Snapping in Chinatown

Margaret Lee

October 26, 2017

.jpg)

In Living a Feminist Life Sara Ahmed describes the “feminist snap” as a breaking point. “You can snap because you are exhausted by having not snapped thus far and by what you have had to put up with. You can’t bear what you have borne for too long.” It’s been a traumatic year and I, like many, have been trying to avoid said snapping.

But at a protest on October 15, where around 50 people gathered to peacefully speak out against an Omer Fast installation that embodies the tired, colonialist view of Chinatown as a place of filth, I reached my breaking point. I witnessed an older white male, upon exiting the exhibition, manhandle an Asian protestor, shoving them out of his way. James Cohan Gallery employees stood by and did nothing. I snapped.

The high profile sexual harassment revelations have led to a huge amount of rightful snapping. I have profound respect for every person who has bravely come forward to share their story. They have kicked down the door, sent the call. We must tear down the houses of patriarchy that protect the abusers of the world. But in this moment of empowerment, we must not overlook the fact that sexual violence cannot be eradicated in its entirety unless we also tear down the racist, colonialist structures that allow for such abuses.

As we move forward with #metoo and #Ibelieveyou, let’s not forget this applies to all who speak out against injustice and violence. We must support those who go beyond simply pointing a finger, those who generate viable alternatives.1 We cannot allow these people to be blacklisted, gaslit, or to have their arguments invalidated with ambiguous PR speak. We can no longer passively witness the coopting of struggles and labor.2 And we especially cannot call these voices censors. This collective action is the result of the multitude of snaps and these snaps cannot be silenced.

To speak about Omer Fast at James Cohan Gallery, we need to speak about Otherness. Audre Lorde considers racism, sexism, ageism, heterosexism, elitism and classism together as an apparatus of “isms” that produces superiority and the normative right to govern anything lesser.3 She defines the mythical norm of U.S. culture as “white, thin, male, young, heterosexual, Christian, financially secure.”

I will update her definition to include cis, clean, well dressed, and groomed. All those who fall outside of the norm are labeled Other, and are subsequently dehumanized. This Otherness allows those who align themselves with the normative “order” to justify their use of violence in order to civilize those they see as “savage,” or without civilization and culture.

The United States, and indeed the Americas, were founded with the genocide and rape of Indigenous and African peoples. On stolen land, enslaved people produced the wealth that has propelled the United States to its position of global power today. European colonizers justified mass acts of violence against Indigenous and African peoples by legally defining them as subhuman. These legal justifications for state violence are present today, yet their explicit racial language is obscured; through praxis, these laws become common discriminatory attitudes that justify further violence. We occupy stolen land, while slave labor continues in the prison-industrial system.

Native American/First Nations/NDN/American Indian/Indigenous women in the US experience some of the highest rates of sexual assault in the country. To quote Lisa Brunner, rape survivor advocate and member of the White Earth Nation, Minnesota, “I call it hunting—non-natives come here hunting. They know they can come onto our lands and rape us with impunity because they know that we can't touch them.”4

So what does this have to do with Omer Fast at James Cohan Gallery? Historically, U.S. national identity has been defined by the systematic delegitimization of Others. And today, we witness a frightening growth of interests who push for regression; they specifically invested in dismantling the progressive values so many have fought to create. What happens when fringe groups that posit White Christian values as what it takes to “Make America Great Again” grow large enough to elect a sexual predator into the highest office of power?

We get throngs of White Nationalists, emboldened by our racist president, chanting “You will not replace us, Jews will not replace us,” in Charlottesville. This type of vitriol is passed down the generational pipeline because all too often, too many people turn a blind-eye to the “isms” Lorde catalogues, oftentimes actively sanctioning (and perpetuating) the bigoted stereotypes needed to justify violence against Others.

In a statement, James Cohan Gallery equated Chinatown Art Brigade’s protesting of the exhibition to censorship. I would argue that the protest was instead a defense of the dignity of people who have borne the burden of being historically marginalized as Other for too long. To quote Chinatown Art Brigade (CAB), who led the protest5 against the gallery along with Decolonize, Mother’s on the Move, Occupy Museums and Art Against Displacement (AAD).

