Checkmate, Atheists: Intention and Ambiguity in Contemporary Art

Travis Diehl

October 23, 2017

“I sincerely hope OP is trolling, if not, this is all terribly depressing.” – Anonymous

On the internet, nobody knows if you believe in god. So users on the website ChristianForums.com come waving their flags. In 2005 a certain creationist thread evolved into a heated back and forth between Nathan Poe (who lists his politics as US-Democrat and faith as Agnostic) and user Carico (who only identifies as Christian). Their exchange led Poe to formulate the law that bears his name: “Without a winking smiley or other blatant display of humor, it is utterly impossible to parody a Creationist in such a way that someone won't mistake for the genuine article.”

A sincere post asks, if man evolved from monkeys, why are there still monkeys? In a clear satire, a dog sitting at a table with a jar of Jif wonders if dogs came from wolves, why are there still wolves? And yet, one can always be mistaken for the other. Poe’s Law suggests using emojis as a crude substitute for body language and inflection to signal the tone of posts. Against the austerity of plain text, or even pictorial memes, a smiley lets us know the poster is “just kidding.” It helps keep ambiguity in check.

It is not a perfect system. Even a clear statement of intent can be distrusted. Indeed, some views are so extreme that extremists don’t believe others might actually hold them. This is called Poe’s Paradox. A sufficiently extremist group will reject most applicants for not being extreme enough; they will suspect others of being parodists or infiltrators. The more extreme a statement—the more fundamentalist, controversial, or radical—the more it resembles its own satire.

Anonymity and pseudonymity are fundamental elements of online culture. Wherever one encounters a text without its author, Poe’s Law holds. When a meme is reposted, its context can easily change its reception—and its meaning. In a way, the author’s intent doesn’t matter; sincere or sarcastic, the result is the same. Ultimately, the work itself can make no definitive statement. Others will speak for it, and whatever original intent will be engulfed by the discourse the work provokes.

Consider another protocol: that of contemporary art. The four characteristics of online culture (what David Auerbach terms A-culture, for anonymous—but also asshole, accelerated, arch, etc.) carry over to the art world, too. Or at least to its web- and tech-inflected edges. Briefly:

Velocity: See artist Brad Troemel, author of “Athletic Aesthetics,” for whom the virtue of art production is defined as constant and repetitive movement—quantity over quality.

Irony: Rare is the artwork that does not come with the plausible deniability of an ironic read. The purely sincere artwork is pinned down, digested, inert; the one that hedges stays vital.

Self-Documentation: Time was, artists fretted over adjusting to the distribution conditions of Contemporary Art Daily. Now they plan how their shows will look on Instagram.

Elitism: Viewers of past avant-gardes may have had the feeling that art was a joke at their expense; today, viewers may feel like they’re being trolled.

And art, too, is subject to Poe’s Law. Where an artist’s intentions are unknown—where an artwork isn’t flagged as satire, or even as critical in any way—it remains possible, indeed probable, that some viewers will interpret (or misinterpret) the work as sincere. What Ben Davis calls “deliberately provocative moral ambiguity” settles in, deliberately or not.

As the viewer completes the work, they introduce a thrilling degree of chaos. In these extreme times, in need of extreme measures, even art that claims to solve, or simply confront, a social issue will have difficulty signaling, beyond all doubt, the difference between a “modest proposal” and a serious one. We expect sincerity; we expect irony. The problem arises when we can’t tell the difference.

*

In 2016, millennial ironists DIS curated the 9th Berlin Biennale, The Present in Drag. It became the signal exhibition of this new ambiguity. Among its many startup-like projects—a sustainable juice bar, a bitcoin trade fair—was Christopher Kulendran Thomas’s “New Eelam” (2016), an app-based housing subscription meant to replace traditional citizenship with “liquid,” transnational membership—what the press release describes as “the luxury of communalism rather than private property.”

For a monthly fee—like rent, but not rent—members will be able to stay at any one of the brand’s commonly (i.e., corporately) held properties in cities around the world. When British PM Theresa May called globalists “citizens of nowhere,” she meant it to be an insult; for Thomas, it’s a core virtue. In a promotional video, the New Eelam apartments are styled like gentrified heaven—a blonde-plywood and green-juice vision of an autonomous anyplace, invested not in localized communities (overcrowded, rotting, problematic) but in the cloud.

