Fires Blazing on the Moon

Chelsea Spengemann

January 16, 2017

A strong wind blew into town last November 20, right in time for Steam Screens, a 1979 installation-performance of Stan VanDerBeek films projected onto a Joan Brigham steam environment. It had been configured and staged at Knockdown Center in Queens as part of Microscope Gallery and The Whitney Museum’s Dreamlands: Expanded. To make the steam environment, a chain of black iron pipes was arranged around a gravel courtyard and connected to a mobile steam unit. Four of the pipes were drilled with small, evenly-spaced holes according to specifications provided by Brigham. The pipe connection closest to the steam truck had a large valve that, when opened, slowly filled the courtyard with clouds of warm, white steam until the hissing pipes were no longer visible.

Four 16mm projectors and two digital video projectors placed evenly around the courtyard projected onto the steam. To the steam and projected films were added sound, an audience, and, as we learned that night, gusts of wind. Rain or any other weather would have prohibited the piece from working, but wind added an element of unpredictable movement to the piece. It pushed images into and away from bodies. It made the steam dance.

Brigham and VanDerBeek’s collaborative performances with steam and film were fine-tuned over four different projects from 1975 until 1979. Steam Screens was their last project together, taking place in the Sculpture Garden of the Whitney as one of several experimental cinema works commissioned by then-Curator of Film and Video, John Hanhardt, for his New American Filmmakers series. This recent performance of Steam Screens was initiated by Hanhardt’s successor, Chrissie Iles, as part of her exhibition Dreamlands: Immersive Cinema and Art, 1905-2016.

In keeping with the museum’s tradition of supporting experimental cinema, Iles went beyond the standard museum presentation by organizing an incredible group of thematic film programs and collaborating with Microscope Gallery in Bushwick on additional programming for Dreamlands: Expanded. Steam Screens was the sixth performance in an ambitious series of ten historical and contemporary expanded cinema works produced by Microscope, including presentations by Bradley Eros and Jeanne Liotta, Barbara Hammer, Takahiko Iimura, Ken Jacobs, and Jennifer West, among others.

Most of what inspired and informed the recent performance of Steam Screens, besides the invaluable guidance of Brigham herself, came from a manageable number of papers in various archives: correspondence, drawings, photographs, news clippings, undated lists, unconfirmed plans, unidentifiable participants. Precise, yet unrealized sketches for plywood bases on which film projectors and their projectionists could stand. Instructions for a “wind screen.”

We never expected to uncover exact instructions on how to configure the installation, because VanDerBeek (and apparently Brigham) did not work that way. Although VanDerBeek produced numerous documents in the planning phase of all his projects, most decisions had to be improvised in the moment, in response to the specific needs of a particular environment—a process that defines experimental cinema.

Brigham was introduced to VanDerBeek at MIT by Otto Piene, who was then the Director of the Center for Advanced Visual Studies.1 According to Brigham, VanDerBeek had been experimenting with projecting on mist but his efforts were put on hold when he had difficulty securing the use of fire hydrants. Piene knew Brigham was experimenting with steam, so he paired the artists and invited them to produce a collaborative project for his art and technology symposium, Arttransition.

Titled Fog, Mist and Dreams (this name reportedly neither of their ideas), VanDerBeek and Brigham presented their efforts two nights in a row in a fire lane alley on campus. (The fire department was apparently less concerned about blocking a road than one of their hydrants.) Brigham remembered VanDerBeek using a discarded refrigerator as a projector stand and carrying a large selection of his films in a big trunk. Having never projected onto steam, VanDerBeek was unsure which film would work best, so they experimented with different reels leading up to the hour of the performance. One of the first films he tried on the steam was footage he had made of Merce Cunningham for use in Variations V, a collaborative work first performed in 1965 at Lincoln Center in New York.

Until this point, VanDerBeek had been working most of his career on how to use technology to create and then disperse images. He was also interested in melding the human body/mind with machine/image. Having experienced the experimental, interdisciplinary freedom of Black Mountain College in the 1950s, and having always worked with and among some of the brightest artists and scientists in 1960s America, many of the most recognizable values of that era played a role in VanDerBeek’s persistent vision.

In particular, dance, color, and chance combinations of found image and sound through technology became as prominent in his installations as animation and collage had been in his filmmaking. Hearing Brigham mention that the first imagery VanDerBeek attempted to project into the steam was of Cunningham and other dancers was apropos. A moving image of a moving body, inside of which live moving bodies could interact, was very VanDerBeek, and very late 1960s.

