Triangles in the Sand

Kevin Killian

November 19, 2018

I had never been to Studio 54, “Studio,” is how Will and my other young boy friends referred to it, but it was then much in the news, and it was another place, like Hawaii, that Arthur didn’t want to go to, in this case because you couldn’t hear the music at Studio, and there were too many celebrities there, people without talent, just bone structure and good drugs.

Instead of Studio he took me way over to the west side, the gayest part of the Village, to the Paradise Garage. If he wasn’t gay how did he even venture onto that block? It was the late ’70s, when the art of cruising had finally been perfected, ditto the whole courtly love apparatus of swooning on the street when a cute trick passed by, or walked relentless in front of one for blocks on Essex Street, his ass a puzzle screaming to be solved, or a moving game like the Tetris of the future, blocks of buttocks to be negotiated and conquered. I would say, “I could eat him up like an ice cream sundae,” and Arthur would pause, say nothing, perhaps tilt his head towards me quizzically, almost as if I had said something unpleasant, or so foreign it was like I was speaking in Bjorn and Benny. What was the matter with him? Next to him I thought I was too gay, a concept that otherwise did not exist in 1978.

Late, late, late, we got there around 2 a.m. It felt like a prom in a way, there was confetti on the floor, but darker than my prom had been. Soon enough I had lost him in the shadows of the club. An hour or so later I was hanging around and a little short older man challenged me about how I’d gotten in. (You had to be a member apparently.) I explained, he was confrontational in this Brooklyn way that made me sigh inside, thinking, “This sure isn’t Studio 54.” Had I been ditched? I should have felt shamed, but I was so drunk I was just mouthing off to this little Danny De Vito guy.

“Is it daylight outside?” I said, holding on to last scraps of dignity. “I’ll leave if it’s daylight.” Presently DDVG lost the energy to 86 my ass, and then Arthur Russell returned, blinking from out of the darkness. Had he been watching this ignominious encounter, I wondered? Mostly we were dancing. It was a mixed club filled with blacks, women, Latin guys, Caribbean girls, a fair amount of disco queens in satin shorts and tiny tops. You could hear the music for real there. There was what seemed to be an hour-long mix of the Jackson 5 version of “Forever Came Today.” Now that I think of it, Arthur was the one who explained what a mix is! You can see I wasn’t very hip.

The club played hundreds of tracks I never knew what they were, but I remember he had a fondness for this one song by Norma Jean (was that her name?) and it was called “Saturday.” He liked Nile Rodgers and Giorgio Moroder and again, it was how bombastic and pretentious Moroder could be and we both liked Four Seasons of Love and Once Upon a Time and wondered what would Moroder do next to top that storied grandeur? At the same time, the music always threatened to turn into just pure sound and maybe that’s what Arthur liked—that possibility laid out open and threatening.

I remember the Bee Gees had a song called “More than a Woman,” and that this intrigued Arthur with the ambiguity of its reference. What would being “more than a woman” entail? Was it in fact a gay coming out number, the Bee Gees acknowledging their gay fans, and giving us a little something? “More than a woman—more than a woman to me.” I think now I was just dumb, and socially challenged, expecting everyone to act like they went to Catholic high school—boy’s school—as I had, and that everyone was from Long Island’s North Shore, since East Egg was the byword for vacuity. I thought I had all social types pegged, but I didn’t know anything about people beyond my purlieu.

And to be fair to myself, he wasn’t all that easy to reach either. It wasn’t that he was alienated from other people, not per se; he seemed to be enormously popular. At a coffee shop we’d be eating and our table would get filled one by one by guys he’d worked with or danced with, and I remember having to introduce myself once because he was too high to remember my name. He looked at me and his mouth moved but if you gave him a hundred dollars he couldn’t summon my name.

One of the fellows sitting two seats away from me was Lance Loud, my gay idol previous to Allen Ginsberg, —Lance Loud of the Mumps, whom I’d adored in the PBS show An American Family when I was 20 or so and frozen, transfixed to public TV. Lance Loud who’d had the balls to leave sunny Santa Barbara, his mom and dad, and pound the bell at the desk at the Chelsea Hotel, checking himself in. Those mean desk clerks at the Chelsea. And while we sat there companionably together, I saw another guy’s hand slipped into the back pocket of Arthur Russell’s jeans and I wondered who this guy was.

Of the two of us I was the more alienated in actuality, awash with envy and aggression, while he, Arthur, was merely alienated from his body, and in an interesting way—that’s how I see it now, having lived in California for 35 years where these aperçus thrive like the avocados. Again and again I kept running into the basic problem, that I was based on Long Island and that consequently I was a dud. Maybe he was screwed up in his libido, but he was an adventurer, living a creative life, while I was cooped up in my rented house in Rocky Point studying Tennyson, Browning, George Eliot. And bringing guys home, but I wasn’t an artist.

