What Wasn't There

Emily LaBarge

January 14, 2019

,-1983.jpg)

Had I thought it would all become clear? The longer, the harder I looked? A life—born, lives, dies—and another—the same—and another—again. Flickers, flashes, splinters. What is left, and how to hold on to it? What to preserve and why, and for whom: to what beginnings and ends?

W. Eugene Smith, Louise Bourgeois, Barbara Loden, Lord Royston, Shinichi Suzuki, Marie Curie, Thomas De Quincey, John Keats, Marcel Schwob.

The writers of these lives, too, and how they render them—for they seem inextricably bound, all jumbled up. Sam Stephenson, Jean Frémon, Nathalie Léger, Lydia Davis, Fleur Jaeggy.

I have been keeping strange company.

Born, lives, dies.

Born.

Lives.

Dies.

And yet no life is the same as any other, though there may be shared characteristics, particularly in certain modes of telling. I read these slender volumes that transfix me—these spare and idiosyncratically written lives and works of artists, writers, scientists, musicians—and I wonder what to call them. Their brevity stuns, stings the eyes, raises the hair on the nape of my neck. Could a person loom at once so large and so small? Whole lives, immense feats and works pass in a matter of pages. Vast archival sources are whittled down to a sentence or two. Subjects escape their writers, refuse to be pinned to the page, disperse like a web or stutter like a grainy film. Writers refuse the one-dimensionality of their subject, speaking to everyone around them, instead: a collective portrait in negative space.

Condensed Biographies, I have been saying to myself, Compressed Lives, how about Briefly Noted, or This Is Not a Biography, which in my mind plays to the tune of “This Is Not a Love Song”, by Public Image Limited. One night I have a dream in which John Lydon gyrates in his grey suit, his orange hair and blue sunglasses spotlit, just like in the music video. Romanticism and Realism are dead, he tells me, I just want to fuck. Happiness and sunshine, this is not a biography, no no, no no. I ask him, What isn’t a biography? and What is it then? But he just looks at me and jeers, pityingly. In my somnambulant state I am not surprised, but I am disturbed: what does rotten Johnny know that I don’t? I’m sure I have no idea what any of this means, but I think it must be something about transubstantiation and maybe even magic—the shifting of one form, one substance into another. A life in words. A life made out of words. The structure, the syntax of a life.

What is it you would want to say, I keep asking people, if you had to sum it all up?

Such possibility. I think we know that we can’t have it all. Spare it, pare it, boil it down to the bare necessities, and in these, a kind of radical truth. Perhaps biographies are really about editing, an editorial process: fleshing out where there is none, stripping back where there is too much.

But you can never know what the most important parts of your life are, what it’s really made up of, until it’s over. And who’s left to say then?

I spoke to Sylvia. “Do you think this is a good life?” The table held apples, books, long-playing records. She looked up. “No.”1

A friend tells me, explaining why he now writes investigative journalism instead of poetry, that we understand ourselves by writing about others. That’s when you see who you really are, man.

Another quotes Virginia Woolf’s Orlando, “a biography is considered complete if it merely accounts for six or seven selves, whereas a person may well have as many thousand.”2

You’re not a biographer and no one is writing your biography, you’re not writing an autobiography, so what’s the real problem here? my mother asks me, to which I have no answer. No one knows my name, it’s true.

A maudlin, indescribable kind of despair sets in. Time seems to both slow and speed, inexorably. I’m not exaggerating for literary purposes. This really happened. This is like love, I keep saying to myself, unsure of what I mean, as I read of births and deaths, fleeting lives that spin into the distance, and tears plop onto my sad scraps of paper with their sad incoherent scribbles.

The births, the deaths, they stick in my throat.

Beginning and end simply are a life; they are the definition of a life, without which it would not exist. So why feel such auspiciousness and such aberrance at their mention, these unextraordinary events?

These people, these people are all gone, and I’m still here. I’m still here. I’m still here.

I am unhinged, I tell my partner, who nods and looks wary. Her life flashes before her eyes. It is not very interesting.