The black-and-white dance footage merging with the steam ultimately did not satisfy Brigham and VanDerBeek, but they found that full-color, computer graphic films worked wonders. Brigham’s pipes were connected to her “own personal steam experimental station” on campus, and she recalled the installation working as “a screen that got blown about by the wind,” which “filled the entire fire lane.” She described the event further:

At first, the audience stood on the curb replicating a conventional mode of looking at film. They watched images projected through the steam from the side. And Stan jumped up and down and practically pushed them into the field of steam. He wanted the people to merge with the images, to merge with the steam, that it was to be all one thing. And they were very hesitant to do that, as you can imagine, live steam, but it turned out not to hurt them at all and pretty soon they grew to really like it and enjoyed the sequencing of these beautiful, beautiful images that Stan had projected. And by the second evening the place was completely mobbed with students and guests and MIT professors and all these people were jumping and dancing around in the steam and the images and in the doing, of course, they themselves became projection surfaces.

My experience of Steam Screens last November will likely remain one of the most moving moments in my life, both physically and psychologically. I stood in the steam and in the films as long as I could. On that gusty, frigid night the steam felt otherworldly, primal. At times the colored, warm steam looked like it was coming from multiple fires—like trashcans blazing on the moon. At times the steam was all you could see or smell or touch. It was all-encompassing, and then suddenly it would dance off, taking the expanding image with it.

The soundtracks for VanDerBeek’s Film Form No. 1 (1970) and Poemfield No. 5 (1967), two of the six films projected, were a sporadic mix of fast sitar music, computer generated siren-like sounds, and VanDerBeek’s voice run through a computer, slowly uttering a poem, “Freefall… Falling… Mankind… While Falling.” At the end of the night there was a moment when only the sitar music could be heard, playing loudly. I wanted to dance, and looked up to see projectionists, having abandoned their projectors to join us in the steam, had already started.2

The view from above, from inside looking out through windows, was also stunning. You could see the images projecting onto other surfaces, beyond the steam. You could also see how high and how wide the white clouds were stretching. Being in the steam was interactive. Being outside and above the steam was observatory. Each perspective was rewarding in its own way. The most surprising was the view directly into the projector, which provided the clearest read of the film image across multiple planes in space. Pip Chodorov, as the young child of filmmaker Stephen Chodorov, experienced the 1979 Steam Screens and recalls VanDerBeek telling viewers to look directly into the projections.3

This type of anecdotal information has proven as relevant as the concrete details we often want, such as which films and which music was playing when, and in what configuration. Our goal was to enable a continuation of an experience shared decades ago. Only in performing the piece could one realize the power of looking into a film projector through those white clouds, of straddling a black iron pipe pumping with steam that was glowing with colored light, of looking around to see other people seeing and feeling something similar.

Presence and a willingness to be in the steam is what will continue to bring this artwork alive. Talking to a reporter in 1981, VanDerBeek shared his hopes for the future of Steam Screens: “I’ve been preoccupied with the fact that movies ought to leave the darkened theatre and get out into the city space. I think steam screens should be a kind of permanent celebration on street corners in the winter. You could put them in a lot of places in the city where it would be comforting and a pleasant visual experience.”4

VanDerBeek was clearly excited by the results of his and Brigham’s Steam Screens performances, since he continued to project onto steam and experiment with new methods for doing so until the end of his life. Later instances in which he used steam included his performances for the Intermedia Festival at the Guggenheim Museum, New York in 1980 and Computer Culture ’81 in Toronto. His 1981 retrospective at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis also included a steam installation.

