An Invisible Crown: How to Be an Heiress

Izabella Scott

June 16, 2020

Olga Deterding was so rich that when her red Bentley broke down on the London Road, she left it on the shoulder for anyone to claim. Then she tipped off a gossip columnist, as was her habit, explaining exactly where to find the car, and even suggesting a headline: “Too Rich To Wait.” It was 1963. Olga had become rather famous by the simple fact of being “the richest woman in the world.” Her fortune of £50 million dazzled, and she paraded it like a peacock.

A ruthless self-publicist, she liked to mail out studio shots to columnists and fans alike, which saw her stepping out of Cartier on Old Bond Street, examining a newly purchased jewel in the palm of her white glove. Even the smallest details of her had become the subject of public fascination. “OLGA BUYS A GOLD HONEY POT” roared one paper; “RICHEST WOMAN HATES CHRISTMAS” shrieked another. But Olga was not the richest woman in the world. She was, in fact, a liar.

For the past five years, I have been researching Olga’s life. For two decades, she invented herself through little white lies that got bigger and bigger. She was an unreliable narrator, a self-reporter, setting up camp in a luscious zone between two zoos: journalism and fiction. Over the years, she created her own menagerie, collecting each of her news clippings, cut from tabloids and broadsheets, and lovingly pasted into a set of sketchbooks (perhaps her “life’s work”). Olga often claimed that she was writing a story, a memoir, “the whole truth about my life!”—but she never quite did. Journalists became her surrogate writers; she got them to write the memoir she never could.

With Olga as a muse, I have become devoted to studying female fakers, storytellers, and frauds—self-fabulists who marble together fact and invention, sometimes for dramatic effect, but also, more perilously, for economic gain. Olga’s fortune was mere reputation, but she had enough money to look rich, live rich. She was a fabulist, yes, but she never quite tipped over into crime.

Others have. What follows is a story of a number of women who invented fortunes. They lied, faked pictures, forged documents, and posed as socialites, or royals. They enacted, without knowing one other, The Heiress Con: inventing a fortune in order to create one. And they became stinking rich, for a spell of time, borrowing on the back of marvelous lies. In believing themselves so blindly, so impetuously, they seem to slip outside of normativity. These women lived their fictions, and they were punished.

*

Violet Charlesworth made her money gambling a stolen fortune on the stock market. She grew up in Stafford, a town in the West Midlands, where her father worked as a mechanic. On a trip to nearby Derby, a city of silk mills, Violet Charlesworth launched herself as Miss Violet Gordon. It was 1905 and she was 21 years old. To a shopkeeper in the city, Violet explained that she was the goddaughter of the famed war hero General Charles George Gordon. Almost to her surprise, she managed to elicit a number of silk dresses on credit, including a cherry-red motor cloak, designed to be worn in open-top luxury cars. She made the trip to Derby more often.

After several afternoon teas with a patriotic widow, the story solidified: on her 25th birthday, Miss Gordon would inherit £100,000 from the general, who, after amassing a great fortune, had died rather grandly during the 1888 siege of Khartoum. Violet spoke with confidence, holding her teacup with a pinch. By the end, she convinced the widow to lend the dear general’s goddaughter her entire savings.

A month later, she wrote to a London stockbroker, saying she would like to speculate in a small way, signed her letter Violet Gordon, and sent the firm a sizable wad of cash. Her daring speculation surprised the brokers, who later explained, to a criminal court, that they had been struck by the remarkable business acumen Violet displayed. She liked to bet against the market, in what is known as bear investing, speculating on short-term decline. (One broker remembered “her courage of repeated bear transactions, when scarcely a man beyond the circle of professional speculation would venture upon bear selling!”)

At first she made considerable money. When the brokers finally met her for high tea at the Inns of Court hotel, they were startled to see such a young client. “We were expecting to see a middle-aged woman of the world, but found a country girl, dressed in the best taste, with a charming manner, who told us she had a fortune coming when she turned 25.” With her proceeds, Violet bought herself an expensive Belgian car and glitzy jewels, including a diamond tiara, which she began to wear on motor trips.

