Garden of Extinct Flowers

Jacob Dreyer

March 26, 2018

“Heirs to a civilization that is thousands of years old and rich in untold economic possibilities, we stand ready to continue in the total recovery of our personalities.” - Pan-African Cultural Manifesto, 1969

We languidly watched the watery movement of time; now, we see a wave on the horizon. During the several hundred years that Europeans dominated the other peoples of the world, we also dominated the water, the forests, the terrain of the world. The interlocking set of problems we call climate change is the ultimate intersectionality, touching each and every one of us, but in unique ways alluding to our own subject position—artist, surfer, criminal. We conceive of climate change in terms of heat and waves. In Cape Town, on the other hand, the water is running out.

What’s called climate change is not only one change, really, but a web of changes which will ultimately exacerbate the already existing disparities in access to resources. Many of the dwellers of illegal townships outside of Cape Town have struggled with water shortages for their entire lives; what we call catastrophe is simply the normalization of conditions that many are forced to take for granted.

Following the collapse of Apartheid, South Africa successfully managed the impossible: in 1994’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, the nation united for a full recounting of the crimes involved in Apartheid, without any punishments or blame, just closure. Since then, as arguably has taken place in the United States as well, de facto economic segregation has preserved the structures of political segregation, suggesting that it might not be possible to simply move on without substantially dismantling the structures of oppression. These structures aren’t always angry men with guns. Sometimes they are dry faucets.

This February, my brother and I travelled to Cape Town, where our father spent some of his formative years, to find the 1959 pamphlet he wrote opposing racial categories. I went to see a place once warped by racism, a country which in 1994 held the most ambitious reckoning with colonial and racist histories of anywhere on the planet. I wanted to investigate with my family history; the Germans have a word for coming to terms with the past, Vergangenheitsbewältigung, although we don’t. Perhaps they have been forced to do, and we haven’t.

While there, I discovered that Cape Town, in addition to being the most “European” city in Africa, is also the site of a new museum which aspires to define African contemporary art—perhaps even African contemporary life—in such post-colonial light. But what do the peoples, places and things called African have in common? And can a curator honestly confront historical traumas in an empowering way, while also creating a social space for citizens of a world changing before our very eyes?

Ethiopian Airlines

Perhaps the most surprising thing about the direct flight from Shanghai to Addis Ababa was the boredom of the Chinese passengers, their sense that this voyage was absolutely routine. It is without precedent within the 5000 years of recorded Chinese history for ordinary people—not scholars or government officials, but small businesspeople from poor cities—to travel to another continent and build lives there; the people sitting next to me took it for granted, a normal commute. Banal, yes, but perhaps not evil.

The man sitting next to me spoke Mandarin poorly, English not at all, and would probably be looked down upon by Chinese urban middle class types; in fact, he told me that he liked Africa for the freedom that it offered him, managing some factory in a desert. For him, a native of Yangzhou, Addis Ababa was absolutely more accessible, friendly and plausible of a place to live than Shanghai.

Is this man a colonist? Not really. For the Western people observing the Sino-Africans, it seems that a diffuse sense of guilt regarding our historical crimes in Africa manifests itself in the assumption that whatever the Chinese people are doing will inevitably result in the same mistakes, not to say the same fusion cuisines, charming waterfronts of colonial cities, literary and aesthetic hybrids. When a human being decides to treat other humans as if they were objects, that human herself becomes an object, depersonalized. When an entire culture does so—well, you get the drift. Do the new factory towns built by people like the man sitting next to me offer new possibilities for human life, or just a retread of already clichéd forms?

Several hundred years ago, my ancestors, emigrants from a frozen village in northern Europe, moved to Africa in search of—what, exactly? An undefined possibility; a possibility of freedom; a possibility which has coagulated into the form of contemporary South Africa. As I traveled through South Africa (not exactly a homeland, although my relatives lived there for hundreds of years) I did my best to understand what our culture is, and has been; between the time that my family emigrated from Europe and the time that my father emigrated back there, Europeans remade the whole world, a world which mingled certain ideas of equality and freedom with brutal realities of violence and hierarchy; this tension has caused many people, myself included, pain and uncertainty as to the nature of their identity.

In hindsight, we can see the edifice of our heritage not as a single totality, but as a diversity of responses to inequality, some smug, some mournful, some unclassifiable. The Chinese man I chatted with on the flight had what seemed to be an incredibly sanguine attitude. What do you think about Africa, I asked? Food’s bad, but the beef is cheaper than in China, said my seatmate. How long have you been there, I asked? Ten years. I left the airplane with so much more baggage—perceptions, accumulated ideas from god knows where—than that guy who actually lived there. He walked through customs smiling, then lit a cigarette.

