M.I.A. and the Defense of Nuance

Fariha Róisín

July 30, 2018

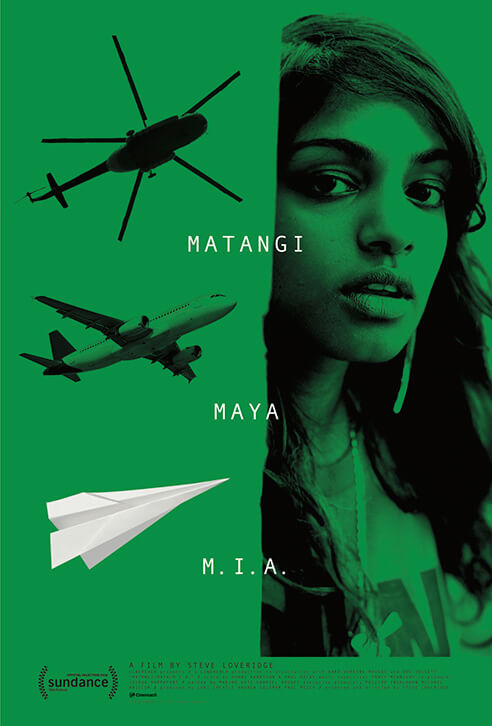

This spring at MoMA, I moderated a conversation between M.I.A. and director Steve Loveridge on the occasion of the upcoming documentary Matangi / Maya / M.I.A. When first asked to do it, I was tentative. I hadn’t listened to Maya’s work in a couple of years, after she somewhat embarrassingly responded off the cuff to a question about Black Lives Matter: “Is Beyoncé or Kendrick Lamar going to say Muslim Lives Matter? Or Syrian Lives Matter? Or this kid in Pakistan matters?”

I was frustrated at her insouciance. Those examples aren’t mutually exclusive; saying black lives matter is saying that all lives matter because when black life, at its core and foundation, is valued, then so is all human life. To me, muscling in fake humanity—with an oh, well, all lives matter—only proved how little she knew about the menace of this particular kind of racism. I felt betrayed by her.

I’d been a fan of Maya’s work since my early teens when I first heard her debut album Arular, named after her father. Finding her was elliptical magic, a sense of exhilaration. It was the inhalation of seeing another human being like you, but acutely like you—not the ubiquitous successful auntie type, but fully-fledged dynamite. I can still remember the thrill I felt when I saw the video for “Jimmy.” A golden constellation, palms faced towards the sky, our very own demi-Goddess, like Gaia, or more accurately Kali herself, arching her back, cocking her neck, lips glossed like sticky tar. Her boredom palpable, but her vision magnetic.

Against the bomb-sampled beats and the pop sounds of the Global South, Maya rapped and sang with ballistic shyness. Her appeal was layered. She was attractive in a relatable way, as in she wasn’t a brown girl that looked white, she was a brown girl that looked like us. Decked in prints of yellow and pink, or the infamous black and sheer collage she wore at the Grammys, a full nine-months pregnant, belly whopping, tight at the seams, deliciously incandescent. The way she navigated fame felt like we had made it. We South Asians. The many of us that so desperately craved to both be seen, and applauded.

She roused something deep inside of me, something that felt like pleasure, like hope. She became the gilded example, the artistic immigrant success story you used against your family at gatherings, slurring declarations of admiration, huffing mad love. She’s the one who made it, ushering in our collective futures, allowing us to (finally!) boast creative desires of our own.

But, language is important. What you say—and how you say it—is a small, but radical act. Maya had become an (the only) avatar of South Asian representation. Her visibility was announcing to the world that we could win too. She was our bright asylum, ushering us into spaces we’d never been allowed to enter—and we needed her to do us right.

Needless to say, I was apprehensive about the interview. I told her publicists my only stipulation: I would have to ask her about her anti-blackness onstage. They agreed.

*

Cancelling people is exhilarating, especially when it’s done by marginalized folks, those who so often experience the world through white supremacy—sometimes as a soft and subtle barrage, other times through vicious and terrifying means. The ability to dictate someone’s fate, when you’ve long been in the shadows, is a kind of victory. Like saying “Fuck You” from underneath the very heavy sole of a very old shoe. But while outrage culture has its merits, nuance has evaporated. So often it involves reducing someone to their mistakes, their greatest hits collection of fuck-ups.

In her song “Best Life,” Cardi B raps:

“That’s when they came for me on Twitter with the backlash/ "#CardiBIsSoProblematic" is the hashtag/ I can't believe they wanna see me lose that bad...”

According to writer Najma Sharif, this is her response to being cancelled for a now-infamous Twitter thread detailing her colorism, orientalism, and transphobia. Most recently, after her song “Girls” with Rita Ora was also deemed problematic, she made a statement: “I know I have use words before that I wasn’t aware that they are offensive to the LGBT community. I apologize for that. Not everybody knows the correct ‘terms’ to use. I learned and I stopped using it.”

