Super Ape in Indy

Adrian Matejka

July 3, 2017

Indianapolis is welcoming and provincial, curious and recalcitrant. There are only seven skyscrapers downtown, and on any given day it might seem like nothing is happening, save for people lounging in porch swings or mowing their lawns. It can be quiet here, which is sometimes confused with intellectual or creative stagnation. But this imaginative and complex city birthed the Ink Spots and jazz greats Wes Montgomery and J.J. Johnson. It was home to David Baker, Mari Evans, and Etheridge Knight while they created some of their most sophisticated and political work.

It’s a sprawling place with enough room and enthusiasm for cultural institutions like the Free People’s Workshops and Indy Jazz Fest, and for more unexpected cultural pop-ups, often from artists and musicians working their way through the Midwest. The city’s (sometimes) openness, (sometimes) willingness to burn one down in the name of righteous harmony and poetry makes Indy the perfect place to catch a show. That’s how I got to see Parliament, Fishbone, and Rakim for next to nothing. That’s how I stumbled on Lee “Scratch” Perry last August celebrating the 40th anniversary of his dub reggae opus Super Ape.

Perry performed at the Vogue in Broad Ripple. The club, like Perry, has an eclectic and extensive history—it was an upscale movie theater from its opening in 1938, became an X-rated theater in the early 1970s, then reinvented itself as a night club with DJs and live acts in 1977. Blondie, Johnny Cash, The Ramones, and Rihanna have played the Vogue at one time or another.

The surrounding neighborhood of Broad Ripple has always been an Indianapolis outlier: longtime home to Comic Carnival, record stores, and one of the first coffee shops in the city. Before it tried to remake itself as entertainment district, Broad Ripple was also where you could find the collectors, arguers, and list makers of music. In the 1980s, I would stop there for comics and coffee, then ride my bicycle just a little further to Rockin’ Billy’s, one of the only record stores in Indy that sold rap 45s and dub music.

It was the first place I remember seeing Lee Perry’s name on a poster. I had no idea who Perry was, but I loved that his nickname was “Scratch,” as I was trying (and failing) to learn to be a rap DJ. That his nickname refers to the idea of “starting from scratch” was lost on me then, and in my memory, whatever poster was actually there has been replaced by one of those red, yellow, and green cardboard replicas record stores sell of great reggae shows from the past, almost always Bob Marley.

I admire Perry’s dub stylings for their absurdity and innovation as much as their bass lines and back beats. His work is an evolution of (or maybe deconstruction of) roots reggae—that slow, bass-driven music from Jamaica that, in its blandest form, is featured in commercials for Caribbean vacations and in bars when they want to make the place feel more like summer. Dub, however, emphasizes the rhythm, production, and melody over lyrics in ways that are meant to be simultaneously tranquil and inventive. The music has a loose kind of propulsion, but it’s in the echoes and reverbs, not words.

