Message for Ya!

Ben Ratliff

February 11, 2020

Mark E. Smith, the singer of the English band the Fall—if it was a band—died at age 60 on January 24, 2018. A day later, the British DJ Luke Blair, known as Lukid, played a two-hour mix of Smith’s music on the internet radio station NTS. That’s a hard job if you want to do it well, because a memorial broadcast for a musician who made lots of records would generally seek to contain him, and Smith did much to lead you away from the idea that the Fall could be contained or reduced to an essence.

Likewise this essay, two years later: a hard job. However much I will try to convince myself and you that I’m doing otherwise, it’ll be containment and reduction by another name. But the work feels good.

A few of the Fall’s songs are favored as anthemic by those who paid attention to the group; a couple became radio hits, known in England far beyond those specialist audiences. The first song Lukid played was nothing like a hit, and possibly not essential: a live version of the song “Hard Life in Country,” slow, limping, and queasy, from the 1982 album Fall in a Hole—if it was an album—recorded in Auckland, New Zealand, at a club called Mainstreet Cabaret.

The song’s drum pattern, roughly, is a heart rhythm—boom-BOOM (rest-rest)/boom-BOOM (rest-rest), and so on, mostly played on kick drum alone. The sounds of two strummed guitars, played by Craig Scanlon and Marc Riley, lie over that. One is a gronky, depressed, eighth-note pattern, interestingly out of tune; the other is a clean, high-on-the-neck, full-treble, up-and-down melodic scrubbing, a bit like an alarm, and abjectly related to the joyous rhythm lines Nile Rodgers played in Chic.

Smith often said—surely as a provocation, but what if we took him at his word?—that he was not a musician. Likewise, in a bit of insight that is hard to forget once you read it, the visual artist Nikholis Planck once suggested: “It’s as if Mark is always guesting on vocals.” What could that mean? It could mean that Smith was both at the center of things—the organizer of the group, the voice of it—and also off to the side. The way to find Mark E. Smith is to look off to the side.

“Hard Life in Country” is a hectoring rant, speeding up and slowing down, with wild rhythmic emphasis on certain words, phrases, final syllables. In its sliver of narrative, clichéd attitudes about country life slide into suggestions of violence. The song might be unbearable but for its gothic omen-glint, which never dims. Smith begins after about a minute and a half. He sounds like he’s singing along to it rather than singing in it. “It’s hard to live in the coun-try,” he chants, “…in the present state of things. Your body gets pulled right back; you get a terrible urge to drink.” (Emphasis on the -kah in drink.) A darker turn in the next verse: “At 3 a.m.-muh! / the stick-people re-cede! / the locals get up your nose / and leather soles stick on cobblestones.”

Later Smith mentions a “scandal,” and a local publishing of “your” address. He reasons: “It’s good to live in the country / you can get down to real thin-king / walk around, look at geometric tracery / a hedgehog skirts around your toes / fall down drunk on-the-road.” By the end, things aren’t good at all. “V-v-v-v-v-v-villagers!,” Smith yells, “are surrounding the house-uh! The locals have come for their due!” There is amplifier squeal, presumably when Smith wanders too close to the back line, away from his central position. As you listen, you become aware of physical specs: the range of his movement, the compromised equipment, and the dimensions of the high-ceilinged club, especially when the two drummers that were in the Fall then—Paul Hanley and Karl Burns—smash their cymbals in tandem at the end of four-bar segments.

As far as I can tell—some data about this has been collected, believe me—the group itself never started a live set with that song; it’s all middle, unrelieved badlands, pure bottleneck. Lukid! What an advanced act of subversion on his part, betraying the usual ways music is acknowledged and delivered. By doing this, in a non-obvious way, almost without showing his hand, he seemed to mirror Smith. I think this is because Smith did not “re-invent” the song, the album, the genre, the band; that would be PR talk, and in it lies the implication that only one person can do it. It is more that Smith represented a leaderless effort to de-invent those things. His ongoing challenge, if I hear it right, is to contemplate the ritual and immediacy of music at its uncontainable middle—not just his, but let’s start with his—rather than through structures of musicality/album/song/year/era/genre. The containers come off, the stick-people recede: what are you left with?

