keeps coming up. When we speak about Grand Street, I think it meant a lot to Jean because she finally felt she could have something of her own. When you grow up in circumstances like hers, you’re on display because you’re the child of etcetera. Grand Street made her feel that she was making a real change in people’s lives. She made a big difference in my life. Also we laughed a lot together. I remember writing certain things but I also remember it was a continuous feeling between us of exchanging ideas and stories and so on. I don’t think anyone is operating on that philanthropic level vis-à-vis publishing now.

, Dirt (1).jpg)

ANNE DORAN (WRITER AND ARTIST, FORMER ASSISTANT ART EDITOR OF GRAND STREET) Jean came from great wealth. When her mother died, a certain amount of the estate had to be devoted to the arts. After a couple of false starts, Jean decided that she and Walter should support writers, translators, and artists through an art and literary magazine that paid well for contributions. Jean bought Grand Street from its founder, Ben Sonnenberg, for $1.00 and Walter’s idea was that what had been a straight literary publication could become something like Flair, Fleur Cowles’ [1950-51] magazine. Flair folded after 12 issues because even back then it was too expensive to produce. Jean, likewise, lost a lot of money on Grand Street. In every issue, there would be a portfolio of work coming straight out of the studio of an historically important artist. Walter was very close to Robert Rauschenberg and Bill Eggleston. Jean was friends with Saul Steinberg. Both of them knew Jasper Johns. Grand Street rapidly overtook any amount of money that Jean’s mother had left. [Laughs] It started losing much more money. It went from two art portfolios up to eight.

DEBORAH TREISMAN (FICTION EDITOR AT THE NEW YORKER, FORMER MANAGING EDITOR OF GRAND STREET) Grand Street was one of a kind at that point, in terms of the combination of cutting-edge fiction, nonfiction, poetry and visual art printed with great care. There were no other magazines at the time that had that particular combination, and it was Jean bringing these things together. She moved through these worlds.

My responsibilities... It was everything from working with Jean to decide on all content, finding, soliciting, reading the material, editing, copy editing, getting it all into layout, dealing with the proofreader, the printer. Every word in the magazine went through my computer, and there was a great satisfaction in that. Jean had to sign off on everything. We worked out of an office on a floor of a building on Varick Street, just south of Spring Street, that has since been taken over by Manhattan Mini Storage. This one floor was sublet from the New York Foundation for the Arts, I think; it had various nonprofit arts organizations on it. Jean didn’t work in the office. She was in touch by phone and fax, often leaving long voicemail messages and sending long faxes in the middle of the night with her distinctive, large, curvy handwriting. I can still reproduce her signature, which I had to do from time to time. We were downtown on the West Side. She would come in for meetings, but she was at the opposite end of the city, up on 84th at the East River. That apartment, which was kind of a doomed space, had belonged to Gloria Vanderbilt and was where her son had jumped to his death. And that history kind of hung over it. Jean hadn’t really wanted to move there.

RACHEL KUSHNER (AUTHOR OF THE FLAMETHROWERS AND THE MARS ROOM, FORMER INTERN AND ASSISTANT EDITOR AT GRAND STREET) I lived to go there and be in that office, which was on Varick Street. I remember the smell of the office—it smelled like the very high quality and expensive paper Grand Street was printed on. I guess I was 27, which is a bit old to be an intern. But I’d only been a bartender and had never worked in an office in my life (and had never planned to). Deborah Treisman was the editor, and a very special conduit between the sensibilities of Jean and the people who influenced Jean, and the editorial staff who really brought the magazine together on a practical level. Deborah is a very unusual person for how highly skilled and calm and capable she is, and that capability set the tone in the office. As an intern I got to read through galleys and find and suggest excerpts, which was a big part of my duties. Such as Roberto Bolaño’s first piece that was published in English, “Phone Calls.” (I later read that Barbara Epler discovered Bolaño through Grand Street, which is amazing. I actually thought we had been tipped off about him through her.) The memory of Walter remains incredibly vivid in my mind. He would come in the office and smoke—the only person who was allowed to smoke in the office—and talk at length in grammatically perfect sentences. He really did have a photographic memory which is usually untrue when people say it, of someone. Of Walter it’s true.

