Art and the Quality of Money

Carter Ratcliff

January 15, 2018

Money is sometimes easy to quantify. You just add up a column of figures. Sometimes it’s not so easy. To calculate the national debt, you’d have to mesh advanced mathematics with economics equally advanced. Easy or difficult, the quantification of money can be checked according to agreed-upon standards. Everything changes when we turn from quantities to qualities of money. It’s like turning from math to art—from the verifiable to the imaginary.

Think of money laundering, not the process but the idea of it, which follows from the prior idea that some money is dirty—not literally but figuratively. The dirt the launderers wash out is metaphorical. Though much economic theory still assumes that marketplace behavior is always a rational attempt to realize a measurable benefit, some purchases are made on a thoroughly irrational whim. Hence the phrase “mad money,” which implies that cash can be crazy; and the image of “money burning a hole in my pocket” suggests that an acquisitive itch can generate metaphorical heat. As quantifiable as it is, money is no less qualifiable, and this is nowhere clearer than in the art market.

Consider two recent sales, one real and the other make-believe. The first took place last November, when Leonardo da Vinci’s “Salvator Mundi” went on the block at Christie’s and fetched $450.3 million. In the second, a young painter’s canvas, on view at a gallery on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, went for $5,000—hardly anything in comparison to the price paid for the Leonardo. Both sales are art market transactions, and yet this similarity holds only so long as we see money as quantifiable. The moment we acknowledge money’s metaphorical qualities, the purchase of the Leonardo no longer looks like an art market transaction. And the $5,000 payment for the work of a young painter no longer has the look of an art market transaction. For this distinction to make sense, I must stipulate that the $5,000 painting was bought with no expectation of future gain. Our imaginary buyers bought out of love.

Talk of love may sound like a swerve into sentimentality, yet it echoes a hard-headed pamphleteer named J. Jocelyn. Active in 18th-centry England, he published a polemic favoring free trade policies that ran counter to the era’s conventional wisdom. Goods, money, and bullion should circulate throughout the world with little or no hindrance, said Jocelyn, prefacing his argument with these remarks:

Value is an Affection of the Mind, and signifies the Liking we have to any Thing, from a Principle of Reason: Love is an Affection like it, and sometimes accompanies it, but that generally proceeds from Passion. There are many Things we Love without Reason, but nothing we Value without [Reason], tho’ very often with a wrong one.

(“An Essay on Money and Bullion,” 1718)

Though Jocelyn’s syntax may be labyrinthine, his main point is clear: economic value is established by “Reason.” Love, by contrast, ignores all rational considerations. At work in the marketplace, “Reason” is the chief faculty of “economic man,” an abstraction that still stalks the sprawling fields of theory. Embryonic in Jocelyn’s tract, adolescent in the writings of Adam Smith and David Ricardo, “economic man” arrives at maturity in John Stuart Mill’s comments on the limits of economics:

It does not treat of the whole of man’s nature as modified by the social state, nor of the whole conduct of man in society. It is concerned with him solely as a being who desires to possess wealth and is capable of judging the comparative efficacy of means for obtaining that end.

(“On the Definition of Political Economy,” 1836)

The capacity for rational judgment is versatile. You could bring it to bear on anything from chess to billiards to the mysterious powder found at the scene of the crime. As rigid as a stick figure, “economic man” uses rationality for just one purpose: to increase profits of a kind that can be quantified. Buy low, sell high. Buy a mid-range Picasso for a few million in 2017 and sell it for twice the amount five or six years later. That would be impeccably rational, even if you allow for inflation’s effect on the value of the dollar.

But why spend $450 million for a canvas by Leonardo da Vinci that has been heavily restored and is seen as a great painting by almost no one? To flip it for a profit? Not likely. Was this, then, an irrational purchase—the work of “economic man” on a bad day? Or was the buyer of “Salvator Mundi” in love with it? I suppose Jocelyn’s “Passion” might have driven the bidding to a record level, though it’s hard to imagine anyone falling in love with a painting that is not only not great but, let’s face it, mediocre. The most plausible account of the $450-million price tag begins with the likelihood that the buyer was indeed rational, although in a way that economists find difficult to theorize.

At the time of the sale, the new owner was anonymous. After three weeks, the New York Times and other newspapers reported that “Salvator Mundi” had been purchased by Bader bin Abdullah bin Mohammed bin Farhan al-Saud, an obscure Saudi prince. Several days later, the Times presented new evidence suggesting that Prince Bader had acted as an agent for his friend, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman. The Saudi Embassy in Washington then announced that Prince Bader acted not for the Crown Prince but for Abu Dhabi’s Department of Culture and Tourism. Much about this transaction is murky at present and may well remain so. We can be certain, however, that the purchase was meant to establish a record. Previously, the top price for a work of art was the $300 million paid in 2015 for “Interchange,” a 1955 painting by Willem de Kooning.