New Eelam pushes its concept just far enough to read as a satire of Airbnb, if not the millennial precariat in general. Then it goes further: New Eelam takes its name from Tamil Eelam, the autonomous socialist utopia imagined by the Tamil ethnic minority in Sri Lanka. In 2009, after more than two decades of war, their militant revolution was finally crushed with the help of Western arms; Western investors then moved in to secure the peace. Is it meant to be ironic when the voiceover describes this capitalist triumph as a “soft ethnic cleansing,” then embraces this model? The domicile-style settings that promote New Eelam at art biennials are decorated with work by Sri Lankan artists, which Thomas purchases in a booming young art scene.

Thomas’s work itself doesn’t signal that it’s a satire—it doesn’t smile—but it doesn’t insist on its sincerity, either. How do we know what the artist intends? Most contemporary art comes prepped by paratext: wall labels, catalogs, press releases, and checklists. With the New Eelam project, nested within a masterfully stage-managed exhibition, these texts offer no admission that the startup was anything but sincere. Where the work is silent, perhaps the artist themselves could provide a clue.

How do we “know” an artist? Through published interviews, their own writing, talks and panel appearances, social facetime in the art scene, historical accounts, rumors and secondary sources. But here, too, there is every indication that Thomas means for his startup to succeed. A mutual acquaintance says that he is in earnest; an article Thomas wrote for DIS Magazine argues for an embrace of capitalism similar to what New Eelam proposes. Another essay in DIS, written by Jeppe Ugelvig, states that “there is nothing fictional about New Eelam,” and notes that Thomas’s parents are Sri Lankan Tamil.

Yet suspicion lingers. (Not least because Poe’s Law encourages a degree of paranoia; better a cynic than a noob.) The fact remains that the gallery or the museum where we encounter an artwork is often sequestered from the artist’s intentions in a way that resembles the slipstream of the web. The environment of the 9th Berlin Biennale, styled by DIS to echo fashion, advertising, and net culture, only increased the sense of post-critical ambiguity and moral confusion. Whether the artist, like Amalia Ulman, seems to center their work on their real-world identity, or, like Puppies Puppies, extends an internet ethos to their trade name, they post under a handle, anonymous and unknown, their motives unclear.

But this ambiguity also maintains art as a space to tackle difficult subject matter and air extreme opinions. Thus the Biennale’s own ad campaign echoed the giddy trolling of the alt-right with such slogans as, “Why should fascists have all the fun?” The internet is a sewer, and art is too.

*

An artist makes two artworks, titled “Colored Sculpture” (2016) and “Black Sculpture” (2017). The former is a white, red-headed boy puppet repeatedly dropped and dragged by mechanized chains; the latter, an inert, editioned version, painted matte black. It’s hard to believe that an artist as perceptive as Jordan Wolfson would blunder into such a racially charged pair of titles. More probable is that the word colored is simply another layer of provocation.

Yet Wolfson doesn’t discuss his intentions—with this work, or any others—other than to say his intention is to make an artwork. So he does, and whatever the viewer sees in the work is their problem, not his. “I’m not my art,” said Wolfson at a presentation of his videos. “I let the world pass through me, and then it takes a shape.”

This distinction is troubled by Wolfson’s tendency to voice his animated characters and animatronics himself. “My parents are dead…I’m gay,” says “Female Figure” (2014), his impaled pole-dancing robot. (They’re not, and he’s not.) In the 2012 video “Raspberry Poser,” among cheerful animations of the HIV virus dancing to a Beyoncé track, Wolfson himself appears dressed as a crust punk, humping the ground and wearing blackface. The artist’s work features a stream-of-consciousness first-person that is meant to be understood as a persona. Rather than any specific ideology, the work is guided by intuition, inspiration, and the ambient world.

