Philip Johnson and the New American Fascism

Ian Volner

February 13, 2017

When it comes to Nazis, America just can’t seem to get it right.

In most Western nations, there have always been militant nationalists who—however grotesque—have nonetheless possessed a degree of flair. France had Maurice Barrès and Charles Maurras, the former a Symbolist poet and the latter a kind of a deranged romantic monarchist; Italy had the gallant Gabriele D'Annunzio, the inspired Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, and a whole flying squadron of Futurist artists and designers who erred monstrously when they allied themselves with Mussolini, but at least did so with some pennacchio. Even the Nazis themselves, brutish as most of them were, had Albert Speer. Hitler’s architect and head of munitions during the war, Speer was unredeemed either by his buildings or by his later political epiphanies, but he remains a subject of interest, an object lesson in how a man so civilized could descend into barbarism.

Contrast that, if you have the stomach, with our homegrown horrors. We’ve had Lawrence Dennis, the brown-shirted ‘30s poseur and author of The Coming American Fascism, who eventually backtracked when his pseudo-intellectualism landed him in serious legal trouble. We’ve had the midcentury American Nazi Party leader George Lincoln Rockwell, whose greatest political coup was pinning up a swastika in the living room of his suburban ranch house in Alexandria, Virginia, making him seem less like a menace than like the world’s worst sitcom dad. And, in more recent times, we’ve had the goat-faced David Duke, a walking “Just for Men” commercial who once managed to get himself kicked out of the Klu Klux Klan for stealing from the collection plate. Honestly, could anyone imagine a more insipid, gauche band of pudding-faced dilettantes?

Of course, in 2017, we have a whole new raft of revanchists, and some of them, terrifyingly, have ascended to very lofty positions. Their success reflects some long-deferred glory onto their fellow travelers past and present, who now look somewhat less hapless, if no less hideous, than they did before Steve Bannon was made our de facto shadow president. But Stephen Bannon? At this, the very moment of their triumph, America’s reactionaries have chosen for their idols yet another slate of artless boobs. Cannot a country so large and so rich produce one—just one!—isolationist, bigoted, economically innumerate lunatic who at least pretends to be high class, highbrow, or high fashion?

