Athens

Ben Eastham

April 23, 2018

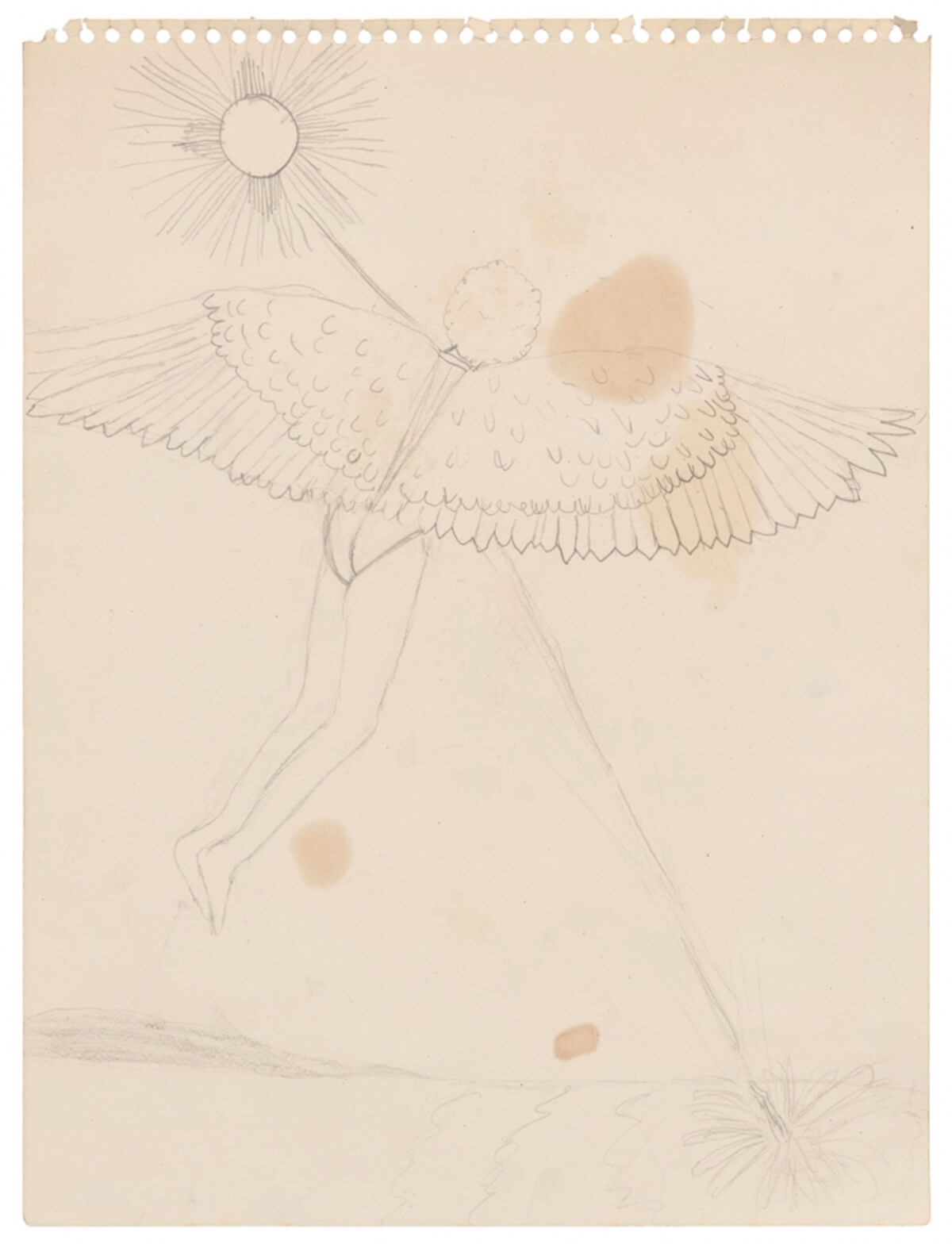

There is a pencil drawing by Robert Gober of Icarus as a beautiful winged boy. He is suspended in the sky like a minor angel at the center of the composition, his back to us. In the bottom right corner—the same part of the composition that claimed Breugel’s doomed hero—is the splash of two legs into the sea, and this is Icarus too. Gober, who was thirteen years old when he drew this scene on the page ripped out of a spiral-ribbed notebook, understood that Icarus is both at the same time.

