Middle Sister

Audrey Wollen

March 10, 2020

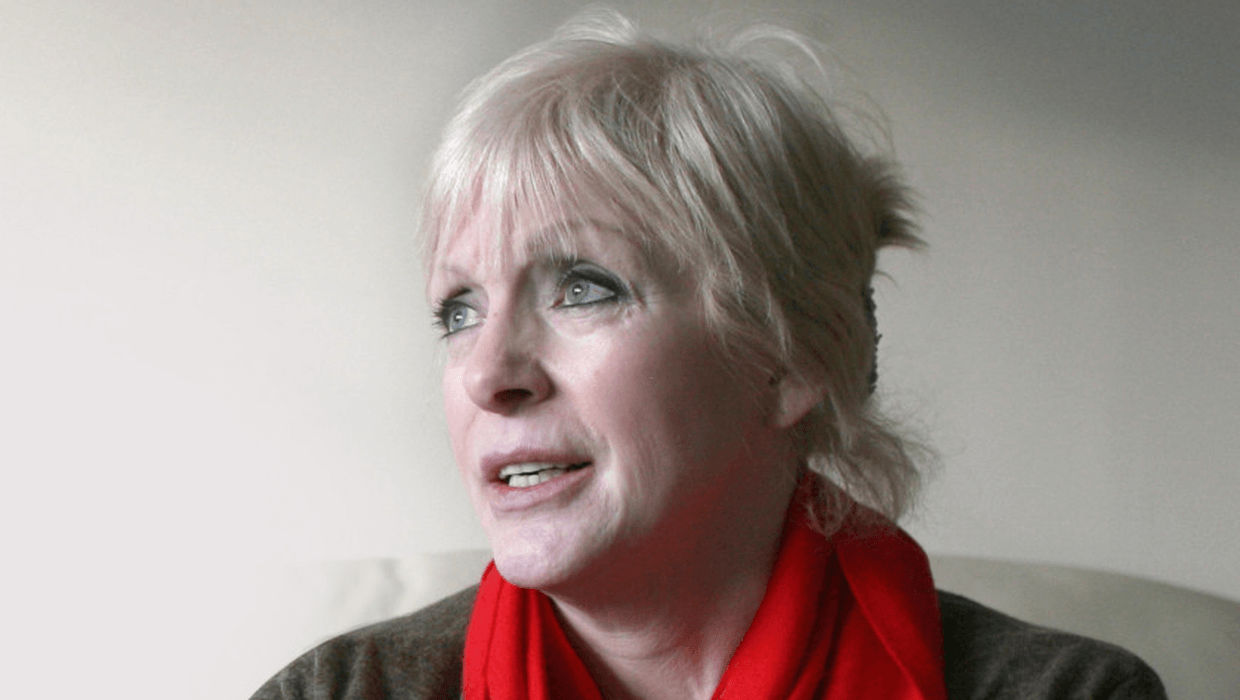

In her middle age, she looks a bit like Marianne Faithfull. Post-heroin, mid-comeback Marianne, with white blonde hair in whispery bangs, a softening chin, and eyes rimmed with thick, nostalgic kohl, eyes that widen and protrude just enough to remind us of their secret, spherical nature, their hidden roundness. She is aware of the camera and her own implications, speaking with firm intention. In her middle age, Dolours Price seems like she might have once been a star, haloed by the peeling aura of past charismas, but also like she might be somebody’s mum, on a mission at the supermarket, but also like she’s known hell, the bottom of it, and is here to tell you what she knows. There’s something about her that is unearthly, liturgical, which is not to say, necessarily virtuous.

In her small, nice-enough living room, Dolours Price narrates for journalist Ed Maloney how she became a militant volunteer for the Provisional I.R.A. during the Troubles in Northern Ireland, how she planned and pulled off the 1973 Old Bailey bombings with her sister, Marian, how they endured their subsequent incarceration and hunger strike. There are blinks and pauses. She steels herself before her own life.

It was agreed that this oral history, which included confessions of brutal violence by Delours and other I.R.A. members, would be sealed away until everyone participating and, importantly, everyone mentioned by name were dead. Most famously, perhaps, she talks about the murder and “disappearing” of a widow and mother of ten, Jean McConville, which is the subject of the 2019 bestselling book Say Nothing: A True Story of Murder and Memory in Northern Ireland, by New Yorker writer Patrick Radden Keefe.