Smith liked to work; the Fall made more than 30 albums and many more more EPs and singles. If you add concert recordings, Smith’s spoken-word records, his dance music and sound environments made with Jan St. Werner and Andi Toma of Mouse on Mars, and live radio sessions under the direction of the BBC DJ John Peel, you’ve got more than 100 hours of music. This is an impressive amount, and the muchness is often the first thing acknowledged in any piece of writing about the Fall. The second thing, if it is also critical writing, is to point toward a best era, or a best record. Let’s deal with these problems in order—let’s start with the fact of a record, any record.

If you have ever felt doubt about the authority of the typical ways music is made, apportioned and understood—band, album, song, era, year—the Fall might be a group for you, and Fall in a Hole might be an album for you, or rather a starting place, an unfolding riddle.

*

What was this record? It was, for a decade and a half, basically a bootleg. Not “canon,” not official, not up to professional standards of live sound, not legal. The New Zealand musician Chris Knox, who has since become almost a saintly figure of DIY creativity, believed he had permission from Smith and his partner, Kay Carroll, who was the Fall’s manager, to record it at Mainstreet on August 21, 1982, with his TEAC 4-track open-reel recording machine. He also believed he had permission to give the recording to Flying Nun, the Christchurch-based record label, which was not the Fall’s label at the time and never would be.

