Remake / Remodel

John Menick

January 28, 2020

The dead speak!

So exclaims the opening crawl of The Rise of Skywalker, the latest and last episode of the Star Wars trilogy of trilogies. The dead speak all the time in Star Wars, though lately they are chattier than usual, with all sorts of major and minor characters broadcasting back from the afterlife. By the trilogy’s end, Han is dead, and so are Luke and Leia, along with a recently resurrected Emperor. Even C-3PO has a near-death experience, one that turns him into a total amnesiac, a promising subplot the filmmakers are too unimaginative to develop. Chewie is assumed dead for a scene or two, before it is revealed that he survived an earlier explosion.

Meanwhile, Jedis have somehow acquired the ability to heal all wounds, thus helping Star Wars screenwriters escape any trap they may have set for themselves. Even if a character perishes with implied finality, like the Emperor at the end of the first trilogy, he or she is guaranteed to return, if only to capitalize on the audience’s nostalgia.

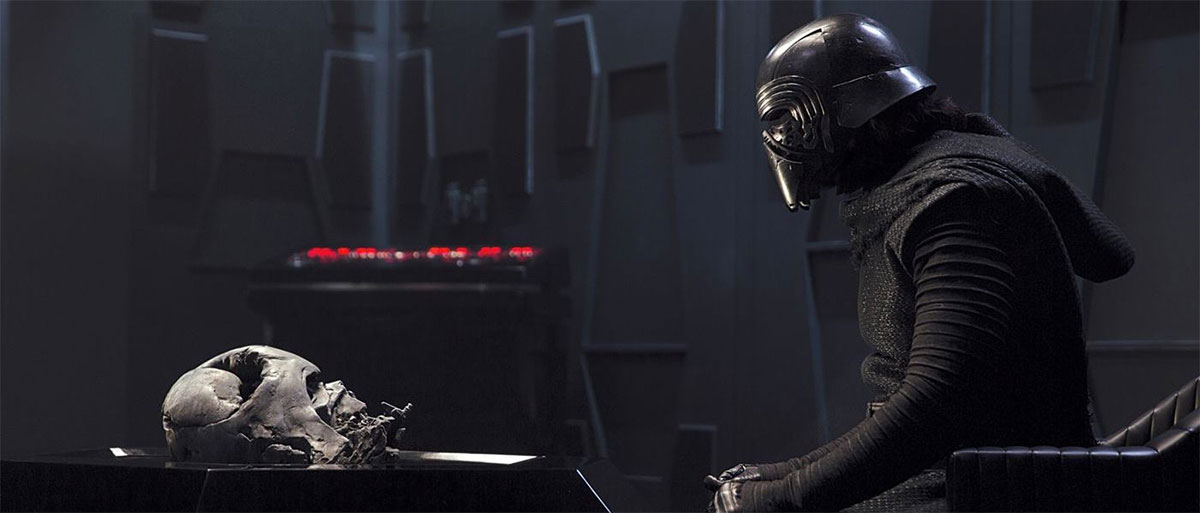

It's this seemingly bottomless nostalgia that has turned the Star Wars universe, after too many films, video games, books, and TV shows, into an outer space museum. Under J.J. Abrams’s direction, first-trilogy props are revered as fetishes and grounded Star Destroyers provide picturesque ruin porn. Even the film’s new villain, Kylo Ren, is little more than a Darth Vader superfan who stores his treasured Vader mask on a climate-controlled pedestal. It wasn’t always so backward looking, though. The first trilogy, made in the naïve glow of pre-franchise Hollywood, was mainly preoccupied with George Lucas’s cinematic crushes, borrowing freely from Kurosawa, fighter-pilot flics, Metropolis, and just about anything good the director ever watched.

