Texts of Nothing

Kate Zambreno

July 28, 2020

[]

I am listening to a 1992 recording of Michael Silverblatt interviewing Kathy Acker. The two speakers aren’t aware of the fact that Acker will die five years later, at the age of fifty, but this fact now suspends over the recording. Acker is supposed to be promoting the book that’s been titled Portrait of an Eye, a collection of the three early mail-art serials that were self-published in the seventies semi-anonymously under the pseudonym The Black Tarantula and republished in various forms as her name became known, including this final form, an accomplishment of a midcareer artist who must now find some coherence or chronology in her origins, some attempt at a linear narrative, the fiction of a continuous and unified voice. To have one’s early texts reissued—to have this retrospective—is a form of resurrection of the fictions of the past, of past selves. There’s a ghostliness to that as well. Kathy Acker’s radio voice surprises me: she sounds like any New York intellectual. “Lit-er-a-ture,” she pronounces it. “I wasn’t interested in producing a piece of lit-er-a-ture,” she is saying.

[]

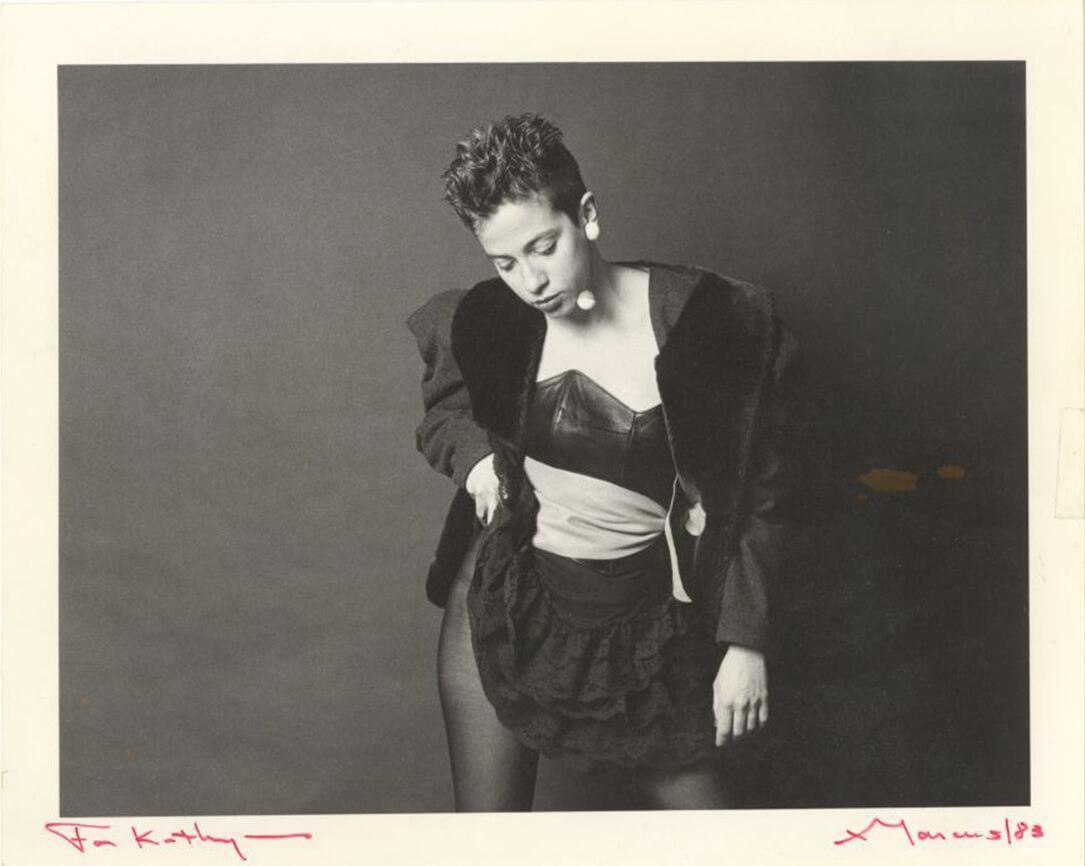

I am now supposed to speak of this book for the foreword of yet another reissue of this collection that has gone through many transformations. The persona of Kathy Acker has taken on even more attention and visibility in the past years, a biographical read often overdetermining the actual work’s compositional methods and aims toward decreation, fragmentation, and the nonlinear. This already was under way when Silverblatt was interviewing Acker. In England, she tells him, they manufactured an image of her—the punk iconoclast— and that made her career. Here in the U.S., the Grove Press covers, with her peroxided bust. The interviews she gave, the repetition of anecdotes—the origins of her intellectual coming of age, of her experimentations—the texts too, if one scans only for the fragments of autobiography, hidden like puzzle pieces, you get repetitions multiplied into myth: the isolated private school childhood, the mother’s suicide, the months spent when out of college working at the Times Square sex show while an outsider in the St. Marks poetry scene, an alienation that her biographer, Chris Kraus, sees as informing the fragmentation of her work, the squalid romance of being an artist in early seventies New York, all that survival energy.

[]