Cardi brings up something that I keep coming back to: How accessibility to political language is a certain kind of privilege. What I believe Maya is trying to say is that American issues have become global. What she lacks the language to say is: how do we also care about the many millions of people around the world who are dying, right now? Why does American news, American trauma, American death, always take center-stage?

There are things we need to agree on, like the permutations of white supremacy, but are we, societally, equipped for social media being our judge, jury and executioner? I started to realize that the schadenfreude of cancelling was its own beast. It erases people of their humanity, of their ability to learn from experience.

This brings up the politics of disposability. How helpful is distilling someone into an immovable misstep, seeing them not as a person but as interloper who fucked up, and therefore deserves no redemption? How helpful is to interrogate a conversation, but not continue it? Is telling someone to die, and sending them death threats, or telling them they’re stupid or cancelled the way to do it? Who, and what, are we willing to lose in the fire?

M.I.A. and Cardi are similarly unwilling to conform to polite expectation. They both know that relatability is part of their charm. They are attractive women who speak their mind. This, in essence, is privilege, too—which then requires responsibility. The difference is that Cardi apologized.

*

Bad behavior from celebrities is not new, it’s become a trope: from Johnny Depp trashing his hotel room in the ‘90s to allegedly beating his ex-wife Amber Heard. Throughout, it’s important to understand how the powerless have long existed in the margins. These days, because of social media’s newfound democracy, we see Scarlett Johansson getting called out for her lack of desire to understand why it might be problematic for her to play a trans person; Or when Mark Duplass asks us—“the liberals”—to engage with the racist Ben Shapiro; Or when Richard Dawkins, a fundamentalist atheist, is critiqued for his Islamophobia. We, the people, finally have a voice. This is power. But with power comes responsibility.

*

Growing up in Australia, I experienced an incredible amount of racism. Whether it was being called an ugly brown bitch, or routinely experiencing Islamophobia vis-a-vis strangers, acquaintances, and friends. My body was vilified against the backdrop of pristine-beach whiteness. I was unwanted, and I felt it in my pores. But it took me coming to the United States to understand racism on a larger, more insidious scale.

When Manna, my Iranian-Australian childhood friend, is in Australia she’s seen as a “FOB.” Fresh off the boat. Too ethnic. In America, she’s read as white. We grew up together after 9/11, both immigrant kids, both adjacent to Islam in different ways. It felt like displacement: being bullied by our friends, people calling us terrorists; men cornering us on lonely streets and threatening us, telling us to go back to our country; never ever fitting in because we weren’t white.

It gave us an edge. At 14, we started the social justice club in a school of fifteen hundred. We were nerds who read Chomsky, The Autobiography of Malcolm X. We hosted talks on the deaths of incarcerated indigenous inmates, and the brutality of the Australian penitentiary system (which is, ironically, similar to the U.S.). In largely white classrooms, we bonded over wanting more from our world, and knowing there was more to the violence we experienced. We wanted context. We wanted to thrust that context onto others.

My whole life I was too dark, but in America I’m brown, and therefore part of a larger, more nefarious notion of the model minority myth: the legacy of brown folks to exaggerate their inherent migrant worth. An insistence that relies upon our juxtaposition against black Americans. It took me years to learn that my experience, as a brown person in America, would never be the same as black folks. That the racism I had experienced in my lifetime would never be comparable.

*

“Is Beyoncé or Kendrick Lamar going to say Muslim Lives Matter? Or Syrian Lives Matter? Or this kid in Pakistan matters?”

In 2016, when Maya made these comments in an ES Magazine interview, I remember being frustrated that she only accentuated the divide between non-black people of color and black folks, partially because so often we (Asians) say dumb shit.

The dumb shit I’m referring to w/r/t Maya is not only her tunnel vision when it comes to the complexity of race (plus the void and difference between black and brown folks’ experience) but also the incapacity—or stunted unwillingness—to further self-reflect on her positioning.

Because of her insolence, I had considered Maya undeserving of my alliance. Her lack of inclusivity and disregard of the complexity of political identity, especially in North America, was abominable. As a woman who had found success within the black mediums of rap and hip-hop, her smug disregard felt brash. It felt lazy.

But, as I watched the documentary on her life, I also began to see her complexity. One thing that strikes me about Maya is her personal perseverance. Her family went through hell to get the U.K. Her father’s political affiliations forced them to flee Sri Lanka. Arular was a revolutionary, and thus deemed a terrorist. He was absent her whole childhood. At one point in the film she describes riding on a bus in Sri Lanka with her mom. When the bus jerks forward, the policemen standing alongside casually sexually assault them in broad daylight. Her mother, Mala, warns Maya to stay silent, lest they both be killed. Her reality—of physical threats, of early loss—is stark. As she recalls the details in her candid, detached drawl, you imagine her grappling with the past like a lucid dream.