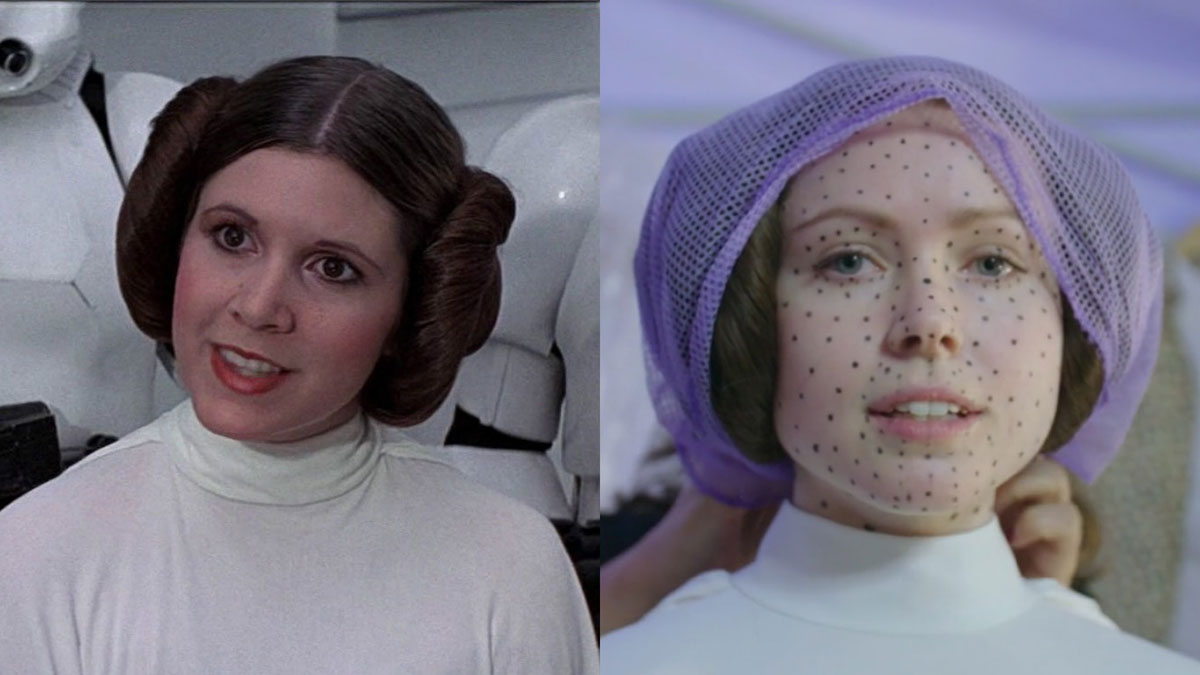

The latest films, like an aged Hollywood star, are only interested in themselves and their faded glory. They are desperate for a comeback, but no one really seems all that excited about the prospect: reviews are tepid to terrible, fans are often angry, and the actors look lost and underutilized. With billions of Disney dollars at stake, no one can switch the machine off. The franchise has become a death march, with fans annually summoned back to watch elderly Luke & Co. get serially lightsabered into retirement. It took the intervention of the real—Carrie Fisher’s 2016 fatal heart attack—to destabilize the inevitability of the whole morbid enterprise. But whatever problems her non-existence posed for the production were, like all Star Wars deaths, merely momentary. High-end CGI, leftover footage, and a few well-placed body doubles would guarantee that over the next several films dead General Organa continued to speak.

None of this franchised necrophilia is particular to Star Wars, of course. With nostalgia for fuel, Hollywood has been busy resurrecting past properties with serial ferocity, sometimes multiple times per generation. From Tron to Ghostbusters to Star Trek, the past is being strip-mined for any and all precious materials, marshalling every sci-fi narrative trope to the cause. Multiverses, time travel, dreamworlds, flashbacks, flashforwards, and transhumanism guarantee that all plots and characters can and must eternally return. With the need to keep franchises alive forever, the clean linearity of reboots, remakes, and sequels has given way to crossbred mutant forms of narrative repetition too complex to describe.