“Act as if!” wrote Jordan Belfort in his memoir, The Wolf of Wall Street (2007). “Act as if you’re a wealthy man, rich already, and then you’ll surely become rich.” Violet was a kind of early Exchange Alley wolf. The richer she looked, the easier it was to borrow. Next came a string of St. Bernards, several fiancés, and an impressive mansion in Wiltshire. She also rented an estate in Scotland and attended a spate of Highland balls in her glittering tiara and a grape-green gown, now passing as Princess Violet Gordon. On her sojourns in London, she lived out of the best hotels in Bloomsbury and Holborn, where she was known as a liberal tipper, making daily shopping trips to Hatton Row and attending business meetings around Bank. “Her eyes were of a curious reddish tinge,” another broker remembered, “She could talk in a marvelous way, talk anyone around to her view.”

In a surviving photograph, Violet purports to stand before one of her stately homes, sheathed in a double-breasted overcoat with fur cuffs. A mink stole clutches her neck, and her head flaunts a busy peach-basket hat. Below it, her face looks extraordinarily hard and white.

1907 ruined her. In the financial panic of that year, known as the Knickerbocker Crisis, the New York stock exchange fell by 50% in a matter of days. Violet lost heavily, but, as if following the advice of Jordan Belford, she continued to bet, borrow and bluff, relying more heavily than ever on the story of her imaginary godfather. “I’ll pay you as soon as I get my inheritance!” she would pledge.

Over the next two years, Violet racked up debts of £2 million in today’s terms. As rumors spread from creditor to creditor of unpaid checks, the ring of fire began to close. Finally, on January 3rd, 1909, one day after her alleged fortune was supposed to activate, Violet staged a fatal car crash off a wild coastal road in North Wales. The next morning, her bottle-green Minerva was discovered, its windshield smashed, hanging off the cliff. There was no body; only her Tam o’ Shanter hat, a pocket map, and a suede diary found in the nearby grass. When unhappy creditors came forward, the police turned suspicious. A country-wide manhunt ensued, making Violet a media sensation—the “Girl Swindler.” Eventually she was found hiding out on a Scottish island. “Was she a very clever girl, clever as to telling a story?” asked the prosecution during her trial. Her latest fiancé, from whom she had borrowed no less than £25,000, nodded, still rubbing his eyes.

Violet was not the first woman to pose as an heiress. Take the account of Mary Carleton, an English woman who impersonated a German heiress in the 1660s. She would check into expensive hotels in London, stuck over with fake jewels, and claiming to be a high-born lady—fooling onlookers with letters she sent to herself, which seemed to arrive from abroad. Nor was Violet the last to deploy the heiress scam. Her story finds echo in that of a trust fund con artist of modern times, who like Violet borrowed against the hourglass: an inheritance that would arrive on her 26th birthday. For three years, she conned the New York art world into believing she was a German of silver-spoon lineage. She went by the name of Anna Delvey.

*

In 2015, somewhere between Paris and New York, Anna Sorokin became Anna Delvey. Growing up in the suburbs of Moscow, Anna’s father was a truck driver, while her mother worked in a convenience store. Ten years later, while living the high life in New York on borrowed money, she would describe to friends a decadent childhood in Cologne, city of opera and perfume. By then, Anna Sorokin was mixing in elite Manhattan circles and living full-time as Anna Delvey. In her stories, her father was a German antiques dealer, sometimes oil executive, sometimes diplomat. Anna was heir to a massive trust fund of $67 million, coming her way, on her 26th birthday—which gave her until 2017 to make it real.

An internship at the Paris fashion magazine Purple would provide Anna with the ideal training ground: a crash course in the who’s who of influencers, financiers, editors, and artists. She was learning, mirroring, and if Anna had a special power, it was a memory for names and places, an ability to absorb a lot of information and retain it like a sponge. By a twist of fate, in Russian sorokin means magpie. By the time she arrived in New York in the summer of 2015, where she worked briefly out of the magazine’s Manhattan office, she was exploiting the association and the spritz of European glamour, delectable as any champagne citron pressé.