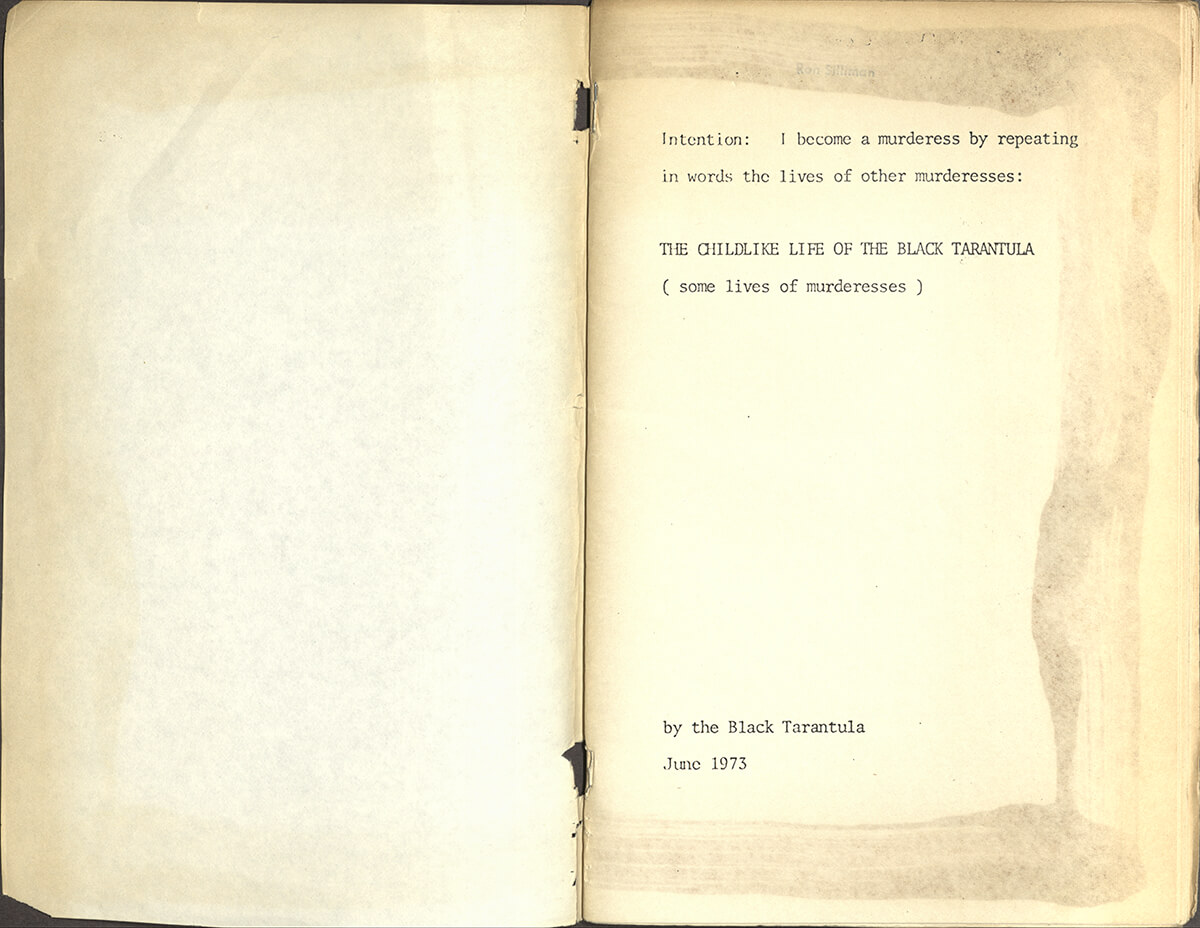

This is what has been told before. Kathy Acker began writing the first of The Black Tarantula texts, The Childlike Life of the Black Tarantula, in 1973, in her early twenties, having left the chaos of New York temporarily for Solana Beach, a town outside of San Diego, babysitting for David and Eleanor Antin, the poet and conceptual artist who were her earliest mentors. Borrowing from one of David Antin’s undergraduate writing prompts, Acker began taking out mass-market biographies of eighteenth-century murderesses from the UCSD library and copying them but changing them to first person so they seemed to be about her, collaging them with her own diary entries. “I figured, of all the people I could figure I’m not, I know I’ve never murdered anybody. At least not directly.” An obsession that has a tradition in Jean Genet and the surrealists’ obsession with the Papin sisters and Marguerite Duras’s fixation with the French crime reports, or fait divers. So she proceeds to juxtapose the “fake” autobiographical material with the “real” autobiographical material that jut out in frantic parentheticals. The first serial, “Some Lives of Murderesses,” begins: “Intention: I become a murderess by repeating in words the lives of other murderesses.”

[]

Acker saw these texts as experiments in first person, aided by her reading about schizophrenia (Laing, etc.) as she explained to poet Jackson Mac Low in a letter: “I do have this identity or self that’s full of holes, and I need other texts, I’m a totally reactive person.” What could the “I” be in language, could it dissolve into other “I’s,” could it be multiple? Could the I’s begin playing games with each other? By rewriting these pulp histories in the first person, with an anachronistically contemporary voice, she could play with her porous feelings of identification with mythic figures like the gender-bending Moll Cutpurse, seventeenth-century fence and pimp of the London underworld. She set herself constraints: no rewriting, no imagination or creativity (tenets of the bourgeois novel and cult of individuality), just tighten up the language, a certain number