The book also follows how that agreement of posthumous release was distorted and ultimately broken; although Dolours Price died of an overdose at 61 in 2013, the tapes were seized that same year by the Police Service of Northern Ireland and used in an effort to prosecute the surviving I.R.A. members named in her account. The 2018 documentary, I, Dolours, intersplices the original tapes of Price with grim, awkward reenactments (notably, a montage of the main actress making herself vomit faded over historical footage of Margaret Thatcher quoting St Francis of Assisi). It is available for rent on Amazon.

The long, pretty face of a now-defunct revolution expands to fill my laptop screen. “We had the great honor of having had three generations of women in my family spend time in Armagh Gaol,” Dolours intones, with ritual solemnity. Sometimes her tone curdles and becomes ironic, rueful, brimming on the lip of a joke, but this isn’t one of those moments. This is honor meant in the most maternal of ways, cinched and metallic. Her grandmother, her mother, herself and her sister, as well as multiple aunts, were all incarcerated at different times in the notorious women’s prison for their involvement in the Republican cause. It’s hard to imagine now. Almost 40 years after the last Price daughter was freed, the 19th-century prison is currently under construction to become a four-star hotel.

The Troubles was a strange war. It has been described as civil, sectarian, low-level, guerrilla, religious, nationalist, and anti-colonial, all at once. The opposing sides were splintered, zealous, tautological, and clandestine, and their surreal methods of warfare mirrored the parties involved. The chain of responsibility is almost impossible to parse out, either historically or ethically, and I certainly cannot attempt it here. We are left with the rippling afterlives of such indeterminate histories, the frothy, limpid edge. The United States—despite its ambivalent preoccupation with the starched scandals of the English Royal family and English reality TV—mostly ignores the inner workings of the United Kingdom. But certain paroxysms of upheaval draw global attention: the Troubles, the Spice Girls, the death of Princess Diana, Brexit.

Under the shadow of the latter, the Troubles have newly re-entered the American popular imagination, through Keefe’s book Say Nothing, Anna Burns’ virtuosic novel, Milkman, which won the 2018 Booker prize and was deservedly celebrated by American critics, and the popular TV show Derry Girls, which amassed a huge American audience through Netflix, despite being watched largely with subtitles to decode the Ulster accents. All of these works centralize the “woman’s story” of the Troubles, a period previously dominated by the iconography of the balaclava-clad, ArmaLite-wielding, paramilitary soldier, perpetually anonymous yet implicitly understood to be a man.

When Dolours Price first pledged her allegiance to the Provisional I.R.A., she said she wanted any job “but rolling bandages,” knowing the group had strict gender hierarchies in leadership and assignment. They led her into a small room with a pile of discarded bullets and a ball of steel wool and told her to clean them. The figure of the militant Leftist woman—young, beautiful, and armed—lends itself to easy glamorization and simultaneous vilification, a tabloid’s dream. After Marian (19) and Dolours (22) were caught and imprisoned for the London bombing, images circulated of the two sisters beaming from behind bars, rosy-cheeked doubles sliced by bright metal. They look relaxed and pleased. The two were nicknamed “The Sisters of Terror,” and connected in the media to the “diverse aims of Che Guevara, the Black Panthers, and the Palestinian guerrillas,” (specifically Leila Khaled, the Palestinian hijacker); newspapers announced that “the legend that women are passive, peace-loving creatures who want only to stay at home and look after children has been finally exploded in a thunder of bombs and bullets.”

While Dolours Price’s commitment to armed struggle was inflected and upheld by her experience as a woman, particularly the literal sisterhood that composed her family’s radicalism, her actions were not associated with “feminism” as such until the general public received and aestheticized them. But this was 1973, squarely in between the UK’s Equal Pay Act of 1970 and the Sex Discrimination Act of 1975. This was still a moment where a large-scale, militant feminist revolution seemed somewhat possible, at least in the chatty nightmares of newspaper men or the wild dreams of gathered evenings. All revolutionary aims and activity seemed connected, clinking along the same shining thread, like beads on a necklace. It’s hard to imagine now.