For the next two years, with intermittent trips out of the US to renew her tourist visa, Anna lived out of hotels, taking selfies. She ran up credit card bills and her Instagram following grew. Out at restaurants and clubs, she mostly managed to dodge the check; she was flippant about money, in a way that only very rich people are, making true Balzac’s maxim: to become rich, first seem rich. It was all improvisation, nerve, as she conjured money with surprisingly simple tricks, like writing checks to herself between different bank accounts, and withdrawing $70,000 of nonexistent funds at a time, before the lenders communicated. Or, when checking into a hotel where she would stay for a month, managing to avoid the basic rule of leaving a credit card behind the desk, which allowed her to delay payment for weeks, and sometimes to walk out the door avoiding it entirely.

When her scams were later exposed—by which time she had stolen over $200,000 in cash and services—she became a subject of fascination, humor, and even admiration. The sheer audacity of it—walking out of restaurants without paying; ordering rounds of drinks only to discover she had nothing but her hotel key on her, and asking friends to pick up the check; perpetually promising to pay later. Her scams were oddly relatable, even achievable. There was something easy-reach about her dream, a teenage fantasy. As a teenager, Anna had obsessed over the film Mean Girls (2004). She also idolized that irreverent New World princess Paris Hilton, who in the early 2000s was just becoming New York’s leading “It” girl, forever seen climbing out of a pink Bentley in champagne-colored tutus, a tiara perched in her blonde curls.

In her glossy pink bestseller, Confessions of an Heiress (2004), which Anna must have read, Hilton provides a how-to guide to acquiring lineage. “In so many ways, being an heiress is in your head,” she writes. “If you follow your own plans and dreams and you don’t let anyone talk you out of them, then you’ll start to get the hang of being an heiress.” The great-granddaughter of the Hilton hotel empire perceives that it’s a confidence game governed by fantasy and self-belief. “People need to believe your life is better than theirs. Put yourself on your own pedestal, and then everyone else will, too,” she writes. “Always act like you’re on camera, and the spotlight’s on you…. Always act like you’re wearing an invisible crown.”

To enter this royalty, Anna set up meetings with tech bros, the sons of real-estate tycoons, star hoteliers, and lawyers like Joel Cohen, famous for having prosecuted the Wall Street wolf Jordan Belfort. Many of them found her unconvincing, eccentric, and ultimately harmless; the people she really impressed where those a little lower down the social rung: hotel staff—who she was known to liberally tip, slipping crisp $100 notes in return for favors—photo editors and content producers, looking for a bit of glamour, friendship, a free ride, or even a leg up in New York’s financially punishing landscape. For this audience, Anna would stage money shots in hotel restaurants and lobbies, appearing with wreathes of designer shopping bags, unboxing new iPhones, sporting the latest Gucci sandals, or decadent gym wear from Net-a-Porter.

It was nothing short of a show. Rule number one of being an heiress, according to Paris: “Choose your chromosomes wisely… If you do have the misfortune of being born into the wrong family, remember: no one has to know. You can always reinvent yourself and your lineage, if you have to. Lineage can be a state of mind.”

One impressed audience member was Rachel DeLoache Williams, an employee in her mid-twenties at Vanity Fair, who had grown up in Tennessee. It was the summer of 2016, and Anna was living at the boutique 11 Howard, eating most nights in the hotel’s Parisian restaurant Le Coucou. There drinking cocktails, Rachel remembers, with a little awe, the heiress’s “ambiguously accented voice” and pre-Raphaelite looks, “a cherubic face with oversized blue eyes and pouty lips.” Over the following months, Anna would scam her out of $62,000.

Did Anna know she was employing a trick perfected by con artists of centuries past, and particularly by Europeans arriving in New York, who played on the fantasy of old world wealth and heritage, to scam ordinary members of the public—other dreamers? One hundred and fifty years before Anna, the Prussian-born scammer Bertha Heyman arrived in New York. Over the next two decades, she would become known as “The Confidence Queen” by the police as she conned innumerable acquaintances out of thousands of dollars. The gambit? Pretending to be vastly wealthy European, unable to access her fortune. Bertha, like Anna after her, was an astute storyteller, drawing on a romantic idea old Europe—as popularized in gothic fiction—a patchwork of forgotten kingdoms and lost princelings, with a lucky dip of inheritances, from vast fortunes to ancestral curses.

