Welcome to the Dollhouse

Natasha Stagg

June 18, 2019

1.

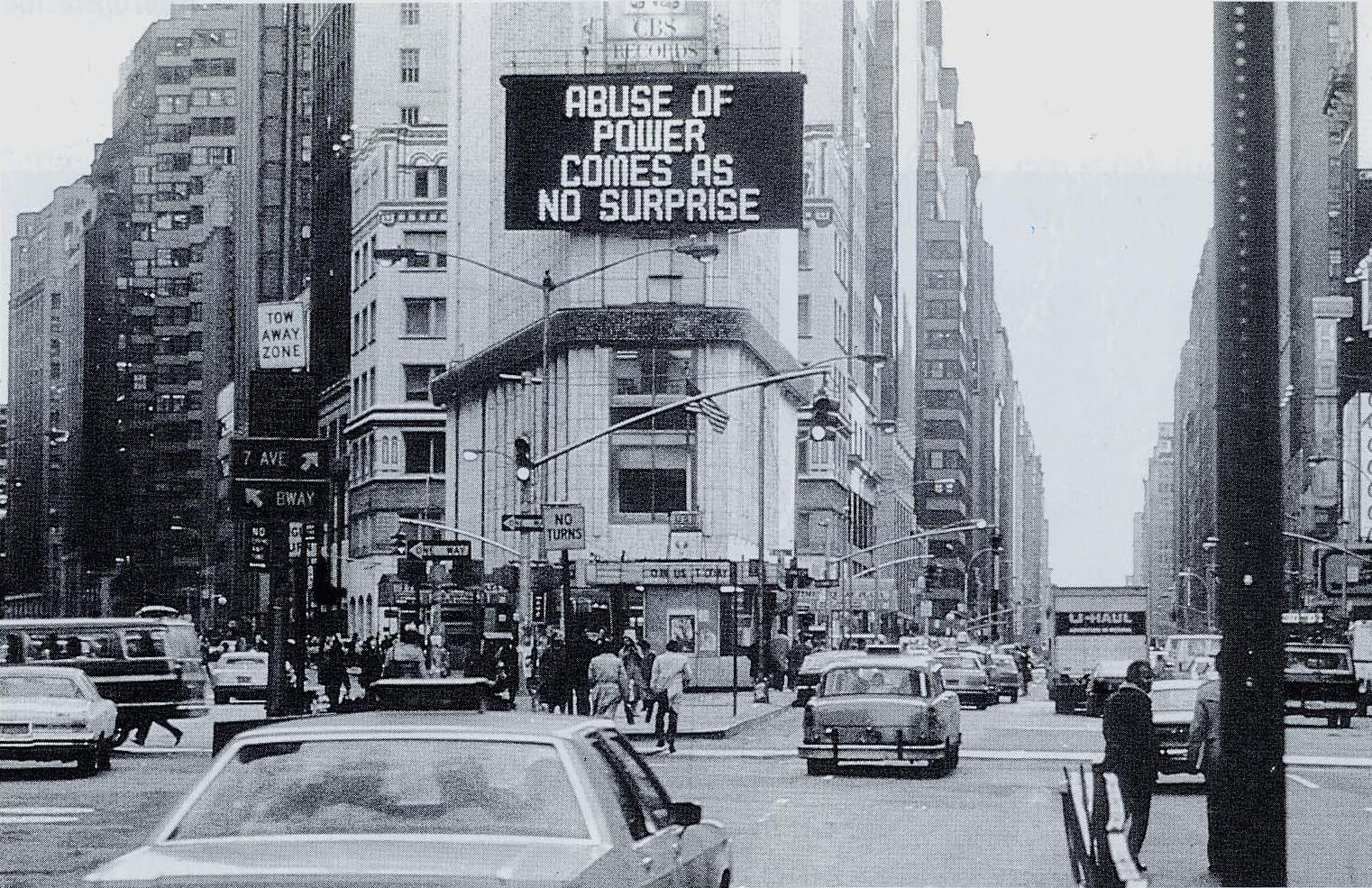

Speaking with a man who had been cancelled, I realized he wanted something from me. Validation, maybe, like another signature on the petition in his mind that says he’s not the crazy one. I know how that feels, but I don’t know exactly how it feels. It’s true that abuse of power should come as no surprise, and it is also true that with power comes a type of knowing. I do not know what it feels like to be a man, to be told you are privileged when you feel like nothing. I do not know what it is like to have my personal life shamed by my peers and colleagues. I guess I wouldn’t wish it on anyone, if I really thought about it. But, at the same time, I want some men to suffer. I would like for the trauma-bonded coalition formed since the #MeToo movement to stop their incessant whining. They can at least stop talking to me about it. “I’ve been slighted, too,” I said to this cancelled guy.