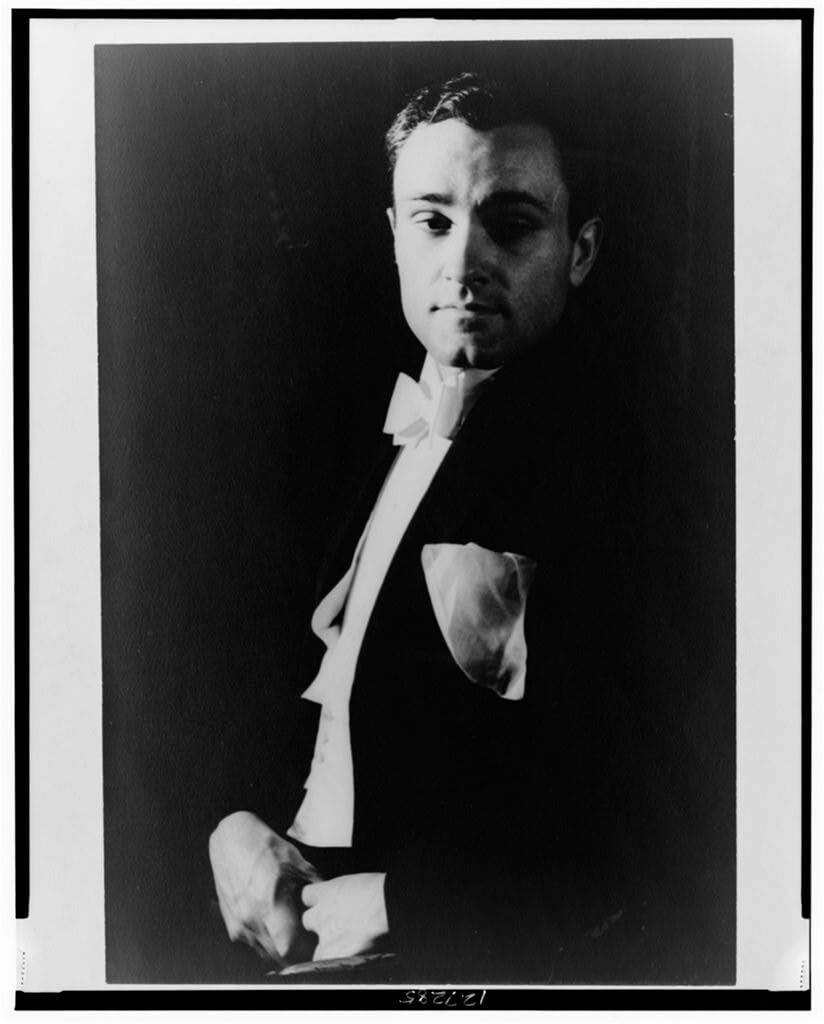

But we forget: America did produce one such person. America gave us Philip Johnson.

