Reprographic Death and Nate Lowman

Mark Flood

November 1, 2016

1.

We ghastly figures from an ancient age,

Remember grim details of

Pre-digital technology.

The tragic expense,

The arrogant gatekeepers,

The inexorable tape hiss...

We made infernal bargains

With men and machines,

To get our lives copied and distributed.

2.

What if an image was tiny, and we wanted it big?

We went to the drug store, or the university library, or stealthily, at our jobs, to use the copier.

Some called it Xeroxing, at the Xerox machine.

The Xerox machine had a button that said Enlarge. Back when dinosaurs roamed Nebraska, that was our command+.

The highest it could go was 144 percent. If our original was one inch and we wanted it to be blown up to 8 inches, that was 800 percent.

We didn’t do the math. We just kept blowing it up. We blew up our originals, then we blew up the blow-ups. That was enlarging.

Intermediate copies piled up on the flat surfaces of the copier, like pigeons on a public monument.

3.

When we blew things up on the Xerox machine, we got cancer.

That’s what we called the disintegration of the image, as you made copies of copies of copies.

Shades of gray turned into harsh black and white. Edges became jagged. Solids became pitted and pocked with ragged holes.

The more we copied copies of copies, the weirder the distortions became.

Xerox cancer derived from some template that had nothing to do with the original image. It metastasized from some photomechanical mutation deep in the Xerox process, some hellish combo of lightbars and powdered ink.

The new lines and shapes that emerged from this process had a feel, a certain look. But they weren't pretty.

They weren’t involved with what people liked. They had nothing to do with us.

I never liked Xerox cancer. I thought it said something disturbing, about limits, and pointless striving, and failed ambition, and staying in your place.

Its texture was the texture of my frustrations.

4.

Long ago, I shared a Brooklyn studio with Jeff Elrod and Nate Lowman.

They were living and working there. I was just a recurring character, a visiting art-sperado, parking paintings in my section and sporadically trying to get art-people to look at them.

I got to know Nate and his art. Nate was an image juggler, one of those artists who pick and choose from the infinite pile of mass-produced commercial imagery. Image jugglers pick and choose, and juggle their selections, and somehow make them into their poetry and their statement.

There were big Xeroxes pinned up in his studio, and scrappy thrift store canvases, and perishable media like bumper stickers. His compositions involved whole walls and seemed unfixed, subject to continuous flux and reshuffle.

The things Nate chose were a fascinating set. I wondered what images would come next into his magic circle.

5.

I was haunted by some blow-ups of Nicole Brown that I saw in Nate’s studio.

Nicole was shockingly dead, shockingly famous, shockingly naked ... Sunning her boobs in some long-gone LA sunbeam.

This was one of the nude pics Nicole’s sister sold to the tabloids, shockingly.

Nicole dominated the main wall of Nate’s studio. There were two giant Xerox blow-ups of her in the center of the wall, pinned one above the other. The upper Nicole was upside down.

Double Nicole was a dark abstract shape angling across the void. Orbited by smaller images and bric-a-brac, she defined the emotional center of Nate's universe of Americana.

I assumed Nicole was to Nate what Marilyn was to Andy, a goddess of fame and death, a tragic muse.

6.

How does one get the mass-produced image into your art? Collage? Silkscreen? Digital printing?

That's always an issue for the image juggler.

Nate was using Xerox blow-ups on a scale I’d never seen in art. Nicole had plenty of Xerox cancer, but Nate didn't seem to mind it.

Nate’s work changed my attitude. I considered the possibility of approaching cancer as meaning. Copies of copies of copies, turning into something dark and hideous ... Sure, that could be a comment on the human condition.

Was the cancer part of Nate’s content? Was it a meaningful visual metaphor? Was reprographic decay meant to express Nicole’s fame, Nicole’s tragedy?

I hoped Nate thought that way.

7.