Kaapstad

After a brief layover in Addis Ababa, we continued on to Cape Town. To my resigned surprise, it was the week of an art fair; like fashion week, in our fast-forwarded epoch, these art weeks form months, then years. A gallerist I’d been introduced to invited me to dinner at the Shortmarket Club, a local upscale restaurant (the kind that pretends it isn’t fancy but really is, with waiters whose three-day stubble is manicured). I ended up a bit drunk, talking nonsense about China with a woman introduced to me as the Peggy Guggenheim of Lagos.

Reality shimmered back and forth between the pleasures of the chic restaurant and the knowledge, which kept creeping into our conversation, of the deprivation and ecological crises facing the city’s residents. When the waiter mentioned that the food was locally sourced, I was curious. How does one source locally in a place with a severe drought? Since I’ve returned to Shanghai, land reform has been proposed, and the Australian minister of Home Affairs has suggested all white South Africans emigrate immediately as refugees. But they don’t have enough water in Australia either.

My companions went out dancing, I went home; as my taxi glided along the highway in the hills, the driver, who seemed high, told me about the township he lived in, pointing vaguely into the distance. On his dashboard was a book called The Bible of Making Money.

A few months earlier, The Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa had opened on the V&A Waterfront; the owner and the curator both white. Problematic, people said. Jochen Zeitz, a German former CEO of Puma and friend of Richard Branson, had decided to give his entire collection to the museum, before a family reason—I was told in a conversation that was prefaced by “off the record”—made him change his mind. In a small scene like Cape Town, it’s inevitable that people would be snarky about a big new project; I got the sense that half of the people I spoke to had been paid to consult in some way or another, and the other half felt bitter at being excluded.

The Zeitz MOCAA’s exhibitions oscillated between triumphalism about African identities and the unavoidable realities of colonialism and slavery that had formed those realities; Jody Paulsen’s flashy word collages or Athi Patra-Ruga’s work, filled with balloons and zebras, felt like psychedelic pop celebrations, while Godfried Donkor’s work was heavy with the grim weight of slavery. According to its mission statement, that Zeitz “collects, preserves, researches, and exhibits twenty-first century art from Africa and its Diaspora;” but this doesn’t really say much about whether Africa as a place or as a heritage is being privileged, nor about the reality that many in the African diaspora were forcibly removed from the continent, and likely have different concerns than those who remain.

As I strolled past Kehinde Wiley’s painting of the Ghanaian soccer player John Mensah, my thoughts turned to US Former President Obama, of whom Wiley recently unveiled an official portrait. Like Obama, the Zeitz cuts both ways: on the one hand, a cultural signifier of the choice to value African art on the same level as European art; on the other, an attempt to force diverse experiences into any cultural form is bound to constrict and alienate those it supposedly represents. Wiley’s painting was foregrounded, pure portrait, with an abstract background. Other artists seemed unable to forget the background, historical, ecological, and otherwise, that framed the work.

The museum’s idea of African art includes the diaspora, although the historical experiences of African-Americans are quite different from those of, say, Zimbabweans; as with the tension that surrounded Obama, who was accused of not being black enough by some and of being a foreign and illegitimate person by others, the museum didn’t quite seem to be able to decide what it wanted to be.

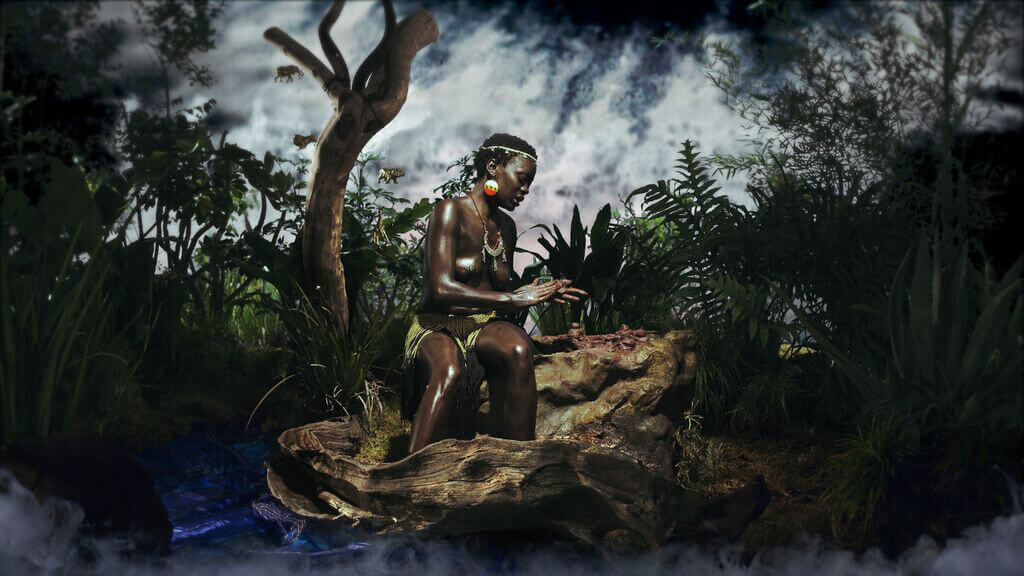

What was for me the most compelling piece, a video installation by Zimbabwean Kudzanai Chiurai, “Creation,” (2012) resisted an explicit read, but came from a very different place than the works of the African-American painters, or those from the diaspora in the UK. The video was set in a shaded forest; bodies moved around, some wounded, others dancing, wordlessly. Human bodies, moving through spaces, some built and human spaces, others natural and mythological forests, displaying wounds and working through them. As a foreigner, Chiurai’s work helped me to understand what could be called “African.”