Where viewers object to his work’s spectacular violence, Wolfson professes an almost Koonsian acceptance. (If Jordan Wolfson came from Jeff Koons, then why is there still Jeff Koons?) “The thing about these artworks is that they’re always about a distorted form,” Wolfson has said, “but the distorted form is just an external factor, and inside that is the intention behind the work. And the intention is a very positive one—all the works have very positive intentions behind them. They're not about hatred and they don’t propagate hatred.” It is a privilege to disavow your work’s effects.

Conversely, it’s also a privilege to own up to your privilege, such as it is. In the 9th Berlin Biennale, Amalia Ulman exhibited a suite of videos pulled from her Instagram account that show her modeling designer shoes or cradling her pet pigeon. The installation was titled “PRIVILEGE.” A concurrent piece, in which Ulman faked a pregnancy on her Instagram, is also called “Privilege” (2016). One post is a classic Poe: The artist is pictured in a white dress shirt and tie. One hand jauntily holds a suit jacket, the other touches her “pregnant” belly. “I finally did it,” says the caption. “I’m finally part of the problem.”

Ulman’s first Instagram performance, “Excellences & Perfections” (2014), tricked many of her followers (and a few real-life friends) into thinking she’d gotten plastic surgery. Ulman has since publicly revealed that both pieces were acts; even so, there remain those who were shocked to learn the artist’s pregnancy was a fiction. Her put-on of privilege was excessive, but believable.

Part of the dissonance seems to lie in the ethos informed by the internet’s culture of freely mulching, remixing, reposting, and appropriating—methods that find rich expression both on the web and in the similarly “virtual” spaces of white-cubed exhibitions and artist studios.

In the culture at large, the perhaps old-fashioned notion that an artist should be responsible for their work's content nonetheless persists. On the internet, meanwhile, images have lives of their own. Meanings accumulate as they move; they grow abstract. Artists can disavow any interpretation their work receives. Thus, perhaps, Wolfson’s nonchalant use of racial codes, and Ulman’s comfort elevating a gentle troll into performance art.

Yet, unlike the high cycles of the web, art world circulation leaves artists a degree of authorship. This, in turn, leaves them open to responsibility for even unforeseen reactions to their work. Recent examples abound. Where Poe’s Law prevents any consensus over a controversial work’s meaning, and even peels meaning away from the artist’s intent, this hasn’t stopped artists, from Frances Stark to Dana Schutz, Kelley Walker to Sam Durant, from facing hard questions. Yet this shouldn’t be mistaken to mean that an artist is powerless to control their work’s reception; when Durant’s “Scaffold” (2012), a full-scale conglomeration of historical gallows, gave offense to the Dakota Sioux when it was installed at Minneapolis Sculpture Garden this summer, he had it dismantled.

*

Perhaps some artists really are oblivious to certain common interpretations of their work. Perhaps others are simply indifferent to their work’s reception. But it’s more likely that the savvy artist recognizes some value in perpetuating art’s inherent ambiguity—especially when said ambiguity is deliberately, morally provocative.

Who would admit that their artwork was designed to press precisely this sensitivity in a particular kind of viewer? Indeed, when artists telegraph their politics, the work can calcify. Better an amoral or offensive artwork, it seems, than a didactic one.

The ambiguous artwork might also enjoy wider circulation than the placidly candid. Like a clever Poe, it holds an audience on all sides of an issue, from those who enjoy the satire to those who love the sentiment—whether they find in New Eelam a killer app or a wicked sendup of the sharing economy. This is the position argued, from many angles, by a range of postmodern artists and writers.

Thomas Lawson proposed in “Last Exit: Painting” (1981) that an ambiguously political formalism might be the only delivery vector left to subversive art. David Joselit’s After Art (2012), taken up by both DIS and Thomas, argues that artists should embrace their participation in networks and circulation, including the capitalist kind.

“There’s a great quote by the director of the Christian Coalition, who said that he wanted to be a spy,” said Felix Gonzalez-Torres, whose understated homosexual desire, embodied in pairs of synchronized clocks and billboards of an empty, unmade bed, elude and thus haunt the viewer. “‘I want to be invisible,’ he said, ‘I do guerilla warfare, I paint my face and travel at night. You don’t know it’s over until you are in the body bag. You don’t know until election night.’ This is good! This is brilliant!”