“Well, I’ll tell you what,” he responded, not in response. “If I had known that some women only go to those parties to further their careers, I wouldn’t have gone to them myself.”

2.

I have a friend, a publicist, who broke up with a man who said the #MeToo movement was a racist conspiracy to take down black men, mostly. He had been converted by Kanye West to Trumpism, unaware of the term. He was vocally incensed over the Brett Kavanaugh hearing, saying women had victimized him more than the other way around, and that this was another example of women getting away with something hurtful in the name of feminism.

“What a relief to be rid of him, right?” said the publicist, a smart person, about her ex. “Don’t let me do that again.”

“Isn’t it easy not to?” I asked.

She gave me a look, which was to remind me that, years ago, I had slept with this guy, too.

3.

I was having dinner with a group of friends and acquaintances when the cancelled publisher of an art magazine came up, and we all had to decide, privately, if we would still want to cancel him if his story was newly revealed now. “He was genuinely creepy,” said a stylist.

“It was bad behavior, enough to get fired over,” said a showroom director.

The stylist’s boyfriend, a retoucher, was confused.

“He was being manipulative to a lot of women,” I said. “But more importantly, it was an early event on the #MeToo timeline.”

In France, the movement is slightly different in scope, and called, if translated to English, “Out Your Pig.” Outing someone is generally considered violent, which maybe explains why so many French women, mostly movie stars and writers who had once been famous for their sex appeal, resisted movements like #MeToo and Time’s Up, calling them prohibitive to progress.

A group of gorgeous Parisian luminaries signed a petition stating that Out Your Pig and movements like it cause more harm than good. They called for protesting the protests, calling out call out culture. I sometimes write for French magazines and work for French brands, so I often get emails from France.

One email asked if I would consider interviewing one of the petition signers about the anniversary of her memoir. Another email asked if I wanted to interview a French director who appeared to be courting cancellation. Yet another email asked me to interview an American director who had loudly participated in the Time’s Up campaign. I declined each request, unsure of what I wanted to ask or hear from these people.

“Enough is enough, right?” said the retoucher, who was living in France at the time. His question was innocent. He had assumed we would all be protective of the men who didn’t rape or blackmail but were shamed nonetheless. The #MeToo movement had started innocently, too, an actionable antidote to the authority figures that endlessly fail us.

“See, it was one of the first ones to happen in the publishing sphere of the city,” I said. “And it was a revelation, then. All these women could talk freely about how weird it was that their boss was behaving a certain way, how weird it was that it seemed acceptable to become so personally involved in your employee’s social lives. All of these women had translated it to art-world-weird when really it felt, in its aftermath, infantilizing and rude, a violation of personal space.”

Even while I spoke, though, I thought of the publisher at a fashion magazine for which I once worked. No one seemed to mind his suggestive jokes and the hilarious memes he shared about getting shitfaced and desperate. He even dated a young intern, I think. I didn’t bring him up, though.

“Okay but does this man have to be cancelled for life?” asked the retoucher about the art publisher.

“He was fired, but he’s alive,” said the stylist.

“I’ve always anticipated that anyone could be fired for less,” I said. “Office politics are all about smear campaigns. It’s one of our only real rights as workers.”

The retoucher, a freelancer, was not convinced. I know, I know, I wanted to say. It will be all right in the end. Nothing will really change.

“Smear campaigns shouldn’t be okay, though,” said the publicist, looking away from me. I excused myself to have a cigarette before the check came.

4.

