The Mourners: An American Mood

John Vincler

January 2, 2019

The Mourners. I don’t know exactly when I first discovered these 15th-century sculptures made to decorate the tomblike memorials of the Dukes of Burgundy. Carved in pale alabaster, nearly devoid of color, these diminutive monk-like figures fascinated me. They were objects I thought toward, images that I would attempt to recollect. Increasingly, I see resemblances in other artworks that seem to be their direct descendants. I have returned to The Mourners again and again as personal objects of contemplation (maybe even devotion). Looking at them, it is as if they are still asking: What are you hiding (or hiding from)? What are you mourning?

*

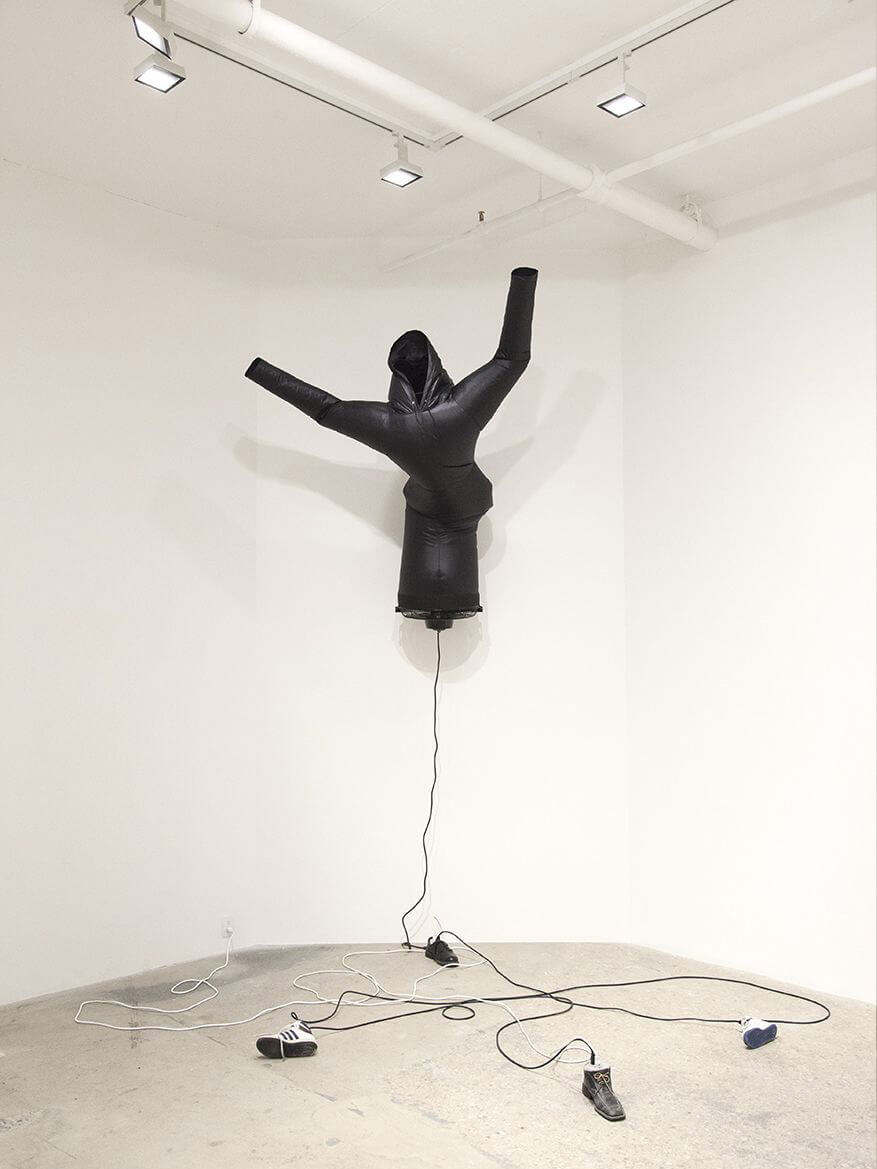

I thought to The Mourners when I saw Paul Chan’s hooded figures lash about with the convulsions of a Twitter feed—first at the Guggenheim in 2015, and then two years later at Greene Naftali Gallery. Chan’s sculptures seem ever more prescient in capturing an American mood—part bogey man, part mourning figure, and hauntingly mostly just full of air. Take for example the single wall-mounted sculpture “Pillowsophia (after Ghostface),” 2016. The punning title itself evokes a current air of political depression: what sort of wisdom (sophia) is soporific? Or perhaps the title defers wisdom altogether, suggesting that wisdom is asleep?

This body of work has a particular resonance for me. I was born in Detroit and my father has worked for decades in automotive factories. Chan adapts the carnival-barking form of the spastic windsock men used to advertise car dealerships, the ones that profit off of exorbitant loans. No credit, bad credit, no cash down. Cut the power to the fan and the figure flattens into a pool of nylon on the gallery floor, resting among the discarded shoes (that are also part of the same sculptural assemblage). In this work, I see an emblem of an inflating-deflating debt bubble, and something more than this, a silent oracle bespeaking only loss.

*

Like the small sculptures of servants buried with the pharaohs, The Mourners were only a minor feature within a complex sculpture mediating life and death, the earthly and the divine. Commissioned by Philip the Bold, the Duke of Burgundy, around the year 1377 to be housed in the chapel of a Carthusian monastery, ensuring that the actual monks housed there would pray for his soul. When the Duke died in 1404, the tomb remained unfinished until all of the elements were finally brought together in 1410.

