It will still all happen

Claudia La Rocco

August 13, 2018

I can hardly read the notes I took the night I watched Variations on Themes from Lost and Found: Scenes from a Life and other works by John Bernd. It was this spring. I’d taken the train to Stanford University for the performance, a muscular and episodic reimagining of several of Bernd’s works from the 1980s by the New York choreographers Ishmael Houston-Jones and Miguel Gutierrez. I had seen a recording of the show made during its premiere two years before at Danspace Project, part of the multi-week platform Lost & Found: Dance, New York, HIV/AIDS, Then and Now. But video isn’t the thing. It doesn’t tell you what it feels like to sit in a dark theater next to the San Francisco artists Rhodessa Jones and Keith Hennessy, to hear Rhodessa’s quiet mm-hmmms and watch Keith watching so intently, one hand tucked under his chin, fingers pressed into cheek. To sit just behind members of Bernd’s family. To feel the bass hit your sternum when the score gets going. To hear the dancers’ breath grow heavy when they get going.

All the little internal moves dancers make—like the physical version of someone muttering to themselves. How beautiful. Private. Preparatory. Utterly perfect.

That’s something I wrote. As well as “& where is the meeting of heaven & earth, it is the horizon, which we shall never reach.” I have marked it as a quote, but when I reach out to Nick Hallett, who arranged and remixed the score, he tells me those lines don’t exist. Not in the work. Where did they come from?1

John Bernd was a galvanizing figure in New York’s downtown dance scene. He was also one of the first people in that community to contract HIV/AIDS, when it was still known as GRID. He died in 1988, after seven years of living with this virus, sometimes incorporating into his art his efforts to understand and deal with what was happening to him. He was 35 years old.

There are so many stories like this. So many lives reduced to a cliché of AIDS literature: important artist dies young. It goes without saying, and therefore should not go without saying, that those who are not artists, those who are not white, not male, have not even been granted this cliché.

*

But then, a cliché is manageable. Keith Hennessy moved to San Francisco from Canada in 1982. He was in his early twenties, and the AIDS epidemic was beginning its rapid, deadly advance. He talks about the anecdotes he’s grown used to repeating when asked about those years. Tell them enough times, they become their own version of the truth. As he said in a pre-performance panel discussion at Stanford with Ishmael, Miguel, and Rhodessa: “What did I actually live, what are the stories that we’re telling, and then what is the recorded history… How do these things not get confused together in my emotional body or even intellectual body?”

*

The first time I saw Keith Hennessy dance, I think, was in 2009, when he shared a bill with Melanie Maar at what was then Dance Theater Workshop and is now New York Live Arts. (Bernd was an associate director of what was then Performance Space 122 and is now Performance Space New York; this mania for verbal land grabs. Out with the old.) He performed his solo Crotch (all the Joseph Beuys references in the world cannot heal the pain, confusion, regret, cruelty, betrayal or trauma ... ). I remember being overwhelmed, impressed—beyond that I have only scattered, imagistic fragments. Crowding around him in the lobby as he gave a prelude of a talk that was also a poem; crowding around him again at the end, on stage, as he painstakingly threaded a needle through his skin and the clothes of three audience members. I reviewed the show for The New York Times, calling it “an outré, charged solo.” Who was I back then? I have only scattered, imagistic fragments.

*

I was moderating the panel at Stanford because the year before, as editor in chief of Open Space, I had organized Lost and Found: Bay Area Edition—a series of commissioned texts, conversations, and performances inspired by the original Danspace Project Lost and Found. Rhodessa and Keith had been part of the culminating event at CounterPulse. Rhodessa talked about the Medea Project, which she founded in the late 1980s to help incarcerated women give voice to their experiences and has since expanded to include women with HIV/AIDS. Keith gave a performance lecture, attempting to address his personal experiences as an artist and an activist—and also, as he took pains to emphasize, just (just!) a person who did not die.

*

Crotch is now ten years old, and Keith recently performed it again, at The Lab in San Francisco. Looking at promotional materials online I saw “an outré, charged solo” used as a pull quote. These are not words I would use now, not outré anyway. There’s nothing shocking or excessive about it (two words the internet posits as synonyms), though it does deal in excess: channeling Beuys and a history of largely white, largely male continental philosophy, at one point Keith attempts in seven minutes to chart a line from Plato to Hegel to Judith Butler, scrawling it all out in markers on a plastic sheet attached to wooden boards held up via a makeshift rope system by three audience members. The tension between “I’m in charge” and “we’re all in this together” runs throughout his work. Also the attempt to swallow the world in an effort to say something meaningful, something vulnerable. Anger and grief and generosity all knotted up in one virtuosic, messy skein.

