Is the Club a Political Unit?

Rob Goyanes

September 11, 2017

“It was the music... It made you do unwise disorderly things. Just hearing it was like violating the law.”

-Toni Morrison, Jazz

I’m not so sure what led me to the giant warehouse in Brooklyn—a location kept secret until the day of the rave, held within an emptied skeleton of industrial capitalism—but it had something to do with the darkness it promised. Some sort of cover from normal society.

A couple hundred people, sweaty and heterogeneous, moved amongst the ambient red lights, the slow strobes, the plume of fog that hovered over the dance floor before being sucked outside through the bay doors. Everyone was enveloped in the modulating synths, claps lightly reverbed, and tightly-wound kicks. Some were alone, some with friends or lovers, most among strangers. A few of them seemed a little sad despite their swaying.

Look at it poetically and everybody there was a discrete morphological unit, an expressive totem of their personal truth-as-movement. Anthropologically, they were a swarm of different races and genders and genres, all doing this really strange human ritual we call dancing. From a judicial point of view, they were breaking the law: out of the tens of thousands of drinking and eating establishments in New York City, this was not one of the 88 that has a Cabaret License.

The Cabaret Law—which amounts to a ban on social dancing in bars and restaurants without the license—has a long, variegated history. At times, it’s been weaponized against subcultures; at others, barely enforced. Olympia Kazi, a member of the NYC Artist Coalition, says that the Cabaret Law’s loose enforcement is exactly where the peril lies. “The reports I’ve heard, especially from DIY venues, is that whenever they’ve had a hip-hop show that’s more likely to attract African American youth, then they will get the NYPD at their door.”

The Cabaret Law is just one manifestation of a framework that is meant to police black lives and other unwanted cultures, starting with black and interracial clubs in 1920s Harlem. With fascism and anti-fascism ascendant once more today, there is a new challenge to the law, one that seeks to mine its historicity and offer political alternatives. The campaign against the Cabaret Law is tied into the larger narrative of resistance against the far-right, and dancing in New York is intimately conjoined with the identity politics and economics of every cultural era, from jazz to techno. But merely repealing the law will only be a small victory for proponents of the freedom of dance, and of freedom itself.

*

The dancers in that Brooklyn warehouse are just a contemporary apparition of New York’s long history of dancing. In fact, they might be a somewhat reserved lot compared to those of years past. In his book Low Life, Luc Sante describes the inhospitable warrens of 19th-century tenements converted into wild social clubs for ragtime and folk ragers; the saloons slinging whiskey to raucous motleys of fat cat financiers, pimps, sex workers, gangsters, and freshly arrived immigrants from countless nations. Unlike the mostly freestyle movements of dancers today, these humans were doing structured dance crazes, “the bunny hug, the grizzly bear, the turkey trot, the one-step, and that import from the slums of Buenos Aires, the tango.” Sante makes clear the fact that from the 1890s to the 1920s, you could dance at nearly every restaurant in Manhattan, such as the midtown Chinese boîtes, the small restaurants that hired jazz bands to play during dinner, as well as the innumerably sloppy, dirty spaces where people drank and danced and fucked till dawn.

In the early 1920s, hundreds of thousands of southern Blacks, Africans, and West Indians moved to Harlem for the promise of industrial labor, and the neighborhood became an epicenter for jazz, a genre that challenged colonial chord structures, tonalities, and premeditated song with its emphasis on the blues, polyrhythms, and improvisation. The dancing reflected the music, and both were decried by many white critics as insidiously sexual and primitive. Jazz, the first black culture to be mainstreamed for consumption in the United States, was both a threat and sublimated desire for white America: white people couldn’t get to Harlem fast enough to let loose their inhibitions and dance along to something sonically new.