The Mourners were set in place in architectural niches underneath the supine Duke, made to seem as if they were circling in an eternal procession. (Though the polychrome sculpture of the Duke is life-sized, it is not a proper tomb; the Duke’s remains are not contained inside.) Philip the Bold’s son, John the Fearless (1371–1419) would commission a similar funereal monument, incorporating effigies of both himself and his wife Margaret of Bavaria, to rest in the same chapel as his father’s, with a matching set of near-duplicate mourners circling beneath the double tomb.

The other aspects of the tomb—the sculpture of the Duke, the architectural embellishments, and the accompanying lions and the angels at the Duke’s head—are of little interest to me. I prefer to remember The Mourners detached from their original context, as they were shown at an exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum in 2010, on a rare occasion when they left their home, the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Dijon, France. Wrestling the mourners from beneath the tomb structures was a project that began with the French Revolution, after which their original charterhouse home in Saint-Bénigne was re-baptized a “Temple of Reason.”

The memorial sculptures of both father and son were dismantled. The hands and faces of the effigies of the Dukes, which had been mutilated, were removed, (the lions, angels, and arcades were put into storage). Several mourners disappeared or were acquired by collectors. Only seventy of the eighty mourners were transferred to the Musée des Beaux-Arts in 1794. Three were later returned. A few others are in museums (notably the Cleveland Museum of Art) or private collections. Two have never been seen since. In this way, I like to think of The Mourners—viewed collectively and removed from their service to the Duke—as a revolutionary work of art, a transformation of a 15th-century work continuing from the 18th century to today.

*

I link them not only to the figures of servants buried in ancient Egyptian tombs, but also to the surviving (and surely ancient) tradition of hired mourners that persists today, like those whose vocalized laments featured in the contemporary artist Taryn Simon’s massive installation An Occupation of Loss, held in New York’s Park Avenue Armory in 2016, that brought together more than 30 mourners-for-hire, creating a polyphony of laments from varied (Armenian to Yezidii) traditions across the globe. This globalized, scaled-up reenactment of The Mourners would likely be impossible only a few years later as a result of Executive Orders 13769 and 13780—the so-called travel ban.

*

The question of authorship is a vexing one. The initial commission was taken on by Jean de Marville, the Master Mason of the Carthusian monastery. After he died, the workshop was taken over by Claus Sluter, the single name most commonly ascribed to the completion of The Mourners. But they remained unfinished at the time of Sluter’s death in 1406, only to be completed by Sluter’s collaborator and nephew Claus de Werve.