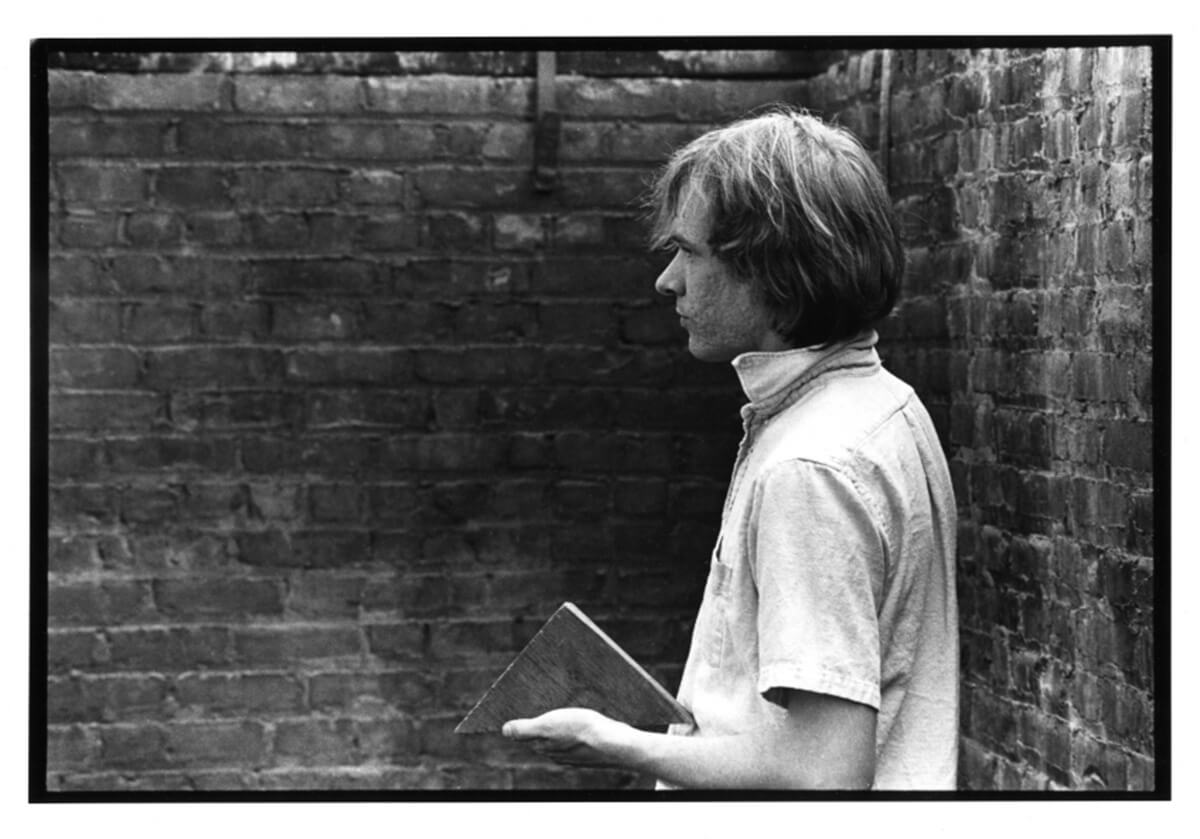

Every time I emerged from the Midtown Tunnel into Manhattan I would find that Arthur Russell had played some fantastic gig the night before, though he didn’t seem to be famous exactly. He wasn’t a good fit for me. He deserved somebody better and I deserved somebody who could peer under my anomie and maybe find out I was sort of cool in an ass-backward way. He has handsome but oh, that complexion . . .

Will said I had the shallow personality of the club kid without the appeal—the drive but no charm.

*

Later, Arthur and I went to the movies and argued about what we should see. Perhaps because he wasn’t in it for some reason, Allen had advised against seeing The Last Waltz, not worth our time he’d told Arthur. One morning we folded the Daily News against a mailbox propped open to the movie listings. We wound up deciding on the original Grease, then a new release. I can’t remember if it was Loews State 1 or 2—whatever the upstairs one was—near Times Square—and moviegoers on line said the management had slotted what might have seemed like a turkey into a small theater, then when it became an unexpected hit there were lines around the block and it became a real challenge to get a ticket.