These past two and a half years, I’ve seen several of Keith’s performances, including site-specific one offs and works in progress. It’s been one of the pleasures of my voluntary midlife uprooting from New York to San Francisco: to see the stuff that doesn’t travel, to see where the stuff that does travel travels from. It’s not always easy to keep track of those lines of influence and lineage—though maybe that is one of art’s great pleasures in the end, and why art history survey books tend to be so unbearable. Everything neatly packaged.

In 2004, I was an NEA Arts Journalism fellow at the American Dance Festival in Durham, North Carolina. A newly minted dance critic, I had just discovered Miguel Gutierrez, the immediacy of his raw, powerfully intimate voice. If I remember right, Miguel had come to visit the fellows; I’m sure at any rate I was talking about him as if he sprang Venus-like from the waves. Another fellow, a gentleman not based in New York (maybe from the Bay Area?), stated that there would be no Miguel Gutierrez without Keith Hennessy. I didn’t then understand his irritation; the memory is lost, but I’d wager I shut up in a hurry and pretended to know who Keith Hennessy was.

“It will still all happen” is something Keith said this summer at the beginning of Crotch, as we all crowded around him on the sidewalk outside The Lab, where he balanced on a metal utility locker, his head almost disappearing into the undulating foliage of an adjacent tree. It was chilly and a strong wind was blowing, clouds and sun moving overhead: such a typical San Francisco evening. He had just fed us chocolate from a tray and was about to read a poem: pain, sex, loneliness, art. In other words, the world.

*

In 2007 I wrote an article for The Times in an effort to come to grips with all that I didn’t know, hadn’t seen, couldn’t see. I turned to Suzanne Carbonneau, who had been my teacher that hot, lonely summer in Durham:

“I think dance in some ways is for people who don’t love cold, hard facts,” said the dance historian Suzanne Carbonneau. “Something you remember more often is in fact more decayed, more removed or more transformed than something you haven’t thought about in a while. We’re remembering our memories.”

Or, stranger yet, we’re remembering other people’s. You can’t talk about memory in dance without talking about the lack of documentation, which often means that our memories, and the expectations that go with them, aren’t even our own.

Suzanne is the closest I’ve come to having a mentor in criticism. When I knew her, she was quick-witted and sarcastic and generous, possessed of an impressive poker face. She is one of the few people I really regret losing touch with.

I am thinking of the various rituals Keith employs to emphasize the imperative, and impossibility, of togetherness. Sewing himself to strangers, the needle only piercing his scars and their clothing, the connection tenuous, bloodless. Asking everyone during the performance lecture at CounterPulse to take agave into their mouths as a meditation on kissing, the sweet, sticky liquid squirted from a plastic squeeze bottle. Risk and sharing, but only the ghost of risk, the ghost of shared experience.