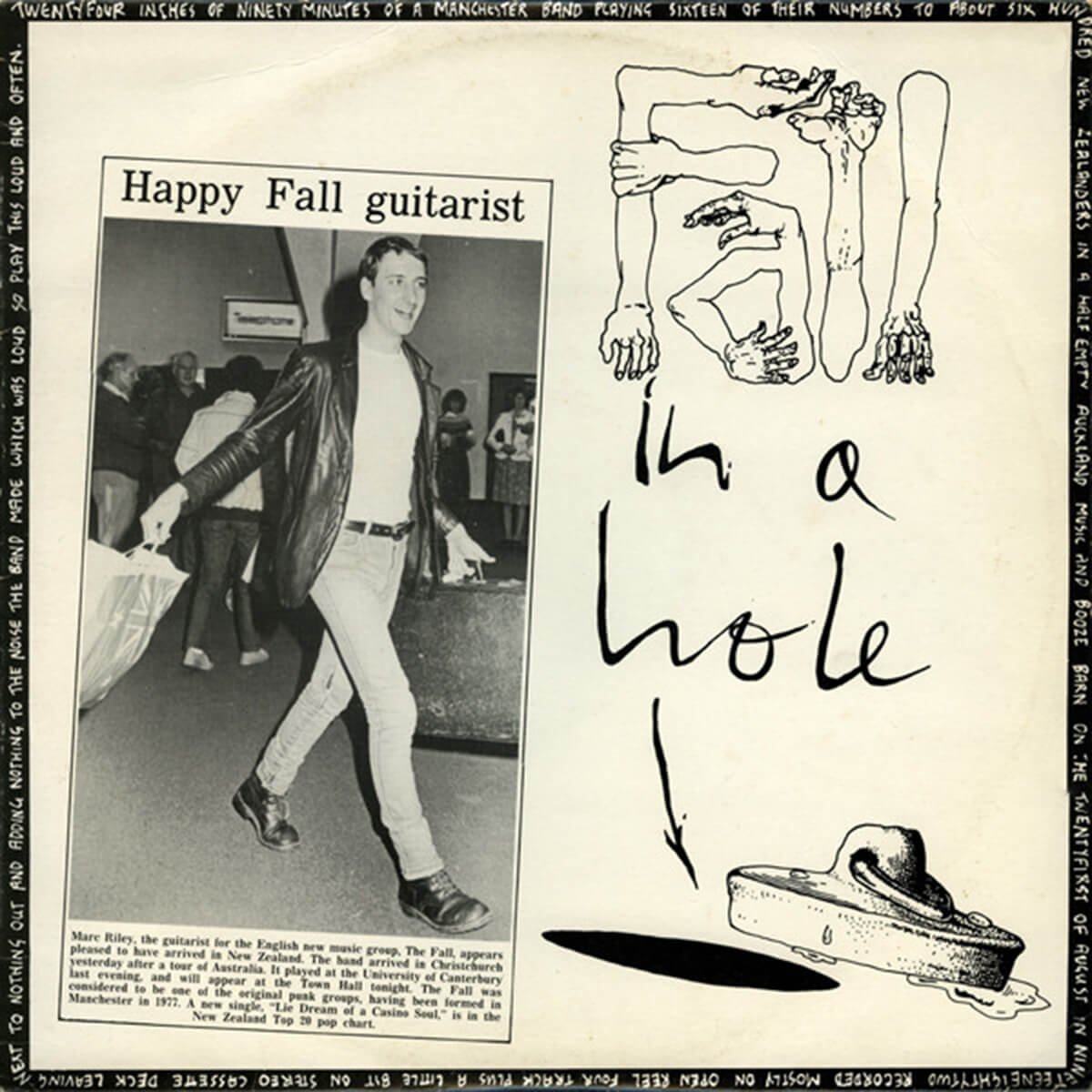

It came out at the end of 1983. Its cover, designed by Knox—who was also a visual artist—looked like a cousin of the last few Fall records: scrambled, hand-written, doodled, vernacular. Its left side had a large reproduction from the Christchurch Press: Marc Riley entering Christchurch airport, under the headline “Happy Fall guitarist.” Riley looks hale. The arrival of an English group with a song in the New Zealand top 20 was exciting enough to warrant an item in the daily paper. By the time Smith discovered a copy of Fall in a Hole for sale in England, he had fired Riley from the band almost a year ago. Therefore the album cover featured neither the front person of the band nor a current member of it. Smith was bothered by Riley, but also had no DIY scene-allegiance. He ordered a cease-and-desist against Flying Nun, demanding money from past sales; apparently the label had not negotiated the rights to export copies outside of New Zealand, nor had they bothered to let Smith hear a test pressing.

By the late 1990s Smith had acquired rights to Fall in a Hole and had it re-released on his own label, Cog Sinister. In his sort-of autobiography, Renegade, told to the writer Austin Collings—a book more removed from the idea of authorship than almost any I have read, as if CCTV microphones happened to catch him being small-minded for a couple of days—Smith implies that he chose the cover in order to ridicule Riley, who, he felt, was “parading himself like a chief swan to all these imaginary fans at the airport.” In the book (if it is a book), Smith seems to want to take credit for Fall in a Hole. My sense is that nobody can.

Fall in a Hole, as an album, is weird all around. It comprises two twelve-inch discs: one, at 33 1/3 RPM, unusually long, containing the Fall’s whole set that night at Mainstreet—nearly 30 minutes on each side, such that it feels strange for a listener not to get up and change it sooner; the other, 45 RPM, much shorter, for the encores. By 2016 the English label Cherry Red had acquired Fall in a Hole from Smith, and released it as a nearly three-hour “expanded edition” on streaming services, including not just that night’s performance but others from that tour and one from 1978—further confusing just what Fall in a Hole is or was.

Its power as a document is not necessarily through the efforts of the Fall, who didn’t plan it, nor through the efforts of Knox, who recorded it at the high end of amateur. The ambient paranoia in some of its songs (“Hard Life in Country,” “Prole Art Threat,” “Backdrop,” “The Man Whose Head Expanded”) affirms the idea that it could be a kind of surveillance recording, produced not by a person but by chance.

Fall in a Hole isn’t “great,” but couldn’t be better. It has, let’s say, magic properties. It conveys the thrilling enormousness of the band’s sound through strain; it clobbers you even as it lets you walk in and look around. It can’t be reduced, which means that nobody will sacralize it. It will always be off to the side.