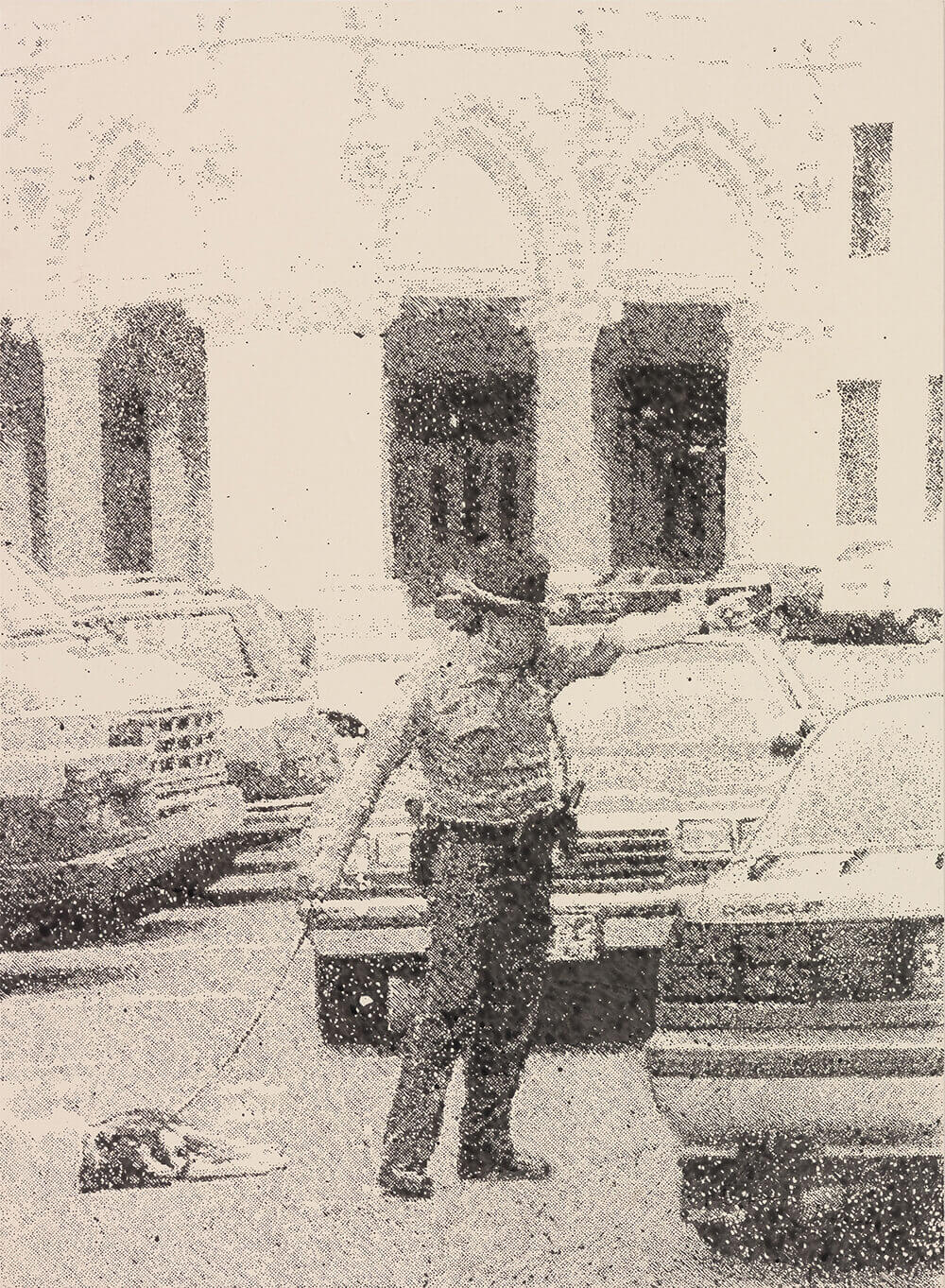

Years later, I visited Nate’s Tribeca studio, where he was creating the series of paintings called Pointers Pointing.

Each painting had begun with a found photo of someone pointing out of the frame. These photos had been copied, and re-copied many times. The images had dissolved into the airy silhouettes of what I called Xerox cancer.

Nate didn’t call it cancer. He called it noise.

Cancer is negative, noise is neutral. Cancer is the fatal proliferation of an evil mutant cell. Noise is mere imperfection in the transmission of information.

Noise may be what people like to call the ghost in the machine. These days, that’s a hope that something of a human spirit, maybe even soul, survives our reckless plunge into the post-human reality of frantic technological evolution.

8.

Nate put the images on transparent acetates, and then projected them onto canvases.

Every detail of the noise was carefully transcribed into paint.

Noise was central to the work, not incidental.

9.

The pointing people in those paintings seem to be gesturing about some secret. Something important, but for us, unknowable.

Art-historical pointing springs to mind, especially Leonardo’s upward-pointing St. John the Baptist. One also thinks of all the contemporary athletes and celebrities who make the same gesture as an expression of Christian gratitude.

