Secret Canon

Audrey Wollen

July 2, 2019

I have never read Rilke, not the elegies, not the sonnets, not the Letters to a Young anything. I thought for a while it was because I had never cared to, but in fact it is because I have never noticed his absence enough to amend it, as his canonization is so complete he has become practically atmospheric. He was the rare poet that received great acclaim during his lifetime, but his work also found fresh audiences decades later, in American New Age theologians, puffy airport philosophy, rote eulogies, and high school graduation presents. Mysticism is often a useful, if oblique, entryway into the mainstream.

So are public domain copyright laws. Now he is one of the most quoted poets of all time. It could be said that he unwittingly invented the entire self-help genre as we know it, since Letters to a Young Poet prefigures the drowsy poetics of contemporary betterment projects almost perfectly: No one can tell you how to be a writer, he says, in his text on how to be a writer. This is a contradiction that we all swim in now, stepping into the unfloored lake of tautology: The secret to life is thinking you have one, this insight will tell me what I already know, a list of rules that are made to be broken, love is love is love is love.

I want to make it clear that I haven’t been avoiding Rilke, personally, specifically. I consider myself a well-read person, at least for Los Angeles. I went to a liberal arts great books college for one year before I had a mental breakdown and was asked to leave, which is actually the sanest response possible to most great books, and I have read at least, say, 45 books by men. I don’t bristle when his name is spoken at an event, or appears on a stranger’s bookshelf. I socialize with poets, and I even speak a little German.

And yet his omission has been sustained, not by will or even neglect, but precisely by the impression that I might have read him without realizing, that prickling familiarity one feels with those who have been so presently absent, so overbearing in their vacancy. And it was this feeling, this unnoticed osmosis and claustrophobic disinterest, that motivated my decision to write about Rilke when I was asked to write about men.

I noticed that I didn’t care about Rilke when, purely by accident, I read three books about him in a row. This was startling, to say the least. You know those fantasies people have where all their favorite tv shows are actually part of a same masterminded universe, minute details coagulating into scabs of semi-coherent sitcom metaphysics? People watch for a single fictional pancake brand to be eaten across many different fictional breakfast tables in many different fictional American towns, a glimpse of synchronicity between otherwise disparate scenarios, hoarded scraps of profundity.

These books I read were the stories of women, but he appeared, insistently, in all of them. I felt like he was my odd, repetitive element. It felt like an unknown presence shadowing your walk home, until you realize they are the body ahead on the path. Can you be followed from in front? I was not seeking him out. I was just reading as I do, looking for the names of dead women. Literature, as we know it, is a vast plain of unmarked graves. If you are reading, you are grieving. I try to cut to the chase, follow the loss, carry some flowers. But in the middle of these women, in the green clearing of their lives, he reappeared.

