This Was No Mudd Club

Thomas Lawson

November 7, 2016

I made my first extended visit to New York in the summer of 1974. The intense heat and insistent sound of the streets were so much more penetrating than anything I had ever experienced in my native Scotland. I kept returning to 42nd Street, as if the key to the city’s secrets could be found on those blocks between Grand Central and Times Square. In those days the sidewalks pulsed with music, competing radio stations broadcasting from every storefront. One afternoon the music suddenly stopped, and serious male voices announced to the world that the President would be addressing the nation later that evening. In that moment everybody knew he was going to resign. The street hushed, traffic stopped. And then people began whooping and shouting, jumping and high-fiving; there was dancing in the streets.

Political theater in Britain was and remains firmly within the realm of politics, not street theater. Campaigns are short and often brutal, and nobody confuses them with any form of art. (The recent Brexit campaign stands out as an anomaly in that respect, with Boris Johnson and Nigel Farage performing as a particularly nasty vaudeville act.) But that hot afternoon on 42nd Street I learned that although the stakes may be higher in the US—leader of the free world, finger on the button, and all that—it can be difficult to distinguish the discourse of power from that of dance and comedy.

The next year, 1975, I moved permanently to New York with the idea of becoming an artist. I had many opinions and theories in mind, but I wanted regular exposure to the actual manifestations of what living artists were doing and showing, I knew I would never be able to forge my own path without it. In the city, a whole genealogy of Minimalisms and Post-Minimalisms focused my attention on the importance of material and scale. The critical investigations of Conceptualism, breaking down the hierarchies of representational thinking, engaged my intellect. But it was the non-linear imagism of certain kinds of performance and experimental theatre works—by the likes of Joan Jonas, Robert Wilson, and Mabou Mines—that really grabbed my imagination. And one thing these artists always referred to as an inspiration was the ancient Noh theatre of Japan.

A curtain opens and four musicians in black robes, holding their instruments, walk slowly across a bridge. About two-thirds of the way, each pauses and slightly adjusts his course. They enter the stage and take their positions in front of a stylized painting of a pine tree. Another group of men file in from the opposite side and kneel. The musicians— three drums and a wooden flute—begin a hypnotic score that will underpin the entire performance, a steady rhythm punctuated by varied yelps and a piercing, otherworldly flute. A stage hand appears behind the musicians and slowly walks to the front where he carefully lays out a brightly patterned kimono, center stage. The kneeling chorus begins to set the scene as an elaborately costumed and masked performer begins his deliberate entrance. He speaks.

I’ve never been to Japan, never been exposed to these theatre traditions. But then, this summer, Kanze Noh Theatre played the Lincoln Center Festival and I was able to see for myself. I was awestruck. This is a 700-year-old art form passed down through 26 generations of the same family, an art form that is utterly strange, but also completely familiar to anyone aware of avant-garde performance. Movement and action are so precisely choreographed that the performance borders on ritual. Yet there are such subtleties in gesture and variations in sound that there appears to be a layer of improvisation animating the whole.

The narratives are fairy tales, all supernatural beings and people of high rank, but they are nonetheless emotionally resonant depictions of loss, jealousy, hate. Each tells a story, but with poetic imagery rather than realist description or character-driven plot; image, gesture, sound, and silence carry the weight of exposition. In Aoi no Ue, a woman dying of an indefinable spiritual anguish is represented by a kimono carefully folded on the stage. Her husband’s jealous lover approaches to lament her own predicament and curse the dying wife, then reappears as an angry demon intent on killing her. The demon’s rage is stilled by the quiet will of a Buddhist monk, but the kimono remains, unmoving and unmoved. The action is marked by slight changes in the aspect of a mask, and is framed by slow diagonal movements, repetitive chants, and the beating of small drums. Yes, I saw echoes of Einstein on the Beach, and many other experimental performance works of the past three decades. But I also experienced a dreamlike evocation of deep emotional states brought to catharsis through the rigors of form rather than the shock of an unexpected narrative twist.

Two nights later, the Republican National Convention began in Cleveland, and I was reminded that political pundits like to describe these kinds of events as “Kabuki theatre” or “Kabuki dance,” by which they mean overly stage-managed set pieces arranged to deliver a predictable ending. It was certainly strange, a parade of the seemingly deranged expressing extreme levels of anger and fear in a repetitive way that seemed to deny each successive evening a dramatic arc, leading to a concluding diatribe that seemed to empty itself of content the longer it continued. Was this a kind of performance art?