It’s foolish, yes? And melodramatic, to be sure, the way mortality (mortality!) rushes so rapaciously into what was simply to be an essay about a handful of contemporary publications that—through extreme narrative compression, structural experiment, and evocative inhabitation of source materials—resist traditional biographical conventions to produce something different. Books that seem to say biography is discursive and intertextual, many-voiced and self-consciously evincing, even evading, its own sources and processes. Biography as telegraphic, biography as telepathic. And always the author hiding herself somewhere within, because it’s true that we see ourselves in others, whether we want to admit it or not.

Go, go, go, said the bird: human kind

Cannot bear very much reality.

Time past and time future

What might have been and what has been

Point to one end, which is always present.3

I’m not usually like this.

Well anyway, this is what happened, and here are my notes.

1.

,-1470.jpg)

There are precedents, of course. Giorgio Vasari’s Lives of the Artists, the definitive edition of which was published in 1568—biographies of the famous Italian Renaissance artists, from Cimabue to Titian, which range in length from 6 to 75 pages. It’s all in there, they told us in my Renaissance Art History classes: if you need to know something about one of these painters, just look it up in Vasari. Good old Vasari! They told us lots of things, though, like not to use the word beautiful, even if something was. They didn’t tell us what I now see in Vasari’s Lives—his predilection for gossip and strange, colorful detail; the significant role of extended horoscopes in describing an artist’s origins; his use of artifice (artificer) rather than artigiano (artisan) or artista (artist), because the former comes from the Latin artifax, which can also mean God the Creator; that contemporary critics and translators despair at his overuse of the adjective “beautiful.”

Just over 100 years later, John Aubrey was beginning his Brief Lives, mostly one to two page chronicles of eminent British seventeenth-century men: writers, philosophers, astrologers, doctors, scientists, soldiers, sailors, lawyers, dignitaries of state and the Church of England. In these abridged lives, Aubrey wanted to preserve, rather explicitly, “the naked and plaine trueth, which is here exposed so bare that the very pudenda are not covered, and affords many passages that would raise a blush in a young virgin’s cheeke.”4 Aubrey described his work as “remains”—“tanquam Tabulata Naufragy [like fragments of a shipwreck]”—the retrieval of which “from Oblivion in some sort resembles the Art of a Conjuror, who makes those walke and appeare that have layen in their graves many hundreds of years.”

The Art of a Conjuror, see? The mini-biographer possesses a dark magick. His omniscient posthumous narrative is razor-sharp and raises these spectres from their graves—crimson pudenda ablush!—so their deeds may play out again and again. For the pleasure of the living, I suppose, for our edification.

So I know that Michelangelo was born “on the sixth day of March on Sunday, around eight o’clock at night” and that the horoscope of this birth “had Mercury ascendant and Venus entering the house of Jupiter in a favourable position, showing that one could expect to see his accomplishments miraculous and magnificent works created through his hand and his genius.”5 I know that Giotto painted a fly that looked so real, his teacher spent days trying to swat it away. I know that Thomas Hobbes had hair so black “his schoolfellows were wont to call him Crowe,” and that from an early age he was afflicted by “a contemplative Melancholinesse.”6 I know that there are no women in Vasari’s Lives, and only the briefest of the brief in Aubrey’s, in which they are born lovely, comely, meet a man, fall into “ill repute,” and die—save the very few wealthy and independent enough to spare themselves the ignominy.

But what else?

2.

A catalogue, a taxonomy, an encyclopedia, an index, a file, a log, a record, a list, a litany of facts. The details pile up and pile up. They run down the page, jog, sprint, tumble, collapse. More and more, in quick succession.