*

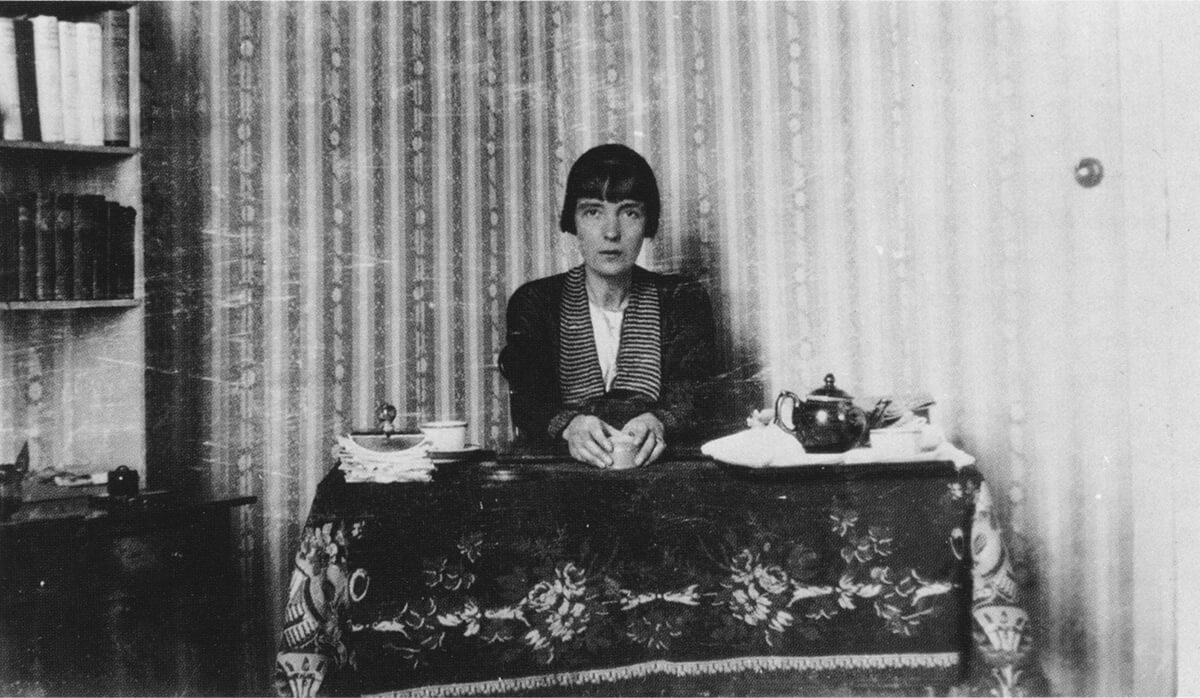

It started with Marina. I read her because I was reading Sontag. Susan Sontag loved Marina Tsvetaeva, and she didn’t love that many women writers, so I took note. It’s always interesting which women are admired by those women who seem to intellectually prefer men. Their prose couldn’t be more different. I always imagine Sontag as the character in the action movie that has to be called in from the van to diffuse the final bomb. Her language always clips the right wire. Her actions are quiet and precise, but in that precision they hold the most risk.

Tsvetaeva, on the other hand, writes like the bomb itself. She moves between vibrating containment and impersonal obliteration. Her rage is automatic, her scale is mythical. She was writing as a single mother in total poverty at the start of the Soviet Union, and she knew herself to be powerless. Much of her diaries are about bread, how to get it, which baby to feed first when you find it. But her poems are about her own divinity. In a love letter to the aging, unwell Rilke, she writes: “Who could speak of [one’s] sufferings without feeling inspired, which is to say, happy—to keep it from sounding like confession: bodies are bored with me… The mouth I have always felt as world: vaulted firmament, cave, ravine, depths. I have always translated the body into the soul.”

What a way to describe living, or maybe, dying. The line between the physical and the cosmic is a rhetorical distinction. Her proposal of death as a problem of translation is highlighted by the language troubles Rilke and Tsvetaeva bumped into in their correspondence: she writes in German, he writes in Russian. Neither are each other’s first language, both are gestures of affection for the other.

