In traffic on the bridge with Parker Posey, the sun had come out.

Ed Winstead

March 13, 2017

I have no idea what Parker Posey is really like, although I kind of do. In customs, and on the sidewalk outside of the airport, and in a van, and in a car, and, at a very particular sort of party, maybe, sure. But my thoughts have required adjusting, and then adjusting again, and again. I met Parker Posey in Istanbul, in June. In the intervening time people have kept asking me about her. And I say, well, she’s more or less like what you would imagine. But, on the other hand, shit, how could I possibly know that?

It was the day after my flight over, and I was wedged in the back of a black Lexus. Jason Rail, a hair and makeup guy, Parker Posey in the middle, and me. We were gliding down the Otoyol 1 towards the Bosphorus Bridge, aka the First Bridge, aka the 15 July Martyrs Bridge, and beyond it the European side of the city, on our way back from a panel Parker had done with the Turkish actress Serra Yilmaz for the Istanbul International Arts and Culture Festival. We made small talk for a bit. I asked her what it was like, people coming up to take pictures of her all the time, and she said she didn’t mind. Jason, who was Parker’s +1 for the festival, made a joke about who would play Parker in a movie adaptation of the book she’s been working on, a memoir-slash-recipe compendium-slash-life manual from the sound of it (on shelves this October).

We talked about how she does needlepoint on set, how this is a meditative thing for her. She was jealous of Mary-Louise Parker, who can count her stitches. She has an idea for a food truck. It’s in the book. Also a good recipe for Rice Krispies Treats. We eased to a stop; traffic. What was she reading? Meghan Daum, The Unspeakable. She chewed gum—she moved around a lot. I kept my elbows tight against my sides. And then we reached the bridge.

***

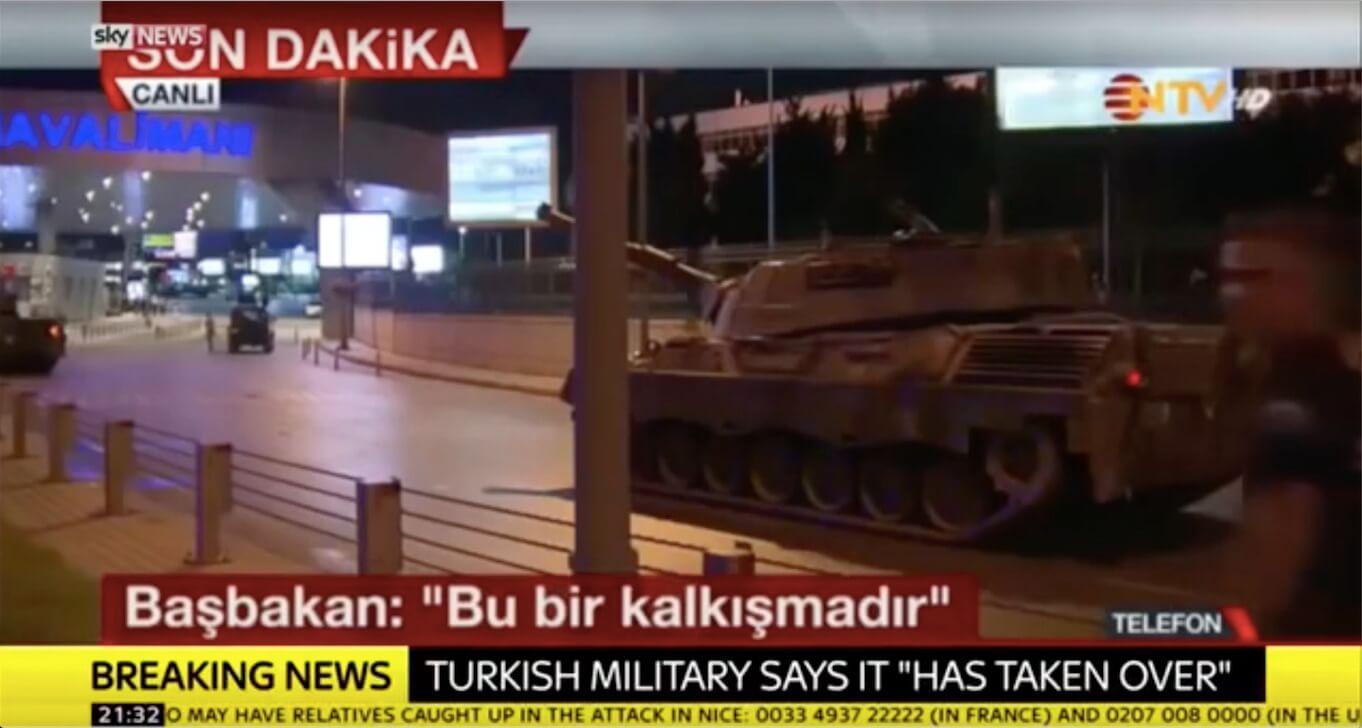

It was a month later, at my desk in an office in Manhattan, when I first saw that there was something going on in Turkey. A revolt of some kind, or a coup. I recognized the bridge on my laptop screen, the memory of the place still fresh. There were tanks plopped across it like lost, geometric shrubberies bounced from a wild truck’s bed—alien and conspicuous and familiar. The troops fired on the crowds. A dead man lay on the concrete, Turkish flag draped across his body. The crowds came back later and beat the troops. Somebody hacked off one of the soldiers’ heads. He lay on his back, his fatigue jacket ripped open. There was blood on the road. The white t-shirt he wore under it was absolutely spotless.