There are:

…reels of film, Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, all of you on vacation, on Sundays, at Luchon, at Le Cannet, Father’s pebble collection (in another shoebox), the dresses Mother had made at Poiret’s, account books, old papers, rags, dishcloths, handkerchiefs embroidered with everyone’s initials, lace camisoles, tablecloths, curtains, buttons, half-empty perfume bottles, scarves, shawls, furs, what remained of the tapestries, including the scraps half-devoured by moths, hats, pipes, canes…and the electric fan.7

A ragtag family history, a profusion of memories and souvenirs fills the four-story townhouse (five if you include the basement) at 347 West 20th Street in New York City, where Louise Bourgeois lived and worked from the 1940s until her death in 2010. Jean Frémon was a lifelong friend of Bourgeois, and the artist’s studio-home is well-documented in both photograph and oral history as overflowing with all manner of objects. In Now, Now, Louison, Frémon engineers what seems a haphazard stack, but in which each detail carefully speaks of Bourgeois’s personal history, her familial ties, what she brought with her from France to the United States, and what repeat as material and thematic preoccupations throughout her body of work. Most poignantly, the sense of a private lexicon that is made external in her vast oeuvre of sculptures, paintings, drawings, and installations.

A list can summon a person whole. Think of Roland Barthes’s “I like, I don’t like” in Roland Barthes by Roland Barthes, in which he lists, well, what he likes and what he doesn’t like. Salad, cinnamon, lavender, cherries, watches, Twombly, trains, the Marx brothers, etc. (like) and geraniums, telephoning, spontaneity, strawberries, women in trousers (!!) and so on (don’t like). “This is of no importance to anyone,” he writes, this apparently has no meaning. And yet all this means: my body is not the same as yours.”8 There is an intimate specificity to the terribly ordinary details of a list. They combine to produce a tableau, a still life—each object takes on extra weight and significance, particularly within a narrative structure. A list could go on and on, and presumably does. But here, what is frozen before us?

Nathalie Léger’s Suite for Barbara Loden begins with the author trying to write a short entry about her subject for a film encyclopedia. Even as she is eluded by a paucity of stable sources on the filmmaker, Léger struggles to contain her task, writing more and longer—the more she knows about Loden, the more she realizes is missing, the story deepens. She thinks of Georges Perec, who wrote, “To start with, all one can do is try to name things, one by one, flatly, enumerate them, count them in the most straightforward way possible, in the most precise way possible, trying not to leave anything out.”9 But maybe it doesn’t work that way when what you’re trying to describe is a person.

The longest list of all, the most comprehensive, compulsive, crazy, belongs to the photographer W. Eugene Smith, as chronicled by Sam Stephenson in the opening pages of his rich and innovative biographical study, Gene Smith’s Sink. Towards the end of his life, Smith gave his archive to the Center for Creative Photography at the University of Arizona. Twenty-two tons of material, it included thousands of prints, negatives, contact sheets; hundreds of personal notes and letters; maps, diagrams, magazine and newspaper articles; 25,000 vinyl records and 3,750 books; and 1,740 reels of tape containing what Stephenson would find to be 4,500 hours of audio recordings made by Smith in the New York loft in which he lived from 1957-1965.

Stephenson describes Smith’s loft, a fourth-floor walk-up on 6th Street where prominent jazz musicians of the period stopped after hours for late night jams and revelry, much of which was preserved by Smith’s idiosyncratic home-recording rig: “He had wires running like veins through walls and floors, connected to microphones on one end and a reel-to-reel tape machine in his darkroom on the other end. He recorded comings and goings all night.”10

Wires like veins, veins like wires. As if the building was alive; as if the building was Smith; as if Smith was the building. I picture the wires writhing and coiling in the air, fraying and flying like mad tentacles: a network of conduits coursing with live matter, thrumming, igniting whatever they touch.

3.

,-1957.jpg)

How much of me is someone else? How much of me is the people I know—peers and compatriots, foes and failed relationships? People I’ve never met, but whom I admire from afar. Everyone and everything I’ve ever read. The people who write or make work alongside me: our brief intersections; our disagreements and disappointments; our desire, our ardour, our reaching towards each other, and away, looking for more, for different, for other. My interior bulges with the bodies of others, I can almost see their faces straining against my skin. Stephenson’s account of Gene Smith is a story of Smith by what surrounded him. The photographer flickers through first-hand accounts from the vast array of people Stephenson tracks down and interviews in person, tenderly drawing from them details about Smith that include often intimate details of their own lives, too.