The new owner of “Salvator Mundi” has won first place in a competition that has been going on since 1987, when the $83 million paid for Vincent van Gogh’s “Vase with Fifteen Sunflowers,” 1888, tripled the previous record and signaled that works of art had become trophies in a newly invigorated game of conspicuous consumption—as Thorstein Veblen called it in The Theory of the Leisure Class. When that book appeared, in 1899, Henry Clay Frick was jostling J. P. Morgan and other tycoons in the race for old master paintings. Though the tokens have changed—works by the old masters are scarce on current lists of record sales—the game of conspicuous consumption is the same as ever. Corporations pay immense sums for headquarters buildings they hope will be hailed as landmarks; likewise, those who drive up prices in the art market expect their overpayments to bring them landmark status of a socio-economic kind.

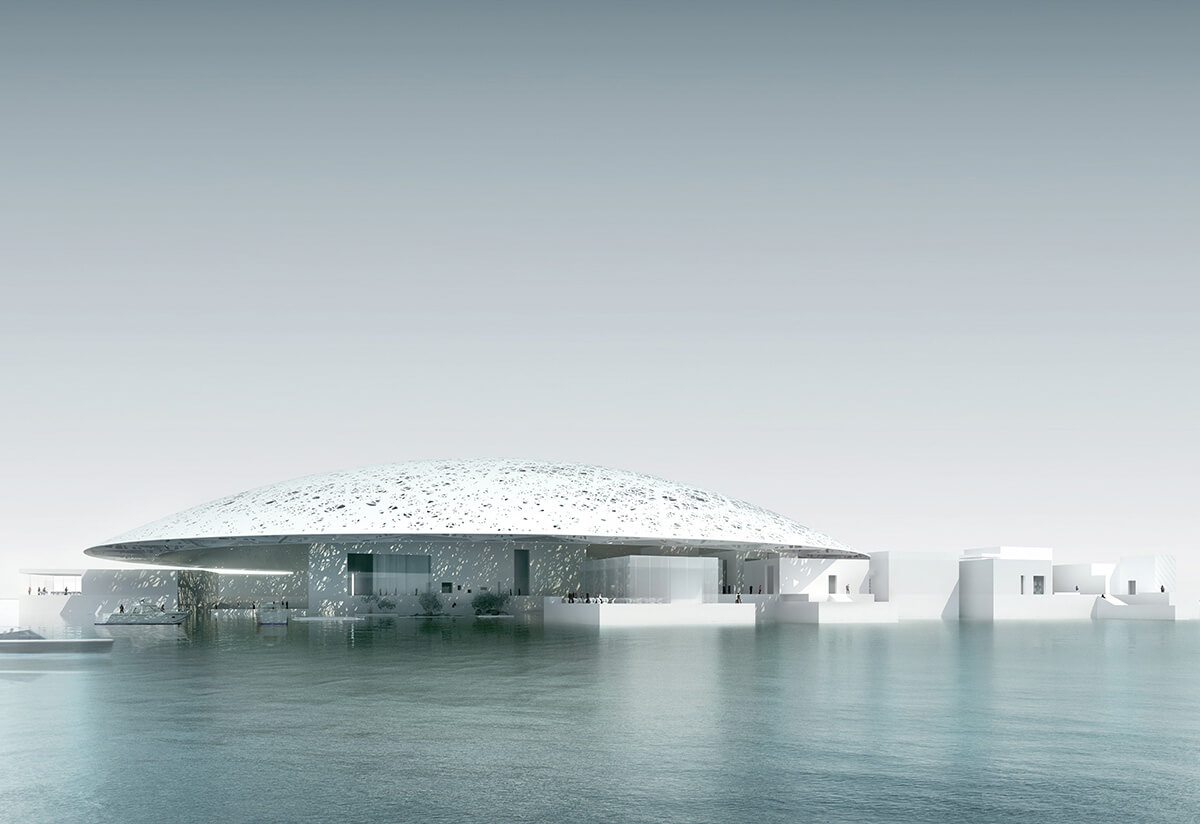

Though it has been open for only a few months, the Louvre Abu Dhabi already stands out among the world’s upscale tourist destinations. Its profile will rise still higher when “Salvator Mundi” takes its place in a collection that ranges from Benin bronzes and ancient Chinese gold masks to Ai Weiwei’s reprise of Tatlin’s 1920 “Model for Monument to the Third International” and an immense Jenny Holzer text written, literally, in stone.

Record prices prompt reactions so predictable that it’s rational to play the art-trophy game if one likes or, better yet, if one needs to be the target of abject awe and bitter envy and other dismal emotions. To become that sort of target is not to enjoy a quantifiable benefit. One can put a dollar figure on the profits from a hostile takeover but not on the public reaction to an auction-floor triumph.