of pages a day. Calling herself The Black Tarantula, she prints up a booklet a month for six months, using the mailing list for Eleanor Antin’s mail-art postcard project 100 Boots (itself a photographic picaresque sending up of the American road trip after Kerouac, suggestive of soldiers returning from Vietnam, a squadron of boots posed in supermarket aisles, in fields with ducks, climbing single file over a car, connotations at times comic, fascist, pathetic).

[]

I try to imagine the thrill of what it was like to receive the first of The Black Tarantula booklets in the mail, her Byronic fugitive pieces, what it was like to read them then, the identity of the author unknown or hearsay, to try to make sense of the rushed confessionalism of the brutal isolation of childhood(s), the tonal shifts into picaresque tales, the layering of wild anachronistic language. This was the only time Acker’s sources were printed in the back. In the later installments, she begins drawing from literary texts, copying Violette Leduc’s schoolgirl novel Thérèse and Isabelle, overlaid with personal fantasies (“I move to San Francisco, I begin to copy my favorite pornography books and become the main person in each of them”). In another, she rewrites the autobiography of Yeats (a writer himself known for channeling and automatic writing). In the final chapter of The Childlike Life, Acker takes on as her alter ego the Marquis de Sade at Charenton (who changes genders), juxtaposed with abject scenes of an I voice from the clinic at Columbia Presbyterian, diagnosed with Pelvic Inflammatory Disease. Justine was also a durational experiment—the Marquis wrote it in two weeks while imprisoned, as a satire of the morally turgid novel, much as Acker here is reacting to the bourgeois expectations of surely still the most conservative art form, so aligned with the marketplace and moral values, her bad sentences mocking the expectation of beautiful ones, her overidentification devouring readerly expectation, her refusal of Aristotelian unity, of finding a “voice” as a writer as opposed to the unstable and multiple (“Why did I have to find my own voice and where was it?”).