There are two basic academic ways to understand any music, from which all others flow: how it achieves unity as it moves along, and how it is understood when finished. Both are difficult with this band: wherever the Fall finds any logical or documentable traction, the signals get weak and nothing moves predictably. They had just managed to gather an audience in England by the middle of 1982; by obscure logic, this was why Smith wanted to head for Australia and New Zealand for a month. “I’d had enough of the music scene, all that psychedelic shit and white honky monody,” he said in Renegade.

In Australia their records were not on the charts, but still Smith and Riley were invited on a daytime TV interview show. (In the surviving video clip, Smith has a black eye from where Riley had punched him the night before.) The Australian drummer Jim White saw them play in Melbourne six times across seven days in 1982; he figured there were a few hundred people, on average, at each gig. “One of the greatest weeks of music I’ve ever experienced,” he wrote me. They did have hit records in New Zealand, and the guitarist Roy Montgomery, then of the Christchurch band the Pin Group, told me that the Fall were “revered” among his cohort; yet according to Smith, there was nobody to receive them at airport (“just five guys with long hair saying, ‘Get in the van!’”), the gig at Mainstreet was half-full, and the review in the Auckland Star called it boring.

*

What was this band? The Fall was a cultural project from Greater Manchester that made not rock but something on the outskirts of it: Greater Rock. Its constituents were Smith—born in 1957 in Salford, just north of Manchester, about half an hour from where he died, in Prestwich—and more than 60 other people, coming and going through the years, many of whom Smith disliked, to the point of psychological or physical violence, and who came to dislike Smith in turn.

From 1977 to 2017 the Fall, as a band, never stopped, despite all its changes in membership; this would destabilize the notion of whatever it was that started—or, that is to say, what a band is. On that topic, one of Smith’s most famous comments is this: “If it’s me and your granny on bongos, it’s the Fall.” I am thrilled to learn that Smith may never have said it. A researcher of facts about the band, who posts as Dannyno on the Annotated Fall website, has discovered that its first appearance in print, in 1998 in New Musical Express, was at best a secondhand quotation—something Smith said to his publicist, who presumably did not write it down but then relayed it, paraphrased it, or made it up, for the NME reporter.

The Fall made songs (if they were songs) that could be, let’s say, deceptively simple in musical structure, from various rock traditions of vamping or repetition or drone, out of the Velvet Underground and the Seeds, and travelled forward according to Smith’s will and intuition as he delivered a body of text. He didn’t seem to be interested in improvisation; there aren’t “solos” in Fall records. (Marc Riley came close to playing them, which might have been one of the reasons he was fired.) But like the leader of a jazz group, Smith would lengthen a section at will and cue the band into a chorus or a new verse precisely when he wanted that to happen.

What was this singer? He seemed more like a chaos theory or a control force than an entertainer. Smith read cult books: Arthur Machen, H.P. Lovecraft, William Burroughs, and Colin Wilson. His lyrics, if they were lyrics, tended to be full of intensely local references and industrial acronyms, contractions and jump-cut syntax, renderings of numbers and letters, stage directions, questions, television references, epistolary headers and footers. They had the natural shorthand gusto of a Pop Smoke song now, but with perhaps a little more interest in distancing himself from the meanings of words and brandishing them as symbols. (Smith read tarot in the late ‘70s, paying for studio time with the money he earned doing it.) In the early ‘80s he liked to use mocking or obscure phrases in doubles, which made them sound like incantations:

“Hey there, fuckface! Hey there, fuckface! Message for ya! Message for ya!”

“Ted Rogers’ brains burn in hell! Ted Rogers’ brains burn in hell!”

“He’s gonna make an appearance! He’s gonna make an appearance!”

“Take the chicken run! Take the chicken run!”