*

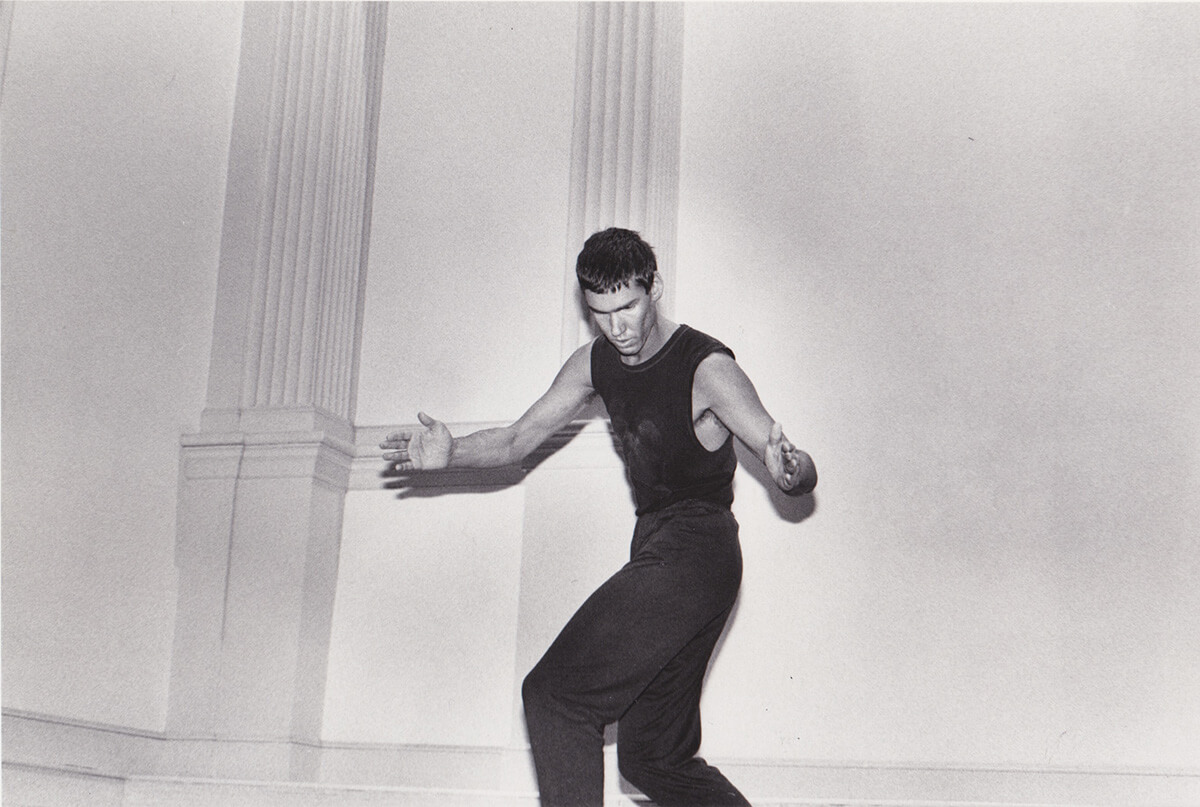

A monitor was set up in the lobby of the Bing Studio at Stanford this spring: on the screen the ghostly images of dances past. You got a sense of Bernd’s movement quality. You witnessed, over a period of several years, as he went from a beautifully buoyant youngster to a terribly thin man; the illness encroaching. I’ve read now multiple times that he snuck out of a hospital room (once? More than once?) in order to perform. History becomes mythology.

Lost & Found: Dance, New York, HIV/AIDS, Then and Now has its genesis in Ishmael’s discovery, years later, of a zine he and his friends made in 1998 to mark the tenth anniversary of Bernd’s death. The writing, republished in the platform’s catalogue, is compelling and painful. You are peering into something private.

When Miguel saw footage of Bernd’s work he knew he had found an ancestor, someone with whom he was in unknowing conversation. A lot of the recent HIV/AIDS discourse in performance has been about that recuperation. In the Bay Area, for example, Brontez Purnell discovering Ed Mock when performing in He Moved Swiftly but Gently Down the Not Too Crowded Street: Ed Mock and Other True Tales in a City that Once Was, a 2013 work by Amara Tabor-Smith, a choreographer from a generation between those two men. Mock was by all accounts a singular figure in experimental performance circles in San Francisco, galvanizing both as a revered teacher and an electrifying performer; he died of AIDS-related complications in 1986. Brontez, like Miguel, moves fluidly between music, dance, and writing—and, like Miguel recognizing himself in Bernd, he saw himself in footage of Mock.

In dance you can’t go to the source. If you’re lucky, you maybe have a fuzzy video. If you’re really lucky, Cynthia Carr’s writing. And you have the people who worked with these people. The game of telephone.

Rhodessa’s father used to say: “everything that’s happened is happening right now.” I have only seen terribly inadequate videos of Ed Mock, but I would like to think that he still walks swiftly but gently down the streets I now walk down. I have, after all, seen the beautiful sureness with which Amara moves. I have seen Brontez’s voluptuous, canny theatricality. I have seen Keith’s shape-shifting improvisations.

Someone in the Stanford audience said that Ed Mock was her John Bernd, launching Rhodessa and Keith to reminisce about this pivotal, artistically restless individual. “He could do anything,” Keith said of Mock’s apparently genre-defying improvisations. “There was no one in the same league … to see me or be influenced by me is also that you’re in a conversation with Ed Mock. But you wouldn’t know it. How do we talk about the dead, how do we talk about the people whose work was not canonized?”

Writing this down now, I remember three other questions he asked in a 2017 performance-lecture at CounterPulse: “What is remembering? What value is forgetting? Why talk about dancers while dancing is still possible?”

*

These days, depending on one’s mood and proximity to the news cycle, any form of artmaking can swing wildly along the crucial-impossible pendulum. Sink, a new solo Keith performed the weekend before he revived Crotch, is laced with that tension: Why make art? We must make art!

Who is the “we” who gets to do this?