[]

Not only are there explicit rants here regarding American involvement in Vietnam and the American government in this first text (“I won’t be jailed and given a lobotomy if I become an American solider instead of a murderess”; “The American government wants all poor people to die in the fastest way possible”), there’s something in these early experiments—their dissolution of boundaries and false truths—that speaks back to the hallucinatory instability and dread of Nixon-era America, seeming even more prescient now.

[]

As Acker has noted in interviews, there were other feminist conceptual artists making work in the early seventies about becoming somebody else, often switching genders— durational performances with which The Black Tarantula forms a ghostly and intentional correspondence—Eleanor Antin posing as many selves, Adrian Piper’s alter ego the Mythic Being, Joan Jonas’s hyperfemme Organic Honey masked personae. In his essay “Identity without the Person,” Giorgio Agamben traces back “persona” to the theater of the Stoics, the actor depicted holding his mask or the mask at a distance on a pedestal, a gap between the self and personae that Western concepts of identity has obliterated. “Point to the mask.” Acker, a trained classicist, looked often to the Greeks as well; the Greeks just repeated stories over and over. In her Black Tarantula femme fatale persona, Acker murdered her self over and over again.

[]

Back to the sotto voce of Silverblatt and Acker. As always, Acker brings up William Burroughs. She will only reference male writers in the interview, even schlocky ones, possibly to shore up that she is speaking back to this lineage she envisions herself in. Burroughs was interested in the gaps she is saying, in what happens between the cutups. The gaps. Of time, selves, fragments. I like thinking of these empty spaces in these early texts of Acker that seem so cluttered, so polyphonic. “La-cunae,” Michael Silverblatt says in response, which amuses and irritates me. “Yes,” she says. Lacunae—“an unfilled space or interval.” The missing pieces of a fragmented papyrus, a hole or lost section in a medieval manuscript. It reminds me of my favorite line in Anne Carson’s introduction to her Sappho translation: “Brackets are exciting.” A proposal for an essay I will never write about the kinship between Anne Carson and Kathy Acker—both come from the tradition of poetry, both classicists, both interested in fragmentation and decreation—except Anne Carson’s language and juxtapositions are elegant, Acker’s often self-consciously “bad writing,” including her copying of porn and best-selling hacks (in fact, it’s a war, she is telling Silverblatt here, a war against writing “properly, writing elegantly,” writing “lit-er-a-ture”).

[]

By the second serialized work, I Dreamt I Was a Nymphomaniac, her durational project becomes ritualized: the first half of 1974 occupied by free-form first person writing, then six months of producing the pamphlets, collaging pornography with diary entries. Her address list has now doubled, she’s become known, and she announces herself in the text: “My name is Kathy Acker. This story begins by me being totally bored.” She began repeating passages set amidst the existing tedium and repetition of pornography—a nymphomaniac repeats obsessively. A Sadean catalogue is also a series of repeated gestures, positions, pyramids. Sade can be a slog to get through. Acker’s Nymphomaniac is boring, too, but you’re not supposed to really read it, not in a linear, continuous way. This is what repetition does. It disrupts linearity, resists narrative. A text repeating becomes an experience of uncanniness—have I read that before—flipping back, scanning. Something that is no longer. Something that persists. Anne Carson performs this in Nox as well, a repetition of the same fragment over pages, so does Franz Kafka in his early diaries. Repetition is a form of ghost-making.

