Accumulation and Appreciation

Sophie Haigney

December 15, 2020

We start collecting with rocks. We begin, then, in the realm of prehistory, poring over minerals that might be millions or billions of years old, numbers so large and abstract that children might spend hours trying to conceptualize them. Rocks are easy targets for young collectors, in part because there is an abundance of rocks almost everywhere on earth. But the point is that there are certain rocks that we choose, taking them into our hands and pockets and jars; rocks that become our rocks.

I remember the feeling, as a child on a beach in New England, of finding a flat black rock with a thin stripe of quartz running through it like a vein of white blood, and putting it in my pocket. I also remember a certain disappointment that would set in later, when the rock came to look like a rock again. This is a problem, it turns out, for many collectors, and also part of the drive: the hope that there’s a rock that won’t just turn out to be a rock.

From rocks we move on to buttons, to snow globes, to stamps, to quarters from every state. It is an act that requires some amount of patience, one that most of us at some point abandon. As we get older, we may find ourselves trying to shed our things rather than accumulate them. But some people keep going. Some people, if they have the means, go in for art.

*

The vast majority of the world’s art is in private hands. It’s hard to estimate how much, because of course there is no definition of art, and even if there were, no way to track down and quantify what exists behind closed doors. (I like that phrase, “behind closed doors,” which conjures for me a series of ornate portals lined up and shut, hiding treasures). It is safe to say that when we think about all our neat categories of cultural heritage—Great Masters, Contemporary Art, Antiquities, et cetera—more of it exists in private than in the public domain. Some of it is hanging on walls; quite a bit is sitting in massive storage spaces, with air that’s been filtered six times, appreciating.

This reality has been the cause of handwringing and a general feeling of malaise in the art world for decades now. It has become a cliché to bemoan the state of “the art world,” the fact of private collections and collectors, to complain about the circus of fairs and biennales, the ever-rising prices, Jeff Koons. There is always talk of a bubble. There are endless headlines about auction prices: The Most Expensive Painting Ever? Records Broken! There are more and more glowing stories in glossy magazines about young collectors supporting young artists. Despite the absence of an in-person fair this year, amidst a pandemic, some stragglers have still traveled to Miami Beach for whatever remains of the circus of sales and deals. It’s all very tedious and insane.

Some things about this are new and some aren’t. The Romans, for instance, collected the Greeks. The English, on Grand Tours after their time at Oxford, ended up in Rome and brought back statues, busts, altars, columns, rocks. Americans, later, made a voracious art of buying up Old Masters with their newly mighty dollars. Now, in the “globalized” art market, money flows from new directions, encompassing a constant exchange of capital and objects across borders and continents.

You might think these realities would make the whole process more seamless and in some ways perhaps it is; people can even buy shares in art now, maximizing profit with no contact with the object, the entire thing free of friction. But there is still, as much as ever, a fetishization both of the object and of the person who collects. There is still the same old story of the collector’s passion, or drive, or addiction. On a list of 50 Most Discerning Young Collectors published in 2013, one of the fifty said, “Collecting is similar to falling in love. You think, I can’t live without this and what the hell do I do with this?” Another said, “Visiting museums is a lot like practicing your golf swing on the driving range: If you want to be good, you have to practice.” These same tropes—collecting as a romance, collecting as a high-level competition, collecting as an addiction—are recycled over and over.

*

Once I interviewed a private collector for a short article about his photography collection. It was a breezy conversation, something that would run under a headline like “Five Questions for Great Collectors.” His apartment overlooking Central Park had a really nice carpet, the kind that makes you want to curl up like a puppy. He told me the kind of story they always tell, about the first photograph he bought for $200 in his late 20s, and how that became the basis of everything else. There were so many photographs that it was hard to see the wall. Some were arresting: early prints of Marilyn Monroe, Mapplethorpe peonies unfurling, a very small image of a burning American flag. He kept saying the word “originals,” something that meant very little to me emotionally but clearly meant quite a lot to him. “I only buy originals,” he said.