Each chapter acts as a kind of composite portrait in which Smith emerges in the negative space of the speaker’s narrative, and in Stephenson’s careful and attuned observations. There are people who worked with Smith, jazz musicians who frequented his loft, neighbours, collaborators, fellow artists, lovers. More than simply account for various pieces of information about Smith’s life, these individuals also seem to mirror or to echo him in various ways. Some share Smith’s lifelong intellectual or formal preoccupations, others, his addictions and behavioural tendencies—a desire to be independent and to exist on the fringes, to pursue, monomaniacally, one’s creative impulses, to look at the beauty as well as the darkness of life, to escape, to descend into the oblivion provided by alcohol, Benzedrine, speed, heroin. Some share all of these things, all mixed up, maybe we all do, a little. In Gene’s Smith Sink, through Stephenson’s sensitive writing and structuring, it is as if a biography could be a tendency or a pure form, rather than a series of facts. A biography could be the affinities of all the people it contains and their collective predilections—as if they share something deep and elemental, all versions, iterations of the same substance.

Coursing. Thrumming. Wires like veins.

Which is not to say that Smith isn’t presented as an individual, with a specific life and set of experiences. But that from Smith, and from those who lived around him, some of whom remain, Stephenson draws something even more idiosyncratic and spectacular — a person multiplied and refracted in singularity. Stephenson’s approach resonates with nuance through the book, appearing in different guises, hidden in particulars or source quotations, like this one about a live broadcast of Thelonius Monk and the jazz composer, pianist and teacher, Hall Overton, who had a studio on the same floor as Smith:

Monk demonstrated his technique of “bending” or “curving” single notes on the piano, the most rigidly tempered of instruments. He drawled single notes like a human voice and blended them to create his own dialect, like making “y’all” from “you all.” “That can’t be done on the piano,” Overton told the audience, “but you just heard it.”11

Smith’s photographic output and personal archive are prodigious, and Stephenson spent 24 years immersed in both.

“It’s much better if viewers of art are asked to work hard,” Mary Frank (former wife of the photographer Robert Frank) tells Stephenson when he visits her studio.

Gene Smith’s Sink is 204 pages long and contains no images.

4.

“How to dare to describe her, how to dare to describe a person one doesn’t know?”12 wonders Léger in Suite for Barbara Loden. It’s a good question. In Gene Smith’s Sink, Stephenson describes his desk, which is the origin of the book’s title: it is fashioned from Smith’s old darkroom sink, which now rests in a metal frame and has a desktop of security glass fastened to its basin. “If somebody wanted to use it as a darkroom sink again,” Stephenson writes, “the integrity of the original object is maintained.”13 Is this how to describe a person? To lovingly inhabit while also leaving them whole for whomever might come along next, for someone who might wish to describe or to interpret them in a different fashion?

As Léger pursues the scant details she can find about Barbara Loden and the 1970 film she wrote and starred in, Wanda, the writer wonders about her place as interpreter: what to do when there is a profusion of nothing, but one can feel, marrow-deep, that one knows a person intimately. The sense of her, the texture, the impulse, the affinity, the anxiety. “A ‘description’ is an “imperfect definition,” Léger reads in her dictionary, it is a “gathering of accidents by which something may be easily distinguished from some other thing.”14 The happy accident, the imperfect, the accidental is perhaps enough, is perhaps too much. “Make it up,” a famous documentary filmmaker calmly advises her, “all you have to do is make it up.”15 An interesting proposal that inflects the book with a sense of the personal, as if Léger’s voice is intertwined with the narrative she weaves in and around Loden and Wanda, and the film’s Wanda, played by Loden: more refractions, a woman inside a woman inside another woman—women through each other—how so many of see ourselves in any case.