My registered-libertarian ex-boyfriend once explained the Trump thing to me as the first time any of these lower-class white people got to feel like a part of a subculture, which is an intoxicating experience no one should be deprived of. “I remember when I first discovered punk,” he said. “If I could relive that, I would.”

“But punk is mostly lower-class white people,” I said.

“Honestly, I’d rather work in the yard with some Trump guy from Queens than a Williamsburg hipster who just learned how to weld,” he said.

“But you live in Williamsburg and you started welding last year,” I said.

“Exactly.”

5.

My coworker and I were sitting in a park in SoHo, eating lunch on our break. “Should I be offended that this guy asked me to get him onto the Shitty Media Men list?” she asked.

A group of high school kids were sitting on the other benches in the park, eating ice cream. A short, bearded man with a British accent was telling them to gather ‘round. “Get the fuck over here,” he said, “so I don’t have to yell like an idiot.” They complied, getting closer and closer until I couldn’t hear anyone’s voices.

“It’s over now anyway,” I said to my friend. “The Shitty Media Men List is cancelled. And we were never invited to see it.”

“Well, this guy wants to be on it,” said my coworker. “He thinks it would help his career.”

“What does he do?”

“I think he’s an art handler,” she said, maybe forgetting what we were talking about.

I illegally lit a cigarette. “Maybe he should start a Shitty Women in Art list.”

The British bearded man and the hoard of children wearing soft tracksuits started to walk, as a group, out of the park, silently.

My coworker and I walked back to our office, in the other direction.

6.

I have a friend, a housewife, who has lived all over suburban Middle America. She called me the other day and said that her neighbor, a man, beat her up while her husband was out of town for work. The children were at school.