*

When I was around 16, in my junior year of high school in Los Angeles, my history teacher assigned a semester-long research project of any 20th-century political event, our choice. The impossible range of this assignment confirmed my suspicions that absolutely nothing you do in high school mattered. I opted to write mine on the I.R.A. hunger striker Bobby Sands, who died in 1981, along with nine other hunger strikers, after 66 days of starvation in Long Kesh prison. During his strike, he campaigned and won a seat as Member of the British Parliament, but died only a month later, before his term began. His surreal achievement and brutal death drew great support for the I.R.A.—of course, letting an MP starve to death in prison had very different optics than letting the unelected population do so—causing the British government to rush through a law that stopped anyone serving a jail term of a year or more from running for public office in the U.K., fearful of a democratic coup by emboldened prisoners. The law still stands.

Besides a dazed, burgeoning leftism, I can’t remember how I initially justified this choice of topic. However, in retrospect, my unconscious motivations seem clunky and transparent. In the plush micro-universe of my West L.A. girls’ school in 2008, the inverse of 1980s Belfast, everyone around me refused to eat. It was an activity of mostly mimicry and companionship, dizzy trauma-bonding over twinkling Blogspots and tipped out lunchboxes. As classmates started being hospitalized, I became increasingly fascinated by their dedication to this unspeakable cause. I think I actually came across the germinal concept of a political hunger strike on pink pro-ana message boards, sandwiched between pictures of Mary-Kate Olsen smoking. I was an impetuous, often sullen student, just returning to school after a major surgery, but I worked for months on my essay, reading everything I could find. I had certain blind spots; I remember my history teacher’s red note in the margins: “Shouldn’t you mention terrorism?????”

When Dolours and Marian began their hunger strike, they each faced a life sentence, alongside six other (all male) I.R.A. members, for the two car bombs that exploded in front of the Old Bailey Courthouse and the Ministry of Agriculture in London on March 8th, 1973. This was a controversial ruling, as the violent intent of the bombings was debatable: the I.R.A. had called in the locations and descriptions of four cars, loaded with explosives, but due to a “miscommunication within the police department,” two were not defused in time.

It was argued that if the London police had been more capable, the surrounding areas would have been sufficiently evacuated. However, as it was, around two hundred people were injured, the property damage was extensive, and one witness died of a heart attack (perhaps caused by the shock, but not a direct result of the bombs themselves). The group asserted that the point was not to kill anyone, only to bring the environment of Northern Ireland, where car bombs had become an almost daily occurrence, back to its colonial root.

It was the first of many bombs planted on English soil, and the next year, over 30 English residents were killed by I.R.A. attacks. Regardless of intent, the chaos that had been previously barricaded within the tiny landmass of Northern Ireland rushing into the calm, carpeted living room of England itself. It was hard for the public to believe that two girls, barely grown, had picked the lock. At the trial, the sisters beamed, giggled, and looked bored. Batting unbothered eyelashes, they were the most terrifying thing in the world: teenage girls secure in the knowledge that they are cooler than you. Reporters commented on their infinite supply of stylish outfits and bad attitudes. After they were sentenced, Marian stood and shouted to the crowd, “I consider myself a prisoner of war!,” a rare example of teenage melodrama aligning with historical fact.

They were moved into Brixton Prison, a high security all-male facility in South London, due to the I.R.A.’s very successful track record of flamboyant prison breaks. Dolours and Marian had already started hunger striking before their arrival. Consistent with Marian’s far-flung cries, their demands were to be re-patriated to Northern Ireland and re-classified as political prisoners. This status carried huge symbolic weight, but it also afforded you certain rights, like wearing your own clothes and not having to perform forced prison labor.

Sequestered to their cells for their own safety, the sisters took nothing but water. Hunger striking was a known historical tactic of Irish Republicans, evoking the hundreds of imprisoned strikers of recent generations—a legendary Republican writer and politician, Terence MacSwiney, had starved to death in the very same Brixton Prison fifty years earlier—as well as the Great Famine of the nineteenth century which Republicans blamed on British profiteering and colonialism. Like armed struggle, hunger was a family inheritance. During the strike, Dolours wrote to a friend that, if they died, “we’ll be the first women, I think, and are very proud to be so.”