The conception and installation of this show reifies racist narratives of uncleanliness, otherness and blight that have historically been projected onto Chinatown. We cannot underscore enough how offensive this is to the people who live and work here. The artist’s choice to ignore the presence of a thriving community filled with families and businesses reduces their existence to poverty porn. This has a real and negative impact on how Chinatown is perceived by non- residents, politicians and developers who view low-income communities as wastelands ripe for investment and exploitation.

Full statement here.

Furthermore, Fast’s installation reiterates and perpetuates the colonizer’s gaze that views the bodies and communities of people of color as essentially dirty, impoverished, and unworthy of respect. Is it a stretch to interpret the manhandling of a peaceful Asian protester as being directly related to this colonial history? The disdain and lack of respect preceding the violence was unmistakable. I’m sure the perpetrator of this violent act would argue that he had no other choice but to push his way out. I will not support this assumption. One always has a choice, and violence is never accidental.

The term censorship derives from the official duties of the Roman censor who, beginning in 443 BC conducted the census by counting, assessing, and evaluating the populace. Originally neutral in tone, the term has come to mean the suppression of ideas or images by the government or others with authority. So by this definition, censorship is a form of prohibition or punishment that comes from above—i.e., a ruling power or law.

For James Cohan Gallery to allude to CAB’s action as censorship (and for the gallery to imply that CAB and the protesters are violent forces of intimidation) is akin to Woody Allen’s response to the Weinstein revelations—calling it “tragic for the poor women” while warning against a “witch hunt atmosphere.”

CAB and the other protesters were not censoring, we were exercising our first amendment rights, and making our democracy stronger by doing so. To imply otherwise demonstrates the gallery’s lack of understanding of their institutional power and their relation to their community. And to clarify, CAB referred to Omer Fast as “a non-US and non-New York artist” only to highlight that he does not live in Chinatown and not an engaged member of the community. For an outsider with little or no knowledge to say he is presenting an “authentic” version of the gallery pre-gentrification, to which the artist necessitates the inclusion of trash and squalor is, to quote Holland Cotter, “nasty condescension.” Cotter continues:

“And, really, can a portrait of a 'lost' ethnic neighborhood as a study in tawdry dysfunction read any other way? Not in the class-and-wealth co-opted New York City of today.”

That Omer Fast’s racist, colonialist gesture is being publicly supported and defended by James Cohan Gallery makes clear the lack of understanding of their own privilege working in a neighborhood that is populated by predominantly low-income people of color. When questioned by these residents, their insistence upon their own innocence and superiority is deeply embedded in an unspeakably violent, patriarchal, elitist, and colonial history—one they actively and willfully reproduce today. Their defense is as hurtful as their actions.

And so, I snapped. Yet one snap is not separate from another. To all who have shared your pain—whether caused by multiple combinations of racism, sexism, classism, cissexism, ageism, ableism, misogyny, homophobia, transphobia, etc.—I thank you for having the courage to speak out. And to all of us in the art community—we must use our creative talents and intellect to create more understanding and peace, not less. We cannot stand by and allow artists to use marginalized peoples’ lived experiences as thought experiments or identity tourism.6 We cannot allow artists to utilize lazy, unintelligent gestures and ambiguous language to evade acknowledging that one’s actions can be racist and hurtful even with the best intentions. We are smarter than this.

We need to encourage others in our community to rise to the challenge of becoming capable of holding a multiplicity of voices. Though I am addressing a hyperlocal incident, there are countless other examples. Each is reason enough to work together in the fight against the perpetuation of negative stereotypes and the silencing of people who speak out. Let’s remember the underlying commonality of these experiences. Inherent bias does not appear out of nowhere; it is the perpetuation of demeaning representations coupled with the continued denial of marginalized peoples’ right to self-determination.

We are all at a breaking point. Let’s not miss this opportunity pick up the pieces and create something critical and compassionate together.

I’d like to thank Harry Burke, Howie Chen, Tenaya Izu, Ajay Kurian, Young Jean Lee, Mithra Lehn, and Oliver Newton for giving me feedback, encouragement and editing assistance. I rely on my community to continue to challenge me and hold me accountable and for that I am eternally grateful.

- http://www.e-flux.com/journal/58/61168/so-now-on-normcore/

- That the gallery kept up the protest posters but not the full Chinatown Art Brigade statement is extremely problematic.