When I think of the late-medieval mourners, I have to remind myself that I am not thinking of the sculptures probably designed and executed by Claus Sluter. Instead I am recalling the nearly identical copies created by Jean de la Huerta and finished by Antoine le Moiturier, commissioned for the joint tomb of John the Fearless and Margaret of Bavaria, completed and installed in 1470—some 50 years after the death of John the Fearless and 60 years after the originals were installed. These copies were the sculptures exhibited at the Met, the ones appearing in photographs online, and in books that have sat for years now at the edge of my desk.

*

The mourners’ robes, rendered in uncolored alabaster, would have been distributed to lay persons who lacked religious garb during a funeral ceremony, making them look much like the Carthusian monks of the charterhouse where the figures were housed. Though some of the sculptures depict Carthusian monks, I find the most anonymous figures, the lay persons, to be the most compelling, especially where the human form is almost entirely lost in the draped folds of the robe, like the one where a hand is brought to the face obscured by the robe’s hood (to wipe tears away, perhaps, or to cover the nose and mask the smell of death).

This effect can be traced to the origins of Western art. Pliny the Elder, in his Naturalis Historia, written in the first century of the common era, describes the great ancient Greek painter Timanthes and his famous painting of the sacrifice of Iphigenia. The painting shows Iphigenia at the altar awaiting her death, while those around her are overcome with grief. Kalchas, Odysseus, and her uncle Menelaos are shown in their robes, with faces full of sorrow and tears. Agememnon raises his sleeve to veil his face as he awaits the imminent loss of his daughter.

Pliny writes that Timanthes “is the only artist in whose works more is always implied than is actually depicted; his execution...is always surpassed by his ingenuity.” This voltus velatus (covered face) or tristitia velata (veiled grief) is also recounted by Marcus Tullius Cicero and Quintilian as a moment of artistic innovation using Timanthes’ portrait as an example of revealing more by showing less, making the viewer imagine what is intentionally kept hidden.

*

David Hammons’ “In the Hood” (1993) consists of a faded black hood roughly cut from a sweatshirt and mounted to the wall. The only perceptible alteration to this fragment of cloth is the insertion of an arc of wire, which creates a ghostly cavity within the hood where the black fades further into darkness. In this deftly minimalist intervention, I see a direct link to Timanthes stripping away all unnecessary visual information.

The philosopher Giorgio Agamben has traced the symbolic origins of monastic garb to the fifth-century Cenobic Institutions, by John Cassian, also known as John the Ascetic. This first book is titled “De habitu monachorum” (“On the Habit of Monks”). As Agamben writes, “The monks’ clothes, which Cassian enumerates and describes in detail [are] the symbol or allegory of a virtue and way of life. For this reason, to describe the exterior dress (exteriorem ornatum) will be equivalent to revealing an interior way of being (interiore cultum…exponere; ibid.)…. Thus the small hood (cucullus) that the monks wear day and night is an admonishment to ‘hold constantly to the innocence and simplicity of small children.’”

After a photograph of Hammons’ work was used to illustrate the cover of Claudia Rankine’s 2014 book Citizen, much has been made about the fact that the work seems to iconically prefigure the symbolic power of the dark gray sweatshirt worn by 17-year-old Trayvon Martin on the day he was murdered. Martin’s sweatshirt was displayed in court as evidence, encased in a translucent niche inset in a rectangular board, arms outstretched like Christ. A “Million Hoodie March” was organized in protest of the initial failure to arrest and charge Martin’s murderer. Hammons’ sculpture prods at how exterior dress is read as linked to an interior way of being. It is a substitute relic, imbued with its own silent wail, a fragment of a contemporary American mourning figure.