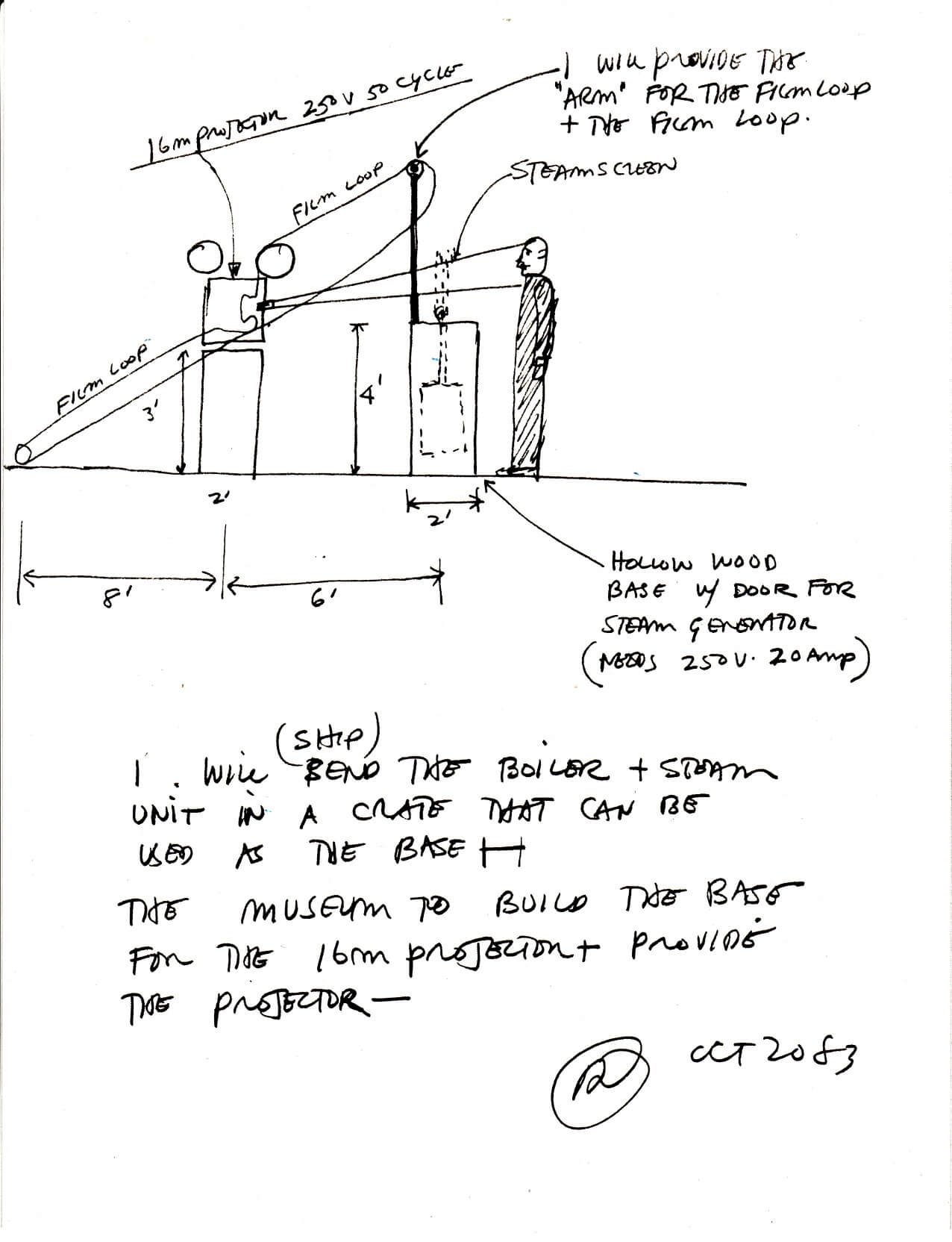

One of the sketches in the archive is for a single steam screen powered by a steam generator enclosed in a hollow wood base. The plan shows a 16mm film projector with an unusually long looper on a pedestal about six feet from the steam screen. A figure is shown standing, facing the projector. Two convergent lines pointing out from the projector lens show where the projection beam lands, and frame the figure’s face. The figure safely stares into the projector, the light from its beam diffused by the steam. As a number of VanDerBeek’s drawings and collages from the early 1950s onward also depict, the human face is a screen.

After the November 20 performance, when the projectors were finally shut down after about two hours, I was struck by the wet pipes sitting firmly on the ground, laid out in their particular line pattern, the empty gravel courtyard turned black with moisture. The backbone of the piece, the pipes, are what you cannot see while the steam and projectors are pumping. The warm, colored clouds—swirling, spinning, jumping, sashaying—hide the pipes from sight, though they are as essential as the projectors, and the films.

The heaviness of these elements was striking after being inside the dematerialized environment they were used to produce. For long moments during the performance, the apparatus required to produce the scene that we had entered became invisible. But, like all the equipment we use to see and transmit information, everyone was aware of its presence. We may be on the brink of conjuring images in the very air we breathe, but there will always be a server, a conduit, lurking in the landscape.

The experimental, open structures of VanDerBeek’s installations, which he sometimes described as templates, were designed to be adapted across locations and over time. It was his hope to create methods for an inclusive, shared experience of the world through images. VanDerBeek always considered the position of the body in relation to images and its potential to break them open for a critical view. He made images move for the ideal of moving people in return.

- VanDerBeek was one of the first Research Fellows at MIT’s Center for Advanced Visual Studies, 1969-1972. Brigham was a Research Fellow from 1974-1982. The information in this paragraph and the following is taken from a talk given by Joan Brigham at MIT on March 17, 2011.

- Bradley Eros, Josh Lewis, Simon Liu, Jonas Lozoraitis, and Rachel Rosheger were the projectionists.

- Email to the author, August 31, 2016.

- Peter Menyasz, “Artist Steamed up Over Warm Dream.” The Vancouver Sun, November 18, 1981.