Bertha had also perfected the art of ostentatious display. Like Anna, she stayed in the best hotels, skipping bills and exploiting the transformative magic of costume and set. Both women hypnotized friends with small distracting details: the Prussian heiress known for her large gold watches and impressive silk handkerchiefs, the German socialite for her boutique key cards and Balenciaga tote.

Glamer is an old Scots word, dating back to the 1700s, for enchantment, illusion. Its heir, glamour, like a dress conjured by a fairy godmother, is a quality that lasts for a spell of time, then fades. Anna’s time was running out. On January 23rd, 2017, her 26th birthday, she would have no excuses left for the banks and friends, who were expecting her trust fund to kick in. Anna required a wealth-creation scheme, a new dazzling promise to keep collectors at bay. She needed to own the club, host the ball. The idea of a foundation emerged, upon which the whole identity of the German heiress began to hang.

The Anna Delvey Foundation was an imagined arts establishment that would occupy a large building in Manhattan. Anna saw it all very clearly: there would be two restaurants, a German bakery, a juice bar, a cocktail lounge, an artist studio, and a gallery. She found a building with a Renaissance facade on Park Avenue South. It would cost around $20 million to lease. She drew up plans, and devised exhibitions, and her list of partners and advisors grew. According to Anna, Damien Hirst, Christo, Jeff Koons, and Tracey Emin would all exhibit their works at the Foundation. (Later, most of those named, including Christo, who Anna claimed had agreed to wrap the building in plastic, as he had the Reichstag in 1995, would claim to have never heard of Anna Delvey).

The ADF, as it became known, was Anna’s downfall. To make it real, she needed to first borrow a further $20 million. In order to do so, more aliases were born: a balding family lawyer named Peter W. Hennecke who lived outside of Cologne; and Bettina Wagner, a family accountant in her forties, who looked after Anna’s enormous trust fund. Her fake accountants sent asset statements to potential lenders, showing funds of €60 million in a Swiss bank account, which Anna made using Microsoft Word. The scheme fell apart at the last hurdle, when brokers tried to set up a meeting with Peter W. Hennecke, and she was forced to pull out. In the fall of 2017, she was arrested for a string of unpaid hotel bills, and later sentenced to 4-12 years in jail for multiple counts of grand theft and larceny.