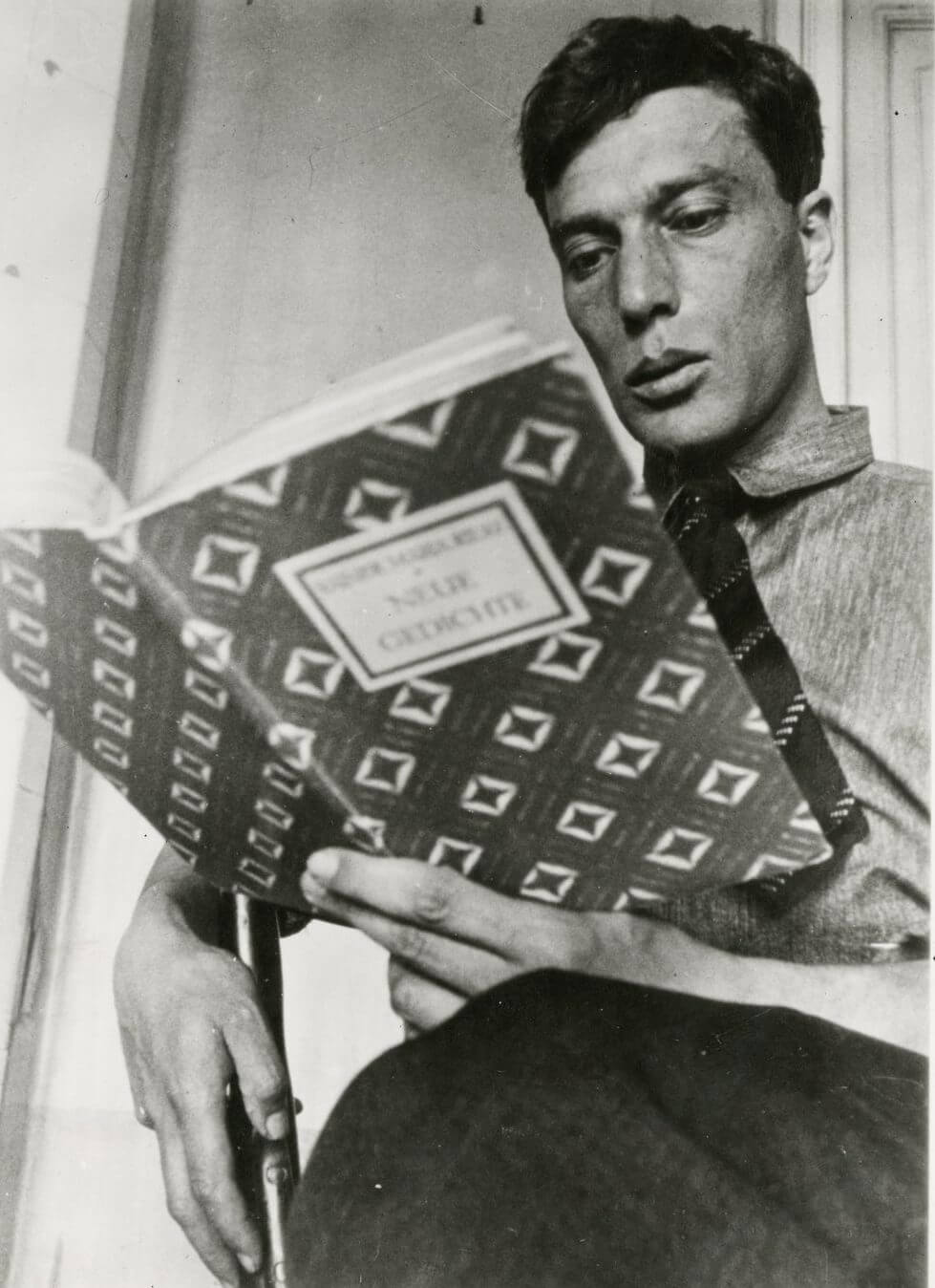

Tsvetaeva is obsessed with Rilke as he is dying, writing love letters in a three-way poetry orgy between her, him, and Boris Pasternak, who would later win the Nobel Prize for Doctor Zhivago. She is also in love with Boris, (in a very relatable move, she’s kind of in love with everyone, all the time), and both she and Boris idolize Rilke, or Boris idolizes her idolizing, or something, and Rilke, in turn, allows this idealization and often feeds it back, enfeebled but still reflective. It makes I Love Dick look positively restrained.

The three plan to meet, and this meeting is so anticipated that it is clear to the reader at its first mention that there is no way something so desired is ever going to be allowed to happen, especially not by the desiring parties. Luckily, Rilke dies. Tsvetaeva writes to him, after his death: “Dear one, now that you are dead there is no death.” It’s like he took a whole language with him. When a body burns, so does a dictionary.

She hangs herself in 1941, 20 years after these flushed letters. She was in exile at a Soviet work camp, many of her children had already died in horrible, horrible ways, she was alone and starving. He died of leukemia, in the arms of his doctor, at a resort in Switzerland. The story goes he had been ill for a while, but he went out for a walk with the famed beauty Nimet Eloui Bey and pricked himself on a rose. The wound never healed.