It’s frustrating that, in narrative nonfiction, the attempt to combine several things in time results in noise. Even if the reader can follow the garble, they’re unlikely to be moved by it. But in a painting or a piece of music everything happens at once and is harmonious.

*

It was January, and I was in Athens to write a book about art. I was at a taverna because I was, on that day, failing to write a book about art. I joined three people I had seen the night before—a journalist friend from London who had moved to the city three years ago, and her two friends—as they waved from a table in the corner. They would not ask me how the book was coming along, or how well I was adjusting to being alone, or what I planned to do when my stay came to its end. For the first few weeks a city can be, if not exactly what you want, then at least what you need.

Xander leaned back on his chair, reached his arm around my back and with his left hand squeezed the tendons over my shoulder blade.

“You are ready?”

I said I hadn’t thought of readying myself.

*

I wanted to write a book about the times in which we live by writing about the art they have produced. I saw, or thought I saw, parallels between the markets around a certain strain of spectacular art and the speculative bubbles, untethered to reality, that underwrote the financial crises of 2008; between the obscurantism that surrounds contemporary art and a disdain for the general public that has undermined western politics; in the widespread reappraisal of neglected non-Western and non-male artists a forerunner or companion to the wider feminist and antiracist movements of recent years, and so on.

The book was a hubristic idea motivated, in truth, by a desire to prove to myself and to others that contemporary art—and by extension my career as an art critic—served purposes beyond boondoggling and money laundering. For the record, the preliminary selection included: a video following a masked monkey through an abandoned restaurant in Fukushima; a tent in which to watch a video cobbled together from YouTube clips of speeches, concerts and sports events; and the journey of a Kurdish artist who retraces his flight as a refugee from Turkey to Rome by walking hundreds of miles with a pole covered in mirrors balanced on his nose. The absurdity of the enterprise was part of its appeal.

I continue to believe that these artefacts from the recent past can help us better understand the storm driving us into the future. But with my knees hugging the space heater in a cold Exarcheia flat, surrounded by the books of the more talented writer from whom I was subletting it, I found myself writing something else entirely. As days passed without my speaking to a soul, with the exception of the gentle brothers who ran the small shop beneath the flat, I became less and less interested in writing critical appraisals of the best paintings, videos, installations, performances, immersive environments or choreographed scenarios that I had seen over the past decade. Instead I became preoccupied by loss, and specifically the suicide two years earlier of a young woman with whom I had been in love.

And so a description of a photography show transformed unexpectedly into the memory of seeing it with her; instead of a chapter explaining how a film had captured a generation’s disenchantment, I wrote the brush of her arm against mine as she leaned over to whisper in my ear while we watched it. I was unable to separate the work of art from the emotional circumstances of my experience of it, and even my present recollections of those past encounters were colored by the film of fresh regrets from a recent breakup. And so this book about art was shaped, quite against my will, by the death of someone I had loved and by another loneliness that I had more recently brought upon myself.

*

The musicians in the taverna were tuning their instruments. The waitress chatted away to Jane and Emma, and I gathered from her laughter and air guitar that they were telling her that this was my first experience of rebetiko. She smiled and, in English, welcomed me to the city. We ordered raki and then Xander said it was important that I understood. That things pertaining to Greek culture were important to understand was something of a refrain of Xander, who had the previous evening explained to me the importance of unflavoured raki and clay pot cooking. This charming, bearish man seemed to know everyone in the place, including the musicians who now sent him a wave.

“When modern Greece was born,” he began in the high rhetorical style of which he was fond, “tens of thousands of refugees came to Athens and Piraeus from the east. They brought music with them and combined it with the folk styles played by the workers in the kafeneia. Rebetiko is music for the poor, for the mangas who work on the ports and in the factories, it is music for the…”

He turned away and asked Emma, his German wife, for an English word, like an actor calling for a line.

“Yes, the underworld. The men who fight and play cards. The whores. The hashish smugglers from Turkey. All of the stories told by the songs are about these people and they are still about these people, about friends and neighbors. Because the old songs persist and new ones are written alongside them, and it is in these songs that people can be honest when they can nowhere else be. These stories were for them and now they are for us.”