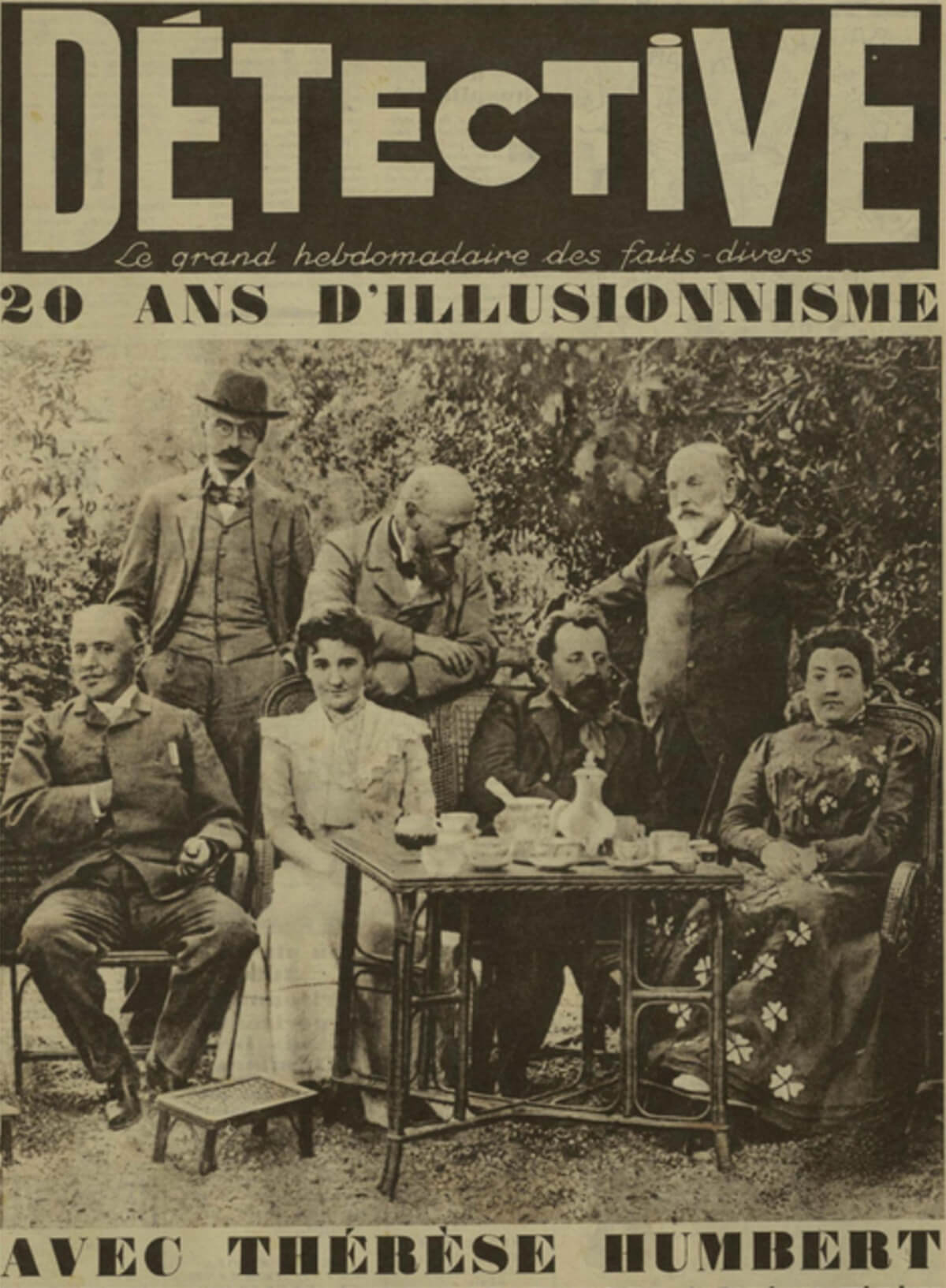

Real fortunes have been made on fictional assets, so why did Anna fail? The difficulty was, she was a one-man show, playing every character herself. She needed an accomplice, somebody to play Peter or Bettina. If she were to have made her foundation real, she needed a family, a clan—like the most famous female scammer of all time, another fake heiress, the talk of Paris, always on the brink of inheriting Fr. 100 million: Thérèse Humbert.

*

Thérèse grew up in poverty, in a village outside Toulouse. Her father was a foundling, a baby abandoned in a church tower and brought up by a priest, and her mother was the illegitimate daughter of a local loan shark. Thérèse had spent her childhood lying. She was adept at winning over the minds of her siblings with stories of castles, lost wills, betrayals and benefactors—stories inspired, in part, by her father, who in his thirties had been adopted by a widow, a woman who claimed him as her son and gave him her name, Daurignac.

As a teenager in the 1860s, Thérèse managed to elicit free clothes from a Toulouse shopkeeper, preempting Violet, with stories of a breathtaking ancestral home that had been left to her by an old spinster. With time, Thérèse managed to make her castles real—the equivalent of Anna getting that $20 million loan. Indeed, the village girl lived at the center of Parisian society for over 20 years, running on debt but wielding real power. Why did the spell last so long? It comes down to the intricate story she told about her inheritance—a story that was so engaging, so thrilling as it unfolded, that it left the beau monde agog.

