Who is Michael Jang?

David O’Neill

November 5, 2019

Photographer Michael Jang is the subject of a new monograph, out this fall from Atelier Editions. The book’s title asks Who Is Michael Jang? Here are thirty possible answers.

Jang is a nine-year-old San Francisco Giants fan. He takes a picture of his hero, Willie Mays. The image is a little off-kilter, but it beautifully captures the Say Hey Kid mid “hey.”

Jang is pure California.

Jang is a 22-year-old student visiting his extended family, second-generation Chinese American immigrants, in Pacifica, California. It’s 1973. He’s been taking photography classes in Los Angeles and, like many art-school kids on break, he documents his relatives with an eye for their eccentricities. He also poses himself: In “Self-Portrait Eating Apple Pie,” Jang deadpans the viewer, gazing at the camera with his fork hovering over the patriotic pastry. The flash-lit black and white image, like many Jang has made over the course of his 40-plus year career, shows him enamored of national myths and quietly assessing his place in them. “As American as . . .” before you can finish the familiar phrase, you’re distracted by the aquarium: a large fish photobombs the top of the frame. Here, as always, Jang undercuts self-seriousness, cracking a joke just when the image starts to feel too earnest. My real question: How did Jang get the koi carp to give the camera a wryer look than his own?

Jang, a longtime commercial photographer, was discovered as an artist in 2002, when he brought his work to SFMoMA for an open-call portfolio viewing. Curator Sandra S. Phillips remembers: “We were genuinely thrilled to have found not only a wonderful unknown photographer but a delightful new friend.”

“He speaks in your voice, American, and there’s a shine in his eye that’s halfway hopeful.” —Don DeLillo, Underworld

Jang is hopeful, playful, and cautiously heedless. The artist with a shine in his eye (an American as apple pie).

Jang is a fake press photographer. To gain entry to celebrity parties, he made sham passes from Rolling Stone, the New York Times, and the San Francisco Chronicle. Really, he was always his own boss and his own employee, even when he assisted the likes of Norman Seef, a big deal album-cover photographer, or Annie Leibovitz, who is Annie Leibovitz.

Jang is a student of Lisette Model. In the ’50s, Model had taught Diane Arbus, who proved to be a moody student. Model later noted: “The things I said would make her start to cry. She would burst into tears, she said she was so moved by them.”

Jang has no public record of tears.

Jang is quirky but deep. “Self-Portrait Eating Apple Pie” is part of The Jangs, a 1973 series that at first seems just loopy but then reveals a greater intimacy and depth than most dispatches from the wilds of suburbia. Like Larry Sultan in his ’80s series Pictures from Home, Jang hooks the viewer with kitschy Americana. When the novelty wears off, there’s more to see—and remember. Looking at these photos, I taste icy generic ginger ale, which must be my own suburban projection, circa 1982, far from California. The Jangs provokes such reveries because their flat specificity exactly evokes a particular time and place. You wonder: What are the few visual details—decor, fashion choices, products, facial expressions—that could convey my family’s whole deal?

Jang knows the manic silliness under the still suburban surface, the aggressive fun one has to make when boredom reigns. That might mean stretching a sandwich bag over your face, skiing indoors, messing around with BB guns in the bedroom, goofing off on crutches in your underwear, harassing the dog, smoking constantly, reading Mad Magazine, choosing loud wallpaper, playing golf in the dark backyard, blasting glam records, or being a maniac for the NFL. To capture this menagerie, Jang splits the difference between Arbus and Garry Winogrand.

(See also: Matt Damon’s debut, Over the Edge, 1979.)

Jang is, eternally, the art-school proto-punk home from university, Bowie record under one arm and the VU under the other, Nikon around his neck. Notable glasses. Whether he’s capturing his aunt Lucy watering flowers or stoned undergraduates or would-be weather anchors lining up for a tryout or Johnny Rotten or teenage garage bands, Jang’s tone is consistent: impish and knowing. He doesn’t posture. Though clearly influenced by Arbus, Winogrand, and Lee Friedlander (three staples of his early art education), Jang had his own aesthetic down by age 22: life-of-the-party visual pranks (that fish . . . ), decisive moments galore, plus muted social commentary (if you want it), a flash-drenched paparazzo tonality, and pixel-perfect, dynamic composition that leads you through the frame, his choreography, an understated stunt, climaxing like a perfectly timed firecracker in the boy’s bathroom.

Jang has committed to the bit.

Jang knows how to punch up a joke. He took a black-and-white picture of Aunt Lucy wearing a green shirt that says “GREEN” in block letters. He titled it “Lucy Wearing Green.”