But Nate’s martyrs mostly point to the side, not to heaven. They seem more like characters in a secular drama, pointing out where the crime occurred, or which way the bad guys went.

Maybe the drama is about the art itself. The image juggling function is largely a matter of pointing out particular subsets of our endless supply of readymade imagery.

Perhaps these paintings are evocations of the process.

10.

Nate’s cultivation and careful re-presentation of reprographic noise is the sort of technical innovation that elevates painters above the herd.

Important painters have innovative techniques. These innovations may be large or small, obvious or invisible. New techniques makes it possible to make paintings the likes of which have not been made before.

Pollock’s stringy gloss enamel. Warhol’s smudgy silkscreen. Johns’s drippy wax.

De Kooning whipping water into his oil paint with an egg beater, so it never dries, and he can work and rework it forever.

Nate developed reprographic noise as a vehicle of meaning and feeling. Reprographic noise became Nate the Painter’s signature style.

It wasn’t always obvious that Nate, purveyor of mixed media, found objects, and trash-landing, even was a painter.

But it became obvious.

11.

Nate’s Marilyn series involved copying the 1954 Marilyn painting by Willem De Kooning.

The series sets up an interesting triangle of Monroe, De Kooning and Nate.

The classic psychological triangle would involve two men desiring the same woman, and thereby coming into conflict. But we are in the world of images and art here, and things are not so simple.

De Kooning expressed his feelings about Marilyn/women with paint. This mode of gestural abstraction, currently considered a zenith of artistic practice, is desirable yet unattainable. It has receded into a legendary past, becoming untenable as a contemporary operation.

The desire the Marilyn series maps then, would be Nate’s desire to be De Kooning, to be that art hero, to have those relationships with Marilyn, and paint, and art history.

Nate’s Marilyns thrust his signature reprographic noise into the de Kooning/Marilyn matrix. He copied copies of the painting over and over, until it disintegrated into primal reprographic bits, a scattering of spiky atoms and goopy threads.

Marilyn, barely readable to begin with, is much the worse for wear. Nate tried to revive her with some splotches of color that haphazardly mimic De Kooning’s color scheme.

Given the presence of a woman, Nate’s process has to suggest anger, violence, sexual pathology. Yet all that seems as remote as a grainy transmission from another planet.

The real struggle seems to be about stylistic domination. De Kooning’s signature abstract-expressionist mark-making, the quintessential American art-hero paint-handling process, has been effaced and replaced by Nate’s signature mark-making, reprographic death.

The son kills the father, and becomes the king.

12.

As I studied Nate’s noise paintings, I wondered how the noise came to be significant for him.

I look at his birthday and wondered, Did he experience this reprographic decay for himself? Or did he notice it in some ‘80s or ‘90s cultural artifact, and then fetishize it, for its underground coolness?

So I asked him, and he said he’d experienced it for himself. He said he was slow to accept the digital technology.

He knew all about copiers.

13.

He was slow to accept the digital.

Nate was an analog artist, making analog art for a digital world.

His decay was analog decay, and his Americana was analog Americana.

His image search wasn't focused online. He shopped at truck stops, and clipped pictures out of tabloids and art catalogs.

His truck stop, with its sickly-sweet air fresheners, and its racks of bullet-hole decals and bumper-stickers, seemed to be the last analog truck stop, before all the whores and glory holes went online.

14.

Joseph Cornell is one of Nate’s ancestors. Cornell was another image juggler who ransacked disappearing traditions for his art.

Nate had his truck stop. Cornell had Victorian culture, the cabinets of curiosities, the shelves of knickknacks, the scrapbooks, the mechanical toys, the board games.

Cornell was the first to sip at the intoxicating fountain of reprography. Using the photostat process, predecessor to the Xerox, he arranged his rows of identical Medici princes.

He pioneered pictorial repetition as a conveyance of emotional obsession, and he passed that on, to his son Andy.

Andy is widely assumed to be Nate's dad.

15.

Many similarities confirm the aesthetic DNA linking Cornell and Nate. I want to mention one.

Cornell never harvested reprographic noise as expression. An unnoticed participant in Ab Ex, he got his noise from cracked paint, carefully created by baking his art in his mom's oven.

He cracked the paint on his signature boxes, to artificially age them.