She needed an accomplice, and he came in the form Gustave Humbert, a law professor who married her aunt. Gustave’s star rose throughout the 1870s, until he was appointed the Minister of Justice, a top-level position in the Third Republic. Though considered by all a truly upright man, he had a crooked alter ego. In the early 1880s, he helped to shut down an upstart bank, the Union générale, and was handsomely paid off by the Rothschilds, some Fr. 2 million. That was when he remembered the rumors he’d heard of his young niece Thérèse and her imaginary castles, the talk of Toulouse. Just as Thérèse was spinning stories of her ancestral home, and trying to flip her fictions into a real fortune, Uncle Gustave was looking for a place to hide his illicit cash. They were the perfect pair: Thérèse had to conjure a fortune, Gustave had to hide one. Thus began the Humbert family scam.

The Humberts: Gustave, Thérèse, Frédéric, Emile, Alice, Romain, and Maria. They would become characters in a living play, a reality show directed by Thérèse. First there were was a quick, Shakespearian double wedding, as the Daurignac children married their Humbert cousins (Thérèse and her brother Emile married Gustave’s children, Frédéric and Alice); Thérèse's remaining siblings, Romain and Maria, were folded into the family, taking the surname Humbert. The new clan then spent a month together, refining the details of the story. Thérèse would be, as she had so often claimed, heir to her imaginary estate. Forged deeds attesting as much were kept in her bodice forevermore.

The story went like this: an American millionaire named Robert Henry Crawford had been taken sick while travelling through the south of France, falling through the glass window of a lingerie shop in Toulouse—and into the arms of Thérèse’s mother. Years later, so the story went, Thérèse would discover that Robert Henry Crawford—possibly her true father—had written a will on his deathbed leaving his entire fortune to Thérèse. The amount, Fr. 100 million, was astounding. “A hundred million!” noted a friend. “People took off their hats to a sum like that as they would have done before the Pyramid of Cheops, and their admiration prevented them from seeing straight.”

Land agents and speculative financiers soon came flocking. With creditors almost begging Thérèse to take out loans, the Humberts embarked on a lavish lifestyle. Thérèse bought an impressive property in Paris just off the Champs-Élysées, and then set about throwing parties in the billiard room or around the grand staircase, and appearing across town in her carriage. She became famous for her high-piled coral hats, adored peacock feathers, and enormous jewels, including a necklace made up of pearls from the Imperial crown. On Saturday evenings, her opera box was crammed. Bankers, lawyers, diplomats, bishops, and dauphins attended her parties; the guests appeared in the next day’s papers. She was an influencer, an “It” girl, known across Paris for her inexhaustible purchasing habits, accompanied by the unshakeable refrain “Je veux, J’aurai,” I want, I shall have.

At the center of the house, kept in a locked chamber on the third floor, was a large strongbox. In it, explained Thérèse, was Robert Henry Crawford’s fabled Fr. 100 million in bearer bonds; creditors were only allowed to glimpse it.

The brilliance of Thérèse’s story hung on its ongoing elaboration. It now emerged that Robert Henry Crawford had written two deathbed wills. In the second, he divided his fortune between Thérèse and his two sons, rather lazily called Robert and Henry. A lawsuit followed. The masterstroke of the disputed wills was that it meant Thérèse was unable to actually lay her hands on her wealth, explaining her eternal need for credit.

All members of the family had their part to play, as Thérèse weaved a web of sympathies and rivalries as complex as any novel. The Humbert family story unfolded publicly, played out in artful balls and dinners held in the grand living room, and dissected in columns the following day. All of Paris tuned in, the gossip columnists racing to keep up. As a real life family drama in installments, unfolding week by week, it was the reality television of it day. In Keeping Up with the Humberts, a rapt public watched the exploits of a family who are rich and famous for being rich and famous, engrossed by a string of proposals, affairs, breaks-ups and make-ups.

La Grande Thérèse, as she became known, might be the family’s Kris Kardashian, the “momager” who pitched the idea of the show in 2006, and managing her five daughters’ careers, taking a cut of their earnings in the meantime. (She remains the show’s executive producer). Like the Humbert’s before them, the Kardashian-Jenners seemed to conjure vast fortunes out of thin airtime. The net worth of the daughters alone is astonishing: Kylie Jenner is the world’s youngest billionaire; Kendall Jenner is the highest paid model in the world; Kim Kardashian has made over $100 million in a decade. Incidentally, Kim first came to public attention as Paris Hilton’s stylist, making her, like Anna Delvey, the intern turned heiress.