Sometimes they were simply unknowable code: “G-O-H-O-H-O-9-0! G-O-H-O-H-O-9-0!” And toward the end of his life, when the underlying music on Fall records got more leaden and faceless, like folders of royalty-free rock riffs, his words became more molten, gobs of incidental, growled sound-matter: “She strides…Horrible-ah…Facts!….You block hotel area…Without a wedge po-tato! Dreaming! Fol-de-rol! Fol-de-rol!”

To look at his words as text without considering them as sound isn’t right. Rhythmically, he was extraordinary. He could syncopate and swing his phrasing with authority, as he wanted, lined up with the beat or not. It seems to me that his practice of adding an “-ah” to the end of so many words ending in consonants was about increasing the rhythmic power of a line, making it land more profoundly on the ear. After the ’90s he wasn’t doing that so much—he relied more on a catarrhal roar, hissing sibilants, and twangy or back-of-the-throat renderings of wild speech—sounds similar to the way that Texans say “how,” Brazilians say “não,” and French say words that end in -ant. But even when the words emerged slowly and chaotically there was usually a charge or an imminence there, a high awareness of rhythm.

Recently an old friend sent me a couple of thoughts about her work with occult subjects—thoughts that were not related to the Fall, except that they were totally related to the Fall. “From a practitioner's point of view,” she wrote—meaning the practice of tarot, rites, and what she calls “workings”—“‘normal’ folk are wandering around a wilderness of symbol all the time, slightly bespelled, without realizing it.” This is precisely the experience of listening to the Fall, and the subject of many of the Fall’s songs: the wilderness of symbol, a live feed of the wandering through it, the sound of it, and the struggle to realize the meaning behind its symbols.

Back to the basic doubts. What is a band, again? (Most bands’ members have been known to change.) What is an album? (Other than an amount of music long enough for a company to charge more than a dollar or two for.) What is a song? (Other than a matter of copyright.) They are containers made for sorting, for selling, and eventually figuring out what is the best band or album or song, what’s “necessary” or “pivotal” or “classic,” so the rest can be marked as low-priority. The fundamental service of identifying a best record seems to be about saving time, so that those paying attention can be spared the task of listening to the other ones. Is that what being interested in music is about—saving time? (Most of my life I have thought music was about spending time, even wasting it.) If music doesn’t reduce to best records or records at all, nor to bands, albums, songs, eras, years, then what is it?

Perhaps it it is intention. Except that Smith didn’t do intention, as we usually understand it. Perhaps it is something that comes before that: intuition. In any case, why not head in that direction—the pre-container direction? Many others, including John Peel, have said that looking for a best record by the Fall is a blind alley. I’m arguing that the Fall itself is not an isolated case, and suggesting that records themselves may be a blind alley.

In November, Cherry Red released a new, six-CD box set called 1982. I recommend it, even as it makes me aware that recommending any individual part of this band’s work, much less one bounded by a calendar year, makes no sense. It contains all surviving Fall tapes made or records issued from that year—the venerated Hex Enduction Hour album, the much less venerated Room to Live album; some deadbeat audience recordings from clubs around the world; singles and soundchecks and radio sessions, and Fall in a Hole, which is none of those things.

Hex Enduction Hour, and its era, has been the subject of much fascination. Its status as “pivotal” or perhaps best is almost an assumed collective decision, foam left on the seashore. Its making and its reception are covered well in the new book Have a Bleedin Guess: The Story of Hex Enduction Hour, by Paul Hanley, one of the Fall’s two drummers then. Hanley tells the background of each song in clinical detail, with conversational footnotes. (It is both a historical document and a literary one.) It includes a principled discussion of Smith’s use of a racist slur in the song “The Classical,” from the point of view of someone who, conceivably, might have risen up to stop him, no matter what his intentions were in that ambiguously provocative song—symbol-channeling, addressing the concept of tokenism, or otherwise.