Still, sales rankings produce something akin to quantifiability. To be in first place is measurably better than being in second place and being anywhere on the list of the top-ten art-trophy hunters is infinitely better than being nowhere on the list—assuming, again, that one defines victory in this game as a goal worth the expenditure of large amounts of money. If so, then the calculations that inspired the winning bid for Leonardo’s “Salvator Mundi” were those of “economic man” at his most swashbucklingly self-confident.

Though the Christie’s auctioneer was happy to accept bids of two to five million dollars for the painting, Prince Bader advanced the proceeding in much larger steps. The final bid of $30 million is remarkable because smaller amounts might have been sufficient, and if $5 or $10 million offers hadn’t sealed the deal, the buyer could have kept bidding. So the ultimate jump from $370 million to $400.3 million (the painting’s price before the addition of a buyer’s premium) was not merely extravagant. It was a gesture with an air of boastfulness, even arrogance, and those qualities now permeate the entire sum—every last dollar—paid for “Salvator Mundi.”

Sums that are high but set no records display other qualities. Say that a buyer pays a blue-chip price in the hope that his purchase will enhance his social status. Or he pays a premium for a work by a hot-newcomer price because he wants access to “a cool lifestyle,” to borrow a bit of patter from the sales pitches of certain art consultants. Money spent for purposes like these takes on a tinge of snobbishness mixed, perhaps, with anxiety about one’s place in the world.

The likelihood that the purchase of a work of art will bring a status boost or increase one’s coolness quotient cannot be precisely calculated. “Economic man” prefers safer bets. Nonetheless, the sort of acquisition we might call snobbish or aspirational has a crucial resemblance to a transaction that produces an easily reckoned profit: it is a means to an end. For better or for worse, most actions are self-interested. Yet we do some things for their own sakes; moreover, we possess some objects because we find them valuable in themselves. Ancient in origin, the idea that an action or an object can be inherently valuable took on a new salience under pressure from early modern science and technology.

Dazzled by Isaac Newton’s analysis of the physical world, Claude-Adrien Helvétius, the Marquis de Condorcet, and other luminaries of the Enlightenment tried to adapt his theorems to everyday life. Society would run with machine-like efficiency, said Condorcet, if it were redesigned according to Newtonian principles derived from the accurate observation of human behavior. Appalled by this mechanistic utopianism, William Blake took Newton as the model for Urizen, the allegorical figure of patriarchal Reason who appears in many of Blake’s poems and prophesies of the 1790s. Bent on reducing the universe to a system of means calibrated to ends, Urizen is that familiar personage, the instrumental thinker, raised to the scale of myth.

Though he was anything but Blakean in sensibility, Immanuel Kant shared the poet’s horror at the thought of a world composed only of opportunities for utilitarian calculation. In a world so conceived, even human beings would be treated as means to ends—and this, Kant believed, is the worst sin. If we are to realize our humanity, we must treat others as valuable in themselves.

Incessantly rethought by poets and philosophers of the Romantic period, Kant’s concept of the self took a sudden, evolutionary leap in Théophile Gautier’s preface to Mademoiselle de Maupin, a novel published in 1835. From that moment on, the inherently valuable person was poised to find a counterpart in the work of art valued for its own sake.

Exasperated by “utilitarian critics” who comb through books in search of solutions to social and political problems, Gautier insisted in that poets and painters and sculptors have but one proper goal: to create beauty. He did not mean beauty calculated to render our surroundings more pleasant, much less beauty laid on to make moral lessons more palatable, but, rather, beauty absolute and autonomous. From Gautier’s vision of beauty unencumbered by usefulness followed the notion of art for art’s sake and all the ideals of aesthetic purity that proliferated in the Parisian avant-garde of the mid-19th century, in the dreamy dogma of turn-of-the-century Symbolists, in the formalism of Roger Fry and Clement Greenberg, and so on.

Despite the differences between these doctrines, they all posit an affinity between an inherently valuable work of art and a human being as conceived by Kant. Both artwork and person deserve to be prized in and for and as themselves, not for the uses to which they can be put. And one might fall in love with either person or work of art.

Precisely what it means to fall in love with a work of art is impossible to say, in part because each case is different. In every instance, though, to love an artwork is to step out of the world populated by “economic man” and his latter-day descendants, who are not as reliably rational but just as intently focused on calculations of self-interest. To love an artwork is neither rational nor irrational; it is a response, imaginative and empathetic, to a presence in some sense comparable to one’s own.

In my fictional example, the price of the loved artwork is low, to provide a sharp contrast to the $450.3 million spent on “Salvator Mundi,” but it could of course be high. High or low, an expenditure made for love is the metaphorical equivalent of an embrace, and thus it imbues money with Jocelyn’s “Passion.” When money acquires that quality, its significance is no longer solely economic. That is why I said at the outset that the exchange of money for an artwork one loves need not be seen as a market transaction. It is an act of devotion, albeit secular.