The first installment of the Star Wars sequel trilogy, 2015’s The Force Awakens, served simultaneously as a sequel to the first trilogy, a reboot of the entire series, and a beat-by-beat remake of Lucas’s 1977 A New Hope. In other franchises, audiences have seen reboots of reboots of remakes (2017’s Kong: Skull Island); sequel-reboots (2016’s Ghostbusters); prequel-reboots of remakes (2011’s The Thing); and sequels to prequel-reboots (2013’s Star Trek Into Darkness).

At the center of this repetition compulsion are flesh-and-blood actors, men and women who, unlike their onscreen ego-ideals, actually age, sag, get fat, and have the audacity to die. In the predigital world of one-off adult narratives, actors could age through a variety of leading roles, starting off as ingénues and rebels and ending up as grizzled grandparents. Along the way they could nip and tuck when needed. Botox and bleaching, rhinoplasties and rhytidectomies, boob jobs and butt jobs—entire industries were built to reverse, correct, and blot out the inevitable.

That was way back in the last century, however, during the antediluvian era of normal narrative closure. Now that true celebrity success is dependent on lasting through infinite Infinity Wars, aging is an even greater threat to the bottom line. Everyone knows that superheroes and elves don’t get old, and, therefore, neither should vastly compensated actors. Cinema has always been a symbolic bulwark against death, but today, with national economies built on precarity and instant obsolescence, onscreen eternity is more desirable than ever.

The true heroism of today’s superhero actor can be found in his or her eternal youth. When considering Infinity War’s abs and biceps, for example, one wouldn’t know that a good portion of the cast is north of 50. It doesn’t really matter if Robert Downey Jr. can remain 54-going-on-40 forever, though. He’ll eventually be replaced, just like every actor in every franchise is replaced. Celebrities are often compared to royalty, but in the end, they are closer to the workers on an assembly line: serialized, interchangeable, and just one wrong move away from unemployment.

The next stage, if bad sci-fi TV is correct, is computational immortality. Full body emulations, CGI reconstructions, maybe even brain scans come to life—anything is possible in dreamland. Why bother searching for a new Robert Downey Jr. when you can clone-tool his likeness for the next hundred years? Lola Visual Effects already “de-aged” Downey and his fellow cast members for the recent Avengers installment. Why not go all the way and replace him with an avatar powered by a down-market actor? The impoverished thespian can get his big break while Downey lives off the royalties without leaving his million-dollar windmill in the Hamptons. This is more or less what happened when a young Arnold Schwarzenegger appeared in 2009’s Terminator Salvation. The film used a plaster face mask of the actor made in the 1980s to create a retro digital Arnie. The real Schwarzenegger, meanwhile, was busy running the state of California.

This fall and winter, audiences witnessed several de-aged celebrities spread over three massively budgeted films: the aforementioned Rise of the Skywalker, Ang Lee’s Gemini Man and Martin Scorsese’s The Irishman. The Man-movies cost about $140 million each, almost equal to the annual budget of the National Endowment for the Arts, and Rise cost about as much as Lee and Scorsese’s films combined. With thousands of VFX shots per each film, de-aging constituted a large portion of both film’s overall cost and filmmaker anxiety. In various promotional interviews, Lee and Scorsese were frank about the difficulties in making four of the most recognizable actors in cinema—Will Smith, Al Pacino, Robert De Niro, and Joe Pesci—look like their younger selves. The release of The Irishman was delayed due to problems with the technology, and Lee’s film’s failure was in part due to the unconvincing nature of a Fresh Prince-era Smith. (A straight-to-video quality screenplay didn’t help either.)

After watching any of these films, it’s easy to see how de-aging will always fall short of its goal. As with overdone Botox or an unconvincing facelift, de-aging impedes expressivity, smoothing skin into a kind of computational death mask. Much of The Irishman’s promotional material championed the technology’s expressiveness, but whenever a de-aged face is at rest, something appears to go dead behind the eyes. De-aged actors don’t radiate youthfulness, but instead appear locked behind an algorithmically generated shell.