A few years ago his brother, Steve Hanley, bassist in the Fall for 20 years, wrote The Big Midweek, a memoir of his time in the band. Brix Smith Start, who played in the band from 1984 to 1989, really co-directing it, and again in 1995-96—she was married to Smith during the first stretch—has also written a memoir, The Rise, The Fall, and The Rise, about one-third of which deals with her time in the band. This is an unusual case: the musicians in a band writing not just its anecdotage but its prime critical and historical texts.

*

By the 1990s, interviews with Mark E. Smith had mostly lifted away from the subject of music. They became a repeating episode of British mainstream-media journalism, a ritual of middle-class self-abasement before an eldritch soul of the nation, or something like that. Though he was not healthy—he finally died of kidney and lung cancer—at least he didn’t represent romance about bad health. He didn’t really represent anything or anyone, not even a cantankerous regular in a pub, because he actually was that man.

Growing up in Prestwich, he had three younger sisters. As he remembered in Renegade, he played a game with them as a child called “Japanese Prison Camp.” He was the Japanese prison guard. His father worked as a plumber, as did his grandfather. He wrote that he liked his father, despite or because of the fact that, as he claims, his father didn’t understand his work. We must allow that his father might have loved the Fall. Why would you put your trust in anything but the sounds, rather than the words, of Mark E. Smith—or for that matter almost any musician? This is the sad refrain of the textual music critic, and the happy refrain of the musical music critic. And those are not the only two options.

Smith was funny in an ungenerous way and also a tormentor; he was disappointing in specifics and often inspiring in general; he cultivated the appalling and intriguing attitude of one who thought he knew how the world works, though his wisdom could seem insulting or jumbled. Regardless of whatever he said and did, he gave others a license to think critically, if only to try to guess his method, which was to betray his lesson, but what can you do?

Take away his specifics of class, generation, alcoholism, and the media he devoured as a young person, and as a type he seems like a friend’s untrustworthy older brother, a haughty mind-fucker—best leave him be, observe him from a great distance. (I am certain I could hear that in his voice when I first heard the Fall, on the radio, in 1982.) I notice that some of my friends also like Smith’s music in spite of a strong aversion to him. One feels he must have been a plain creep. One feels he was tainted by being treated like a national treasure. One feels he became a fascist. They might all be right. So he was a bastard. Good, easier to be a critic around him.

The intensity of Smith’s desire to live outside of norms, for good and ill, is in proportion with the intensity of the research into the band’s music. Any huge pile of anything, no matter how disorganized, becomes a system; a logic can be divined through the detritus. Here are some works of scholarship that know the pile: Katie Hannon’s “The Fall: A Manchester Band?” (on the question of whether Smith’s attitudes and values were regional or anti-regional, which is not the same as “universal”); Mark Fisher’s “‘Memorex for the Krakens: The Fall’s Pulp Modernism” (on Smith as descendent of the paratextual and the “Weird,” via Machen, Lovecraft, Wyndham Lewis’s 1914 poetry-manifesto-graphics magazine Blast, and other cult-lit sources); and the astonishing Annotated Fall website, an open-source explainer to all Smith’s recorded lyrics.

But the creative works generated as a result of the Fall that I like best are the ones that do it from the side. I am thinking of a reckless little book published and briefly sold by the Karma Gallery, by the curator Bob Nickas and artist Nikholis Planck, the source of that “always guesting on vocals” comment quoted above. It is all about the Fall’s record The Wonderful and Frightening World of the Fall, and it knowingly plagiarizes the format of the 33 1/3 series books on individual pop albums. It is an indirect intervention: unofficial, unauthorized, and serious.

Or the English artist Mark Leckey’s 2017 exhibition at MoMA PS1, Containers and their Drivers—its title a quotation from a Fall song—which basically conjured a forest of symbols through a suite of rooms, some with audio-speaker stacks pumping out dance-music and gastrointestinal noises.

Or the experimental novel Popppappp, by Nicholas Currie, otherwise known as the musician Momus, which imagines “Sark E. Myth” of the group the Foul as the avatar of a fundamentalist religion.