We ate and we drank. Xander and Jane argued about how to interpret a song about a fifteen-year-old girl. The music quickened and people started intermittently to clap along. Drunk now, I tried to explain to Jane how it seemed to me that the bouzouki and fiddle melodies were responding to each other. “Yes,” Xander overhearing and leaning across the table to shout, “they are coming together, like lovers.” At which Jane rolled her eyes right up to the ceiling.

*

Speaking in a London bookshop two months later, the American artist said she’d like to try something out on her audience, find out whether they could overcome their famous British reserve. After her husband the musician had died, she said, she had come to find it therapeutic to scream for one minute each day. She looked out into the bookshop and asked, with a smile, “Will you scream with me?” Then she closed her eyes and screamed and the woman next to me thrust her head away from her body and screamed. And the sharply dressed young man to my right screamed, and his girlfriend screamed, and the many old people screamed, most of all.

Art delivers the world in small and ultimately harmless doses, a series of inoculations against the kinds of emotional trauma that might drive you mad. But after the woman I now find myself writing about died, I had not wanted paintings or songs or poems. Grief was a migraine, during which any crack of light or burst of music interrupts the attempt to distribute the pain evenly across one’s nervous system that is the only means of alleviating it. I needed to be left alone.

*

Two men stood up and made their way to the centre of the room; the players plucked pre-rolled cigarettes from aluminium cases and fixed them with spit to their bottom lips. The younger of the two dancers stood in the center of the cleared space while his companion kneeled on the floor at the edge of the circle. The musicians struck up a slow polka. On the first note the young man pulled himself up onto his toes and swept first one hand and then the other across his torso, bending his knees so that his body bobbed up and down as he drew shapes in the air with pointed fingers. The older man—an uncle, a family friend, a brother-in-law—clapped slowly in encouragement, never allowing his eyes to leave his partner’s. The dancer stepped crablike from one side to another and then twirled daintily on the spot, a move which earned the appreciation of the audience for what I guessed was its precision or simply its self-control.

The dancers swapped positions and the older man, his arms heavily tattooed and his tight blue shirt tucked in over a slight paunch into the waist of his jeans, took the floor. He swayed over his hips, reached up to the ceiling and down to his shoes, less delicate and more dramatic, more troubled. There was a tragedy in the manner that he curled up his hands to his face and, as the music slowed, in the glance he cast towards his wife at the table as he threw out an open hand to her.

*

Jane was telling me about being forced to talk in Greek to her landlady’s cat when there was a scraping of chairs to our left. The head of the table—a big-bellied, bald man with a moustache that reminded me of the picture of my grandfather that had hung over the dinner table in Preston—was getting to his feet. He was accompanied to the floor by everyone from the table excepting his wife, who remained seated while they kneeled in a circle around him.

As the band played a wandering kind of melody, he started to sway his broad body over his slender legs, pointing his hands down over small feet that stuttered to accommodate these redistributions of weight. As he moved in front of me and the room clapped, I thought about how his body must have changed over the decades that he had been stepping out this song. How his experience was caught in the different dips of his shoulders. He bent forwards, as if in mourning, and then threw his head up and the song stopped. With a nod to the crowd and a gesture to the circle that they should stand up, he turned and went back to his seat.

More raki came to the table and the conversation turned to the state of the city, to rent rises and income inequality, the generational gap between boomers and millennials, north and south. Xander’s unfiltered cigarette hovered above the table and when he lightly banged the bottom of his fist for emphasis its tip left a sharp trail of light like a sparkler.

“In Athens it is still possible to live as a man. You see this,” his hand sweeping around to encompass the scene, “is not possible in London or Paris or New York. There a man must give his life to money. I say again, only in Athens is it possible to be a man.” I shrugged. Jane pushed her chair back from the table, pointed a finger at him, and kicked off about who the fuck would want to be a man anyhow.

I wasn’t allowed to contribute to the bill. Xander pointed out that my guilt at not being able to pay was only another symptom of the psychology which reduces all human relations to one dictated by money, and that anyway if as a visitor from London I were to pay I would be reinforcing a power differential that socialism must seek to overcome. Turning to me, Jane shrugged and said it’s just the way it is here.

*

On the street, drunk now, I told her that memory is like the canopy of stars above us, the traces of historic explosions collapsed onto a flat plane, perceptible all at once. That the present is nothing more the position we occupy in relation to those events, charted by the patterns we make in the constellations of people and things we remember. A star is always alive where it is burning, and so the dead step across into the lives of the living.