We tried to see it at noon and couldn’t get tickets till nine or ten at night. In the meantime we sort of had nothing to do, kicked around here and there, looked at the lions at the Public Library, and as the hours wore on I got the impression that Arthur was not enjoying our date much. In hindsight it was a wee bit ludicrous, dragging him to this show. Finally to save the situation I did what I’d done many times before, acted all into him and came on bi-curious.

I asked him who that man was feeling up his ass at the restaurant.

Arthur first didn’t remember.

I stuck my own hand into his back pocket to improve his memory.

He blushed but kept flipping the albums in the import bin. Even chain stores like Sam Goody’s, he always said, sometimes hid treasures. One time, in Berkeley, he had found a case of the Velvet Underground’s first album at a church bazaar sale. This was the record with the Warhol banana pasted on the front, ingeniously pink under its yellow peel, and these babies were mint, still in cellophane wrappers. A case! And they were asking twenty dollars for it. He had to borrow the twenty from a girlfriend but it was worth it, for the proceeds of that find saw him through a whole semester of careful eating and dining—already it was a very rare record at least with the banana unpeeled. In his pocket my thumb and forefinger pinched his butt gently. “Who was the guy?” I repeated.

He said the guy was called Steve and he was a musician.

“So you’re not gay, but him you let into your back pocket and you just keep his hand there like it’s renting a room.”

He shrugged, grinned, a grin that said “bi-curious” right back to me, like looking into a mirror.

I hypnotized him into going back downtown, back to the building where Allen lived, on East 12th Street. Arthur lived in the building too, though not perhaps in this very apartment—(this was murky to me, unsettling, as though I were not wanted in his actual dwelling place, where he lived). This was a Spartan flat with only a few pieces in it, all of them white, cream, sand or putty colored. The floorboards were bare, though an area rug covered the lintel between two rooms. It was hot in that flat, and the window opened only a crack. You could see streaks of pink and yellow across the blue of the sky, and the noise was fierce, it was what excited me about Manhattan, so different from San Francisco where I had spent the previous summer, the summer Elvis died. In San Francisco cars don’t honk their horns. Arthur said it was the quality of the street noise that made different composers write as they did, that John Cage wrote very differently when he worked in San Francisco than he did in New York, and differently in Seattle than in the other cities.

I thought he was projecting, speaking really of himself and the way that he had ridden this trajectory from the prairies of Willa Cather country (or wherever), which must show up in his music somewhere (vague misconceptions of Ives), then he’d gotten blissed out in San Francisco, and now New York was drilling syncopation into his head as it had Lorca and Stravinsky and Piet Mondrian. Like a boy I was always reaching out manually, and for me the direct approach worked, so I had been pawing him all the way from Broadway and Times Square, one palm flat on his crotch, when no one could see, in what I hoped was a masterful or, at any rate, a practiced way.

Inside Arthur’s building, the bright room had a bed but we didn’t lie down on it, in fact we didn’t even get close to it, we just skinned down our pants and stood by the window, jerked each other off by the window, my back bumping against the painted wall. I blew him a little, cranked myself up, unsteady. His face was damp, rosy. In my hands his cock seemed large, sturdier than I would have guessed, like a stick. I asked him if he was ready, he nodded. Asked if he had any lube, he shrugged. That made me think, maybe this wasn’t his place. But that was cool. The whole scene had something to it of the meeting between Brando and Maria Schneider in Bertolucci’s steamy 1972 film Last Tango in Paris; it made it more exciting that it was the flat of someone else. (And later in life I could see occasions where a trick pad, if that’s what this is, could come in handy.) I reached round and bounced his ass in my hand, sluicing his dick. Or maybe when I’d asked about the lube he’d thought I wanted to fuck him, you could tell he wasn’t going there. But he had a great Ryan McGinley style ass that felt luminous and insolent in my hand. At that point I was going to shoot and told him so, aim for the floor he whispered. “You too,” I said. I kept thinking this is all I had wanted from Allen, but Allen had turned away from me, too busy for mere me.

38:8 And Judah said unto Onan, Go in unto thy brother’s wife, and marry her, and raise up seed to thy brother.

38:9 And Onan knew that the seed should not be his; and it came to pass, when he went in unto his brother’s wife, that he spilled [it] on the ground, lest that he should give seed to his brother.

Later an expert on Arthur told me that we were probably in Gregory Corso’s room—who knew? It was so neat and spare. And Corso had that messy aura to him, but this place was perfect for this Amish sex we enjoyed. Squirt.

Squirt.

Figure X.

*

Excerpted from Kevin Killian’s Fascination (edited by Andrew Durbin) available December 11 from Semiotext(e).