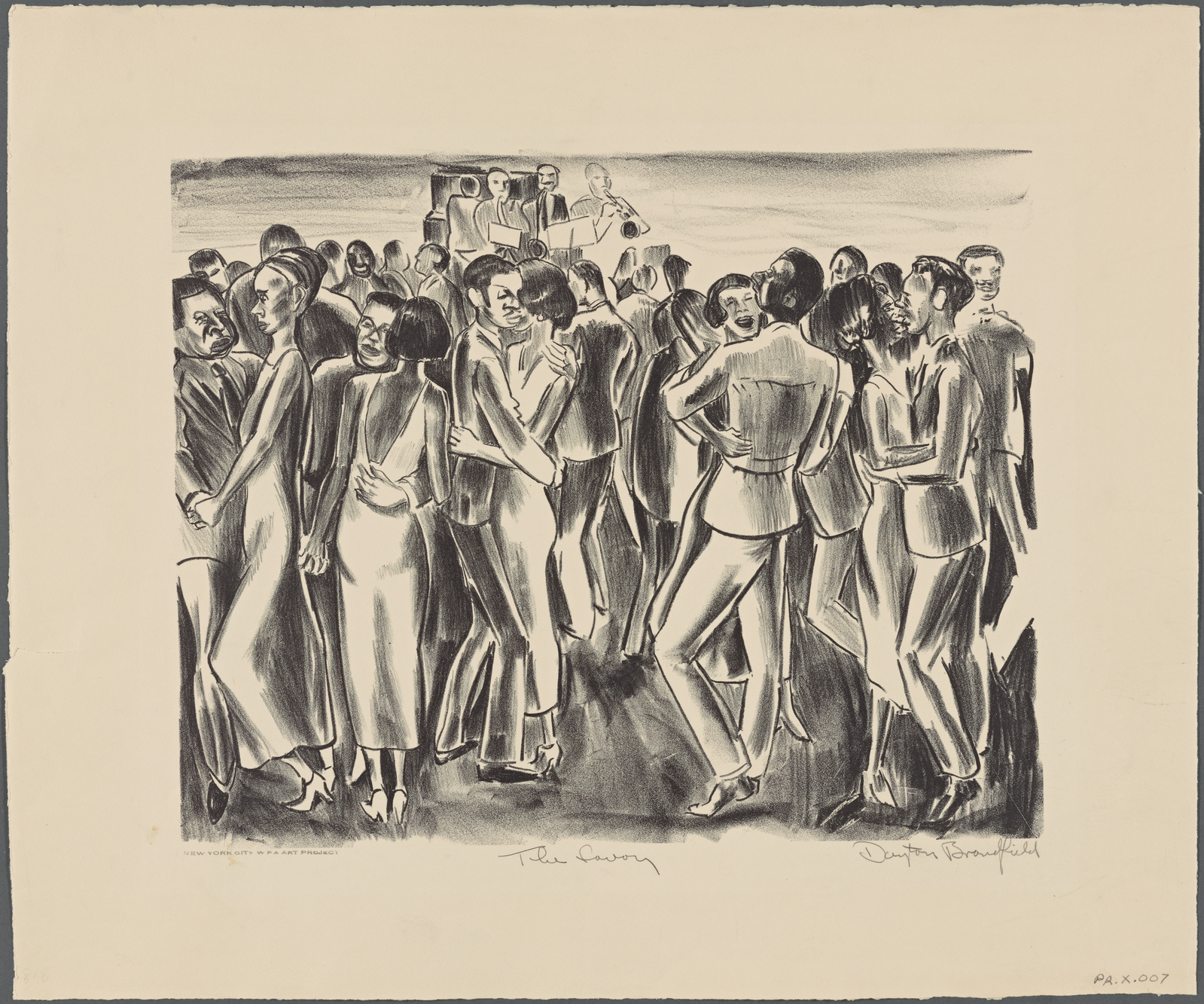

The spaces for jazz and dance parties in Harlem varied. Rent parties were held in overcrowded tenement apartments and smoke-filled basements as a form of black community gathering and fundraising for rising rents, while the jungle-décored Cotton Club featured Duke Ellington and Louis Armstrong playing for a whites-only audience. However, as Paul Chevigny notes in his book Gigs: Jazz and the Cabaret Laws in the New York City, “most of these Harlem clubs were among the few places in a segregated society where blacks and whites could mix.” Some clubs were designed as lavish, refined commercial establishments, such as the Savoy Ballroom, while others (the Onyx, Lenox Lounge, The Famous Door) served as haunts for musicians to experiment with their craft, play for each other. This being the time of Prohibition and segregation, New York’s corrupt political machine was quick to take notice, as it continues to do.

Starting in 1926, the Cabaret Law and a web of other nightlife regulations were enacted by Mayor Jimmy Walker, contradictorily so, considering the fact that he was known as the “Duke of Jazzland” and “Night Mayor of New York” because of his predilection for nocturnal carousing. In its original form, the Cabaret Law made dancing illegal at any establishment without a cabaret license, banned wind and percussion instruments, and held a “three-musician” rule (no more than three to a stage). It specifically targeted jazz performed at smaller, interracial clubs in Harlem. As scholar Sara Ramshaw notes in her book Justice as Improvisation, the Cabaret Law was not applied to hotels of more than 50 rooms, premises owned by membership corporations, or religious and educational institutions. In other words, establishments with large amounts of capital and political influence, most of which were controlled by whites.