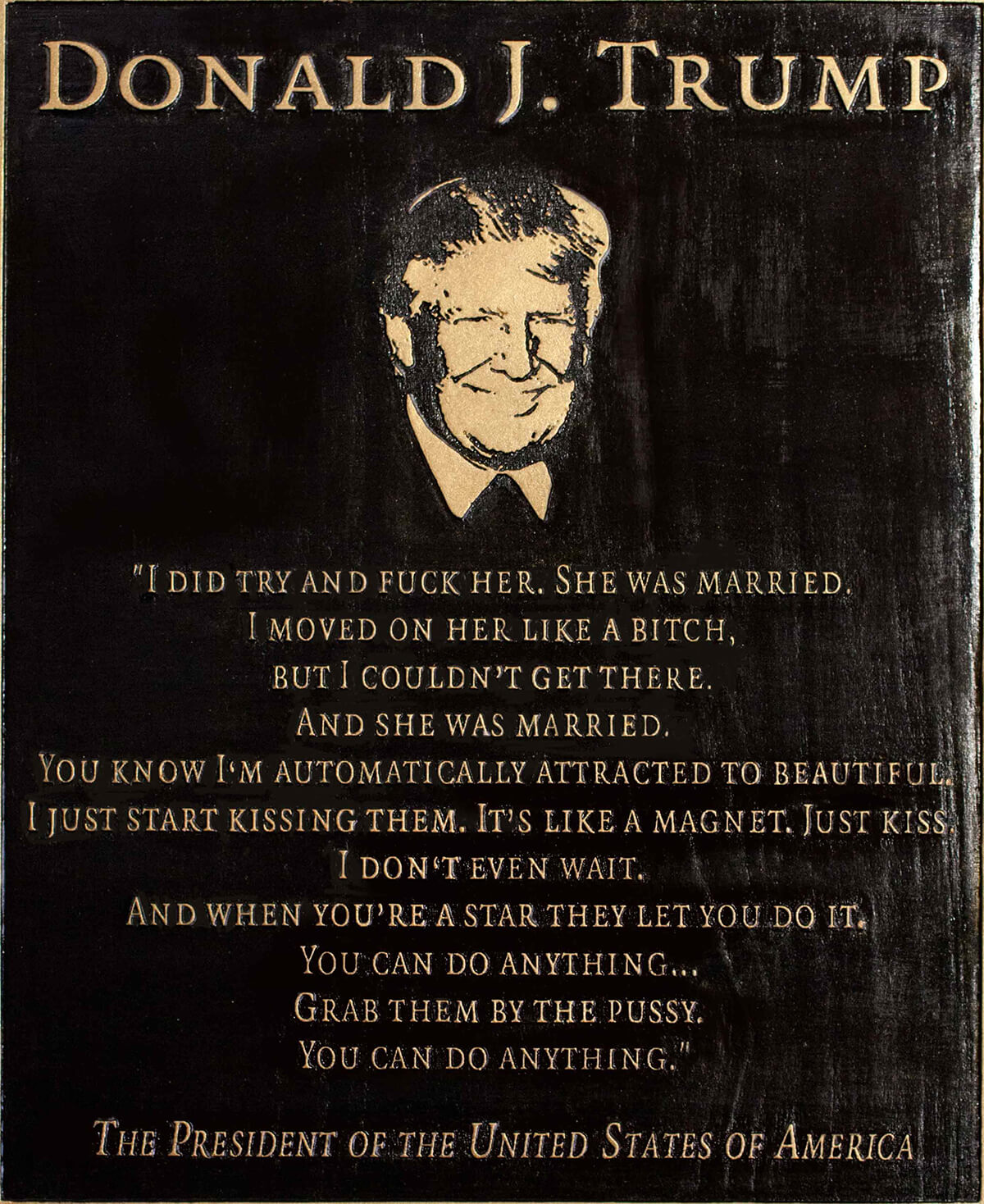

“Everyone out here voted for Trump,” she said, “and the thing is they voted for him because of the personal stuff. Of course all men say that pussy-grabbing kind of shit when they think no women are listening. I know that that wasn’t his platform and I shouldn’t pay that much attention to it because it was said in private, and look at what I say in private, but these guys out here where I live, they do pay attention to it. They fucking love it. They started paying attention when they heard he’d said that shit and they were like, hell yeah.”

She’d gotten into an argument with her neighbor over the president. Since she lived next door, she knew all of this guy’s extramarital secrets, so when things got heated, she had threatened to reveal them to everyone. That’s when he ran into her house through the backyard and choked her until she saw stars. She didn’t call the police because she didn’t want to start a bigger feud. When her husband came back from his work trip, he beat up the neighbor while she watched.

7.

Months after our only date, I received a paragraph-long text from a self-described Tim Allen fan at three in the morning. It ended with a cloying, “I think we had a nice time, right?”

Another text, from a different potential suitor, read: “I wanted you to know I think about you often.” It sounded like it would be said through clenched teeth. This one was from a guy who, on our first of two dates, complained about how much of his money his ex-wife spent on their kid.

A guy I slept with twice didn’t contact me again until he saw my book at the Strand. “Did you buy it?” I asked. He hadn’t, but he wanted me to know that he did buy a book, and that it was by another female author, one who was dead.

I had wanted leverage, and in some cases I had it. Men had started to act like scared animals, whimpering and then snapping. They had no way of knowing how hostile their very presence could feel to a woman who has been assaulted.

When I was asked to write something about cancel culture, I recoiled. I don’t want to say anything that isolates someone or hurts someone or dismisses someone, in theory. I say “in theory” because I know that it is impossible to create a universally inoffensive document.

I like the idea of creating all new sets of ideals with which to align, exploding a system of binaries. This was the dream of the anonymous public call out, which offers gradations to issues that demand a more complex response than a yes or no vote. I like that instead of running to a cop, we could participate in a conversation, offering one takedown at the risk of being taken down ourselves, by way of social media. That’s an idealistic view of something that relies on a system of sensationalism and exists within an algorithm, though.

Dreams of eliminating chauvinism by essaying about it were eventually dashed by a chorus of catfights in an echoing alley: screams circling a chamber, or a void, as we all like to say now. The problem, though, is that nothing is void when you say it online. As a society, we have had to learn that the only way to dodge cancellation is with distraction. Saturate with scandal.

8.

“Let me tell you about the way this thing played out,” a man I’d just met said. I was being told about some recent re-scandalization of Nabokov’s Lolita.

“On Twitter?” I asked, and then, to make sure he knew my unflinching stance, “I love Loli—”

“It started with an essay,” he interrupted, and then told me about the author of said essay, who was a woman he personally didn’t like.