A note about sisters: Dolours and Marian’s mother, Chrissie, had five sisters, all of whom were members of Cumann na mBan, the women’s branch of the I.R.A., in the 1930s. Aunt Bridie, an active volunteer, was assigned to help with a transfer of hidden explosives to a new hiding place. When her male I.R.A. counterpart never appeared, she reached to lift the package herself and it exploded. Her hands were blown off, and her face seriously disfigured, permanently blinding her. With no hands and no eyes, she became “a living martyr” at 27, fully dependent on her family. One of Dolours and Marian’s earliest jobs as children was going to Aunt Bridie’s room upstairs, lighting a cigarette, putting it to her mouth, staying quiet and holding it while she inhaled, exhaled, inhaled, exhaled. Pack a day habit. What more can one say about “care” or “struggle”? The words pale and disperse, pluming into shadow.

*

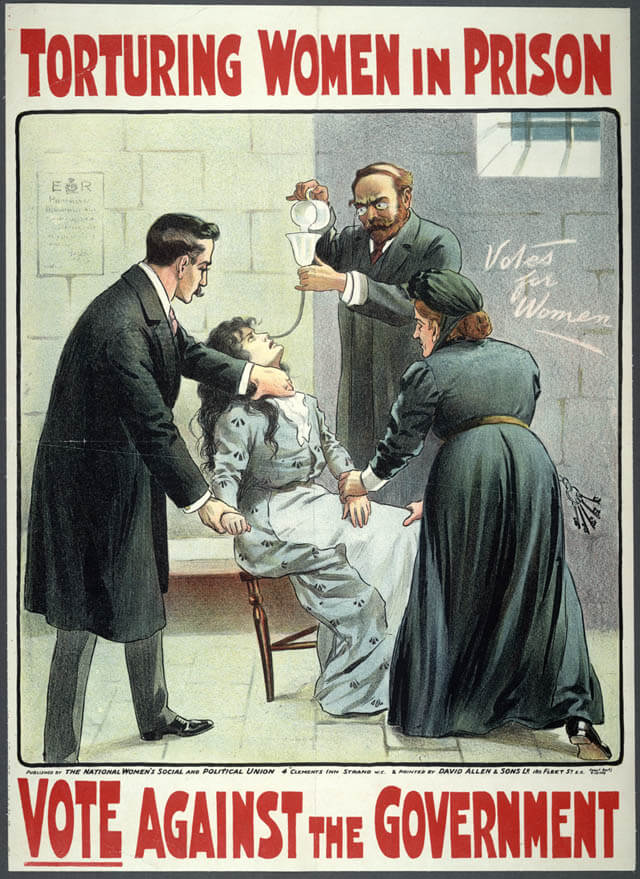

In Ian Miller’s book, A History of Force Feeding: Hunger Strikes, Prisons, and Medical Ethics 1909-1974, the historian opens with a letter from the British Medical Association to President Obama in 2013, protesting the use of force-feeding on hunger-striking prisoners held in Guantanamo Bay. Despite its clear disavowal of the practice, the letter expresses a grave sympathy for the prison doctors who must decide whether to let a self-starving prisoner die, or to intervene in life-saving but potentially torturous ways, violating the prisoner’s consent and agency. This core ethical conflict has been repeated and renegotiated in the United Kingdom ever since force-feeding moved from European mental asylums, where it was invented and normalized in the 19th century, into 20th-century prisons, to suppress the hunger strikes of British suffragettes.

Forcing care upon the “mad” was socially acceptable, as it remains, but in 1909, a group of healthy, often respected, highly publicized and otherwise sane-seeming women were systematically getting themselves arrested, starving themselves, and pushing the state into an ideological corner: should they let them die, let them go, or forcibly keep them alive behind bars? Letting them have the vote, needless to say, was not considered to be an option. Prison doctors tied the incarcerated women down, pushed thick rubber tubing down their throat, into their stomach, and poured in mixtures of eggs and milk, frequently causing permanent internal injury.