Fungible and transactional, like a meme you can buy and sell, visual art is especially well-positioned to imbue the ordinary with some sense of threat. “I want to be a spy, too,” said Gonzalez-Torres. “I don’t want to be the enemy any more. The enemy is too easy to dismiss and attack.” In this sense, it’s productive not to know what the author believes. Or, more cynically, a pliable neutrality helps art circulate in a system willing to overlook all plausibly deniable extreme views.

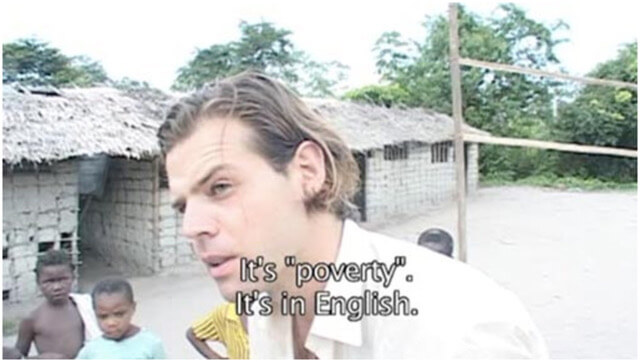

The notion of post-critical or nonjudgmental art has a not-so-distant corollary in the post-ideological ambitions of neoliberalism. It’s strange to see the ease with which certain artists, frustrated by the old ways, swap leftist problematics for the equally well-worn problematics of the free market. Some, like Thomas, or like Renzo Martens, explicitly claim to work toward social good, but do so by explicitly embracing arguably exploitative, practically colonialist methods. (“In Thomas’ work,” writes Ugelvig, “the future of the political Left lies in a mutation of capitalism’s own accelerated state of being. This, of course, is no small proposition and contains its own set of ethical conundrums.” What these conundrums are he does not say.)

Few projects exemplify Poe’s Law as completely as Martens’s “Episode III: Enjoy Poverty” (2008), in which the Dutch artist tries to help impoverished Congolese monetize their own poverty. When this fails (as, presumably but not admittedly, the artist knew it would), he leaves them with art instead: a flashing neon sign that reads, in English, PLEASE ENJOY POVERTY.

Martens’s current project, Cercle d'Art des Travailleurs de Plantation Congolaise (The Congolese Plantation Workers Art League), takes the next logical step; through a combination plantation, land trust, and kunsthalle, local farmers will earn money by selling chocolate sculptures in the western art market. Martens plans to improve the lives of his collaborators by leveraging his art-world privilege in order to literally gentrify the jungle.

The assurances of the artist aside, uneasy questions remain. Is CATPC designed to actually elevate Martens’s subjects? Is it a ploy to outline the contours of art’s failure? What does Martens truly think he’s doing? But the point is he is doing something. The artists under discussion here proceed from the idea that there is no outside, no alternative, no pure position, and that any efficacious critical stance will therefore be positioned inside.

Consumerism, colonialism, libertarianism, communism; a selection of yesterday’s dire -isms form the ambiguous facets of today’s avant-garde. According to Poe’s Law, the most extreme example of capitalism comes to resemble its own satire—and vice versa. In what sense is accelerationism a satire of capitalism? In what sense is it its final form? The effect is the same: an ambiguous suspension of belief.

Perhaps once we could say that the default mode of art is sincerity; others have argued that our moment is marked by a “new sincerity,” characterized by equal parts irony and sincerity “combined like Voltron.” But on the internet, culture increasingly skews to satire. Where art exists between an honest story and a troll, the savvy viewer assumes that one never knows for sure. And the savvy viewer will respond as if it could be either, as if it’s both at once.

Suspended in this ambiguity, one can see how artist and viewer alike might turn toward the post-critical and the post-ideological. It would certainly be convenient to rephrase art’s moral contradictions as active dialectics. Thus the fact of art comes to seem as self-evident as the abstractions of the market, which is thought to tend, rationally, eventually, toward the best possible result.

Meanwhile, guided partly by a pragmatic acceptance of the world as it is, partly by an almost genetic drive to see their work circulate, the artist feels free to act like the Thatcherite entrepreneur, the TINA Man, for whom There Is No Alternative. Such an artist finds the justification of their work beside the point. Trolling or not, they may be right.