[]

There are similar composition techniques here as in Terry Riley’s drone-like In C (1964), its aleatory nature, the orchestration of loops repeated an arbitrary number of times. The name of Acker’s partner at the time, the music composer Peter Gordon, is repeated throughout Nymphomaniac, a sometimes hilarious Brechtian alienation effect (point to the mask or the name), to jolt a reader from emotional involvement. “Peter Gordon” changes genders, personas, in Sadean-lite chateaus and private school milieus, as well as sex-work settings that are both autobiographical and anecdotal reporting, the line blurry and impossible to know. “Peter Gordon” becomes Patty Hearst as a Symbionese Liberation Army (SLA) agent (Patty Hearst sending out communiqués as Tania at this time seems the exact sort of multiplicity at play here), and then, in following installments, appears in a history of Folsom prison, swapping in friends’ names for prisoners (including David Antin and his son, Blaise).

[]

What am I reading? This is what Acker is performing. What is a book? Is this a book? What makes a text legible or illegible? “You seem to be, in a Mallarmé sense, inventing the book,” Silverblatt is saying to her now. In a Mallarmé sense. “If you just open a book and say all a book is all these pages, anything can happen,” Acker responds. Mallarmé who wrote: “The pure work implies the disappearance of the poet as a speaker; he gives way to words.”

[]

I’ve been rereading Foucault’s 1969 essay “What Is an Author?” over and over, as if on loop. It strikes me that this is another correspondence for the flash origin of Kathy Acker’s oeuvre, even though Acker wouldn’t have read Foucault until 1976, when she meets Sylvère Lotringer, as she tells him in their conversation first collected in the Semiotext(e) book Hannibal Lecter, My Father (published in 1991, a year earlier than the Silverblatt conversation). Once she did, she tells Lotringer, the theory allowed her to continue these radical innovations in voice, collaging texts, rewriting literature. Both Foucault and Acker share an obsession with Artaud and Sade; their work both theorized a desire to disappear, to disintegrate into texts, but their photographed images through their fame often overdetermined this (also the twin leather jackets, the twin shaved heads, their stares).

[]

In his essay, Foucault quotes Beckett’s Stories and Texts for Nothing, a line that feels like it could come right out of Acker: “What matter who’s speaking, someone said what matter who’s speaking.” The essay reads like a noir. The disappearance of death of the author in the contemporary narrative versus the strategy of Scheherazade fending off death with further storytelling in Arabian Nights. Foucault writes: “Rather, we should reexamine the empty space left by the author’s disappearance.” An empty space where the author disappears—or the author is murdered. A gap.

[]

The last serialized narrative, or “novel,” The Adult Life of Toulouse Lautrec (first self-published in 1975) is something of a cross-dressing farce, where the gender-bending is at the level of naming, making us always aware we’re reading plays with language, where characters are just signified by names. Toulouse Lautrec, unbearably horny, worries she’s a “hideous monster,” a figure amidst a field of cocks. “I’m not even anonymous,” Toulouse Lautrec worries, a sly authorial commentary. There’s a character named Poirot out of Agatha Christie, investigating a murder mystery like slapstick noir. On the radio, Acker is saying it’s something of a class war for her: she takes on mystery and true crime and other “low-class genres,” because it makes her “giggle.” Gauguin is the local cleaning woman, boys work the brothel, Giannina the brothel waitress—like something out of Fellini’s Nights of Cabiria—wants to go to San Francisco to visit Ron Silliman (the real-life poet who Acker was crushing on, her books also functioning as gossip and infatuated correspondence, like a game she is playing). Juxtaposed throughout are anarchist histories, such as of Sophie Perovskaya who assassinated Alexander II of Russia, a short history of Paris in 1886 as it dovetailed with the Haymarket Massacre, porn starring a “Jackie Onassis,” and then an involved story line featuring a twenty-four-year-old James Dean and his apocryphal love affair with a nine-year-old Janis Joplin, juxtaposed with a stage reading of Rebel Without a Cause and a rant about Henry Kissinger, threaded into a history of the origins of American capitalism. Here, this last novel enters the pace and energy of the later, more canonical texts. If we insist on one singular Acker or Author. Foucault writes, “Rather, we should reexamine the empty space left by the author’s disappearance.” An empty space where the author disappears or the author is murdered.

A gap.

This essay introduces the new edition of Kathy Acker's Portrait of an Eye, available now from Grove Press.