In 1940, after the more aggressive swing and quickened BPM of bebop emerged, the NYPD police commissioner imposed further regulations, including identification cards for cabaret employees and then, in 1943, for musicians. Police started fingerprinting and photographing those who worked in licensed places, and denied cards to those who had legal trouble or who were considered of “bad character” (i.e. black). The 1940s and '50s were a difficult time for jazz artists: Billie Holiday, who had been targeted by the Federal Bureau of Narcotics since the late 1930s, was convicted of a narcotics charge in 1947, and in 1948 she was denied a cabaret card. Unable to work and secure gigs around the country, she continued to suffer from bad health and harassment by the police, and died of liver and heart disease in 1959. She had been handcuffed while on her deathbed. In 1951, Charlie Parker had his card revoked, and though it was reinstated in 1953, he was seen as unemployable. This, compounded by his deep heroin problem, contributed to his death in 1955. These are just two high-profile stories amongst thousands.

After years of agitation by performers of all colors, the card system was dismantled in 1967, and finally, by the 1980s, so were the bans on certain instruments and the three-musician rule. Dancing continued to change as music, economics, and society made their shifts, while the NYPD and state agencies of New York, “the city that never sleeps,” selectively enforced the Cabaret Law and other nightlife laws as a means of accelerating gentrification, policing minorities, and shutting down establishments that didn’t fit the state’s cultural vision and policy of capitalist expansionism. Besides black and brown clubs, raids on gay nightclubs accelerated as the spaces went above ground, which was met by a newly vigorous, riotous response in the form of Stonewall.