*

I first discovered The Mourners while researching the relationship between early Netherlandish panel painting and miniature illuminations in medieval manuscripts. I ran across them when tracing the particular history of grisaille (greyscale) figures in manuscript miniatures and panel paintings, like the pair of figures seen on the central lower exterior panels of Hubert van Eyck & Jan van Eyck’s Ghent Altarpiece (1432). These greyscale figures looked to me like unpainted sculptures, which scholars have suggested may have been directly inspired by the evocative forms of Claus Sluter’s sculptures. It was chasing these visual genealogical threads, like footnotes, that I first discovered The Mourners.

Around the same time, I learned of (or at least first truly paid attention to) the work of Michaël Borremans. The contemporary Belgian painter is, to my mind, the closest living artist to the work of the early Netherlandish masters. I was particularly taken by Borremans’ attention to cloth—how it is evokes just as much as the faces and bodies of his subjects. (The eyes of his figures never look out at the viewer, the gaze always cast elsewhere; his work is no less engaging for this, it is somehow only more contemporary.)

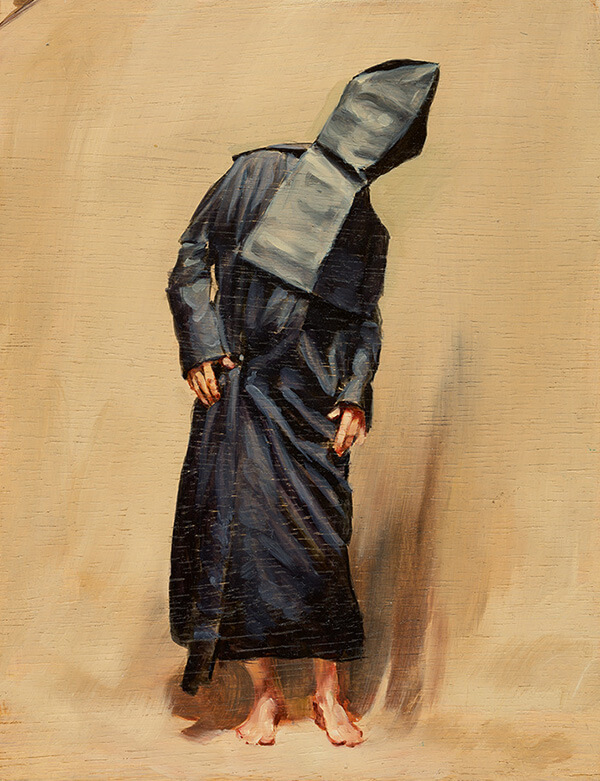

In his Black Mould series, exhibited by David Zwirner in London during the summer of 2015, the figures’ faces are obscured by a covering too thick to be a veil and too totalizing to be a hood. A figure is repeated in the paintings, the first 18 of them sharing the title “Pogo,” a name seemingly out of Samuel Beckett, with “Pogo” sitting somewhere between Beckett’s Pozzo and Godot from his most famous play. In the theater-like desolate landscape of Borremans’ series of paintings, I see a sort of mute sequel to Waiting for Godot.

It is as if Borremans has set himself the task of painting a portrait that fuses both a judge on the dais of the highest court and the hooded figure in Abu Ghraib standing on that box, his fingers connected to what he is told are electrodes—a figure fallen out of history, debauched and unhinged. In this jaundiced and damp architectural carapace, I see a combination between the body of the condemned and the legal powers to condemn? In the reflective floor, the shadows projected onto the walls, why here do I see The Mourners gone feral, and also a portrait of America?

*

As I write this, I check my Twitter stream, it convulses in rage and desperation. I refresh. Watch it unfurl. I turn it off. Wrapped as I am in anonymity, through the immeasurable veil of the internet, I attempt to imagine an adequate lamentation. I think of Anne Carson, in her translation of Euripides’ Grief Lessons: “Why does tragedy exist? Because you are full of rage. Why are you full of rage? Because you are full of grief.” I think of these figures whose task seems almost eternal, to mark a circle around some dead ruler, who I would as soon forget. It’s the procession of the mourners I’m interested in, in how their circling persists.