Herein lies Maya’s dissonance. She is the first refugee popstar, which allows her to subsume a state of Du Bois’ double consciousness. She is neither this nor that, she is a mixture of both East and West. Her experience seeps into her music like a trance, and these definitions are vital to understanding her.

She is agonized by the realities of war, of being an unwanted immigrant who fled from genocide into the frenzied hells of London, only to be pushed into a mostly-white housing estate system, replete with Nazi skinheads. “A tough life needs a tough language,” Jeanette Winterson writes in Why Be Happy When You Can Be Normal?, her memoir about her abusive stepmother. As I watch the documentary, I wonder, again, if what Maya lacks most is language.

In the current political climate, where Syrian refugees are denied entry into the U.S., and the Muslim Ban, or “Travel Ban,” is an attack on the very notion of being different in America, I began to understand this other part of Maya. How angry she might be for the lack of articulation when it came to refugees, when it’s still very much an issue. She came to music to survive. Art was a way to dislocate from the trauma, to inoculate herself from the past, and provide a new, vivid reality that was both about transcending where she came from, whilst also creating a platform to speak to her roots, to her lineage, to her people.

Tamil is one of the oldest languages in the world. The people that speak it are, right now, being wiped out.

Her understanding of race comes from the victim’s perspective. She not only experienced white supremacy in her work, but was forced out of the country where she was born. Someone like her was never supposed to succeed. But, whether it’s Bill Maher mocking her “cockney accent” as she talks about the Tamil genocide, or the New York Times’ Lynn Hirschberg claiming her agitprop is fake because she dare munch on truffle fries (which were ordered by Hirschberg), Maya has been torn apart by (white) cultural institutions and commentators. You can see how these experiences have made her suspicious in general, but also particularly suspicious of me, a journalist.

Thing is, she’s been burnt by us too—by South Asians. So many of us walked away, attacking her instead of building a dialogue. Her compassion, therefore, is partially suspended. It’s as if she’s decided, vehemently—because she’s deemed herself to not be racist, or anti-black—that the conversation ends. She feels misheard, misrepresented. For her, it’s not about black life mattering or not mattering. It’s about prioritizing human life, about acknowledging human death. But, in America, that gets lost.

You can understand Maya’s perspective without agreeing with her, but I had another question. How do you hold someone you love accountable?

*

The talk itself was many things: awkward, eye-opening, disarming. When I asked about her alleged anti-blackness, she brought up Mark Zuckerberg as evidence that she was set up... by the internet. That her online fans should know that she’s not racist, so that perhaps her one-time friendship with Julian Assange was why she was being attacked online. Her incomprehension that people could be upset by her remarks reflected her naivety about how the internet kills its darlings. Two weeks prior to our meeting, Stephon Clark was murdered, shot twenty times in the back by two police officers. To this she responded: “Yeah, well no-one remembers the kid in Syria who is being shot right now either. Or the kid that’s dying in Somalia.” It made me wonder if she was unwell, not on a Kanye level, but just enough to lack the mechanisms it takes to understand perspective.

Backstage after the talk, she said, “I don’t know why you asked me those questions.” I told her that I thought critique, when done with care, was an empowering act of love. I needed clarity for our community’s sake—many of whom felt isolated by her, a cherished South Asian icon. We need answers from her because we are all trying to grapple with our love and frustration with her.

I don’t want to absolve Maya. What I’m more interested in is how we can say “problematic fave” while acknowledging that we are all problematic to someone. Is there compassion here? Is there space to grow?

*

In They Can’t Kill Us Until They Kill Us, Hanif Abdurraqib writes, “There are people we need so much we can’t imagine turning away from them. People we’ve built entire homes inside of ourselves for, that cannot stand empty. People we still find a way to make magic with, even when the lights flicker, and the love runs entirely out.”

In the recent months, I’ve re-examined Maya with sad enthusiasm. The beginning riff of “Bad Girls”: a women in full niqab racing a car through side swept dunes. Without question, it’s an aching kind of visibility, but the tenor is different. Listening to her now it feels weighted, changed.

Laconic and aloof, I remind Maya on stage that anti-blackness is not an American issue, it’s universal. Perhaps it’s ego, or shameful anger, but I know she cares. Before she begins to speak I realize that you have to build empathy when someone fails you. That they’re not yours to own. You have to try your best to talk to them, and that it’s never helpful to reduce them to a punchline. I believe in Maya’s possibility to grow. I believe in the possibility of change. Maybe that’s my own naivety, but it’s also my political stance. It’s not about compromising ideology, or even making space for the existence of those ideas. It’s about creating dialogue.

She begins to speak, and I listen. Holding space for her when I can without biting my tongue. But, mainly, asserting myself as hard as I can, with as much compassion as the situation deserves. We are sisters in this fight, and we’re butting heads—but both critique and accountability are important. So I remind her with a glance, with an interjection, that I’m here to talk, too.