There was another thing happening that was supposed to align people against a democratic presidential candidate because he’d said he loved Ulysses, which is apparently too highbrow for a president. So now I’ve not only seen someone describe the Joyce novel as a long-winded telling of a hetero white cuck farting into a toilet, but I’ve seen many people agree that this was an adequate summary of its 700 pages.

As one writer put it, in a takedown piece about takedown threads, “a dramatically reductive view of the past is very much in keeping with a particular kind of anti-intellectualist sentiment—the one that assumes, or pretends to assume, that no one actually likes ‘difficult’ books or movies or art, and that they are only saying they do in order to seem smart or trick someone into having sex with them.” People are naturally skeptical of things they do not understand, like books they have not read, or what it is like to have power.

People who didn’t read Ulysses before the advent of smartphones should be sad that they didn’t and probably never will. I’m happiest when I’m thinking about how I can always read a good book or watch a good movie again and remember the time when I first encountered it, which was so different.

Someone else was trying to convince me that a famous non-binary writer was shitty because their Twitter account sucked.

“Their books are brilliant,” I said.

“I’ve never read one,” he said.

“In high school, they meant so much to me.”

“We can’t always trust the opinions of people we used to love in high school,” he countered.

“Reading a novel is not listening to a person’s opinion,” I said, my voice shaking.

He told me a story about a Ukrainian artist who did not understand why Martin Luther King Jr. wasn’t cancelled posthumously after it was revealed that he had cheated on his wife. “It just goes to show you that context is everything,” he said.

“I think that proves my point, actually,” I said.

“I didn’t think we were proving points,” he said.

9.

On an old episode of 90 Day Fiancé: The Couples Tell All, an American man who is thirty-nine years older than his teenage Filipino bride says, “I know it must be hard for American women to understand this.” As I watched, the smirk on his face sent me into a rage that was purely emotional. The age of consent differs from country to country and state to state, which really tells us that our understanding of consent as a concept is fluid.

Age is fluid too, and yet it is difficult to see outside of our own fixed ages. As a young woman, I was involved in an affair. The most exciting part was that we would have to sneak around, in hotel rooms, on secret trips. It was difficult for me to empathize with the unsuspecting wife, who was older than both of us, and who surely at some point could never imagine herself as the age she was, in the situation she was in.

The other woman is a category usually relegated to younger women, and I was ecstatic to be young. One day, I thought, I will be old, and then I will be cheated on. It was my justification for acting erratically back then, even if someone had to suffer for my indiscretions. I was easily seduced by an unattainable man with worldly connections.

When I got older, a man cheated on me with a younger woman. I had never really thought it could happen to me, it turns out, because the information shocked me. The man had easily seduced this younger woman by impressing upon her that he was unattainable and had worldly connections.

My initial reaction was panic. My age had become the other one: old, not young. My next response was anger. I wished I could have revenge without having to orchestrate it. If only this type of behavior was unauthorized. Coincidentally, immediately following the revelation of this affair, the man’s boss was cancelled. Maybe I could just wait and see what happened. The next thing that happened was that he quit his job to become a ghostwriter and stopped all of his social media accounts. I never heard from him again.

Now that I have some distance, I can see that if I had publicly shamed this person I would have been a hypocrite in some ways. Not to say that my actions at one age are what must determine my convictions at another. What I mean is that a power imbalance is one of the most commonplace aphrodisiacs. Far be it from me to deprive anyone of a little fun, even at the expense of others, even at the expense of me.

10.

Another story: A few years ago, a man I thought I was in love with dumped me. I was taken off guard when he told me, mid-coitus in his Bel Air basement, that it wasn’t going to work out between the two of us. He said it matter-of-factly, though, as if I was obviously going to agree, maybe ecstatically—like a verbal confirmation of our shared detachment would intensify our intercourse.

He was surprised when I started to get upset, and maybe more surprised when I didn’t want him to stop fucking me. It was the night before he was to drive me to the airport so I could fly back home. I couldn’t sleep, though, and didn’t want to talk to him after that, so I asked if I could watch a movie on his laptop while he dozed off next to me.