Walter gave Andy Warhol his first West Coast show. He brought Yves Klein to the Mojave and told him it was Death Valley. The stories he told were rich and various. I remember going to see Touch of Evil with him and Anne at Film Forum, after we’d edited and published Orson Welles’ director’s notes for the movie. Walter sat between us and whispered stories about living in Venice when they filmed it, and how he and Robert Irwin and some others got by for a week stealing hotdogs from the craft tables.

Now, living in Los Angeles, and occasionally running into people like Billy Al Bengston or Ed Ruscha who showed at the gallery, Ferus, that Walter ran with Ed Kienholz, my understanding of who these artists are, and where they come from, is totally shaped by the influence of Walter Hopps.

.jpeg)

PAUL HASSETT (PERSONAL CHEF AND ASSISTANT TO JEAN STEIN) Calls to Walter, that was almost daily while Walter was alive—a call to Walter.

DEBORAH TREISMAN Jean relied on certain people in her life to inform her opinions. Walter Hopps was one of those people. Another was Andy Kopkind. After he died, she turned often to Edward Said. She just adored him. If she wasn’t sure about something, she would run it by him and then quote his opinion. There was a room in her apartment she called the “Edward Said room.” A little parlor off the living room, decorated in a style he approved of.

RACHEL KUSHNER There was a specific chair in that room that people were always seated in when they were going to be fired. Once I was called up to the house by Jean and Torsten. I wasn’t sure why. They didn’t give a reason, just that they needed to speak with me. Ben Anastas, who was Jean’s assistant at the time, and later an editor at Grand Street, and a very witty, really great person, brought me into the Edward Said room, and whispered, “Don’t worry. They told me to seat you on the couch.” Meaning I was not going to be fired.

JOHN WATERS (FILMMAKER, ACTOR, WRITER, AND ARTIST, FORMER CONTRIBUTING EDITOR AT GRAND STREET) I knew Grand Street mainly through Jean. I think I first met her at a fancy art dinner party. I was seated next to her and she was mean to me because she thought I was some rich guy from the board of the museum. Then she found out I was me and she was nice. She bought one of my pieces, a really early one entitled Zapruder which was photos of Divine as Jackie in the Kennedy assassin, which could’ve been awkward since Kennedy relatives sometimes visited her apartment. She and I became really good friends through my art dealer at the time, Colin de Land. I hung around with her a lot and I always went to her amazing dinner parties, she introduced me to a million people. You’d go to her house and you’d be seated next to a heart doctor or the biggest architect. She really did have a salon. She helped get me Bill Clegg as my literary agent. Whenever she asked me to do anything for any project that I was working on I jumped to it because she was such a great woman and so smart and funny and she understood what I was doing really well. I remember I did the Mike Kelley piece for Grand Street—that sticks out. I think it was called “The Dirty Boys.” I don’t remember whose idea that was, probably hers, especially if it was in the Dirt issue. What else was there? The Mo B. Dick interview—she was the first drag king I saw do an act. She was in A Dirty Shame [Waters’ 2004 film]. Mo B. is now married to a man. She came in! I think it’s exciting. Apparently she’s not a lesbian anymore, she’s not trans, she’s not a drag king. She’s a straight-ish woman I guess. Beyond came in. She’s always been great, no matter which identity she had. I like that. I think that’s the new freedom.

Jean wanted to be controversial, she liked to push the envelope, all those cliché terms that now everybody uses, she was before they were. It worked for her. It always did.

WILLIAM T. VOLLMAN (AUTHOR AND JOURNALIST, FORMER CONTRIBUTOR TO GRAND STREET) I met Jean Stein through my agent at that time, who was not successful in selling any books for me (although they did get the commission for a British book that I sold)—the only thing they did for me was to hook me up with Grand Street, and for that, I am grateful. That’s how I met Jean. She was a wonderful friend. I always felt that one of the few things that I could do for Jean was not ask her much about anything, because people were all the time bothering her about this or that, so my thing would be, “Jean, let me take you out for dinner, and we don’t have to talk about much of anything.” The Lucky Star [Vollman’s 2020 novel about a magical woman, set in San Francisco] is dedicated to Jean. It’s the first book that I’ve published since her death. Too bad this article is online. It just means once the solar storm comes all your work will be for nothing. Those bits and bites are not very stable. But it’s not my problem. If you’re okay with it, who am I to carp?