Nate’s copy of a copy of a copy is analogous to Cornell’s cracks. Nate presents image decay where Cornell presents paint decay. Both processes suffuse the art with mysterious patterns not made by human hands.

This artificial aging may be about repealing time’s inexorable law. Maybe if new things can be made old, old things can be made young. Then we never have to die.

Maybe it’s about the special fascination ancient objects hold.

Maybe it’s about jumpstarting magical moments of reverie, when time seems to stop.

16.

The image juggler works with time, and what time does to images.

Shocking images have a brief shelf life. Shocking now becomes unshockable yesterday. The fearful horror of the present becomes the familiar, I survived that.

The image juggler’s selection and transformation of certain images races alongside that process.

We can see it in this painting of a picture of a twenty-dollar bill.

The twenty has been folded in a certain way, that makes its design transform into an image of the burning twin towers of 9/11.

I don’t know what drifter created this magic trick, or why. But I know a painter who thought it was worthwhile to copy a copy of a copy of that image, and shove it into art immortality.

9/11, the big violent crazy of our time/yesterday, was always receding. Nate captured it disappearing into folk culture.

17.

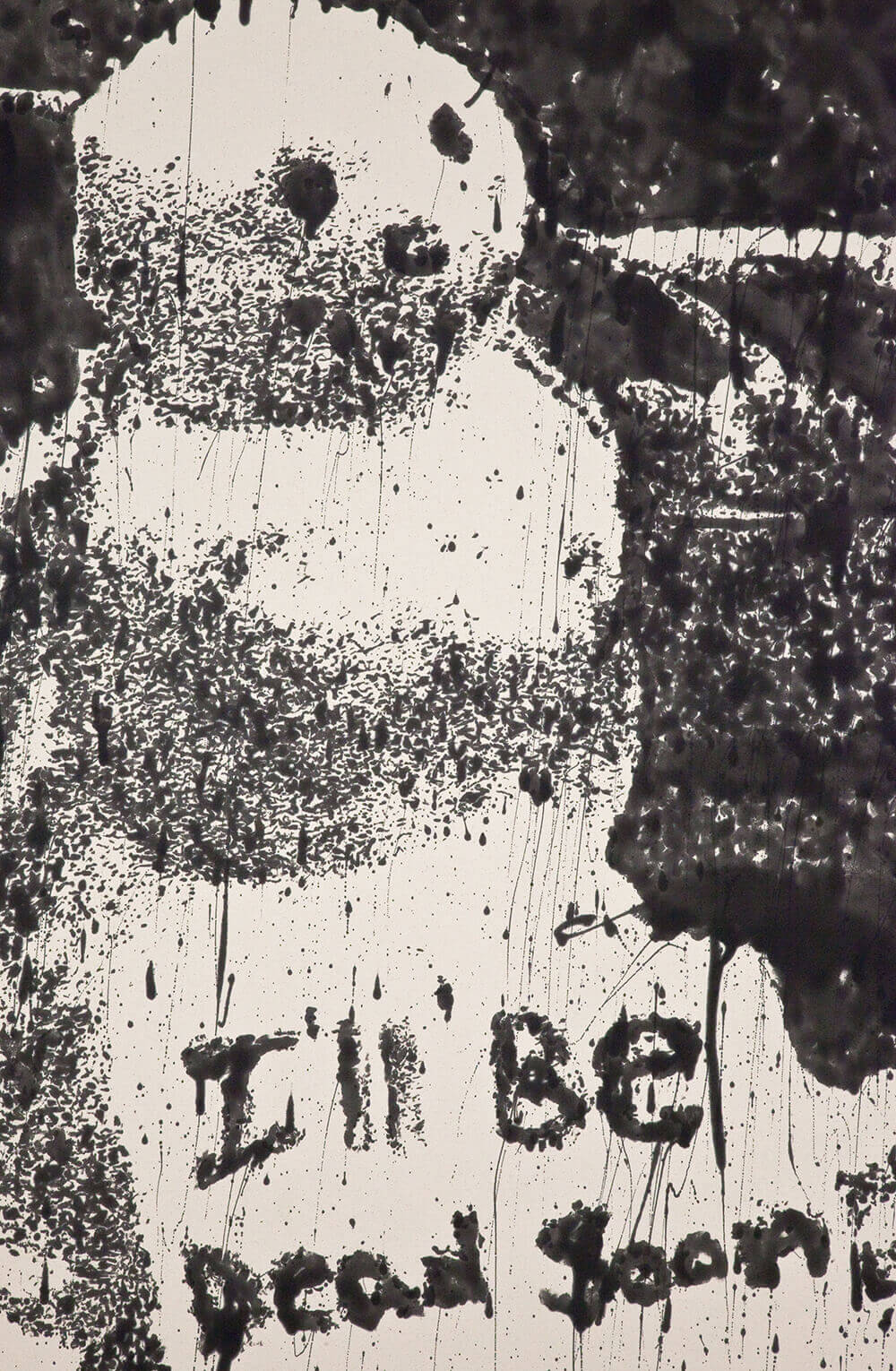

Nate’s art neutralizes violence with gallows humor. It mocks death. It makes smiley faces.

Here’s a Snowman, cracking wise. I’ll be dead soon.

Nate’s reprographic decay makes the joke deeper and darker.

Art will be dead soon. Nate will be dead soon.

18.

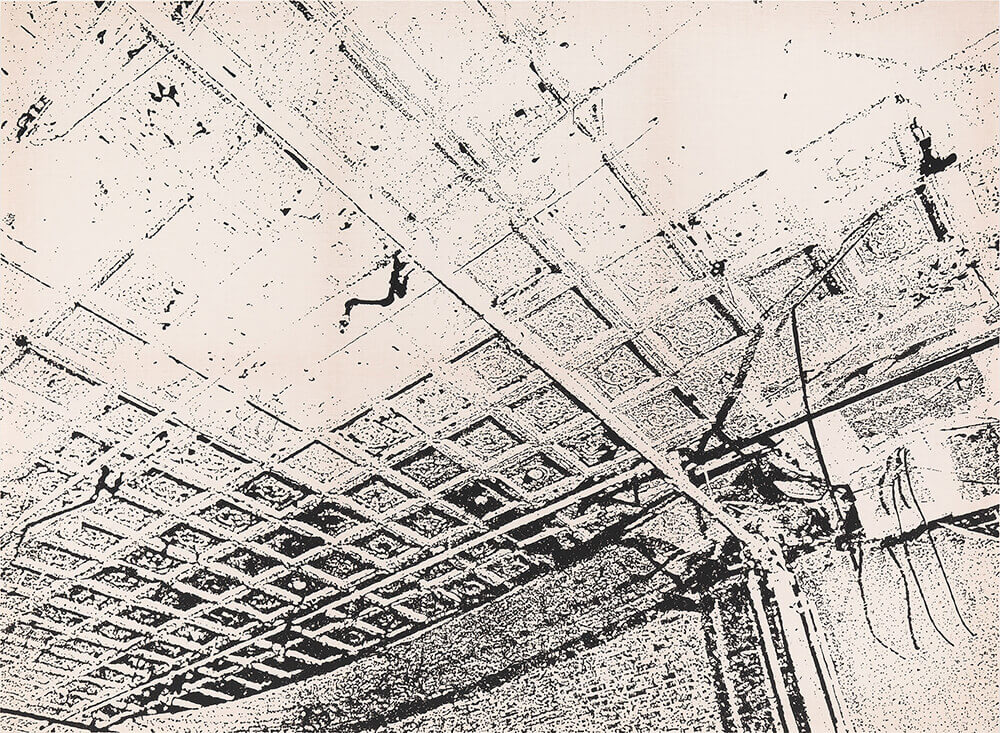

Nate made a series from photographs of ceilings. These were random, boring shots of vintage tin ceilings, cornices, sprinkler-system piping ...

These ceiling images are more intelligible than the contours in Warhol’s Shadows series, but they evoke similar feelings. The careful articulation of the illegible, and the careful articulation of the seemingly random and meaningless, are related aesthetic strategies.

Ceilings are what we see when we tilt our heads back, away from the boredom or horror of life, as it appears at our desks, on our plate.

We tilt our head back as we push away the mundane, the meal, the homework, the tax forms. If there was no ceiling, we would be looking at the stars or blue sky.

We lean back and yawn. We forget about everything as we turn inward and begin a subconscious survey of our physical being.

We stare into space, in the direction at which all those Nate people were pointing.

19.