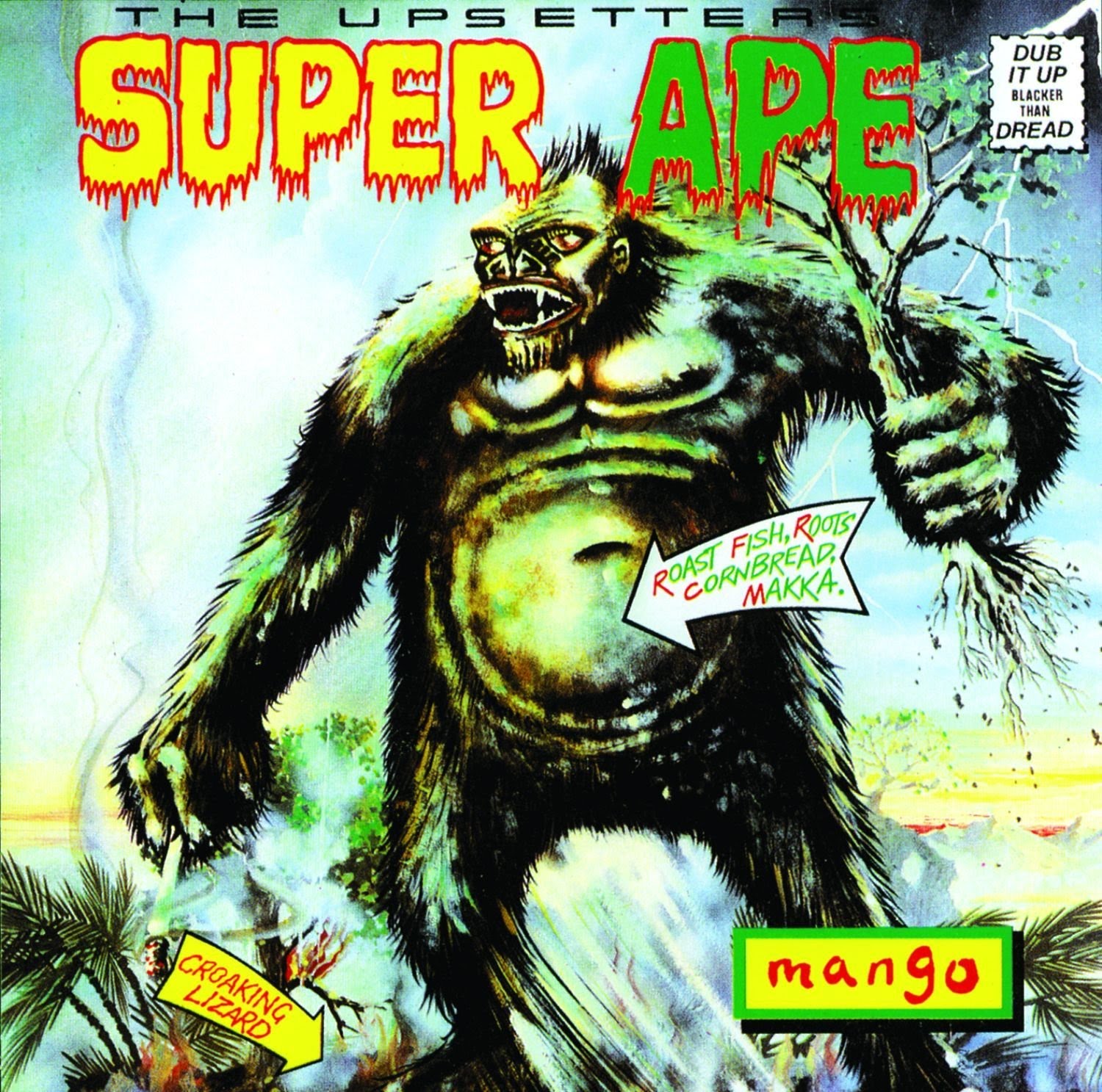

Perry was messily influential in the creation of both roots and dub reggae, and Super Ape is the kind of bright, perfect album that attracts hardcore reggae fans and dabblers alike. When asked how dub evolved, Perry said, “We liked to record the drums and bass first, to get them perfect. The other instruments would be put on afterwards. But sometimes the rhythm track would be so fucking perfect that we’d forget about the other parts and just play about with the drum and bass.”1

Just playing about with the drum and bass: the essential pieces of disco and funk, both of which were also at their apex in the 1970s. Super Ape has many get-funky moments, too, though they are obfuscated with echoes and reverb and are slowed down significantly. Perry’s sonic fragmentation and angles of protest add even more power to the album as it leans on harmonies and choruses, like roots reggae, to create a pure statement of innovation and artistic perspective.

Perry worked with some of the most gifted musicians in Jamaica in his Black Ark studio. His studio band, The Upsetters, included brothers Aston and Carlton Barrett who eventually left to become the rhythm section of The Wailers. He also produced and wrote songs for Bob Marley and was instrumental in Marley’s early musical ascendance. The two had a falling out over money, but remained connected, in part because both Marley and Perry were products of the complex racial and economic politics in Jamaica. The music they were creating—Perry pushing further into dub while Marley wrote the most popular roots reggae then or now—were extensions of the postcolonial social and economic pressures in the 1970s.