DEBORAH TREISMAN What interested Jean were things on the edge—people who were working far on the margins, or early in their career, or doing something unconventional in whatever way. She was interested in things that felt unexpected, not mainstream, but, at the same time, essential, important, ground-breaking. That attitude on her part meant a lot to me. I’m sure you’ve heard from other people that she wasn’t always easy to work for—she could be erratic, change her mind about things at the last minute, or suddenly send a flurry of faxes with new edits on something I thought was ready to go, she asked a lot of the people who worked for her—but she also had this just remarkable openness to people who were making art of any form, she had a kind of alertness to it. It thrilled her.

ANNE DORAN My job was to rustle up work by younger or less well-known artists of interest. Both Jean and Walter were very adventurous in their tastes. On the literary front, Jean, especially, didn’t just have a nose for talent, she had a nose for talent that was going to go somewhere. Walter had a legendary eye for art and an unbounded appetite for looking at it. On my side, I tried to give them suggestions for art they could sink their teeth into. None of us were really interested in what was safe. Of the portfolios I suggested, one I’m especially proud of is the excerpt, in Grand Street’s Fall 1998 issue, from Susan Meiselas’s project Archives of Abuse (1991–92), which brought together police reports and forensic photographs documenting domestic violence. It’s hard to look at and hard to read, but it is an incredible piece of photojournalism. Another was a selection of artworks by Adrian Piper.

DEBORAH TREISMAN The Hollywood issue of the magazine was the first one I worked on from start to finish. It came out right before Book Expo, which was held in L.A. then, and Jean threw a huge party for it at Dennis Hopper’s house in Venice, which had been designed by Frank Gehry. It was a memorable night. I remember seeing Ralph Fiennes talking to Paul Schrader, and there were various other people that I hadn’t envisioned meeting at age twenty-four. Later, we had the Egos issue, with a cover and portfolio by Julian Schnabel, for which Jean and I made a studio visit to Schnabel’s home in the West Village. I was supposed to be meeting Jean there, and he had clearly prepared himself to be working as we arrived. But Jean as usual was late by a good half hour or more—she was always late.

PAUL HASSETT She was always late. She was notoriously late. [Laughs] For everything. She was one of those people—there’s always something else you gotta get it done before you go. At different times, I think it was a tactic, to be in control. It depended on the situation and what the meeting was about. And sometimes she didn’t want to go. That could be part of it.

DEBORAH TREISMAN So I was there and he [Schnabel] wasn’t quite sure whether to put the show on for me or not. We had some awkward moments where he’d put paint on the canvas and then instruct his assistant to take it off. Or he’d come over to me and bark at me to roll up his sleeves for him. He clearly wanted to put these marks on the canvas while Jean was watching. Editing Grand Street involved a fair number of entertaining moments like that. There were some people who, predictably, had big egos and others who were nothing but charming, John Waters being one of those.

WILLIAM T. VOLLMAN The editorial process was quite simple, easy. I’m someone who doesn’t like authority in any form. So I don’t like much editorial interference. And they didn’t give me much...

RACHEL KUSHNER As an intern I was sent by Mike Davis [activist and author of City of Quartz and a Contributing Editor at Grand Street] to purchase a stack of books for a man named Daniel Lee Anders that Mike had been corresponding with who was serving a life sentence and was in solitary confinement in I think Arizona. These letters were edited and published in Grand Street as “Letters from the Hole.” Among the books Daniel Lee Anders wanted was Thomas Paine’s The Rights of Man. I bought it and sent it to him. This made some kind of impression on me, as someone who had always thought about incarceration, and had been exposed, by family and childhood, to people who had gone to prison. Just recently I had to call Mike Davis to interview him for an article, and we talked a lot about the moral stamina that is required in doing a certain kind of work, of advocating for people doing life, as I now do.