*

Starting around 2012 Smith seemed increasingly worn, pale, creased, dehydrated, his features receding and his face crumpling in around a long nose. He continued to wear middle-manager clothes: leather jackets, business shirts, and dress shoes. His complaints became ritualized: England’s gone soft, London’s unspeakable, but even Manchester is ahistorical and middle-class. He preferred Prestwich. (“Strong Irish-Jewish community,” he wrote in Renegade. “You can’t act like a twat.”) As with his teenage hero Colin Wilson, his politics drifted rightward, from socialism to something like English nationalism. Whenever he felt his enterprise threatened by middle-class piety, his alcoholic resentment flared up and out came appeals to working-class respectability. He kept reading books about cult themes: toward the end he often referenced David Eggers’ The Circle.

In some ways he camouflaged himself with the symbols, with the containers. “I’ve always tried to dress smart,” he said during one of the many slack and revealing passages in Renegade. “It’s important. There’s no need to look like a demick. Primark sells some alright stuff at a fair price. Go and shop there. You don’t want to be walking around like an urban scarecrow. Nobody takes a scruff seriously, that’s one thing I’ve learned. It’s all fine dressing in this anti-fashion style if you’re on the piss in Camden Town, but imagine doing business with a berk dressed like a vagrant…it just doesn’t work.”

Let’s contain this: Primark is an Irish-English chain of affordable-clothing stores much like H&M; its largest shop is in Manchester. Here is a rock singer doing the opposite of what rock singers do: he is telling you to pull up your socks and look presentable. Camden Town is in London, which he disliked. “Demick” (or demic) is northern slang meaning a useless person or thing, particularly with reference to trains, vehicles, and, as I understand, the shipping-container industry.

Neither Mark E. Smith nor his father left Greater Manchester. “In my game, theoretically I should have moved from the place where I was born,” he said during an interview in 1985, before the days when his sentences trailed off. “That’s a tradition all over the world, isn’t it? If you think you’re some kind of artist, you get out of the place straight off, don’t you. But I never could.” By the place he was born, he meant North Manchester. Many of his listeners would be puzzled by this distinction. He claimed, more and more, not to like Manchester, even as he (unwillingly) represented it. Can that be right? Yes: go back to Katie Hannon’s essay, and to the later interviews. It is.

I’m American, and I kept my distance from Smith. My grandmother came from Manchester and she was impossible, but this does not qualify me to understand Mark E. Smith’s hyper-regional spite. Still, if your art is about opprobrium, I can understand your wanting to be near a source of it. If you’re suspicious of records, I can understand you wanting to make lots of them anyway: their number destabilizes their individual authority. I suppose I can also understand the paradox of being a romantic figure within your own mind—an existential hero like the ones Colin Wilson wrote about in The Outsider—and resisting the call to act like an outward paragon of any kind, morally or artistically. The daughter of a friend of mine lives not far from Smith’s old home in Prestwich. She says he was a tosser.

If I am describing the Fall as an anti-container band, I still worry that I have not chosen the perfect example. I could be describing a different track from Fall in a Hole— “Prole Art Threat,” whose lyrics, if they are lyrics, were written as a fragmentary screenplay, or possibly a surveillance transcription, and in which Smith’s delivery, on that night in Auckland, is both distracted, fragmented, rhythmic, full of mutterings, sneers, “-ah”s, growls, stutterings, side commentary, and other paralanguage—at one point he seems to yell instructions to the sound-person in mid-flow. But I am content that the Fall isn’t really understood by individual examples.

If there is an essence of the Fall, it is surely bigger than what is meant by “1982.” Maybe it is this remark of Smith’s, excerpted from an interview in Q magazine in 2015, and quoted in Have a Bleedin Guess: “There’s always some cunt who wants to ask me about a masterpiece I made in 1982.” Surely he was referring to Hex Enduction Hour. The thing to do is to look not at the revered thing but the thing off to the side. Fall in a Hole is a thing off to the side. Nobody calls it the Fall’s best record. Singer/not a singer. Group/not a group. Year/not a year. Record/not a record.