Epigraph/Epilogue

Claudia La Rocco

November 1, 2016

For Bill, and for Connie

“You missed nothing.”

That’s how the poet and critic Bill Berkson signed my copy of Invisible Oligarchs (Ugly Duckling Presse, 2016), a partial reproduction of the notebook he kept during a 2006 visit to Russia, augmented by correspondence with various figures and a pair of poems written after Pasternak and Pushkin. I didn’t understand its meaning and figured it was a joke I’d missed (not surprising, given the quickness of his mind), thus missing something twice.

When I read the book several weeks later, I saw that the line, reproduced in the final few pages, is the writer Kate Sutton’s response to one of Bill’s: “In haste to get to Kremlin we neglected the modern section across the street.”

Now I had the context, but the meaning still eluded. Why this particular line? Another thing I would love to ask Bill.

*

Where do people go when they attend readings, their bodies frozen in positions of thought, their eyes finding a middle distance, or closed?

I thought this while listening to Lucy Ives read from her beautiful new book, The Hermit, at a reading organized by the writer and San Francisco poetry lynchpin Kevin Killian in the not-so-large apartment he shares with the writer Dodie Bellamy, everyone cheek to jowl.

I often don’t like readings. Bad theater. But this one was lovely, both in form and content.

*

“You missed nothing” wouldn’t be a bad phrase to describe Bill Berkson’s life, if you were addressing Bill himself, who was born in 1939, in Manhattan, and died suddenly in San Francisco, from a heart attack, on June 16th. I knew him only for the last few years, long enough to feel keenly what his longtime friend, fellow poet-critic John Ashbery, wrote in Artforum: “As was the case with so many dear friends, he and I seldom spent much time in the same city or even country. They all seem emptier now.”