- Audre Lorde, "Age, Race, Class, and Sex: Women Redefining Difference," in Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches (Freedom, CA: Crossing Press, 1984), pp. 114-123.

- http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/features/2013/03/201334111633172507.html

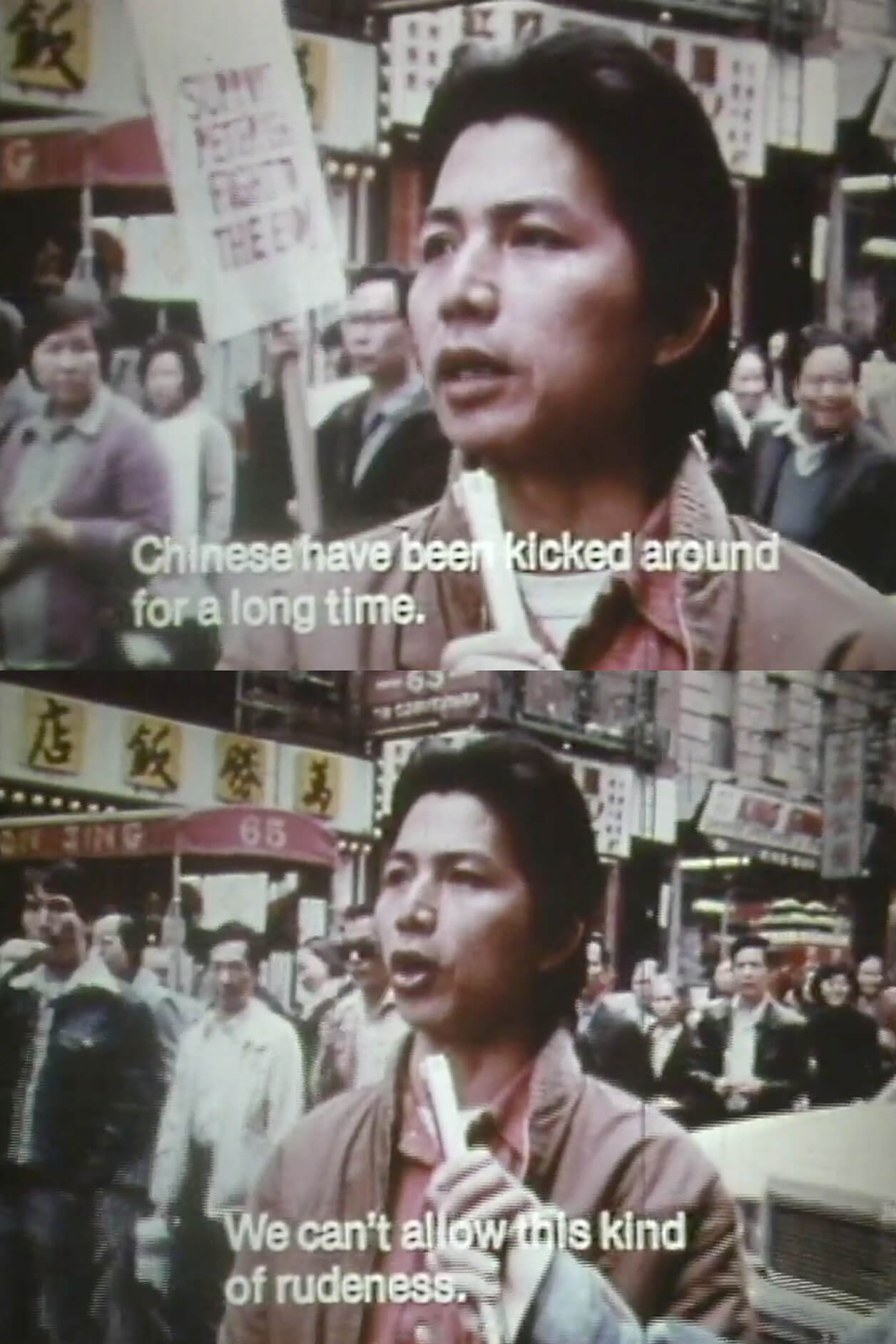

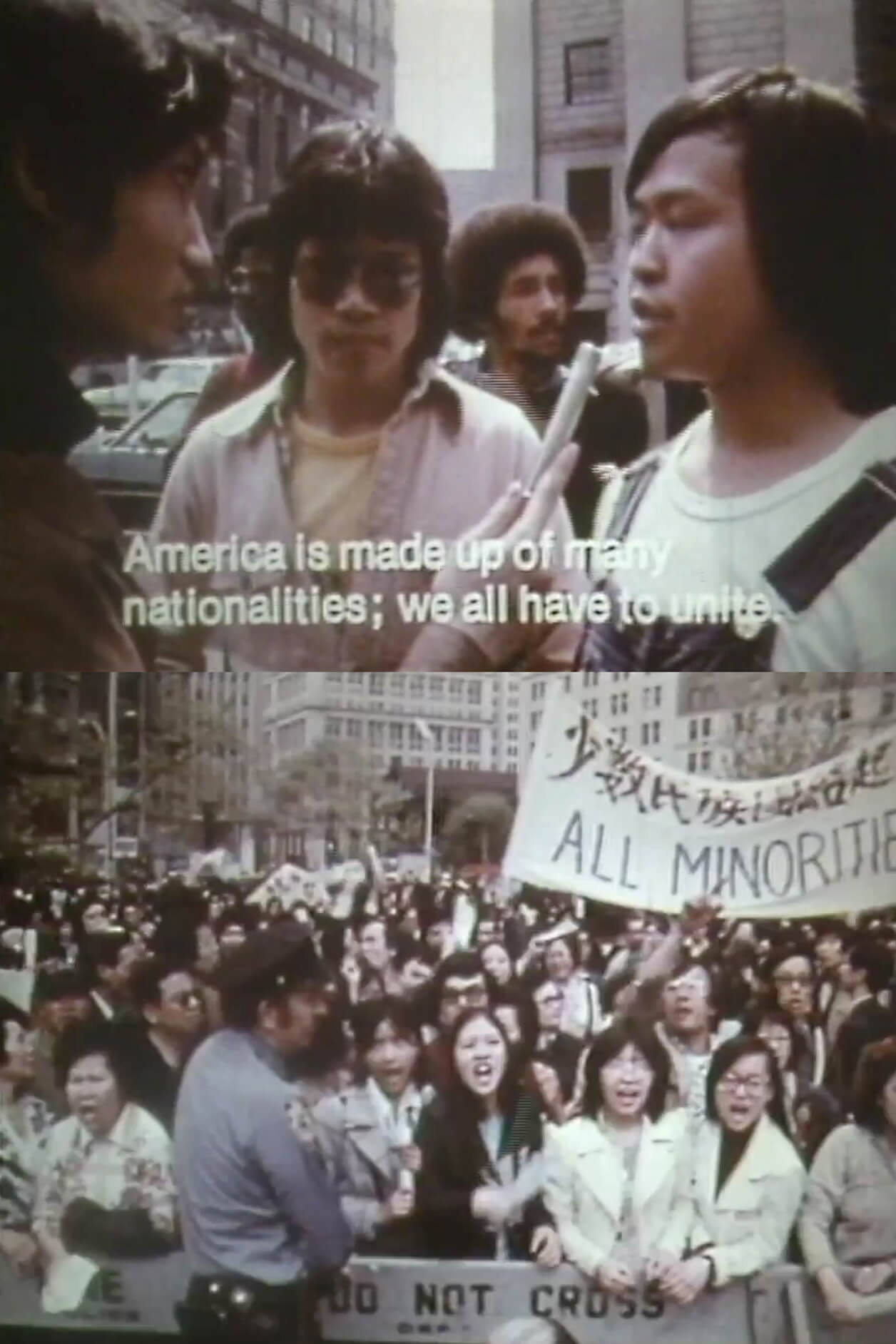

- To add some perspective, there is a long historical precedent of Chinese-Americans coming together to fight for social equality. I highly recommend watching Christine Choy’s 1976 documentary From Spikes to Spindles, which traces the roots of racism towards the Chinese in America and shows how the NYC Chinatown community has galvanized over the years since the 1874 Exclusion Act, to not only protect each other but stand in solidarity with all discriminated people. CAB’s action adds to this legacy. It’s comforting to know that empowerment and solidarity can also be passed down the generational pipeline.

- http://brooklynrail.org/2014/05/art/one-step-forward-two-steps-back-thoughts-about-the-donelle-woolford-debate