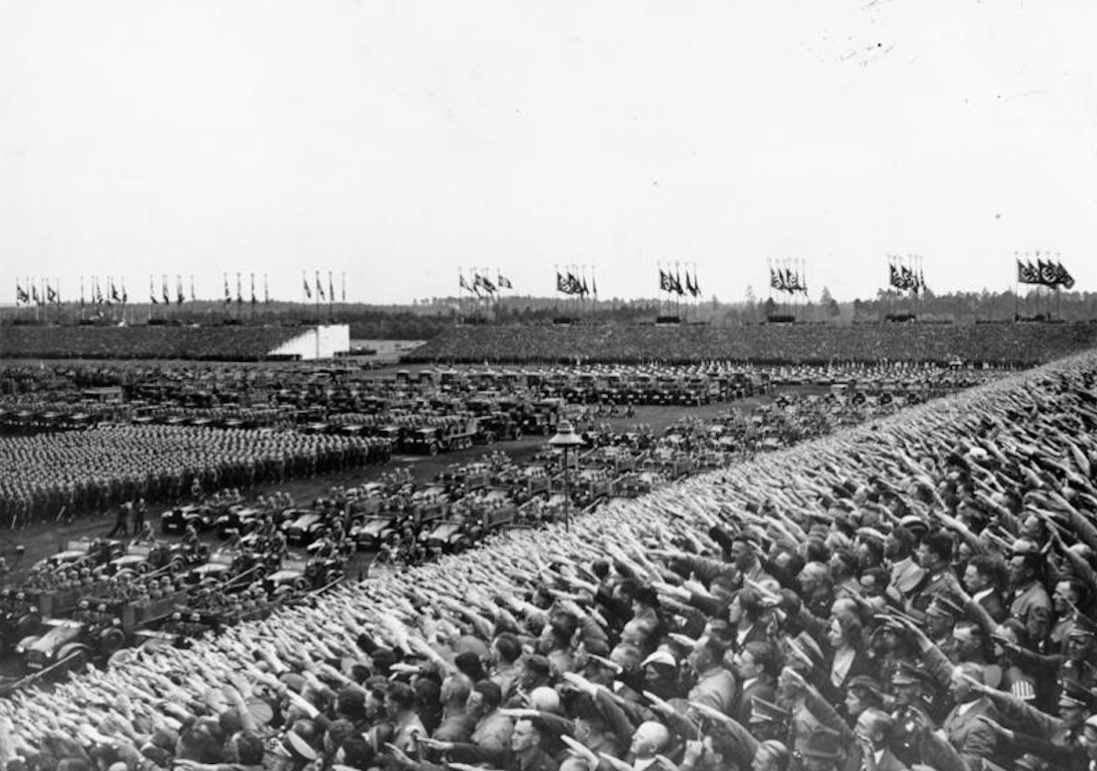

In what has long been the architecture world’s favorite bit of gossip (forgive us; we have so few), Johnson’s “inglorious detour,” as his biographer Franz Schulze once described it, saw the brilliant, wealthy young designer and critic make a visit to Germany, where he took a shine to those beautiful blonde boys marching neatly through the Nuremberg of the early ‘30s. Returning to the States, Johnson quit his post as the first curator of architecture at the Museum of Modern Art and set out to create a sort of NSDAP Lite in the American heartland. He tried first to enlist Huey Long—the combative Louisiana populist—and later Father Coughlin—the anti-Communist cleric and radio personality—to act as figurehead for this putative party. Attracting neither, he then attempted to enter local politics himself back in his native Ohio. When that too came to nothing, Johnson took off for another whirlwind tour of Europe just as German tanks rolled across the Polish frontier. “We saw Warsaw burn and Modlin being bombed,” he wrote at the time. “It was a stirring spectacle.” He added in passing, “There were not many Jews to be seen.”

The whole episode was as shameful as it was absurd. But it is also, at this late date, a somewhat tired subject. Rumors have circulated for years that someone, somewhere—perhaps one of the architects whom Johnson supported late in his career with cash and client introductions—is in possession of photos that implicate Johnson even more fully than the record presently indicates. As the theory goes, this person, or persons, used that evidence as a form of leverage. But it has now been twelve years since the “dean of American architecture,” as he came to be known, finally died at 93, so it seems unlikely it will show up now, if it ever existed at all. And, having lived so long, most of his allies and acolytes have also left the scene. There is a new biography in the works, and a new photographic survey of his career (the latter from Phaidon Press—full disclosure, I am writing it) but barring a great surprise, no more details are likely to appear which have not already been raked over endlessly by scholars and critics.

Yet in our present political moment, Johnson’s fascist flirtation makes an interesting case study. The most striking thing, for those overwhelmed by the sheer mediocrity of the “Alt-Right” and its camp followers, is how mediocre Johnson wasn’t: almost alone among his countrymen, Johnson carried off his noxious politics with style. Indeed, it was all about style.

Johnson had loped somewhat accidentally into design; a middling Harvard philosophy major, he fell in love with the Modernist buildings he saw while traveling Europe. Their jarring asymmetries, unadorned surfaces and pure abstract geometries captivated the impressionable young American, and he returned to the United States filled with talk of Mies and Le Corbusier, of the Dutch De Stijl and German Bauhaus. What he had missed, somehow, was that all of this architecture had a very specific social objective: to produce, on a mass scale, affordable housing and urban infrastructure for European cities devastated during the First World War. That was all very well and good for Philip, but he just liked the look of it. He liked it so much, in fact, that he gave it a name—the International Style—which he popularized through an exhibition of that title staged by him and historian Henry-Russel Hitchcock at MoMA in 1932.

Having reduced the political potency of Modernist architecture into an anodyne style, it should be somewhat less surprising that Johnson managed a similar trick with Nazism, blithely overlooking its moral ugliness in favor of the gloss: high leather boots, fluttering red flags, and of course Speer’s dramatically up-lit and starkly classical buildings. When the United States entered the Second World War, Johnson realized with a start that he had backed the wrong horse, and abandoned his former convictions as abruptly as he had taken them up. He managed the switch just in the nick, and was rehabilitated by MoMA and the Eastern Establishment in time to launch a wildly successful postwar career that saw him become the American design world’s foremost tastemaker.

His transgressions were by no means forgotten, however, and they returned at intervals to haunt him. By the early ‘80s, his most ardent critic in the press, the Village Voice’s Michael Sorkin, would regularly mention Johnson’s past by way of criticizing his mercurial, unprincipled approach to architecture; the art critic Robert Hughes, when he interviewed Speer towards the end of his life, wrote Johnson a wickedly teasing letter on Speer’s private stationery. (Speer, he reported, admired Johnson’s work. “I will try not put this story into circulation,” Hughes added, “or would you prefer a straight cash arrangement?”) Johnson’s contrition was real, and he did a number of projects for Jewish clients, including the state of Israel. But, on the whole, his remorse was rooted in the same aesthetic sensibility that had prompted his actions in the first place: he believed that politics were tacky, and beneath him. In all the long hours he’d spent talking fascism with Lawrence Dennis, he later said, he’d managed nothing more than to “piss away a whole lot of time.”