The suffragettes published horrifying accounts of these “artificial feedings” in their propaganda newspaper, Votes for Women, often making allusions and parallels to sexual assault, which ignited massive public debate. The uproar reached an apex when the formerly incarcerated Mary Leigh sued the British Home Secretary, and the prison medical officer who had performed the first procedures, for unlawful assault in the 1909 case Leigh v. Gladstone. The courts eventually ruled the practice curative and beneficial, setting a legal precedent for the force feeding of Dolours and Marian, 64 years later.

It took 208 days of starvation, with force feedings every day for 180 days, sometimes twice a day, before the Price sisters won the right to return to Armagh Gaol. As their bodies weakened, so were they transmuted into symbols. Previously considered criminally insane or tragically misguided by the general public, they became iconic victims of state torture, linked with the suffragettes and an abstracted Irish mythos, serene in the face of injustice. Privately, there was only long, ragged suffering. With the only nutrients available by force, they often only ingested their own vomit, forced up and then back down by the tubes. According to visitor accounts, their hair turned white and their teeth loosened, whole bodies frozen in slow motion decay.

But their political commitment never wavered. Even their father, interviewed on television about his daughters’ perpetually imminent demise, answered almost casually, “Well, at the moment, they’re very weak, but in spirit and mentally, they are very alert, and I suppose, happy in their way.” The sisters themselves wrote, from prison, “[The doctors] have the training to counter illness, psychiatric illness… But how can they fight idealism? As far as we are concerned, our idealism is incurable, which from a medical point of view is frustrating for a dedicated doctor.” The force-feedings only ended when the sisters discovered a way to struggle that made it medically unsafe to insert the stomach tube, and their doctors refused to be implicated in the inevitable harm.

I’ve started calling them “the sisters.” They started out distinct, wild with their own specificity. When the force-feedings stopped and they were allowed to lose weight, they were moved to one cell, as if the decreasing size of their bodies necessitated less space to live in. They lay in twin beds, facing each other, fading. Later, Dolours says, with light frustration, she and Marian “were always lumped together, as if we were some kind of Siamese twins.” Later than later, she says, in her new solemnity—her newfound, ancient solemnity— “When we were separated, I was lost. I was lost without her.” I can’t help but think that, in part, this is a story about sisterhood: its ideals, its horrors.

It’s unclear, still, exactly why England capitulated to the Price sisters’ demands. Pressure mounted, and at a key juncture, another I.R.A. hunger striker in a different English prison, unrelated to bombings, died of a force-feeding gone wrong. The sisters, newly political prisoners and local heroes, were sent back home, if Armagh Gaol could be considered as such. The strike ended in 1975. (It would, in fact, begin the end of force-feeding in all British prisons, and future Northern Irish hunger strikers were allowed to starve until they died, a double-edged achievement). After returning to Northern Ireland, Dolours and Marian were thankfully embedded in a community of likeminded women prisoners who knew the Prices and shared their life project. But as the years of a life sentence gathered and knotted around them, and the I.R.A. continued their campaign of violence in an increasingly ‘outside’ world, the sisters drifted from the cause. Honor was not the same as freedom. And, without reason or demand, quietly amongst themselves, Dolours and Marian stopped eating again.

*

In Anna Burns’ third novel about the Troubles, Milkman, published in 2018, the protagonist is only named Middle Sister. We live in her head the entire time, where there’s no need for a name, only a multi-pronged relationality. In Burns’ first novel about the Troubles, No Bones, published in 2001, the protagonist is named Amelia and is also a middle sister, but she slips between third and first person, cleaved into objecthood and steeped in chaos. No Bones is the running start to a style that later becomes a body-bending high jump in Milkman, a book that soars, suspended in blue.

It is all heavy breath, gathering speed, stinging light. Stuck in the sadomasochistic tangle of an imploding family, Amelia is white-knuckling it through her adolescence, which happens to coincide with a war. Politics are everywhere and nowhere. She introduces herself: “This sister was called Amelia, she was seventeen, she never ate any food, suffered constant tummy aches, didn’t understand why and was outrageously, sexually thin. She came in the door with that arm-swinging vigor all six-stone hunger-strikers are very keen on…” In a different chapter, Amelia observes, “It seemed the first rebellion was to refuse food. Well, I was already doing that, had been for over three years and all for a reason that was inner, top secret, and to do with my own soul.”