I wanted to feel like at least I had New York, like I was going back to something wonderful, so I watched Woody Allen’s Manhattan. Nearing the end, I silently cried—because I was in bed with a man who didn’t love me but also because I loved Manhattan, the city and the movie and the memory of the first time I saw each.

I loved Woody Allen for making this thing for me to return to. At the same time, I could imagine that it would be painful to watch this if I was someone else: someone related to or married to or an ex of Woody’s, for example. Also if I was someone who was manipulated by an older man or left for a much younger woman and felt stunted by either experience. I could understand why every movie could be a bad time for someone.

I could even understand why people who had no citable experiences pertaining to this narrative felt oppressed by the cult of Woody Allen and his legacy. Anything so influential becomes an artifact consisting of its elements and their historical aftereffects. Everything exposed is eventually stale.

Watching Manhattan at that time put me in some kind of reverie, though. Even then, I vaguely knew that the man sleeping next to me would always be another thing to return to in future moments of despair, a memory of a meaningful time.

I would later realize that what I had mistaken for love was actually an emotional attachment to an earlier experience with another movie, anyway—one in which this guy was an actor. I had been dating the grown-up version of my childhood crush. What I mean is that he co-starred, as a fourteen-year-old, in a movie I first watched when I was fourteen years old, and I’d been in love with him ever since.

In Welcome to the Dollhouse, the bully character tells the nerd character that he’s going to rape her after school. She shows up, afraid but also eager for a diversion from her miserably typical suburban childhood. She tries to impress the bully, who is appalled by her lack of awareness, but touched, too, by someone displaying eager interest in him. I identified with the nerd at that age, having been thrown into a trite suburban landscape and desperate for a violent awakening. Later, I moved out of the suburbs. My first year in New York, I met Brendan, the actor who played the bully. By Christmas, I was staying with him in LA.

After I finished watching Manhattan, I closed the laptop and tried to sleep. The sun curled down the valley and bounced off the pool outside, sparkling ostentatiously until Brendan finally woke up. We drove through Bel Air’s green hills and wrought iron gates, the entrance flanked by faux Spanish monuments, pillars to a type of design that meant something else a long time ago. We stopped to buy three packs of cigarettes because they were cheaper in California. I cried myself to sleep on the plane.

I realized, after months of feeling devastated by the breakup, that my crush was always on the bully character Brendan played, not Brendan himself. I still can’t really tell the difference sometimes, though. Even his Staten Island accent was put on, an exaggerated version of the one he’d had to neutralize when he started acting as a teen.

Anyway, during our short relationship, my fantasy was played out in full. I was the uncool nobody, harboring feelings for an early representation of deviance in my coming-of-age: the classic tough exterior that gives way to a fragile ego. He was out of my league, but worried about being washed up, and captivated by my infatuation. I was ecstatic to be on a date with a facsimile of my dream guy and he was entertained by how nervous I was on our dates, reliving a type of stardom. We took advantage of one other. Although the dynamic was exciting to me and to him for very different reasons, all of those reasons were on the table from that start. There were times when the way he treated me didn’t seem fair and I was upset by the imbalance. There were other times when I wished he were treating me unfairly, since that more closely resembled the character I was initially attracted to.

Brendan didn’t love it when people asked him to say his pivotal line from Welcome to the Dollhouse, and understandably. Ever since he had uttered, at fourteen, “I’m gonna rape you, three o’clock, be there,” he’d been typecast as a psychopath, even though his use of the word “rape” was the naïve proposition of a sensitive portrait of lower class insecurity, a hopeless kid who resorts to empty threats. The line has had to age into an atmosphere where wordings are more closely watched. Perhaps, in a post-Trump context, the story of an adolescent performance of masculinity meeting a misguided rape fantasy isn’t as heart-warming.

Still, it will always resonate with me, since I am a product of my experiences. I will always have the movie, the memory of the first time I saw the movie, a casual friendship with the lead male actor from the movie, and the memory of the first time he whispered in my ear, “I’m gonna rape you, three o’clock, be there.” I feel sorry for anyone who doesn’t.

This essay was originally presented at The Drawing Center as part of the series Bellwethers: The Culture of Controversy, a series of talks co-curated by Alison Gingeras and the editors of Affidavit, Kaitlin Phillips and Hunter Braithwaite.