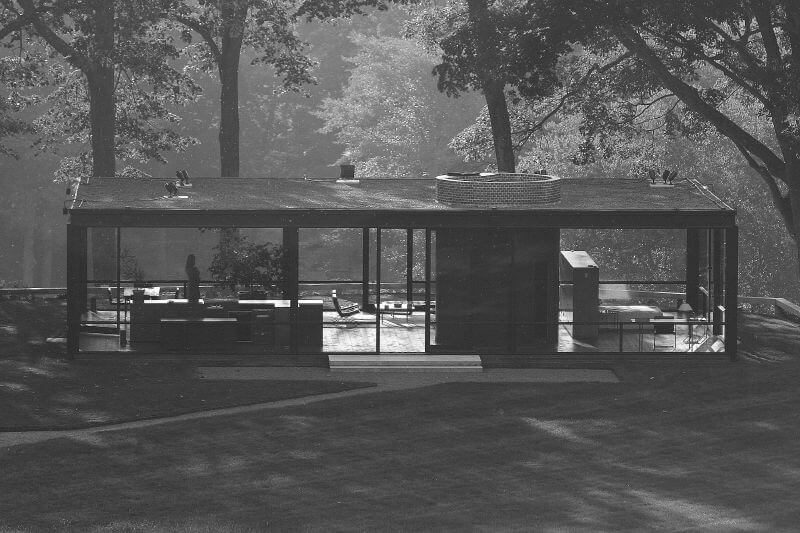

A staple of high society; the creator of extraordinary buildings, like his Glass House in New Canaan, CT; a great patron of the arts: Johnson’s curriculum vitae nearly makes up for the blah-ness that characterizes the rest of America’s fascist sympathizers. So, with that in mind—and recalling as well his belated efforts to right the wrongs of his fascist past—what would Johnson make, were he alive, of today’s illiberal chauvinists, whose star now seems so ascendant?

He might have objected to them as crude and distasteful—though not too loudly. Johnson himself designed buildings for the Trump Organization, including the re-cladding of the company’s Columbus Circle tower and their row of buildings on the West Side Highway. Johnson might, being gay, have objected to the Administration’s social conservatism—but he was only too happy to work for evangelicals, having designed the Crystal Cathedral in California for Hour of Power host Robert H. Schuller. (At any rate, one need look no further than the vile Milo Yiannopoulos to see how easily some homosexuals are still seduced by the erotics of power.) Johnson might have groused about their immigration policies—many of his contemporaries, including the brilliant structural engineer Fazlur Khan, were Muslims—or about their anti-feminism—his closest friends were all women, mostly of the liberated stripe—or about a hundred other things. But he almost certainly would not have. He would have kept mum, and remained as elegantly aloof as possible.

Johnson’s political complaisance was amply demonstrated in another, albeit much less virulent, conservative era, the 1980s, when he and his practice thrived amidst the country’s go-go development boom. Certainly it should be said that the Reagan Administration, and the Conservative movement that gave birth to it, provided a more congenial cultural atmosphere for the likes of Johnson, with its dash of Hollywood glam and such glittering wits as William F. Buckley. Modern American Conservatism was founded, in fact, to prevent other intellectuals from making the same mistake Johnson had: Buckley launched the flagship National Review after quitting the anti-semitic American Mercury, the very publication that Johnson had considered acquiring as his personal mouthpiece during his “bad” period. For a half a century, Buckley and his circle managed to hold a tenuous line against blood-and-soil ideology, keeping out the riff raff and ensuring that the right wing appeared “respectable.” Those days seem almost quaint in retrospect.

Today, of course, the less savory elements which had always stalked about mainstream Conservatism have stormed the citadels of power. Their much-reputed vulgarity notwithstanding, they could not have expected much resistance from Philip Johnson. Even now, as anti-intellectual as our new nativist extremists may appear, there is nothing to stop another artist or novelist or architect with Johnson’s grace, Johnson’s brain, and Johnson’s utter lack of scruple from going a step further, assuming the role of the movement’s in-house cultural doyenne—a smoothly flippant and telegenic spokesman, adding a touch of chic to the proceedings. Come to think of it, it’s probably only a matter of time.