I write down in my notebook, from Tsvetaeva’s essay “On Love”: “I just want a humble, murderously simple thing: that a person be glad when I walk into the room.” I write down her note about women’s work, “Always stove, broom, money (none). Never any time. Not to sweep anymore—that is my kingdom of heaven.”

*

Rilke dies in the mountains of Switzerland, where he’s been convalescing from his indeterminate illness for the past five or six years and writing in a surge of unbelievable productivity. He moved into the Chateau de Muzot in 1921, where he completes the Duino Elegies and the Sonnets to Orpheus back to back. The same year, Katherine Mansfield moves in down the road, roughly a mile away, seeking a cure for her tuberculosis. They don’t know each other. He is 46, she is 33. She dies the next year, bursting a blood vessel in her lung after running up the stairs. But even though she is very sick, here she completes the books Bliss and Other Stories and The Garden Party, her two most famous works.

What’s in that town’s water supply? We need someone to do an astrological chart right now, for him, her, and the mountain. Is it the strange combination of post-war isolation, keen mortality, wide sky, clean snow? Does language flare before it is extinguished?

*

I read Mansfield because I was reading Ali Smith, and Ali Smith loves Mansfield and she almost only loves women writers, so I took note. It’s always interesting which women are admired by those women who seem to intellectually prefer women. Katherine Mansfield wrote about being a woman with sorrow and effervescence, in the same way Marina Tsvetaeva did. While Mansfield characters are usually ensconced in ruffled middle class desperation—getting dressed, throwing parties, wanting to die; the material opposite of Tsvetaeva—both refuse to let the world off the hook for what girlhood does to a person. The splitting of self, the doubled being and not-being that femininity necessitates, how words and images stutter over this multiplicity, built for a masculine singular.

From Bliss: “Beryl sat writing this letter at a little table in her room. In a way, of course, it was all perfectly true, but in another way, it was all the greatest rubbish and she didn’t believe a word of it. No, that wasn’t true. She felt all those things, but she didn’t really feel them like that.” From Tsvetaeva’s notes: “An exception for actresses, that is, for women, that is, for those who naturally play themselves, and for all those who, on reading me, have understood and arrived.”

*

The girl blurs under her sign, glimmering in the water’s reflection. Femininity smears so easily, but I can’t tell if that makes it more inclined to the universal or less so. In Paula Modersohn-Becker’s paintings, young daughters stare directly at the viewer: arch, thoughtful, unimpressed. The color swells into ruddy cheeks of knowingness. Their fate is clear, already, and they are disappointed. I read about her in Marie Darrieussecq’s curt biography, Being Here is Everything: The Life of Paula Modersohn Becker. I picked it up because I liked the girl on the cover. In other paintings, old peasant women lean forward, faces like stripped birch trees. Women nurse babies, and it’s hard to believe it’s the same subject matter of so many images before, so many Madonnas. The edges are soft but the shapes are compact. They are here, but a hundred years later, the paint still seems wet.

*

In 1906, Paula Modersohn-Becker is the first woman to paint a naked self-portrait. That we know of. She’s also the first to paint herself pregnant. She was married to a more famous painter, Otto Modersohn, and lived in the Worpswede artist colony. The story goes, she avoided consummating her marriage for fear of getting pregnant and having to give up painting. Her whole life she is torn between living alone in Paris, barely surviving, and returning to the safety of wifehood in Germany.

She goes back and forth and back and forth: to be a woman artist at the turn of the century, alone, with no money, or to be a wife in the countryside, at the turn of the century, with no creative practice. Both are impossible. She writes her dear friend Rilke, as she leaves home for Paris again, “I’m not Modersohn and I’m not Paula Becker anymore either. I am Me, and I hope to become Me more and more.” In a few months, she is forced to come home.