The Parisian public of the 1880s binge-watched the Humbert family show. So rapt were viewers, that Thérèse’s inventions began to enter the collective imagination, taking on real forms. Public sightings of the Crawford brothers, cast as shadowy troublemakers, were reported to the papers—Robert, or Henry, seen by one bailiff shirking around the Hôtel du Louvre, or by another eye-witness, ominously knocking at the Humbert’s door. Thérèse was not done with her inventions, and she relied totally on her clan to make them real. It now emerged that the Crawford brothers would waive their claim on the second will, on the condition of marrying a Humbert. Thérèse’s youngest sister Maria was chosen.

Perhaps the winning episode was a famous dinner held at the Paris mansion around 1890. It was billed as the moment when Maria—the family’s Kim—would at last accept the Crawford proposal. It received maximum publicity, and the Humberts did not skimp on the theatre. At a dinner produced for the proposal, an enviable guest list was narrowed down to 25, including a cluster of well-placed journalists. The table was fashioned after a royal wedding banquet, a flow of lobster claws, flutes of iced rum sorbet, and vessels of soufflé. Attendees took their seats to watch the Crawfords arrive—impersonated by Thérèse’s brothers Emile and Romain.

The Humberts gave the performance of their lives. During the first course Henry Crawford, played by Emile, sporting a twirling cane and a pleated cloak, deposited a fine gold wedding ring at Maria’s place—but she brushed it aside. As pudding was served (beveled glass dishes of wild strawberries and ginger cream), Henry tried to place the band on Maria’s finger. Her eyes stung with opal tears, and she pushed his hand away, before rushing from the room in her duchesse gown, dropping a ballroom slipper on the stairs. Thérèse rose from her seat, in a raven-feathered hat, announcing tragically to her guests that the wedding would have to be postponed yet again.

The family began to fall apart after Gustave’s death in 1894. His position as Minister of Justice had been a seal of approval, making the family beyond doubt. Now rumors began circulating about unhappy creditors unable to elicit repayment. In 1901, following the collapse of a bank, a secret creditors’ meeting took place in the north of France, resulting in a spate of lawsuits. A simple legal request pulled the rug out from under the scammers: a court judge asked for the permanent address for the Crawford brothers. Over 20 years, the courts had been asked to litigate the wills, but never to verify if the Crawfords actually existed. When the address Thérèse provided on Broadway proved false, the strongbox was ordered to be opened. The Humberts were nowhere to be found, and a locksmith was summoned to break open the padlock. Lawyers, creditors, journalists, and the Humbert’s loyal but clueless henchmen gathered round. To the shock of every onlooker, there were no bearer bonds, no wills to be found. Inside: an old newspaper and a single trouser button.

*

Some people write fictions; others live them.

In 1907, the whole of Britain was gripped by the Violet Charlesworth affair. She had transgressed the line between invention and deception, and would be sentenced to five years’ hard labor on multiple counts of fraud. But the question remains: at what point does a liar believe her own lie so much, live it so much, that it becomes true? To the Daily Mail reporter who finally discovered her, Violet gave a smiling explanation of the accident—the smashed windscreen, a blow to the head, followed by an uncontrollable urge to flee—never slipping out of character. Indeed, Violet kept self-identifying as Miss Gordon in the months after her arrest. Hired to appear in music halls around London, she would walk on stage, simply as herself.

Thérèse seemed to never leave the stage, even as the final curtain went down. During her public trial, she refused to break the fourth wall as she gave her last great defense. In an ecstasy of invention, Thérèse spun a final tale: the cosmic fortune had been left not by the Crawfords after all, but by one of France’s most notorious enemies, François Bazaine—a commander sentenced to death in 1888 for surrendering to the Germans. The millions, she now wove, had been Bazaine’s payoff from the Prussians; when she realized it was an enemy bribe, she burnt every last penny in a patriotic fever. After a few moments of stunned silence, the judge responded, “But that does not explain the button, Madame!”

She was sentenced to five years’ solitary confinement, and never seen again.

