Music for Television

Sasha Frere-Jones

December 1, 2020

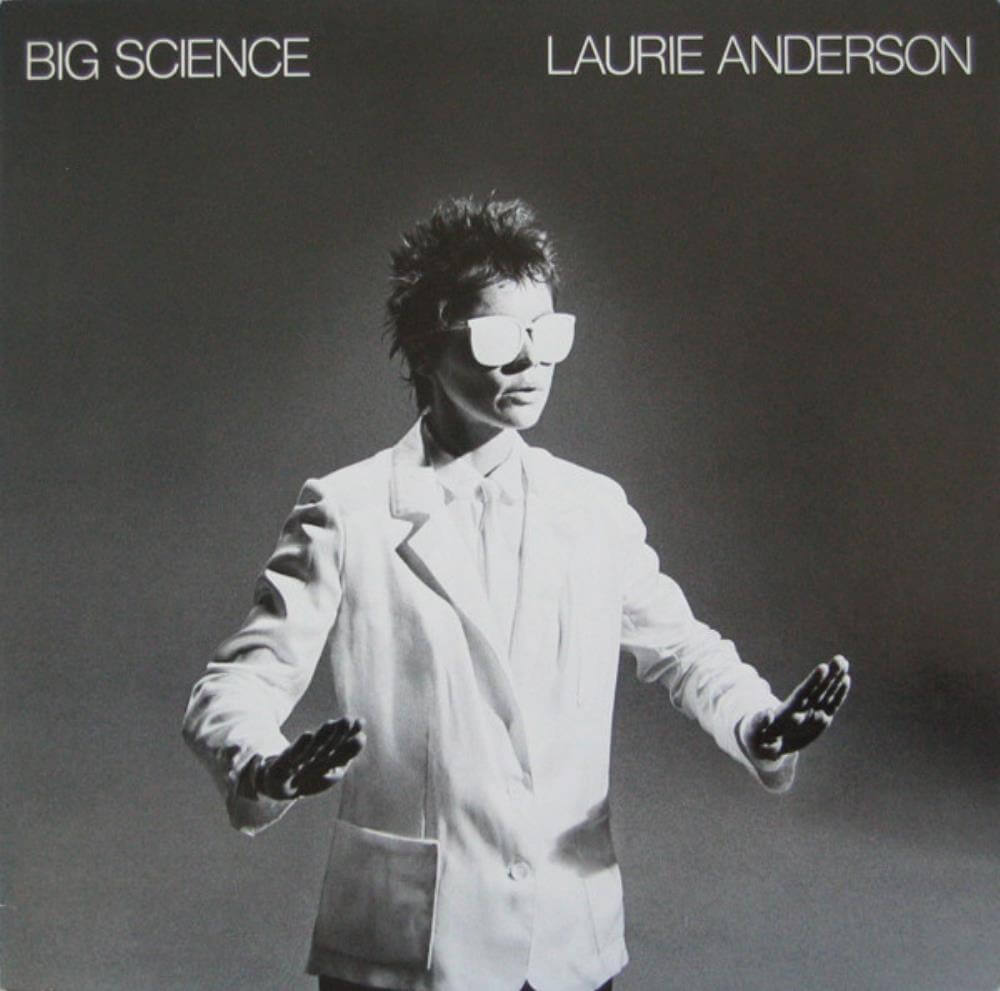

In 1982, Laurie Anderson released an album called Big Science. On the first track, “From the Air,” Anderson plays a captain going into a crash landing. A breathy two-bar melody has been fed into an effects unit and loops behind her low and even speech as she begins our descent.

“Good evening. This is your Captain. We are about to attempt a crash landing.” Then, she plays a game of Simon Says, maybe to distract the passengers.

“Your Captain says: Put your head on your knees.”

She levels with us.

“We’re going down. We’re all going down, together.”

Sometimes you gotta give it to them straight.

“This is gonna be some day. Stand by.”

I received an email on August 1st of this year. The subject header was “Really bad news.” My ex-wife, the mother of my two boys, is very sick. The news was worse than bad but it was straight. I biked down and around the lower edge of Manhattan on my bike and listened to “From the Air” four times. I’m rarely agitated in that neighborhood. Sometimes, I sit on a bench near the water and hear a voice, right there above my head.

“This is the time. And this is the record of the time.”

Big Science comforts me. Following the discontinuous streets in the Financial District and hearing Laurie Anderson’s voice—bureaucratic, vernacular, casual, elected, demented—makes me feel that peaceful stasis is something you can have. Anderson places me securely in the 21st century by making me think of the 20th. More specifically, Laurie Anderson reminds me of Laurie Anderson and every other 20th century figure who disabused people of their worst illusions and copped to their own. They gave it to you straight.