Léger’s most powerful observation is that Loden’s film—which chronicles a failed bank robbery by a woman, Wanda, and her coercive happenstance partner, Mr. Dennis, in a small coal mining town in eastern Pennsylvania—is really about Loden. Not the bank robbery, naturally, but Wanda’s passivity and aloneness, her vulnerability and the sense that she is somehow sleepwalking through life, stumbling into and out of whatever arises on her path. As Loden herself said, “Wanda’s character is based on my own life and on my character, and also on the way I understand other people’s lives. Everything comes from my own experience. Everything I do is me.”16 And so the book is also about other women, like Loden, like Wanda, which is maybe all women, on any given day. Women who are prickly and sometimes absent; women who have experienced violence; women who find ways to escape. Léger writes of Marguerite Duras, Sylvia Plath, Chantal Akerman, and other women including her own mother—a host of matriarchs who coalesce to flesh out the incomplete portrait of Loden. The bringing together of these subjectivities is fine succour, a radically empathetic mode that, like Stephenson’s Gene Smith’s Sink, describes a person by briefly populating his or her fulsome absences.

I follow Léger’s lead and look up the definition of “suite,” which I know to be a set of rooms as well as a form of instrumental musical composition and arrangement. I find it also to be the personal staff of a ruler, a set of matched furniture, a group of things forming a unit, and a collection of minerals or rocks having some characteristic in common (such as type or origin),17 which I like very much. Family resemblance, you see? Different rock, different time, same vein, ore, glimmering detail, flint and fault line.

I think of James Abbott McNeill Whistler’s portraits of women, Symphony in White numbers 1 to 3, and how an image of a woman might also be a piece of music. Yes of course, a composition, one, two, three women in repose. I think of Louise Bourgeois, who made works on staved paper, her series of 25 drawings entitled Lullaby (2006), for instance, the cover of which has no notes, just the title printed in block letters in red across the middle of the 8th and 9th staves, signed ‘LB’ in red in the lower right corner, where a coda might normally be. And that’s how I think of Frémon’s Now, Now, Louison (whose cover is in fact designed after Lullaby). A coda, which is an expanded cadence at the end of a piece of music. A suite, a fugue, a variation on a theme, which is the life and work of Louise Bourgeois.

“I love you,” LB wrote in red cursive across a different set of blank staves; and across another, a hairy spider whose legs reach to the edges of the page, with half and quarter notes floating in between—E, G, G, A, C, E. On the verso, an inscription: “Do I have to dance upside down naked to get one of these?” Every Good Boy Deserves Fudge, they taught us in piano class, but what about Good Girls? What do they get? Frémon’s text is very much a web, woven in the original sense of the textual—textere, in Latin, to weave, to join, to fit together, braid, interweave, construct, fabricate, build. Bourgeois, the spider woman, and Frémon the spinner of yarns. Like Léger, Frémon seems to dissolve into his subject: pronouns shift endlessly with no stable centre and the voice and tone of the writing oscillates accordingly—I am writing to you are talking to her is calling to them are painting for us and there she goes again and again and again.

Your story is not the only one they’ve told you, the one they wanted to make you believe. We’re all stories, layers of stories, the interwoven stories of others, of parents, of elders. They see themselves in what they tell you, thanks to the enormously devastating good faith of those who pride themselves on having been there. We are what others say we are. Our name accumulates little by little from shards of being.18

I believe this. And so, Now, Now, Louison is a devotional weaving; a web of love, to be perfectly sentimental, because why not. We write things to contain them, to learn their language, to love them better, to allow them to accumulate, to build and break, and then to let them go.

5.

This one, I’ll keep as brief as possible.

Lydia Davis!

She’s up to her usual tricks.

A kind of translation. Or a puzzle. A game. To find the story inside the story. The text inside the text.

Japanese musician Shinichi Suzuki’s autobiography, Extracts from a Life; Lord Royston’s early 19th-century letters home; Françoise Giroud’s biography of Marie Curie, Une Femme Honorable; and the memoir of Davis’s own great-great-grandmother’s younger brother, Our Village.

From each of these Davis extracts and occasionally reorders passages. In some cases, she translates the extracts herself, always preserving the strangeness of the language—awkwardness and sentimentality are to be prized.