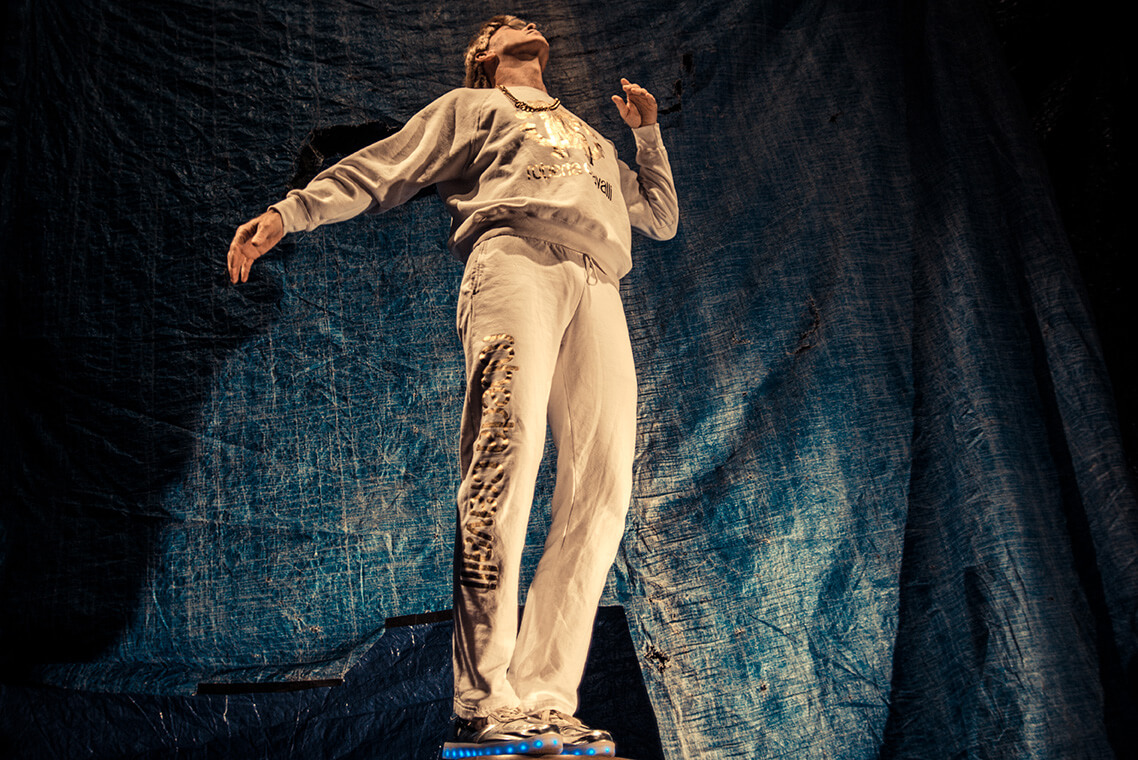

Keith begins Sink in a white track suit. He wears a gold chain, his face slightly oranged except around the eyes, a blonde wig covering his close cropped grey hair: the white male monster to end all monsters. His body undulates in slow motion, energy radiating out from the pelvis. Later he sits hunched in a fur hat and coat, singing a raw song about guns and terrorism. We all sit around him. The song takes its time, at some point morphing into Nirvana’s “Lithium”—in Crotch he ends with “Something in the Way,” his body dusted with glitter, his voice muffled by a set of dentures painted to look both glowing and rotten: songs of rage and grief and impotence. Songs of ruined magic that still might conjure something momentary and swift.

*

For days after seeing Variations on Themes from Lost and Found: Scenes from a Life and other works by John Bernd, I listened to one of the songs in the score on repeat: New Order’s “Age of Consent,” released in 1983. The lyrics are painful, ending with a long repeat of the phrase “I’ve lost you.” Yet the song is intensely alive, buoyant (that word again). When I listen to it I think of the dancers racing up and downstage in the small Stanford studio, punctuating their runs with these space-eating leaps that almost land them in the front row of the audience. And I think of one of Bernd’s simple, evocative drawings: one line bisecting the page, two diagonal lines stretching from the bottom corners into that line, flanking six irregular little rectangles: a road, one long passing lane, reaching into the horizon, where we never shall.

- On the day this essay is published, I finally hear from Ishmael that the lines are Bernd’s. I’m relieved to know this, and struck, again, by how easily in their aftermaths dances are forgotten, confused, misremembered, misreported … Miguel said something during the pre-performance panel at Stanford about how his experience of seeing a work begins long before he actually sees it, when he first hears about it and hears how others are talking about it. It occurs to me, then, that this experience of seeing also lasts long after one has actually seen the work. Ephemerality, in this way, achieves a strange, warped permanence.