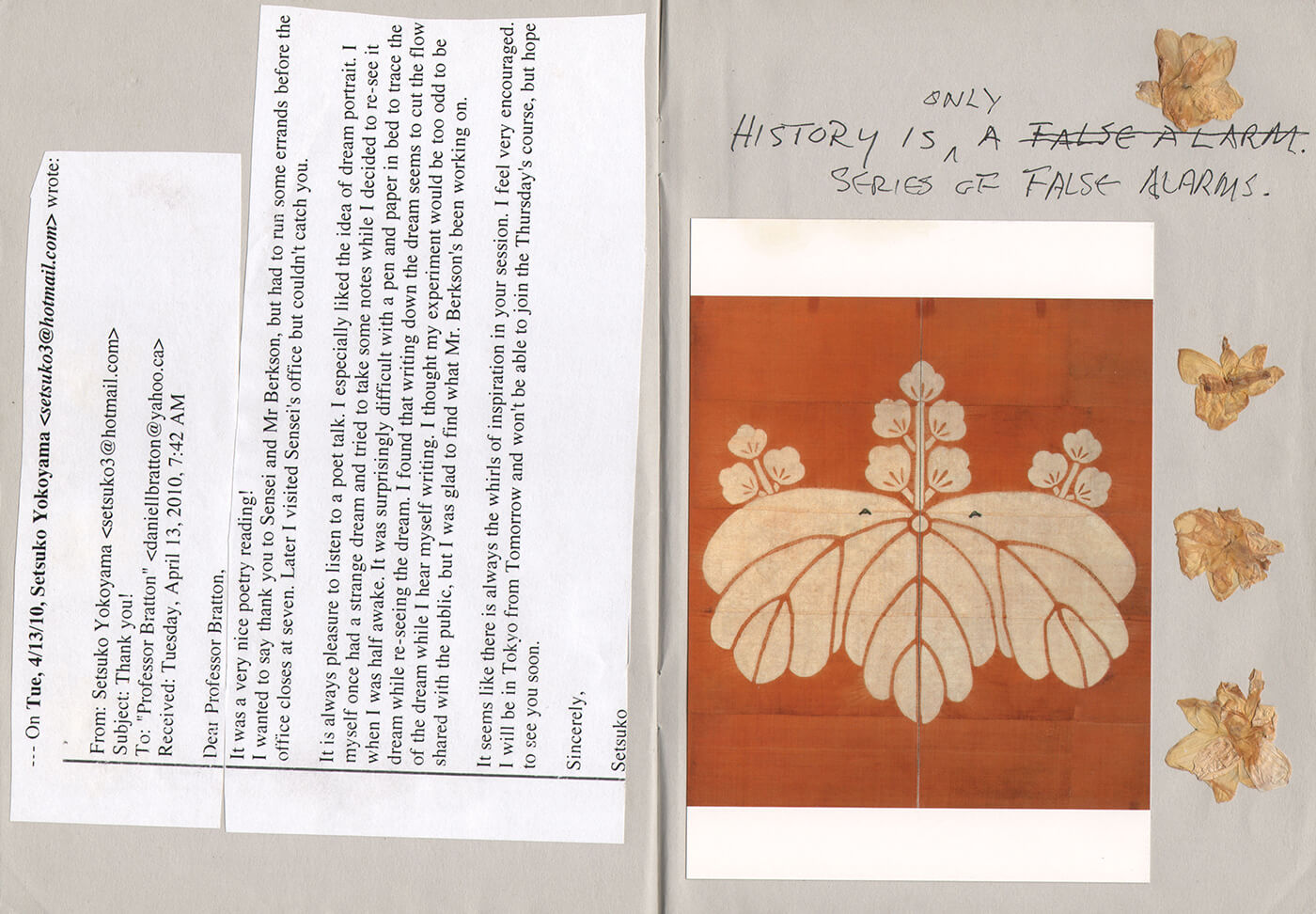

After Bill’s death, I realized that the last three books he gave to me and my boyfriend were all variants of travelogues and notebooks. Besides Invisible Oligarchs, there was Amsterdam Souvenirs (Blue Press, 2016), co-written with Joanne Kyger; and The Far Flowered Shore: Japan 2006/2010 (Cuneiform Press, 2013), a three-volume collection reproducing the two notebooks he kept on the trips indicated in the headline in handsome facsimiles, plus a typed transcript of his handwritten scrawls.

If the actual landscapes are emptier, the literary ones remain achingly full.

*

The news is unremittingly awful. Violence everywhere, and impunity.

I am in Boulder, Colorado, on the Fourth of July, having flown in to lecture at Naropa University’s Summer Writing Program. The air is hot, thin, and bone dry. I go with a friend and her family to Folsom Field, the University of Colorado’s stadium, to see the fireworks show. There is, we are told, a buffalo that runs around before the explosions—this sounds something rather more painful than exciting, but in any event it doesn’t happen, as the turf is covered by flooring from the previous event, a Dead & Company concert. No answer as to whether the buffalo’s run is canceled for her protection or the flooring’s.

The pre-show is forlorn, predictable: the animal mascots, the Teflon-like emcee, the local band covering hits of yesteryear amid feedback screeches. Cheerleaders skirt a line between children and pin-ups. Only the fireworks are sovereign, despite the too-loud nationalist pop songs underpinning them. They climax in a final, layered shimmering, as if a net of dense gold filigree had been cast about us.

After, as the stadium empties out, there are chants of “USA, USA,” an unadulterated statement of support that I cannot remember when last I fully embraced (I know I did at some point; the sentiment is not foreign). I am exhausted, thirsty, wishing for my own bed.

I will think of all this when, reading the 2010 section of The Far Flowered Shore, I come across these lines: “Watch Cheney and learn. Lies and every other shameful device, anything in the service of Empire, because there isn’t any. Nero on fire, Caligula gone bye-bye, Kaputt.”

*

We drive down to Los Angeles in the early evening of June 16th, in a state of stunned dullness. The unrelenting stretch of I-5 matches our mood mile for mile through the Central Valley. All of a sudden, on an unremarkable rim, a fox trotting along in the haze of almost evening.

The next day, we go to 356 Mission to visit Lutz Bacher’s show The Magic Mountain. It’s back, razor wire-rimmed courtyard, full not of objects, but of James Earl Jones’s remarkable voice, intoning the “begat” litany from the Bible. I had seen the show earlier, written about its perfection, and was now drawn back. An idea of heaven, through art.

Looking up at the sky, we see that what had been pure blue was now marked with a variety of contrails—painterly marks without any hint of planes. This strange phenomenon will continue all weekend, drawing notice from several friends.

*

Naropa swirls amid an embarrassment of talent, eager students, the knives of professional ambition. The amount of history is almost too much to take in; one singular, marathon day includes Pauline Oliveros and Clark Coolidge, she resplendent in a fuchsia sequined cap, procured at the dollar store that day, as she leads us through a meditative sound exercise, he talking for an hour straight about his collaboration with Philip Guston, to whom he was introduced by Bill Berkson. “One more thing I have to thank him for,” he says, his rough voice breaking.

I could have listened all day, but “I’ve been given the hook; I’ll stop talking,” he said, when he was gently reminded he had run over time. “It’s just too present to me, still.”

Being present is no small thing. A famous poet sits front and center at an evening reading, her face lit by the glow of her phone as she updates social media feeds. That image rises to my head later, when I read Kate Sutton’s letter to Bill: “Here I find myself, struggling to keep my eyes on the page, and not venturing to other devices, other windows (the voices and rooms of my generation?).”

The world of the screen, the cliché of everything at our fingertips. Endless diminution of interest, without cessation. As in the physics experiment, you can never actually touch anything.

*

The world of the notebook, on the other hand, is tactile, finite. “This notebook reflects much, but not all, of what we did,” Bill writes in his introductory note to Invisible Oligarchs, while the Japan notebook facsimiles are full of colorful, pasted-in ephemera: tickets, photographs, blossoms, notes. The poet’s studio—entirely a different creature than a diary. Everything almost a poem already.

If I had to describe Bill Berkson to a stranger, I would use this passage from the Russia notebook:

The issue of sensation—in art, anyway—seems primarily tied to appetite—literally, a taste for living ., the desire (and hence, the will) to live. Berthold (sic) Brecht in his journals took up Wordsworth’s promise of a poem’s efficacy “to haunt, to startle, to waylay” and wondered at “a possible criterion….does it enrich the individual’s capacity for experience?”

And this:

Another gist: that poetry shows consciousness how to enjoy itself—its structures, blinks, blanks, turnings, even its occasional dead ends.

The generous knitting together of worlds and ideas. The opposite of boredom. The mind an elegant, restless creature, never still, until it is.