Thérèse did not just want fame and money. Like Violet, she wanted to become her fiction, to make it real. Could this have been her undoing? The Kardashian-Jenners have not made the same mistake. If they’re scammers, the scam has worked—or at least, it has worked inside a paradigm where celebrity itself is a scam. In a world mediated by TikTok and Instagram, the line between “real” and “fabricated” has blurred; identity formation is bound together with small acts of editing, exaggeration, lying—from filters to Facetune to fake photos. We’re all at it, but in this habitual sleight of hand, the Kardashians are among the masters. (The fact that Kylie Jenner has been inflating the success of her cosmetics company for years, and in fact is not the world’s youngest billionaire, as recently exposed by Forbes, hardly seems to matter.) They racketeer a cold, diamond-hard perfection that exists best in the realm of images. They seem to understand this, know they are idols revered for flawlessness, icons rewarded for being images before anything else. (Paris Hilton understands this too, constructing herself as living image: “The way I keep people wondering about me is to smile all the time and say as little as possible,” she writes in her manual. “I’m a fantasy to a lot of people.”)

A hybrid of heiress and influencer, Anna based herself on Paris and Kim—spoilt, reckless, and always looking good. Even as her scams fell apart, she was unwilling to exit an heiress state of mind. In the summer of 2017, as The Beekman and W New York hotels pressed charges for skipped bills and a court appearance was scheduled for September, Anna did what the Cologne heiress-influencer Anna Delvey would do, and not the exposed lawbreaker Anna Sorokin: she flew west and checked herself into Passages Malibu, the celebrity rehab center operating out of a $15 million beachfront mansion. She explained to staff that her father was refusing to release her $67 million trust fund until she did some work on herself. Anna spent two months in an off-the-grid lap of luxury, swimming and clean-eating, as if recovering from an heiress binge. That October she was arrested in a sting coordinated by her friend Rachel. The trial took place 18 months later.

Anna the scammer has since become far more famous and influential than Anna the heiress. She has managed, in part, to joyride the story of her crimes. For her court appearances in 2019, she hired a celebrity stylist, Anastasia Nicole Walker, to dress for the trial; the “court looks” appeared on a new Instagram feed. From Rikers Island, where Anna will remain until at least 2023, she claims to be writing two books: one about her life before confinement, and one after. “I guess I’m fortunate enough to go to real prison,” she told one journalist, “so I’ll have more material”—a bravado which smacks, to me, not of authority or defiance but the false confidence of a poker player with a dead hand.

While she sits in jail, the story has been taken out of Anna’s hands—mediated by friends, observers, producers. In 2018, Netflix optioned the rights for the story of the “wannabe socialite,” as told by Jessica Pressler in The Cut. In 2019, HBO followed suit, snapping up another version of the story told by Rachel in her memoir My Friend Anna (2019). Here I am, too, transfixed by these three scammers—by their true lies and crimes. Thérèse, Violet, and Anna: I find their deceptions thrilling; if you’ve got this far, you probably do too.

Why? In some sense, we are all fake heiresses, self-inventors ruled by the ego-trick—that deception that makes each one of us feel like a coherent person, a self. Do we all feel scammed already—because capitalism is a scam? Because the very idea of inheriting something feels like scam—a game of chance, a kind of cheat? Wealth, after all, is a greasy pole, and the slippery nature of affluence has always provoked anxiety among the higher classes: part dependent on chromosomes, and part self-made, nouveau. So what divides the wannabes from the legitimate, the fakers from the real? Perhaps the whole flimsy concept of the “fake” inheritor is a fantasy that the rich need because it makes them seem authentic.

Or does it have something to do with the fact these scammers are heiresses rather than heirs, women who conjured money to acquire influence—a soft power historically never available to women. There has always been a special kind of hatred reserved for women, out of class, who have made themselves rich: upstarts, wannabes, hacking the social code. Once in a while someone like Violet or Thérèse or Anna comes along. They defy the law, take it too far and risk exposing the whole sham—the underhandedness of inheritance, of chromosomes and gender, the downright unfairness of birth—and so they must be defamed, locked away, eclipsed by mythology, and turned back into just a story.