I wondered as I sat there how much an article like this would increase the value of his collection. I didn’t end up writing it, but not for lack of trying: the framed photos didn’t show well in photographs for the magazine. I got paid $50 for my time. Later I thought, well, that’s probably what that hour was worth, spent as it was in an apartment with a beautiful view overflowing with photographs.

The sheer mass of photographs in that apartment, the way they crowded into each other on the walls, made me think of the word “hoarder.” As a society we are interested in the concept of hoarders, though we take it to mean something different than collectors. Hoarders are vulgar, perhaps even disgusting, though we do like to look at them, based on the number of television shows and documentaries premised on peering into basements stuffed with junk. Hoarders are not seen as collectors, which is partially an economic distinction: the market sees their bounty as junk, while collectors’ has “value.” But it’s partly also about a certain economy of objects, the notion of connoisseurship and selectivity, that idea of “originals” that was repeated to me during that interview, the idea propagated of a collector’s particularly discerning “taste.” Still, hoarders and collectors have a lot in common: the steady accumulation of things for no particularly good reason, to the point that they might begin to crowd you out, to overflow into crevices of your apartment and then into storage spaces made necessary by acquisition.

And in the truest sense, the man I was interviewing was more of a hoarder than a man who saves years’ worth of old newspapers in his basement. All art collectors are, keeping to themselves something that is at once truly unique, “original,” and an exchangeable commodity that grows more valuable with time. All wealthy people are hoarders, stockpiling assets for themselves against an imagined coming storm. The principle remains vaguely absurd to me, despite being one of the dominant truths of the market, which is itself absurd to me: anything you can hold onto tightly enough, and keep to yourself, whether property or stocks or paintings, tends to become more valuable with time. This is a logic called “appreciation,” a funny word because it is used more often to describe the pleasure we feel when we look at a piece of art.

*

“Neave wanted what he appreciated—wanted it with his touch and sight as well as his imagination,” Edith Wharton wrote, in my favorite story about a collector, called “The Daunt Diana.” It’s about Neave, a collector who becomes obsessed with one statue of Diana in an old gentleman’s art collection. When Neave comes into a windfall fortune, he buys the whole lot of it. But something about having the collection leads him to fall into a spell of apathy; he puts everything for sale at a massive loss. Then Neave begins, slowly, to buy the things back, at staggering prices. He’s miserable that he can’t get his hands on the Diana once again.

At the end of the story, after some years, the narrator returns to find Neave surrounded by his things, “not displayed in tall cabinets and on marble tables but huddled on shelves, perched on chairs, crammed in corners, putting the gleam of bronze, the opalescence of old glass, the pale lustre of marble, into all the angles of his low dim rooms.” Neave, once a powerful collector situated in an airy palazzo, now might be properly called a hoarder, and yet his hoarding is characterized by a certain dignity. Above his bed is the Daunt Diana, humbly shown, but more beautiful and strange than ever.

I like this story, probably, because it’s a little bit didactic—it’s partly an old-fashioned morality tale about what money can and can’t buy, the relentless dissatisfaction that accumulation can breed, and the elusiveness of our communion with art objects. Yet there remains something compellingly ambivalent in how Wharton writes Neave’s idolatry of the Diana; it’s at once borderline sexual and placidly pure. It can only ever be partly fulfilled, and must be fulfilled, anyway, in terms of conquest. He is willing to ruin his life for her, or rather for the stone statue for her, over and over. It’s hard to tell whether we ought to admire this impulse or not.