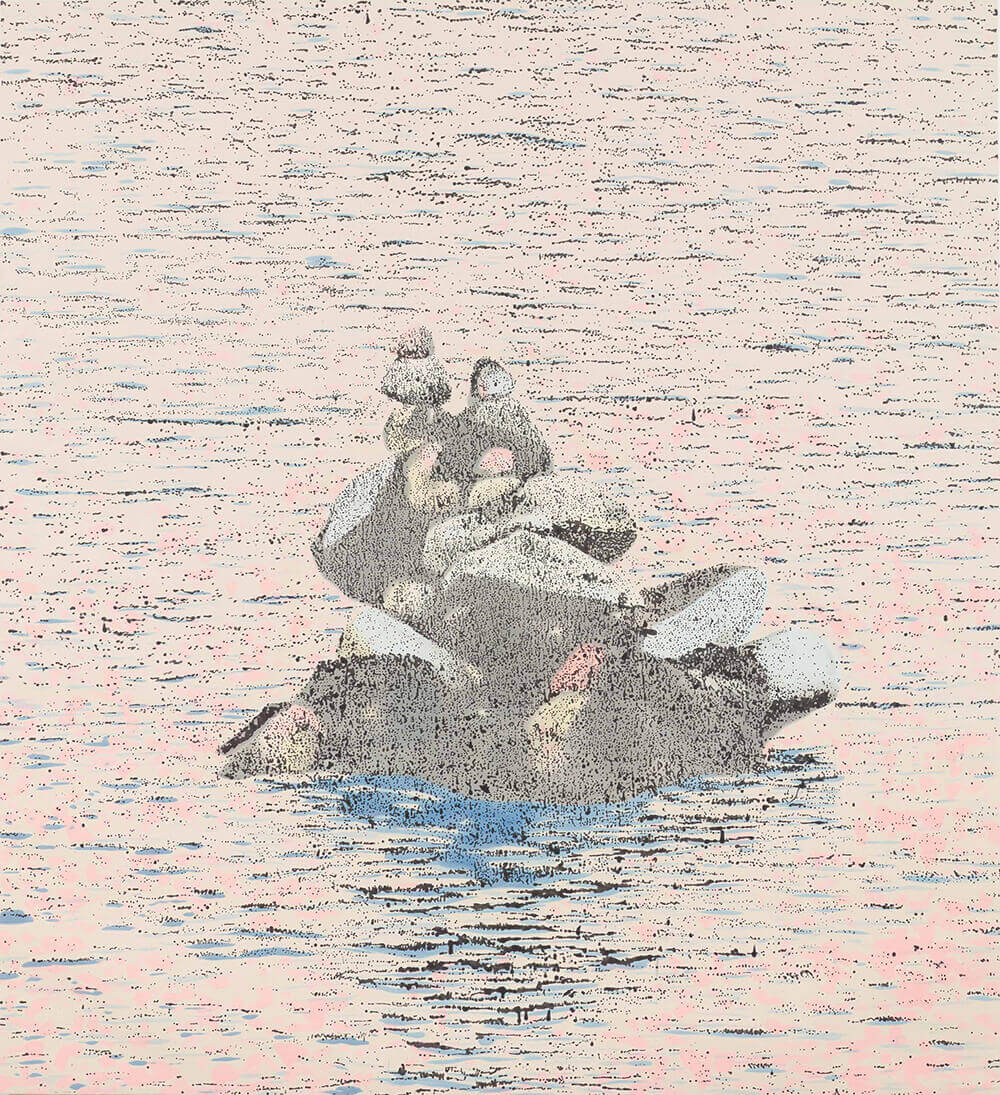

Nate’s painting of a pile of rocks poking out of a lake is yet another metaphysical image, materializing out of a mist of reprographic noise.

Piles of stones go as far back in human culture as we can see. That makes this pile an evocative choice, a choice that says culture, and human, and mark making as a human enterprise.

Piles of stones are also ambiguous. They mark, and they mean something, but they’ve meant many things to many different groups. So this pile seems to mark just mark-making itself, familiar Nate territory.

The noise is so slight and ambivalent that only the careful underpainting allows us to guess what we're looking at.

Surprisingly, the surface of the lake tilting away from us is convincingly suggested by the diminishing scale of these feeble dots. It's an effect reminiscent of the way Monet conveys the surface of the pond in his waterlily paintings.

I wonder if Nate isn’t challenging Impressionist mark-making the same way he challenged De Kooning’s Ab-Ex gestures.

There’s a Wordsworthian reverie in this slight image of a pile of rocks in a lake. There’s a suggestion of twittering summer insects and the sound of lapping lake water, and pink and blue light at sunset twinkling on the ripples.

As usual, Nate conjures plenty out of so much nothing.