Her paintings still happen though, and that’s what they are like: events. They spring forward, like Katherine Mansfield dashing up the stairs. Her naked body smiles, glows. Eventually, as she turns thirty, Otto agrees to join her in Paris, instead of the other way around. Under the shadow of this generosity, she finally gets pregnant. They return to Germany. She writes to her friends in Paris obsessively about the 55 Cezannes on display there, and begs Rilke to send her a catalogue.

When she gives birth, it is a daughter, and something goes wrong. She is ordered to stay in bed to recover, until eighteen days later, when the family throws a small party for the baby, the mother. She puts her hair into braids, interlaced with flowers, stands up, and dies. While her paintings have finally received some of the recognition they deserve, she is mostly known as the inspiration for Rilke’s poem “Requiem for a Friend,” which is often quoted at funerals. She isn’t named.

*

His name isn’t even Rainer. It’s Renee. His first girlfriend, Lou Andreas-Salome, suggested he change it to sound more German. She was fifteen years older than him; he was 21, she 36. Andreas-Salome was that kind of woman who wrote countless books and accomplished so much and was a total phenomenon but is mostly known because she had dated Nietzsche, Freud, and Rilke, as well as a whole host of other people. She was one of the first woman psychoanalysts, and one of the first people to write about feminine sexuality, in a 1916 essay on the anal-erotic. Freud described her as the personification of female narcissism. He meant that as a compliment. In 1937, her library was raided, confiscated, and destroyed by the Gestapo for her allegiance to Jewish thinkers, pointedly Freud. She died suddenly of kidney failure a few days later.

*

I hold my women close, dead or not. Not-ness, of course, being our way of life. When I was asked to consider how men should be, I thought about how it must feel to not be not—a walking double negative. I can’t tell you how to be from this space of non-being. My boyfriend and I frequently get into arguments over my tendency to generalize. He loves specificity, context, nuance. I respect it, and I love those things too. But I usually speak in large categories, universal proclamations, talking like a manifesto even in gossip, in passing. I know stereotypes are stupid and harmful, for obvious reasons, but I’m willing to defend generalizations, as that’s all language seems like to me. A small, insufficient thing standing in for a big, complicated one.

I finally explained to him, when I talk about “men” and their power, their shortcomings, it is not for blindness to the subtleties of the individual or their circumstances. It is simply a practical solution for a lack of time. Do you want me to list every man who has done violence to me or my loved ones? I don’t know all their names. Trying to list them would be like recreating Borges’s map over a map—you know, that thing where they map the landscape so perfectly it just lays over it, doubling it. I can tell you my life in patriarchal harm, but it would take the length of my life over. I only have one.

*

I feel like I’m doing one of those negative space drawings in art class, tracing the air between the elbow, finding the blank edge. It is an impossible project, a feminist feeling. We spend a lot of time debating whether men should be written about, but I don’t know if “should” is the right verb. I don’t know if men can be written about, if it’s even a possibility. It’s simply not a sustainable model, as demonstrated by the impending end of the world. Every time you slice into the canon, girls rush out like ghosts. Lou, Paula, Katherine, Marina, so on and so on.

To write about them is an experiment in decentralized focus, fragmentation, spacious affection, floating hearsay, non-linear girl-history. It takes a tiny inkling of a tiny person in the vast cavern of history and tries to pull the plug on their aura of singular, masculine genius. I can only offer a method, and it isn’t even mine. Can the past one hundred years be written through the lives of the wives, girlfriends, mothers, daughters, workers, and spinsters? How different is the 20th century then? The 21st?

What would the history of painting be if pregnancy was always chosen, if childbirth was safe, if Paula Modersohn-Becker could have stayed in Paris? What is the history of writing if Tsvetaeva is read as Rilke is? Or Katherine Mansfield, like her friend, D.H. Lawrence? Lou Andreas-Salome like Lacan? And these, these are the already famous ones. These are the ones who got out, at least partially. They glimpsed a window, extended their hand.

This essay was originally presented at The Drawing Center as part of the series Bellwethers: The Culture of Controversy, a series of talks co-curated by Alison Gingeras and the editors of Affidavit, Kaitlin Phillips and Hunter Braithwaite.