Jang patiently hung around his family’s bathroom, like Ron Galella in the bushes outside Jackie O.’s penthouse. Finally, the moment he’d been waiting for: Chop Chop the Siamese cat clambers out of the toilet bowel.

Jang has always loved celebrities.

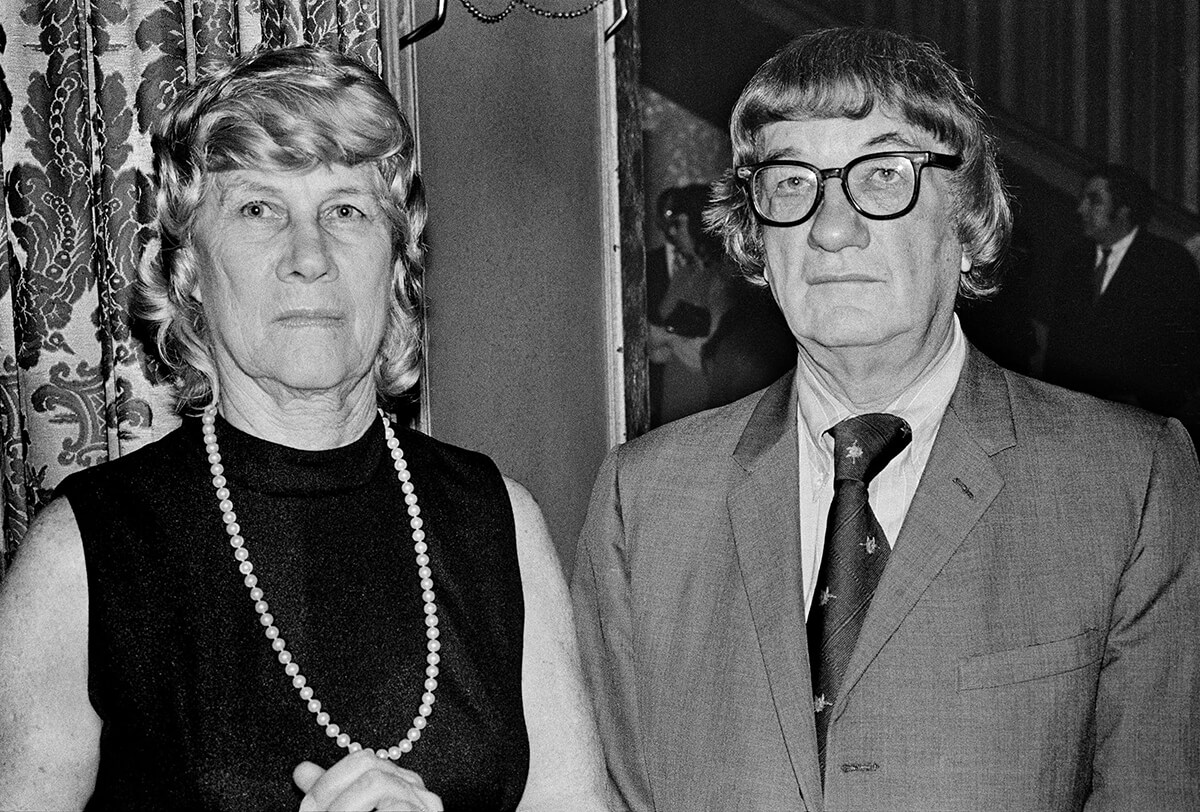

Jang scams his way into galas at Beverly Hills Hilton. The 1973 series Beverly Hilton includes Frank Sinatra, Jack Lemon, and Bea Arthur. (Bea once put the whole question of “self” to bed: “I’m not playing a role, I’m being myself, whatever the hell that is.”) But it’s the unfamous who make the best subjects: Jang is Cassavetes–like in his focus on strained coupledom, shooting heterosexual partners dancing in florid dismay.

Jang shows us that wealth looks ugly up close—even lit by his sunny M.O.

Jang briefly got caught in the gears of history. Making the series San Francisco, he prowled the helter-skelter streets of the 1970s Bay Area. But his work repels dread and paranoia and can’t quite capture the burnt feeling of failed revolution; most of the images read as amused, if baffled. He’s affable, eager to show us the slightly absurd—to make us chuckle (not laugh)—which makes one photo in the sequence genuinely shocking. At first your eye is drawn to an apparently on-fire sleeping bag in the lower left of the frame. The disquiet builds as you take in the spilled wheelchair and the crowd of men watching the fire. You have to flip to the back of the book, where the titles are listed, before you understand: “Suicide, Golden Gate Park.” Another concealed body appears a few pages away. Harvey Milk, California’s first openly gay political representative, assassinated by a man named Dan White, who claimed eating Twinkies was a symptom of the underlying mental disease that caused him to murder Milk and Mayor George Mascone, is pictured in a body bag. The shot is completely inert, drained of the twisted backstory and of sadness or political rage. (I was glad that there was no schtick.) Jang seems unable to say anything about this monumental event—save for the fact that he was there, camera in hand.