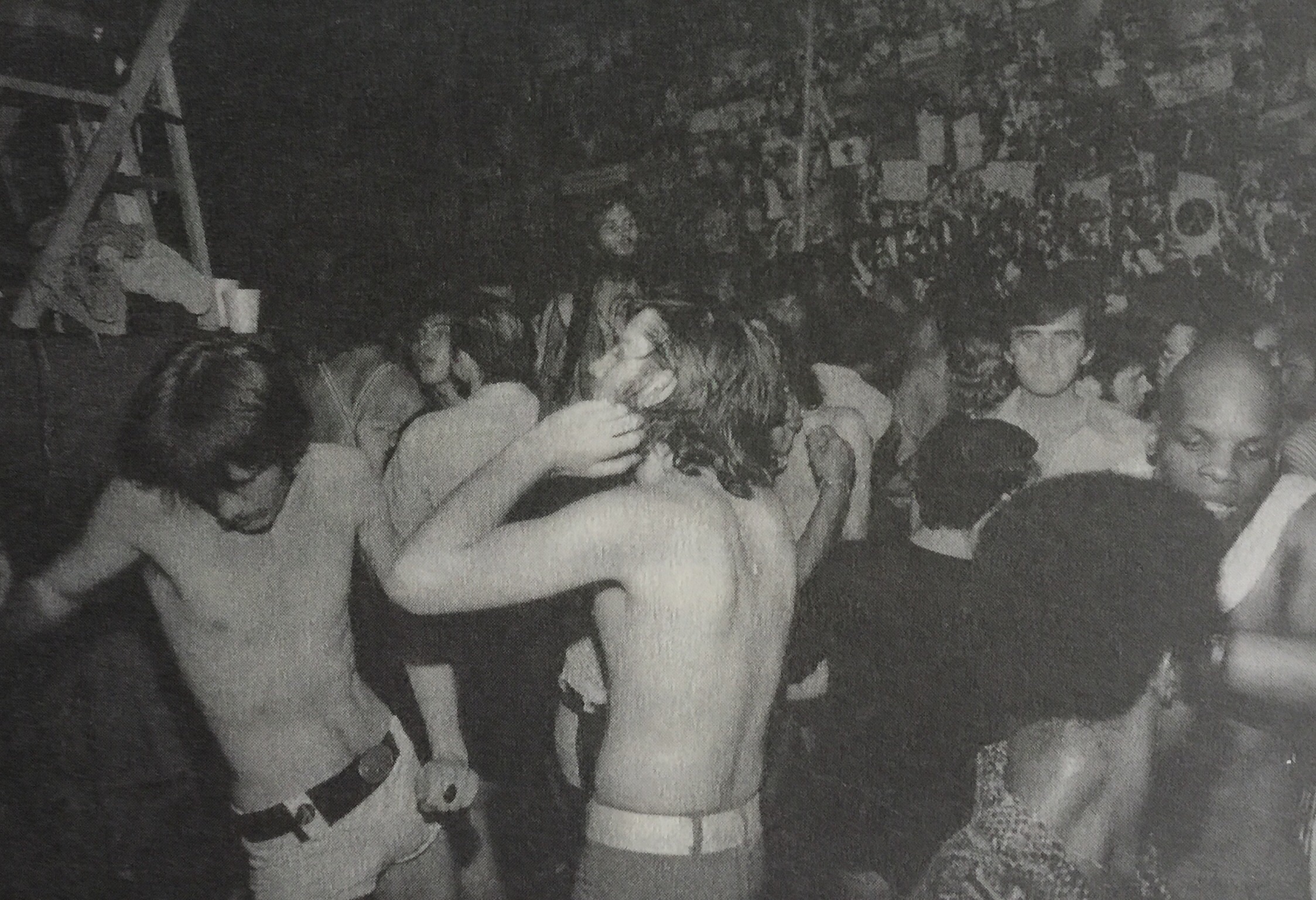

Disco emerged in response to the guitar-driven psychedelic rock of the 1960s, using a four-on-the-floor beat and conglomerating elements of black and brown music genres (funk and soul and salsa, etc.). The 1970s—a time of federal deregulation and cocaine and self-indulgence as much as it was a time of leftist political awakening—saw the rise of D.J.s and the new formal musical method of mixing. Inspired by Parisian discotheques and the free love social model espoused by the hippies, David Mancuso started having parties at his apartment, which came to be known as The Loft, in 1970. Besides the aesthetic functions of utilizing synthesizers, fading guitars into the background, and encouraging a globalist musical palette, these events served as political refuge. The gay and queer community, as well as many a wild and outcasted freak, all of whom were intimidated and assaulted at both nightclubs and daytime establishments, found what would become a model for the community-centric music underground.

The Loft was pluralist in both sound and species: the crowd was multiracial, a panoply of sexual identities, a mix of upper and lower classes, all dancing in one, tall-ceilinged room bejeweled in discoball droplets and adorned with balloons. This was no utopia, a space still plagued by the ups and downs of any social scene or party culture, but it did come with an egalitarian purpose. Attendees were there to hear not just disco, but also jazz and calypso and classical, all on a high-fidelity sound system. As Tim Lawrence notes in his book Life and Death on the New York Dance Floor, “The Harlem rent-party tradition that dated back to the 1920s suggested a community-based model of unlicensed, private partying that could be sustained by donations. The civil rights, gay liberation, feminist, and antiwar movements fed into the rainbow coalition identifications of [Mancuso’s] come-as-you-are crowd.”

The Cabaret Law was loosely enforced in the anarchic '70s and '80s (Mancuso was told by the Department of Consumer Affairs that he needed to obtain a Cabaret License, but eventually won the right to keep hosting dance parties since he didn’t sell food or booze). The early 1980s saw an explosion of multivalent cultural activity and its concomitant dancing. Black-clothed and mohawked bodies smashed together to the angry angular rhythms of punk and hardcore, while spandex stretched and stilettos grooved to post-disco and conceptual art rock. In his book, Lawrence reminds us that the '80s community-driven music and dance cultures were reactions to Reaganism, rental inflation, and the broader shift to postindustrialism and finance capitalism. A similar cultural moment is happening today.

*

New York, home base of the incoming Neoliberal era, was becoming a truly 24-hour apparatus for the monied class. Culture, and the way we move our bodies, changes with the tides of oppression, criminalization, and efforts at resistance and liberation. The late '80s and early '90s saw the emergence of hip-hop and rap, which came with a politicized message against police brutality and economic disparity, and the formalization of dance forms that again challenged the status quo stiffness and supremacy of white movement. This wave of black cultural innovation—like the jazz of the 20s—was met with a new crackdown by the state when Rudy Giuliani came to power in 1994. Other minorities were targeted as well.

Giuliani’s pursuit of a “Quality-of-Life” platform, the contours of which included a massive expansion of the NYPD, turning Manhattan into a fortress for the bourgeoisie by targeting the homeless, and a revival of the Cabaret Law as a means of targeting clubs, specifically LGBTQ and non-white clubs. As Eli Kerry and Penn Bullock point out in an article for Thump, the gay clubs of the East Village and Latin clubs above 59th street suffered the most. It’s important to note that this was also a time when hundreds of thousands of people were being diagnosed with AIDS, and conservatives (and many liberals) sought to punish the gay population.

Fiona Buckland, in her book Impossible Dance: Club Culture and Queer World-Making, highlights the fact that in 1997, the year of Giuliani’s re-election campaign, he and the police commissioner specifically targeted dance clubs, claiming that there was a link between them and the crimes he sought to eradicate. The underlying impetus, however, was a racist strategy for sanitizing urban space—and it was a remarkably successful one, but not totally.