All the girls around Amelia refuse to eat, including Amelia. But the narrator never lingers on these atmospheric pathologies. Anorexia, like this week’s car bomb, is only another daily consequence of a previous consequence, set against a long line of consequences, with no discernible origin. The primordial motive of everyone’s banal habits implies that at some point, someone, somewhere, must have made an un-inherited decision, initiated a cause for all these damned effects. Someone who must have lived a life, a life without the towering “after” in front of it. Was there ever a girl outside of history? Or do the two categories rely on each other, loosely interlocked underneath the school desk of meaning, pinky-promised?

A life sentence does metaphysical violence to a body, by making the time stretching out in front of a person as heavy and calcified as the time stretching out behind them. The past and future might become two flattened, facing reflections—dying sisters in twin beds, staring into the other’s stare. Food, and its warm, crackling promise of more time on the planet, becomes the tether between these two weights, what was and what could be. Dolours explains that, in order to wage a successful hunger strike, you have “to convince your mind that food is bad—to have food, to take food, to eat food is failure, is defeat, is wrong… We both ended up with very distorted notions of the function of food, which resulted in us both being anorexic and not wanting to eat.”

An anorexic ex-hunger-striker seems at first like a categorical tautology. The differences between the two behaviors (self-starving vs. self-starving) confirm that the meaning of a symptom is not determined by the symptom itself, but by its reception and context. Our illnesses are always social, even in enforced isolation, possibly the most socially determined of places. They must be legible, they must be read, and they must be interpreted, in order to function. For all the debate, furor, and archive that piled up around the Price sisters as they were hunger striking, there is surprisingly little tracking the progress of their following years of starvation. Records show that, as other I.R.A. affiliated women prisoners participated in a solidarity dirty protest with the Long Kesh men’s prison, eating disorders became prevalent, and several women died. Dolours and Marian refused to join the protest, but also refused to eat.

The jump between their triumphant success to this new, unclassifiable outcome is abrupt: On April 30, 1980, Marian was released from jail to a Belfast hospital, close to death. On May 1, she checked herself out, a free woman. Dolours remained in prison another year until 1981, when she too would be released on medical grounds, admitted into emergency treatment, and ultimately pardoned. Was this another successful strike? Strangely, Dolours was released by the British government two weeks before Bobby Sands died, further complicating the legibility of either’s behavior. If hunger strikers were force-fed, anorexics were let out, and both sometimes left to die, the significance of protest blurs, halves, and merges. Margaret Thatcher sat back, watching.

This was supposed to be an essay about the long, unexpected afterlives of violent conflict, particularly the echoes of past Leftist militancy through our notably un-militant present moment, particularly in the U.K. and the United States. Dolours Price is only four years older than my mother, and her two children are my generational peers. It was supposed to be about her life as an ex-terrorist with an eating disorder, becoming a mother in the 1990s as Northern Ireland transformed. There was supposed to be an argument in there about private pathology and public protest, how we’ve all leaned into the former as the latter became more surveilled and criminalized. How we often starve ourselves, but rarely hunger strike. I was wrapped up in all the ex-identities. How to survive having become a historical object. The state of once having had a purpose. Maybe that’s because I feel like I was born, fresh and new, into that condition of once-having, the child of a whole century’s disillusionment. I was supposed to start at the end, but I couldn’t get there in time.

In the tapes of Dolours Price, she chooses her words carefully. At the time of recording, she had just been released from psychiatric care for alcoholism and post-traumatic stress. She was in and out of hospitals and institutions for much of her late adult life. But on the tapes, she is the opposite of chaotic, preternaturally sober. When discussing her crimes, she always speaks in “would have been’s.” We would have been ordered to drive him across the border, you would have needed to rob a bank, I would have been in charge of executing my friend.

At its height, the I.R.A. relied on the precision of its language—the slippery ways one can sidestep confession. They were Catholics, after all, trained in the recital of sins. The perfect continuous conditional tense: something that might have happened in the past. The unfulfilled result of the action in the if-clause, often counter-factual, expressing this result as a continuous, perpetually ongoing action. But, 30 years later, Dolours’ perfect, continuous, conditional sentences do not sound like they are meant to avoid guilt. They sound only like a method of prayer.