I felt myself grab reflexively at that image, jerk my arm out as if to save it from falling off a counter. Not literally. This was the impulse to make that tragedy my own. A bastardized, encephalitic empathy response; a sense of ownership wholly unearned. I was, I think, trying to backfill some meaning for myself. See, I’d tried to make arrangements to extend my stay so that I could visit the refugee camps, and speak with some of the people there. But I’d been invited on short notice, couldn’t get ahold of anyone who could help me while I was there and couldn’t afford to hang around longer. So I went, and I attended the Istanbul International Arts and Culture Festival, and it was all very lovely. There are nearly 400,000 Syrian refugees in Istanbul alone, but I could see no particular evidence of them.

In traffic on the bridge with Parker Posey, the sun had come out. I was wishing, if anything, that the traffic would get worse. I was having a good time. We crept over the Bosphorus toward Europe. I asked how Parker had come to do the audio book of Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique. “The producer, when they were thinking of actresses to read, said that I was one of the only ones who hadn’t done Maxim.” It took twice as long as she’d expected to record the book, which meant nearly two weeks. She said it was depressing, that particular idea of feminism and what it had become once released into the culture. It had been human, it had been equality. This polarity that happened, instead of openness… she trailed off.

Parker’s work has always struck me as being particularly, notably empathetic. Very identifiably herself (with a few jarring exceptions, like Blade: Trinity—I got a Hollywood gig that year, she said), she is nonetheless entirely who she’s intended to be. Doesn’t become a character so much as they become her. There’s a real desire, she told me, to connect through story. Which reminds me: when I asked her, on the topic of her book, what she liked to cook herself, she answered by way of something her mother used to make. She would grease up a plate, grate cheddar cheese on it, and stick that in the microwave for three or so minutes. What came out was a melted disc, not gooey but crisp. It was, she said, “like a giant Eucharist.” What a simile. What a story. Transubstantiation and all that.

We bounced around from one place to another in chartered vans or chauffeured cars, from fancy hotels to fancy dinners, champagne and candle light and a terrace or two, radiant under the moon. But you could have walked from the lux hotel where the festival participants stayed to the crumbling bricks of Tarlabasi, where migrants to the city have scratched out an existence for decades, in fifteen minutes.

And then I left. I distinctly remember the airport sign—block letters around the edge of a concrete awning, glowing blue. It’s unbelievably ugly, and as anachronistic a thing in that city as you can find. A busload of Chinese tourists just beat me pulling up. They piled through the sliding doors, a single unit, and I waited for them all instead of wedging myself in. I noticed that the plastic bins at the x-ray line for your carry-on and your jacket were wider, taller, a slightly softer type of plastic than the ones I was accustomed to. It’s funny how these little things, things you’d never notice you weren’t noticing back at home, are so key to the foreignness of a place.

A couple of weeks later, three guys with explosive vests and automatic rifles came through there and killed 45 people. I kept looking at the pictures, first at the blood and the glass and then past them; I kept trying to see where exactly those images were of, if I recognized the spot, the door. Was it the same door where I’d waited behind those tourists for my turn to go through the x-ray, watching them pantomime back and forth with the guard, unsure if their belts were supposed to come off? A shameful, solipsistic enterprise; I put a lot of time into it.

Parker told me that she didn’t understand how things could be so reckless at the moment. Your life goes by like that, she said. She said this emphatically, with the airy voice that everyone uses when speaking seriously in a car. Don’t you want to love? Be safe? Be stable? she asked. But then our time, like every other, is one of moral failure.

That night there was a party in the wood-paneled basement of the lux hotel; there was a decently famous DJ and everyone danced. It was very dark except for the occasional flash of a camera. People spilled out onto the patio, and they were all smoking and talking and drinking and dressed very well. Occasionally I saw Parker through the crowd. She was dancing. She would smile, and then be gone again. I badly wanted her to like me, and badly wanted her not to know that I badly wanted her to like me. I kept my distance. I resolved, anyway, to refer to her as Parker. Dress for the job that you want.

Meanwhile, the President of Turkey, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, purges his country of dissent—journalists, academics, judges, whomever. He forges a dictatorship for himself. Meanwhile, Aleppo lies in ruins. Meanwhile, more gunmen—New Year’s Eve, another attack, at a club under the shadow of that very same bridge.

I admire Parker Posey. She is a genius of empathy. What she is really like, I think, is whatever you need her to be. The genius of it: the being takes place entirely on your end, not on hers. You and I, we have our separate needs. That’s fine and makes no difference. I needed to be convinced again that stories can matter in a way directly opposite and proportional to the horrors we keep inventing for ourselves. Mind you, that’s not what she convinced me of; she’s not a shaman. She convinced me, instead, that she shared in that desire. And the better part of empathy is company, you know. The conviction that we are not alone.