, Secrets.jpg)

Another incident that was personal to me was when Jean asked me to go visit Brigid Berlin, formerly Brigid Polk, who was friends with Andy Warhol and an amanuensis for him, and appeared in a bunch of his films. Of course Jean knew all those people from her Edie book, and I know she always really liked Brigid’s sister, Richie Berlin. Brigid Berlin, though, was a handful. I rode my bike up to her apartment and I brought flowers for her: she was a Warhol superstar and I was an obscure nobody and wanted to be reverent, I guess. Her apartment was filled with fake flowers and I mean filled: like a horror vacui of fake flowers. She said she detested real ones and that they made her nervous because organic, thus filthy, and she threw mine in the trash. She offered me wine, but did not, herself, drink. I was there for maybe seven or eight or nine hours. She talked into a microphone and I just kept changing tapes. She told me all about her childhood, growing up with a father who was president of the Hearst Corporation, and how her father had introduced Joe McCarthy to Roy Cohn and how people like Louella Parsons would come to dinner. She told me about eating as a form of rebellion in her incredibly privileged but very cold upbringing, how she’d sneak down to her father’s bomb shelter and cook herself a giant pot of spaghetti. Her stories and her way of telling them was amazing, but also kind of overwhelming. At the end of the visit, she gave me an artwork of hers, a “tit print,” which I still own. After that, she called the office regularly to speak to me, and Anne, or whoever answered, would say, “Hey Rachel, it’s for you haha,” and then they’d all laugh knowing I was going to be on the phone going uh, huh, uh huh, uh huh, for the next several hours. But these communications resulted in a gorgeous piece by Brigid Berlin that appeared in issue no. 68 Symbols. Listening to her and coming to understand how she thought and what her American century was definitely informed my understanding of Warhol and that whole crowd. She showed me the ashes of about eight different pugs that had all died, and she’d made these needlepointed likenesses of each one. The level of obsession and certain ideas about fame and money and kitsch. Also, the kind of casual cruelty that was at the heart of the Factory, and Andy’s attraction to wealth and power, and in particular, to these women who were kind of American heiresses, like Brigid. He was dead by the time I met her, but Andy was her real audience, when she spoke: not me. It was Andy who would have wanted to hear her recount this meeting, in the back of a limousine, between Joe McCarthy and Roy Cohn.

JOHN WATERS I think Jean was interested in anybody that kind of had obsessional interests. And she was that person herself. Publishing I think that was her obsession because I certainly don’t think she made a lot of money. I’m sure she lost a lot of money, and it was her money. She was like a grant herself to even have this magazine and to cover the people in it whose careers that magazine certainly did help.

WILLIAM T. VOLLMAN Bob Guccione [founder of Penthouse magazine] one time tried to help Jean. He said, “You know Bill, I looked into it and for every copy of the magazines she sells, she loses eight dollars. That’s no way to run a business.” But of course if you were Jean, it was okay. She started feeling guilty when she thought of this organization she had to increase awareness of and reduce use of landmines—she started thinking that was a more important thing. But I thought Grand Street was great.

PAUL HASSETT I really don’t think Jean viewed it as a loss. I think she viewed it as her funding something she thought was important, that wouldn’t be there otherwise. She always contributed a lot to New York City art institutions, which I don’t think she got as much personal satisfaction as what she did with Grand Street.

ANNE DORAN Jean was such an interesting mix of influences and impulses. On one hand, she was a renegade; she built her life around being a champion for work that didn’t necessarily have mainstream appeal. On the other hand, Jean was her father’s daughter. Jules Stein was a Hollywood mogul, and something of that was bred into Jean’s bones. Walter once said to me, “Jules Stein always paid attention to the box office.” In other words, how many people he was getting in the door. The part of Jean that wanted to support advanced art and writing was perpetually in conflict with the part of her that wanted Grand Street to be a bigger deal. She had multiple reasons for folding the publication, but in the end, my personal feeling is that while she deliberately set out to create something that would be, in her own words, outrageous, she was, in the end, disappointed it didn’t do better at the box office.

, Egos (cover).jpg)

RACHEL KUSHNER After issue no. 69 Berlin, Jean and her co-publisher and husband, Torsten Weisel, had begun to talk pretty often about ending the magazine. I think Torsten didn’t want the expense any longer, which, then and now, seems like a shame. It was Jean’s money. And the magazine brought focus to her very special talents and sensibility.