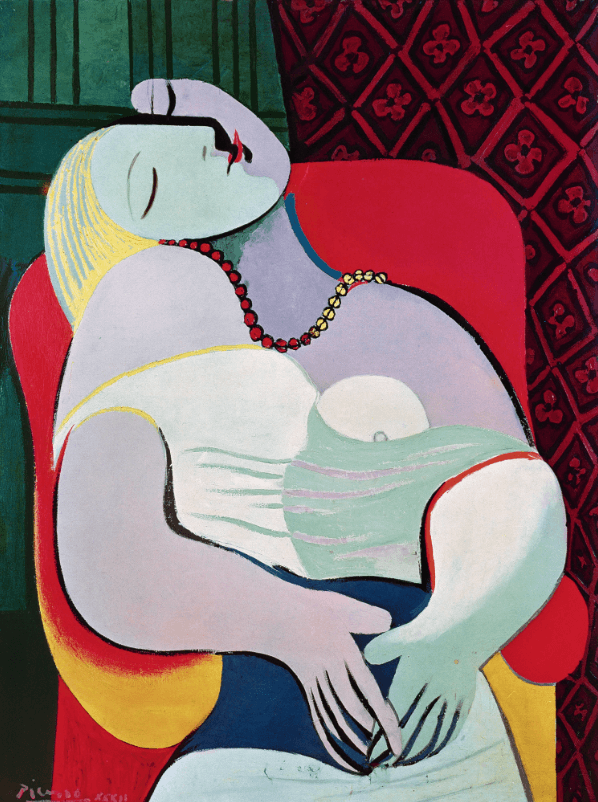

There’s another story I like about collectors, this one true, or at least it appeared in The New Yorker in 2006. In 2001, the casino magnate Steve Wynn bought a Picasso painting called “La Rêve” from an anonymous private collector—someone who had it “behind closed doors.” His friend, Steve Cohen, had agreed to buy it; once it was all worked out, for the largest sum ever paid at the time for a work of art, Wynn had some friends in town and decided to show it to them. He was gesturing, and suddenly his elbow went through it. “There was a distinct ripping sound,” The New Yorker reported. “Wynn turned around and saw, on Marie-Thérèse Walter’s left forearm, in the lower-right quadrant of the painting, “a slight puncture, a two-inch tear. We all just stopped. I said, ‘I can’t believe I just did that. Oh, shit. Oh, man.’” Then he turned around and put his pinkie through the hole in the painting, and he and his friends ordered a lot of wine and considered what happened.

This actually happened, but of course is also a sort of morality tale. Wynn is cast as a kind of anti-Neave: someone who has so much money that he doesn’t value his objects at all, someone so involved in displaying a painting to friends that he destroyed it, someone with no appreciation, no real reverence, for art. The gods got the better of him here and humbled him. But like Neave he is also, in this story, living amongst his things rather than putting them in mausoleum. The defacement of the sacred—the hole in the canvas—holds some magic for me, and I am strangely delighted by the image of a billionaire philistine’s pinkie extended through a Picasso. I’ll admit it. Also, the value was suddenly reduced, the planned transaction suddenly null. (Denis Johnson wrote a darker version of this story in “The Largesse of the Sea Maiden,” when a rich character thrusts a Marsden Hartley canvas into the fireplace just because).

Wynn’s wife, apparently, took it as a kind of fate, the broken object suddenly more valuable than all the other intact paintings they owned: “Please don’t sell the picture,” she apparently told him, or so he told The New Yorker, and so they didn’t. Until a few years later, when after all they decided to part with it and sold it to Cohen for $155 million. It was restored perfectly, though the damage was factored into the price. The story of the sign from on high that they ought to keep the painting became yet another myth, one that didn’t quite stand up to the market.

*

Let us return to the beach, to the child in New England carefully collecting her rocks. Unknowingly, she is participating in an endeavor that is about both aesthetic appreciation and something more scientific. She is conjuring some kind of order out of the world’s random rocks by sifting through and accumulating them. This, I think, is the collecting impulse in its most primal form, one not unlike that of a male bowerbird, who painstakingly gathers bits and pieces of plastic and glass and junk in rich shades of color. Some pattern is composed by the child on the beach, in her rock collection, even if it’s hard to discern. Part of what changes over time, if that child moves on from rocks to snow globes to fine art, is, of course, money. Or, maybe appreciation.

Collection of Influences: Susan Stewart, On Longing; Rhonda Lieberman, “Hoard d’Oeuvres” in The Baffler; Erin Thompson, Possession: The Curious History of Private Collectors from Antiquity to Present; Henry James, The Golden Bowl; Nick Paumgarten, “The $40 Million Elbow” in The New Yorker; Edith Wharton, The Custom of the Country; Ian Maleney, “Notes on Collecting,” Temple Bar Gallery + Studios Writing Commission.