When we watch De Niro as a de-aged young man, we recognize his mole and his grimace, but his ears and nose remain those of his older self. Voice, too, is apparently ignored. When any de-aged character speaks, it’s with the gruff, aged voice of today’s actor, making all his younger iterations sound as if they paradoxically descended from the older man. The problem is especially noticeable when listening to Pacino, whose on-screen voice began, more than four decades ago, as a nearly falsetto nasal whine, before dropping to an easily caricatured baritone.

Below the neck, the effect is even more unsettling, with each actor’s body remaining arthritic and inelastic, hunched, lumbering through rooms, unable to stand or sit with any kind of grace. In one Irishman scene, De Niro’s character, de-aged to what might be his fifties, throws a gun into a river from the rocky shoreline. He can’t manage a fluid overhand throw, and instead throws the pistol with an underhand toss, betraying his inflexible shoulder.

Unlike the stage actor who performs in full view of the audience, the film actor’s body is purely notional, divided up between stunt people, body doubles, and stand-ins. (Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood is, in part, a brilliant enactment of this split between actor and double.) Movie audiences usually have no idea how tall an actor is, and camera sightlines often help obscure what would be obvious height differences on the stage. Nude scenes are usually shot with flattering body doubles, creating a disconnect between paparazzi beach photos and an actor's perceived cinematic physique.

The movies have always privileged face over body, making the close-up the central device of cinematic desire. The close-up was the movie star’s true medium—some stars, like Joan Crawford, lit their own. In Sunset Boulevard it’s the close-up that Norma Desmond thinks the news cameras are there to film. The close-up changed acting, creating new forms of expression for actors and audiences alike. In close-up, the slightest twitch, a curving of the mouth, the smallest teardrop, is enough to transfer the strongest emotions to millions. The close-up represents an intensification of cinematic emotion, an intensification that lives not so much through the actor’s body, but through his or her disembodied head.

De Niro has joked in interviews that de-aging offers the possibility of extending his career “another 30 years,” while many actors, including the late Robin Williams, have restricted the use of their images for decades after their deaths. The possibility of digital resurrection is very real and has been happening for some time now. In 2006’s Superman Returns, Marlon Brando appears posthumously as Superman’s father, Jor-El, his disembodied face projected onto a crystal screen. Brando’s face was reconstructed from unused footage shot during the original Superman films, augmented with computer graphics to manipulate his mouth in order to deliver the film’s new lines.

Ten years later, the Star Wars spin-off, Rogue One, featured not one, but two, dead actors: Peter Cushing, who died in 1994 of prostate cancer, and Carrie Fisher, who was both resurrected and de-aged. (A trick unnecessarily repeated in the most recent film for a brief flashback sequence.) Unlike Brando’s refracted face, Rogue One’s Cushing and Fisher are boldly displayed in full view of the audience, their barely convincing digital reconstructions inadvertently producing a grim kind of nostalgia. Perhaps realism travels asymptotically through the uncanny valley: always moving one step closer to an object permanently out of reach.

Not that Hollywood producers care. Realism is not their concern. Their business is desire. Desire for celebrity, sex, wealth, control, revenge, omniscience, immortality. Actors come and go, but the desire they embody remains. If actors become emulations—even imperfect ones—Hollywood shouldn’t be very worried. From a purely managerial perspective, the prospect of actor emulations is fantastic. Emulations don’t fight with the director. They don’t have drug problems. They definitely don’t go on strike.

Audiences will benefit, too. Finally, they will have their favorite James Bond forever, and Harrison Ford will always be as good as he was in Raiders of the Lost Ark. Realism may be asymptotic, but that means there is always room for improvement. The next Sean Connery will be even better than this season’s Sean Connery. If desire is insatiable, then so is our new cinematic future, with its striving for unattainable digital perfection. As Gemini Man’s Will Smith is rhetorically asked about his younger, better doppelganger: “Don’t you think your country deserves a perfect version of you?”