KATRINA VANDEN HEUVEL She was a great editor. She had a great sense of tone, she was fastidious. She worked crazy hours. She believed in translation as an important cultural force that was not supported and she used quite a bit of Grand Street’s resources to support translation. She loved working on manuscripts, and on the visual. She loved it. But then you know so much of it was about the people. My mother was deeply collaborative and was inspired by others’ ideas and would run with them. And she had a sense of who she trusted, not just personally, but politically, visually, editorially. She was a tough judge. She was tough. I don’t have the dates in my mind, but I think there was a quick succession of people passing. Walter died, Edward died, Andy died, Deborah moved on. It was not as if she didn’t have her own strong ideas, but she missed that process of collaboration with those she admired. She tried to piece it together with young talented people, but she had lost some of the joy of doing it, it had become more arduous.

ANNE DORAN I think one of the most important things to remember is there weren’t many magazines like that. There are a lot of journals now that have art and literature (by the time Grand Street closed, there were enough of them to fill a whole bookshelf at my local independent bookstore), but at the beginning, there weren't.

HILTON ALS I was just really grateful to be published... And I’m wondering if I spent too much time being grateful... But I did it anyway. And then there was a rift, that doesn’t concern your story, but it was a mistake that she [Jean Stein] made and that she apologized for but it was a great sadness to me and I cannot remember what year that happened, except it probably coincided with me not doing stuff there anymore.

My first glimpse of her depressions was [earlier], we took a trip together—separately but together—to the Hotel Bel-Air. She was going to give me a Hollywood party, and who did I want to invite? I said Jennifer Jones. Jean had incredible access to all these people. And because they liked Jean, they liked you. That was one of her gifts. She had been involved with all these people in one way or another, and she had inspired a kind of trust in them that made them trust you. Anyway I went to Jean’s room. She wouldn’t let me in her room, she was crying. She opened the door a little bit, and she said, “I’ll see you later.” That was my first indication of a side of her that was in pain. I think what happened was that she would feel really exposed in intimacy. You would be very close for many years, as we were. She made you feel that you were the only person available to her and that you had complete access to her. And then she would do something that changed that. She would want to have some sort of distance between your former intimacy and who you were together. It was very difficult for her to maintain that kind of intensity after a while because she felt very exposed in that.

PAUL HASSETT She got me to tell her things that I would have never told an employer or anyone other than immediate family. Sometimes I would leave at night, going oh my god [laughs]. There was no one who could get people to talk like Jean. She had a way of weaving around and getting behind things that disarmed whoever she was interviewing. She used it throughout her life to get what she wanted out of people, and I think she used that in the magazine as well. She had a way… Disarming is a great word for Jean.

DEBORAH TREISMAN I learned so much from her. Her skills as an interviewer—her ability to get people to talk was just uncanny. She did it, not necessarily by playing dumb, but by looking surprised or as though she wasn’t perhaps getting what someone was saying and they would elaborate. And they would want to tell her because she had such great reactions, you know? She would emote.

JOHN WATERS She was eccentric and always the same kind of person, except at the end when this terrible depression that no one could really do anything about overcame. But I even said, she wasn’t of a sound mind when she committed suicide or she wouldn’t have done it at home to bring down the property of value of her apartment for her children. I said that at the funeral and everyone laughed.

*

That oral history was conducted from February to May 2020, with a few follow-ups in August and October. I want to thank everyone involved for indulging my curiosity, and for their honesty. To my regret, I was not able to connect with Mike Davis or Ottessa Moshfegh. Moshfegh declined to comment. I was curious about an ideated 2014 online reboot of Grand Street, for which Moshfegh was tapped as an editor; there’s evidence of this in Jean Stein’s archives at the New York Public Library. Later, I also came to wonder about the parallels between Moshfegh’s blockbuster novel My Year of Rest and Relaxation and Stein’s final years.

Mike Davis called me back once and I missed it. I tried him a few more times but never got through. One of my favorite notes in the Grand Street archives at Columbia University came from Davis. It’s a list of ideas for future issues. Among the themes he suggested were “Mayhem,” “North,” “Shelter/Home/House?” and “Kindness—the most edgy thing of all.”