“A photograph is a secret about a secret.” —Diane Arbus

Jang doesn’t want to bum you out. After San Francisco comes Summer Weather (1983), in which Jang plays August Sander for the would-be weather reporter set. The hair is simply astounding. Jang framed everyone the same way, straight-on head-and-shoulders compositions with the subjects looking you directly in the eye. Jang has no typological theories. His portraits prefer pure personality—of which there was plenty in the ’80s local-news scene.

Jang sees through people. In my favorite Summer Weather portrait, a bald priest with a mustache stares at us with eager-to-please eyes. The push-broom ’stache with flecks of grey suggest a burgeoning midlife crisis, as does the man’s essence of job-interview-level gameness. If he’d gotten the gig, he’d probably show up in an ’83 Corvette.

Jang is fashiony, with an eye for style. All good snapshot photographers know how to work in a modish hook. Jang’s vision goes one better; he takes real good-natured pleasure in how people put themselves together. Aunt Lucy in that green shirt; a young bearded shutterbug, collar opened to the third button, wearing his plastic camera as proudly as if it were a gold chain; William S. Burroughs looking roguish in a three-piece suit, tipping a slim, dark fedora.

Jang is anti-fashion. He likes punk rock. In 1977, while getting an MFA at the San Francisco Art Institute, he went to Bay Area shows, documenting local bands such as Pearl Harbor and the Explosions, the Dills, the Mutants, and out-of-towners including Devo and the Sex Pistols. Jang saw the Pistols’ last performance on January 14th, 1978. Introducing the encore, Johnny Rotten told the audience, “You’ll get one song and one song only, because I’m a lazy bastard.” The Pistols played “No Fun,” a nearly seven-minute exercise in true joylessness. (“Have you ever gotten the feeling you’ve been cheated?”)

Jang is lucky. On January 15th, after the Pistols had secretly split, Jang ran into Rotten at the Miyako hotel, where Jang had been hired to photograph the employee of the month. Instead, he shot Rotten. The singer drank and smoked in a booth, looking small and very unlike an antichrist. He was, unbeknownst to Jang, contemplating the end of an epoch.

Jang was a commercial photographer for many years, and it shows. Although the photographs in Who Is Michael Jang? were not taken with any audience in mind, and definitely not for “clients,” they’d still be at home with any branding endeavor or product-adjacent creative category. They tweak expectations, but happily, and only enough to make you feel good. They signal authenticity but they’re not too authentic, ie., déclassé. Maybe it would be better to say “Jang is the platonic ideal of the commercial photographer,” because such work usually gets old, but Jang’s has always, and will always, look cool, or uncool in the right way.

Jang is a sly observer of identity, that vexed category. See: “Self-Portrait Eating Apple Pie” or really any shot from The Jangs, as he frames a memory of his childhood, which he’s described as “Leave it to Beaver time.” See: his interest in the most performative personalities, the punk, the TV weatherman, the celebrity, the debutante. See: the other self-portraits in Who Is Michael Jang?, including the cover selfie taken on a street called “California.” See: “Self-Portrait for Popular Photography Magazine” (1974), in which Jang plays with a stereotype, holding chopsticks and a rice bowl, looking at the camera in a way similar to “Self-Portrait Eating Apple Pie,” only this time that look reads as a dare and a pointed question. The book’s title has many such queries nested within it. Now nearing 70, Jang is taking stock, looking for the through line, presenting and re-presenting himself, defining his life by what he’s noticed in others. Who Is Michael Jang?, like many monographs, is a disguised autobiography; we see what Jang saw and sense not only the man behind the camera but also the long stretch of years between that Jang and the one who is putting the images in front of us now. In case we fail to grasp the message of Jang’s freewheeling oeuvre, the book’s last pages state his thesis outright. In all-caps text on an all-white spread there’s a bald statement: MICHAEL JANG IS GOOD FOR YOU.

Michael Jang took some perfect photographs. What more can we ask?

Who Is Michael Jang? is published alongside the exhibition Michael Jang’s California at the McEvoy Foundation for the Arts, on display through January 18, 2020.