Something else they shared: Marley and Perry took the fundamental expectations of reggae and turned them inside out. Marley achieved his greatest artistic success by mixing roots reggae with British rock and American funk and R&B on Exodus. Super Ape is Perry taking his tenets of dub and layering them with soul and leftover psychedelia—a mix of styles that reflects his creativity and frantic capaciousness. His wide-ranging catalogue is almost impossible to classify, spanning five decades and more than a few record labels that have gone belly-up.2

But what might be even more complex to chart are the breakthroughs Perry made in recording and mixing that are the foundations of a range of contemporary genres. His emphasis on spare vocals, reverb, samples, and a dependence upon rhythm instruments became one of the engines behind disco and early hip hop. The great rap innovator Afrika Bambaataa said that Perry’s futuristic sounds and unique style of Jamaican toasting informed and inspired the early hip hop DJs and were central to the creation of rap music. Perry’s direct influence extends even more broadly; he later worked with the Clash, Paul McCartney, the Beastie Boys, and more.

.jpg)

None of that mainstream shine carried over to Perry, of course. He remains a mostly obscure figure outside of music heads and reggae deep-divers. And if I’m being real, the Super Ape anniversary show had no chance of taking on the immortal veneer of one of those Rockin’ Billy’s posters any place except for in my brain. What was it that I—that we—as Perry’s audience, expected? For him to be the same artist he was at 40, chanting and agitating in front of a packed house? For him to retell the story of why he burned down the Black Ark studio to set it free from evil spirits? Or was it enough just to be there, to bear witness to whoever he is now? Grandfather. Elder. Ancestor in dub and strut.

What we got was 80-year old Lee “Scratch” Perry in a track suit with a neck full of gold chains. He wore big, gilded sunglasses and his beard and hair were dyed bright red. A golden, jeweled chalice in one hand, the mic in the other, finding his way back to and through music he’d recorded when I was five years old. The show was thinly attended, mostly by older folks in tie-dye. There were a couple of venders selling handmade hemp jewelry and shoulder bags festooned with cowrie shells. There was a white woman with dreads selling jerk chicken. Lee Perry doesn’t travel with a full band or his own DJ, and to say it was a great show would be generous. But the show was historic and transcendent—the way Kobe Bryant scoring 60 on 50 shots in his last game is historic and transcendent.

Behind the stage, video flashed the expected Rastafarian iconography—spinning pot leaves, lions with majestic manes, Marcus Garvey and Haile Selassie—but interspersed throughout was dash-cam footage of downtown Indy. For an hour and a half, Perry paced in front of these visual allegories of religion and history, chanting and bouncing as he performed the entire Super Ape album. He no longer drinks alcohol or smokes marijuana, but that didn’t stop people from throwing joints at him and it didn’t stop him from pausing occasionally to smell one of the larger ones, running it under his nose the way a captain of industry in a movie savors his Cuban cigar.

Perry performed from muscle memory—he’s been doing this for over 60 years—but there was awareness and wisdom in his performance, moments when he would slow down and linger over a particular phrase or chorus, as he did in “Zion’s Blood” (“Zion’s blood / Is flowing through my veins / So I and I / Will never work in vain”) to highlight dub’s historical and emotional necessities. Or when he performed “Underground” (“Underground roots /are collie roots”) and then he continued to sing the wordless chorus “dah-dah-da-dah, da-da-da-dah” over and over in a kind of jazz riff to be sure the literal and metaphoric roots were understood by all.

He pointed at the crowd with a kind of surprised ownership, to all of us dancing or trying to dance, as if to say, “I got you all moving?” The projections behind him of the Indianapolis skyline wobbled with every bass reverberation and echo. We were all just playing about at our own paces, the way that most things happen in Indianapolis, dub or not.

Somewhere in the middle of “Underground” it became clear that whether or not the show was classic was never the point. The thing that felt most important, then and now, was the timelessness of the music itself is. Super Ape sounds as brand new right now as it did in 1976. Maybe that is because Perry’s dub techniques are so ingrained in rap and pop production that they lend a contemporary shine to any song that implements them. Or maybe it was Perry himself, giddy behind those golden glasses, refusing be 80, refusing to let Indianapolis be mistaken as anything but the center of the dub universe for a few August hours.

- http://www.uncarved.org/dub/scratch.html

- For an in-depth overview of Lee “Scratch” Perry’s discography: http://daily.redbullmusicacademy.com/2014/02/lee-scratch-perry-album-guide