Because these are parodies, in a way. There are patterns to how people tell their lives and the lives of others. For obvious reasons—heritage, posterity, habit, among others.

Funny to see, again and again, the official accounts that contain a life.

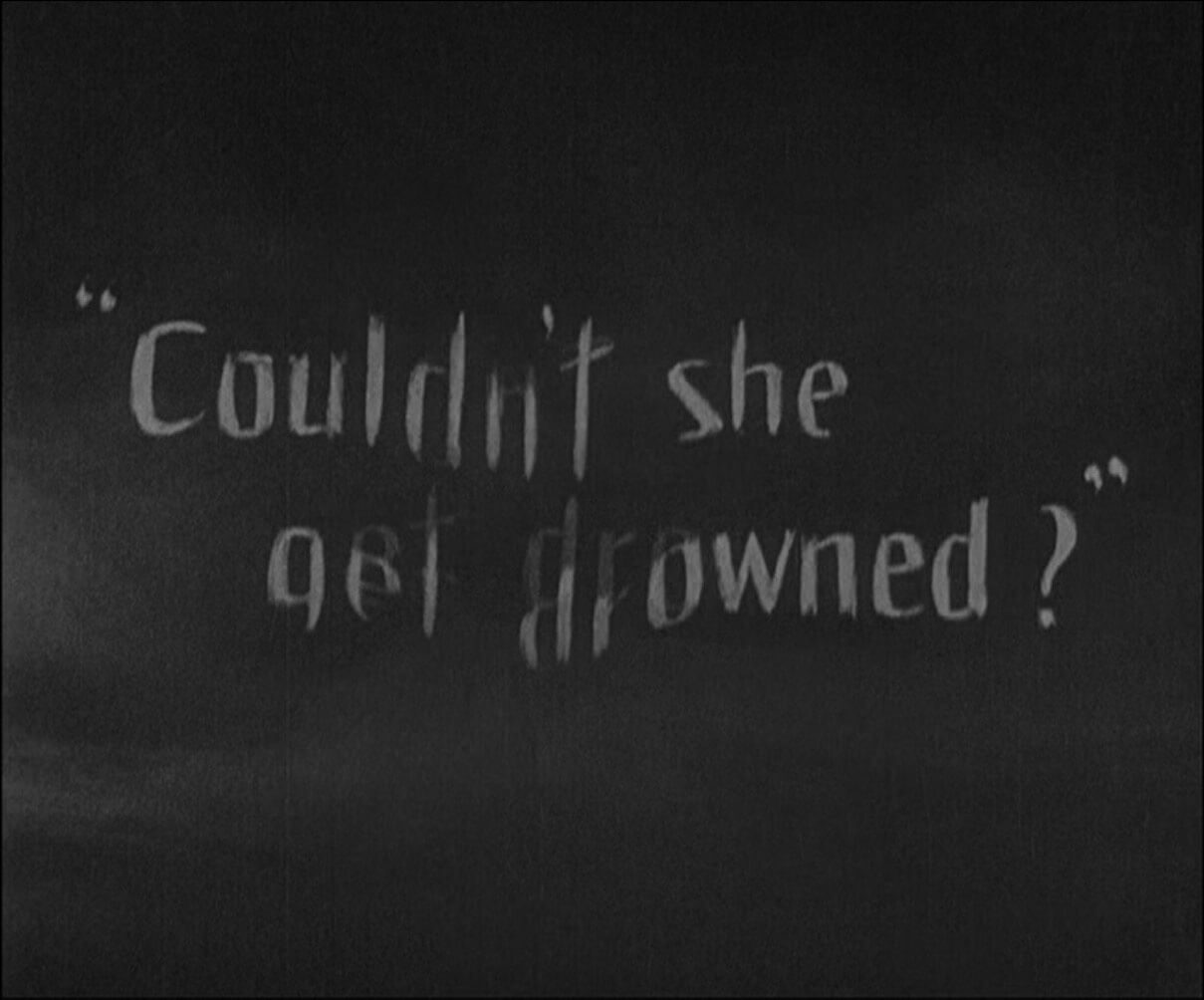

They have intertitles!