“There is no pilot. You are not alone. Stand by.”

That voice is identifiable but vague. It’s the voice of someone with a job who isn’t a New Yorker. It’s a white person, but not from a place I know. Anderson described this voice in a video from the late ’80s, filmed in her home studio. She called it “a voice of authority, or a kind of shoe salesman or a guy who’s trying to sell you an insurance policy that you probably don’t want or need.” She was talking about a version of her voice put through electronic filters and lowered, but one that still sounds like her. Laurie Anderson’s pauses give her away even when she’s in—

disguise.

Anderson is one of our Midwestern skeptics, our Greek chorus in chinos. These people came to New York to doubt us, to raise their eyebrows and then lull us (or themselves) to sleep. They believed that we might disagree and that being American involved a fairly consistent practice of self-deprecation. These voices were slow, always slower than we were. They found us amusing and told us that if we would tolerate them, they would tolerate us.

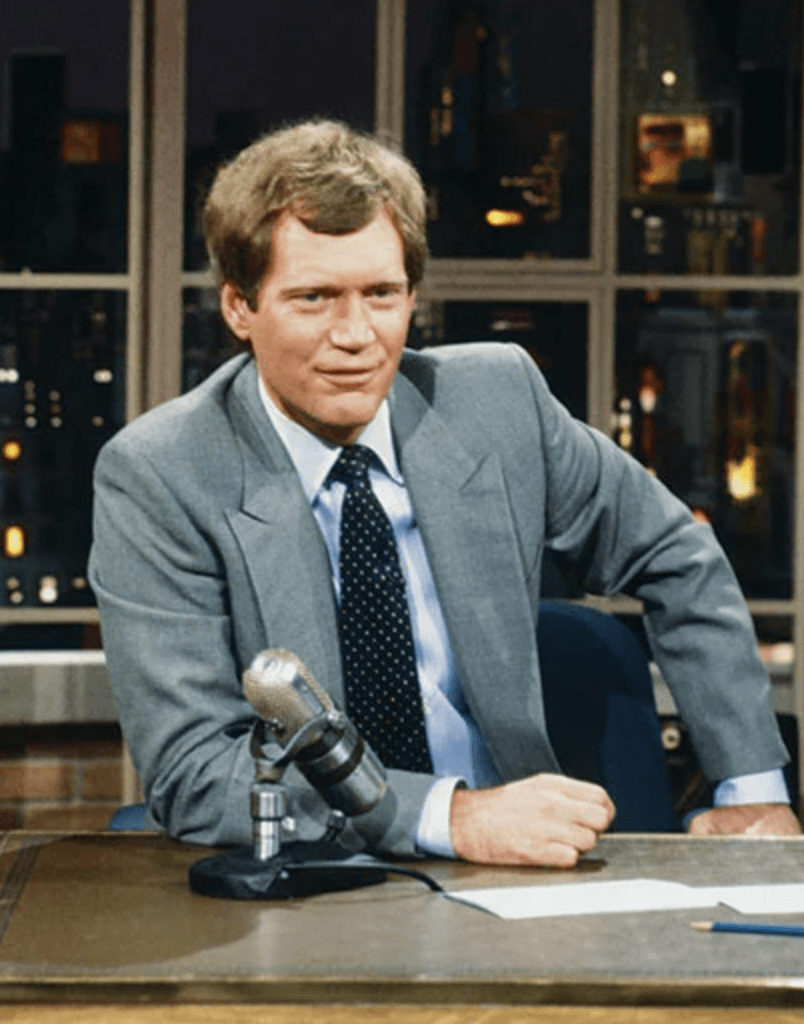

Anderson is from the suburbs of Chicago, Robert Ashley is from Ann Arbor, and David Letterman is from Indianapolis. In their stewardship of the avant-garde and the commercial avant-garde and the odder corners of the mainstream, they extended me a kind of handshake. For the first twenty-odd years of my life, from the ’70s into the ’90s, their voices lulled me into something like acceptance, or maybe a qualified optimism that can double as belief. I didn’t know what it was and I hadn’t thought about where it came from until recently. It is the voice of television, and it is gone.

This was the gray susurration of PBS and all the corduroy dads of the long afternoons: Dick Cavett (from Nebraska), Mike Douglas (from Chicago), and the game show smilers. I grew up with an unearned pride in the New York voice. I loved the hair-splitters of baseball and Lou Reed and the guys on Fulton Street who yelled at me for asking questions about budget sneakers. But these were from a different layer, close to me and not in charge. The people in power, the presidents and TV show hosts and people who played in auditoriums like BAM, they didn’t sound like New Yorkers.