What made this art African? What sort of experiences qualify: an experience of geography (which would include all persons, regardless of ethnicity) or one of ethnicity (loosely defined, and in any case a bit absurd given the ethnic diversity of the continent)? The art on display seemed to skirt these issues, and we all agreed that the bizarre lobby was the most arresting part of British designer/architect Thomas Heatherwick’s $38-million museum. With a boutique hotel called the Silo next door, which has sent me targeted advertisements on Facebook ever since, Heatherwick’s building is a monument to the human spirit, but mostly the part of the human spirit that mansplains and insists on having one more drink at 3AM.

Zeitz is in the middle of a perfect storm; dependent on the largesse of a billionaire whose requirements of the museum kept changing, needing to attract guests via feel-good spectacle while also meditating historical legacies that don’t really feel good, next to a luxury hotel which hangs ersatz wooden masks on the walls of its gift shop (as I discovered when I unsuccessfully tried to have a coffee there).

Privilege is nice, or it seems that way; but it may be the case that ourselves, our worldviews, are subtly mutilated by the hypocrisy needed to sustain our casual acceptance of it; we wait for our espresso while angrily flicking through our telephones. It’s good if we can acknowledge what our parents do wrong. Can we acknowledge what we ourselves are doing wrong, and more importantly, stop doing it?

Garden of Extinct Flowers

“A full confession can bring amnesty and immunity from prosecution or civil procedures for the crimes committed. Therein lies the central irony of the Commission. As people give more and more evidence of the things they have done they get closer and closer to amnesty and it gets more and more intolerable that these people should be given amnesty.” - William Kentridge

Heading downtown, my brother and I went to the National Library, and there it was: a pamphlet my father had written as an adolescent, priced at one shilling. He was among the first in South Africa to oppose racial categories as such, insisting on a shared humanity under economic conditions. The ANC government which overthrew Apartheid thirty years later is an explicitly racially organized group. It’s not hard to understand why they would feel that black Africans, having been disadvantage for so long, should now be advantaged.

In 1994, my family members who still resided in South Africa emigrated, fearing the sort of land seizures that took place in Zimbabwe. This never happened, although while I was in South Africa, it seemed that Julius Malema’s Economic Freedom Fighters party might be pushing it through now. The volume of violent crime in South Africa, a civil war by any other name, is an unspoken consequence of a political equality that was never accompanied by the economic equality my uncles so feared.

Driving along the Garden Route on the Western Cape, I was overwhelmed by the beauty of the landscape. Similar to California’s Pacific Coast Highway, the Garden Route hugs the coastline, the ocean on one side, and on the other, the dry, grassy veldt. It’s probably better to have art museums in drab cities like London; if set beside the flowers, waves and light of the Cape, the man-made seems puny and overwrought. Nowhere was this more evident than in the Kirstenbosch Botanical Gardens.

A patch of land once owned by Cecil Rhodes, Kirstenbosch was founded in 1913 by a Cambridge botanist named Henry Pearson. It has always emphasized the preservation of indigenous plants. Here the genteel English tradition of gardening meets the South African Sublime. In the world of botany, the question of what is indigenous—as well as what is going extinct—is just as contentious as it is in contemporary art. But the flowers still bloom.

My cousin had worked there for nearly a decade, and we walked together chatting about our family, until we came across the arrestingly titled “Garden of Extinct Flowers.” I’ve known for as long as I can remember that we’re living through a mass extinction event; but it does feel a bit different, to look at a bed of flowers in purples and reds, with outlandish shapes; knowing that each specimen is the last one that exists on the planet earth. There was a graveyard of signs; these flowers existed until a few years ago, but died for some reason or another.

*

All happy families are the same; all unhappy families are unhappy in their own way. We could say the same about cultures, although maybe in our time of mass travel and migration, language groups would be more accurate. The Chinese language, for example, describes the nation or collective as a family: dajia, renjia, jiayuan (everybody, common people, home garden).

If we don’t discover a language to express the fundamental equality of all humans, then it is fairly clear that large groups of the human race will be abandoned as not worthy of saving, and those who are left will live with cultures deformed by guilt. Isn’t our art world a good place to start inventing a language of universal humanity, one which will be durable enough to survive what’s coming?