Like in a Dickens novel, David Copperfield, say: I AM BORN, I BEGIN MY OWN ACCOUNT AND DON’T LIKE IT, I AM INVOLVED IN MYSTERY, and so on.

But also like a silent film, with bursts of energy and movement, manic vignettes of action, and in between, black screens with flickering white script, simultaneously introducing and commenting on what is to come and how we should read it. Containing it, too: the moment begins and ends, decisively, has its particular time slot in the narrative, which is not something that eddies and elapses, like time actually does, but solidifies in sequence.

Some of them are grammatically nonsensical.

Marie Curie?

“Research. To extract uranium from pitchblende, there are at that time factories. To extract radium from it, there is a woman in a hangar.”19

“Children. Marie makes jams and the clothes of her daughters out of a spirit of thrift. Not from zeal.”20

Responding to her husband’s death?

“Marie. Marie remains frozen; then she says: ‘Pierre is dead? Completely dead?’ Yes, Pierre was completely dead.”21

Nearing the end of her long and impressive life?

“Time Passing. And now the red curls of Perrin, discoverer of Brownian motion, have become white.”22

“Conclusion. She was of those who work one single furrow.”23

The single furrow. I admire that.

Of Lord Royston’s letters, Davis has said, “this other text seemed to be there in potential—there was something a great deal more interesting in it than what I was reading, the same language with a different shape and intention.”24

And also, “I’m interested in a different kind of premise about what so-called ‘fiction writers’ can be doing—a formal change that moves right out of the fiction genre and enters other genres at the same time, so that a text can be partly autobiography, partly fiction, partly essay, and partly technical treatise…”25

People do not often write of them as such, but I see Davis and the Swiss-Italian writer Fleur Jaeggy as sisters in compressed, tricky arms.

They know their use of language in and out. Translators always do. I believe they can cut to the quick in ways that other writers cannot. Maybe when they look at texts, a hidden text, spare and reduced, glows on the page, burns into their minds.

Jaeggy haunts me, with her inscrutable mini-biographies of Thomas De Quincey, John Keats, and Marcel Schwob: These Possible Lives. Each is based on extensive primary and secondary sources—diaries, letters, stories, poems, essays, biographies.

Thousands of pages condensed into a few sentences.

And Jaeggy chooses, each time, the most beautiful, arresting details and distils them into her own lucid, somehow terribly appropriate language: as if she harnesses and limns the bare prose bones of these dead writers.

I get stuck on the death scenes, in particular.

De Quincey, who said “Thank You” to whoever was around him. “They said that he had been a ‘good sick man,’ and a gracious corpse; he hadn’t wanted to trouble anyone.”26

Keats, “It will be easy,” he says to his friend Severn, trying to console. “Dusk entered the room. From when Keats said that he was about to die, seven hours passed. His breath stopped. Death animated him in the last moment.”27

Schwob, who shuts himself into his house in Paris and descends, appears to mutate into his own work—La Porte des Rêves, Le Roi au Masque d’Or, Vies Imaginaires: “He would never again want to leave. He felt like a ‘dog cut open alive.’ Won’t the dead come to talk for just half an hour with this sick man? His face coloured slightly, turning into a mask of gold. His eyes stayed open imperiously. No one could close his eyelids. The room smoked of grief.”28

That’s!

All!

Folks!

I did not love it, I loved its burning down and, you know, I haven’t loved anything since.29

This was when my heart sank and became difficult to revive.

6.

In On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection, poet and literary critic Susan Stewart writes that “minute description reduces the object to its signifying properties, and this reduction of physical dimensions results in a multiplication of ideological properties.”30

The idea that the biggest thing could be the smallest thing, could be located in the smallest thing—it dazzles and consoles.

But what are the signifying and ideological properties of the moments of a life? The descriptions big and small? I realize I’m trying to apply a kind of morality to a form in a way that is probably not possible.

Why?