From the 2000s on, music and dance culture in New York has blended into a digitized hybridic machine, and in many cases, has gone underground, like every era before it. Though formal boundaries still exist, contemporary club culture in New York reflects the sundry interests of a populace plugged into the internet. In the spirit of club-cum-gallery-cum-activist space, DIY and mid-size venues have organized to bring together musicians and audiences from across social and generic spectrums. Rather than the structured dance crazes of the modern era, freestyle is the dominant paradigm, cannibalizing what’s come before, and imagining what lays beyond, what’s possible for the human body. In many cases, people just dance because they’re drunk or high, or because moving around feels good.

These present-day spaces contain a wide range of qualities, as the jazz clubs of the '20s: some are held in dirty smoke-filled basements fitted with illegal bars behind black curtains, or in pastiche metalhead joints adorned with Iron Maiden and Megadeth paraphernalia. Many contain a refined, non-confrontational, boring indie-ballroom aesthetic. There are goth dives, R&B ballrooms, Chinese restaurant raves next to Wall Street, warehouse-loft punk dens, tucked-away Mexican joints blasting boleros, Koreatown karaokes.

Some clubs openly engage with politics—the major social axes that are defining our current moment—while others just remain focused on entertainment and fun, places for a night out.

*

In 1990, an arson fire at Happy Land, an unlicensed club in the Bronx, killed 87 people. As a result, New York officials formed the Multi-Agency Response to Community Hotspots (MARCH) with the goal of ensuring safety and acting as a liaison between residents and nightclubs. However, MARCH also appears to be pursuing raids on clubs in an effort to change neighborhoods. James Barclay, whose club in Brooklyn has been raided at least twice, describes it like this. “It’s usually about a dozen people that come in completely announced, they storm through the place, they turn the lights up. They got flashlights on everywhere and they write you a multitude of tickets, with the intention of shutting you down permanently.”

When I spoke to Barclay on the phone, I thought about the times I had danced illegally at New York’s clubs, occasionally looking up to see the “No Dancing” sign. All the times that people let go to the sonic miasma of techno and noise and pop and rap, the unnamed and unnameable genres being made and mixed by disaffected and passionate humans. “The majority of people in power in New York City have a very specific vision of the future,” Barclay said. “It doesn’t include places where people are dancing to reggaeton or techno or hip-hop or bachata.”

The radically-named Dance Liberation Network, a conglomeration of collectives, club owners, musicians, and artists, has led the drive to repeal the Cabaret Law. It represents an organized effort by cultural producers—including Discwoman, a platform that focuses on boosting the profiles of non-white-male musicians and DJs—to affect political change. And the effort is on the verge of success: Brooklyn City Councilman Rafael Espinal recently introduced a bill to repeal the Cabaret Law, which seems favored to pass.

A repeal of the Cabaret Law is undoubtedly important for anyone interested in dance culture and notions about freedom of movement. A ban on dancing is frivolous and oppressive, especially in a place in New York City, where people need to let off steam, and especially when the Cabaret Law is steeped in a history of racism and lopsided urban development. A repeal of the Cabaret Law doesn’t just ensure the freedom to dance: it also cracks the facade of who decides the larger, structural changes in neighborhoods, and how culture is intimately embedded within the process.

However, a legal framework for dancing is not the be-all and end-all. In August, the City Council approved the establishment of an “Office of Nightlife,” which is supposed to mediate the government and nightlife industry. Though regulatory mechanisms are necessary in a 24-hour city, one can’t forget that this office, like any office, has the potential to also be utilized as a tool for exclusionary politics. Important questions should be asked: Is an extra layer of governmentality really what’s needed? Does this mean a more automated night-life, a constriction of the radical potential that the night offers?

The slogan that’s been attached to the repeal effort is “Let NYC Dance.” Though the law should be changed, there’s also something to be said for not asking for permission, the way that so many dancers of years past had not. Dancing, and by extension, nightlife, refuses to be totally regulated, especially in a place like New York City, where an infinite, dimly-lit labyrinth of clubs, bars, warehouses, and spaces with a floor and sound system will continue to exist, despite the efforts to police them. Bodies will move how they please.

What drives humans into the night? For some, it’s just a respite from the drudgery of the day, or a desire to negotiate pleasure and risk. For others, it’s a means of empowerment, an assertion of social existence, a liberating, pleasurable moment of self-expression, a connection of the body to the sounds it so yearns. The night provides cover.