The question has continued to resonate in the final months of the campaign. The three debates between Clinton and Trump certainly provided rich fodder for late-night comedians, each finding delight and horror in picking apart details of performance and elements of content. Alec Baldwin on Saturday Night Live captured the physicality of Trump’s performances, the pursed lips and narrowing eyes, the snorting and interrupting, the stalking and hulking. Bulked up in his over-sized suit and trademark hair, he appeared the very ogre. And, in response, Hillary practiced a minimalist restraint, rarely moving, presenting a tolerant smile which, with a slight change of aspect, turned to a flash of steel as she described him as a puppet.

Kabuki is a younger form than Noh, only 400 years old, and more secular. Although all performers in both forms are male, Kabuki was created by a group of women, and was intended to be more subversive of authority, and more popular in outreach, despite also working within strict formal limits. Both forms are highly conventional, using stylized gesture and intonation within repetitive structures, but leave room for the expression of individuality through the performance. The telling moment is vivid and ruthlessly concise, a dagger through the eye that fixes meaning deep in the emotions of the viewer.

The first journalist to use the idea of Kabuki to belittle a political performance was a right-wing hack agitating about the long, drawn-out peace process with Japan after World War II. All he saw was interminable slowness—no action, no drama. Now it is a cliché of political reporting, a shorthand to suggest that the fix is in, that the actors are reading from scripts that feign conflict before reaching a preordained conclusion.

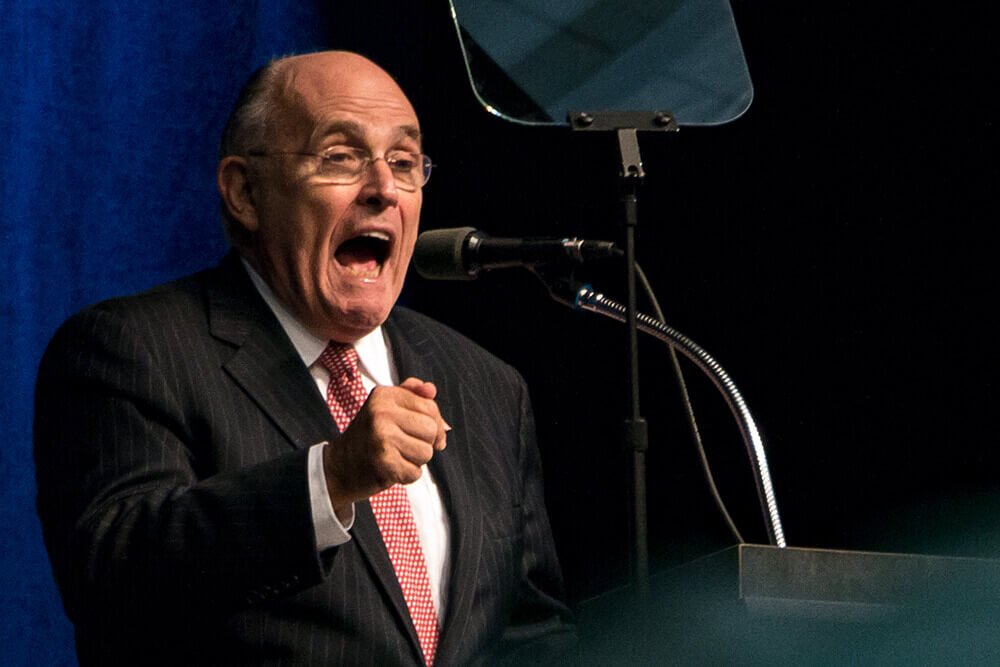

The first night of this year’s RNC was quite extraordinary, but for me the stand-out speech was Rudy Guiliani’s. Behind the podium the former Mayor of New York seemed strangely dimensionless: windmilling arms, a dark blue square of jacket, and, somehow attached to that, a mask with small eyes and small mouth, parted to reveal clenched teeth. During the speech this mask tilted back and forth, its expression morphing from contempt to rage to violently threatening. Its words were nonsensical, but had the poetry of bile. The speech ended with a scream—“Greatness!”—full of gleeful venom. Then the stage filled with colored smoke, and a giant shadow, instantly recognizable as Trump, was cast up against it.

Though this fall has brought a glut of memorable moments—bigly, grab them by the pussy, threats to sulk and refuse to accept the result of the election—that backlit, hulking entrance is what has stayed with me. Here he was, the great avatar of the real, the self-described voice of the people, here he was to introduce his wife. Suddenly I could hear the tumbling down of the tumbling down, I felt the earth move under my feet1: but this was no Mudd Club, it was just bad, schmaltzy showbiz.

- With apologies to Christopher Knowles, librettist for Einstein on the Beach, 1975.