I want all of the tiny infinities.

I want to be the incongruous person, which is every person.

Nathalie Léger writes of how, while doing research for her Loden encyclopedia entry, she went to speak to Mickey Mantle (yes the baseball player!!) about his attempts to write an autobiography. He couldn’t do it, he told her. He had this vision of what it would be, but that was never what ended up on the page. He wanted it to be like when you were at the plate and the baseball was coming right at you, and you could see this hole in the air that was the trajectory of the ball.

It is not that I am afraid of death, but that if there aren’t the right words—dead or alive—it will be like I never existed at all.

Yes, she was completely dead.

I didn’t find myself in any of these subjects or their writers. Not out of lack of sympathy, but maybe because I often feel like I’m expected to be someone else. I suppose this could be read as an unwillingness on my part to be who I am. And so I am reticent. And so I admire these writers, their subjects and subjectivities, even more.

And what is a subject.

And what is a self.

No, I didn’t find myself here, but I did dig a hole to fall into. Isn’t that what a life is anyway, and writing, too.

There is a moment towards the end of Gene Smith’s Sink that stays with me. Stephenson writes, “the photographer David Vestal, Smith’s friend and advocate, once told me that Smith’s problem was that what he saw wasn’t there, so the camera had no way of recording it. That’s why he had to work so hard in the darkroom.”31

What he saw wasn’t there. What was not, what is not there. Yet. I love that. We don’t need to know, but oh, how we do.

-

Donald Barthelme, “The Indian Uprising”, in Sixty Stories (London: Penguin, 2003) p.102.

-

Virginia Woolf, Orlando: A Biography (Ware, Hertfordshire: Wordsworth Editions, 1995) p.153.

-

T.S. Eliot, Four Quartets (New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2014) p.59.

-

John Aubrey, letter to Anthony Wood, MS Aubrey 6, fol. 12, Two Antiquaries, in John Aubrey, Brief Lives, ed. Oliver Lawson Dick (London: Vintage, 2016) p. xviii.

-

Giorgio Vasari, ‘The Life of Michelangelo Buonarroti, Florentine Painter, Sculptor, and Architect’, in The Lives of the Artists, trans. Julia Conway Bondanella and Peter Bondanella (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991) p.415.

-

Aubrey, p.149.

-

Jean Frémon, Now, Now, Louison, trans. Cole Swenson (London: Les Fugitives, 2018) p.2-3.

-

Roland Barthes, Roland Barthes by Roland Barthes, trans. Richard Howard (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994) p.116-117.

-

Nathalie Léger, Suite for Barbara Loden, trans. Natasha Lehrer and Cécile Menon (London: Les Fugitives, 2015) p.10.

-

Sam Stephenson, Gene Smith’s Sink (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2017) p.60.

-

Ibid, p.146.

-

Léger, p.10.

-

Stephenson, p.7.

-

Léger, p.18.

-

Ibid, p.26.

-

Ibid, p.27.

-

Definition of ‘suite’, Merriam Webster online, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/suite [accessed 8 December 2018]

-

Frémon, p.70.

-

Lydia Davis, “Marie Curie, So Honorable Woman”, in The Collected Stories of Lydia Davis (London: Penguin, 2009) p.410.

-

Ibid, p.411.

-

Ibid, p.414.

-

Ibid, p.421.

-

Ibid, p.422.

-

Lydia Davis in Larry McCaffery, “Deliberately, Terribly Neutral: An Interview with Lydia Davis”, in Some Other Frequency: Interviews with Innovative American Writers (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1996) p.74.

-

Ibid, p.76.

-

Fleur Jaeggy, These Possible Lives, trans. Minna Zallman Proctor (New York: New Directions, 2017) p.24.

-

Jaeggy, p.48.

-

Jaeggy, p.60.

-

Paul Celan, ‘Conversations in the Mountains’, in Paul Celan, selections, ed. By Pierre Joris (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005) p.152.

-

Susan Stewart, On Longing (Durham: Duke University Press, 1993) p.48.

-

Stephenson, p.183.