This was the voice of civil disagreement, of late night radio, where a common weirdness was expected. And at this distance, some thirty-odd years later, we can see that radio and television were the same thing at some level—a monophonic voice we could not control.

The American act of migration was in that voice, the voice of a car, in a car, coming to us or leaving us. It was the midnight shift guy who leaves massive blank spaces between his words, pausing even longer than Laurie Anderson, trying to explain Well, the thing is, nobody ever sounded like Lightnin’ Hopkins, not even Lightnin’.

In 1982, all of 15 years old, I saw New York as the center of the physical and moral universe and these people, in their ideas, were on New York’s side, always against America. They were as allergic to American triumphalism as I thought myself to be. America itself was a punchline and it seemed we would be moving on to a different mode under their watch, not cycling back into some kind of jingoistic death mummery where we trot out a Lee Atwater riff from the ’80s as if it were a canonical 18th-century tract. Even a movie star like Robert Redford, from California—he uncovered the CIA inside the CIA in 1976, in Three Days of the Condor, and he ratted out the oil barons. We got ‘em bro!

I asked Mimi Johnson, owner of the Lovely Music label and Robert Ashley’s widow, about these American voices that I was convinced Ashley heard on the radio or on television.

“Well, yes, of course, if anything, it was radio,” Johnson said.

“I’m thinking of Franklin Roosevelt and his radio addresses,” she added. “I mean, like everyone else, Bob would quote ‘I hate war! Eleanor hates war! Even our little dog Fala hates war!’ Bob’s family came up from Tennessee and they were dirt poor, so FDR was certainly of a hugely different social class, but he spoke slowly and dramatically.”

That cadence was submerged, soaked, and tumbled dry for Ashley’s monologue, “The Park,” released in 1978. I found it when I worked at a college radio station in 1985, on the Private Parts LP. Ashley presses the dark green heel of his bottlevoice into your shoulder while Blue Gene Tyranny sparkles on his keyboards and Krishna Bhatt falls like rain on the tabla. Ashley is sort of leading a sort of guided meditation sort of. He seems not to be sleepwalking as much as revealing what it is like to sleep for a long time and wake up in a different place and then tell us about that place before being pulled back.

The voice soothes but the voice is taking careful note of everything around the voice.

“Obedience was impossible for him. At the same time, he was cooperative and indeed solicitous.”

Ashley is describing himself remembering, or remembering himself remembering. He puts himself, or his avatar, in various places, starting with a motel. And then he moves.

“The men are in the park in the small Midwestern town. That is, the benches in the park. We know from what is best that the men are on the bench.”

He orders room service, paid for by “the company.”

“This is a record, I am sitting on a bench next to myself. Inside of me, the words form—‘Come down from the tree and fight like a man.’”

I accept this voice, whether it comes from Bob or Laurie or Dave. I love it whether it comes out of a president I don’t believe in or a woman explaining disaster through a pitch shifter or a talk show host telling me he’s got a really great lineup. I accept this voice.

David Letterman interviewed Grace Jones on his show in 1986. She came out covering her face with a gold mask, a huge and ceremonial thing. She was trying to be playful and avoid being seen but it was television.

“You were late last time, you’re late this time,” Letterman said. “We do this show at 5:30 and it’s five after six now.”

After scolding her, he eased back. She removed the mask and started some coked-out rambling. Letterman asked if her long coiled earrings were Monro-Matic shock absorbers, which was a plausible question. The publicity machine hadn’t yet absorbed all public interactions and people were allowed to have disagreements in front of cameras. There was nothing ideal about human experience in 1986, nothing more just about that world, but representations allowed for tension.

On August 26th, the third night of the 2020 Republican National Convention, Metrograph streamed Laurie Anderson’s 1986 concert film, Home of the Brave, on its website.

After some awkward dancing with her band, Anderson, wearing a baggy white silk suit and a ski mask, her voice pitched down to that salesman register, takes the stage alone and describes binary code. She says “a couple of numbers have been bothering me lately.” Zero and one. There’s a “national obsession” with the number one. She suggests that we “get rid of the value judgments attached to these two numbers, and realize that to be a zero is no better, no worse than to be number one.” Zeroes and ones are “the building blocks of the modern computer age.”

This language of television was a coherent argot of game shows and teachers and flight attendants and politicians and yodeling and it was Robert Ashley turning his uncle Willard into an opera character. Home of the Brave is nothing if not the dialectical motion of television itself, taken onto the stage of an opera house. It is a lingua franca built entirely from bits and pieces of popular culture.

In 2000, Robert Ashley wrote a short account of his life and work for Gisela Gronemeyer and Reinhard Oehlschlägel of MusikTexte. This paragraph is relevant:

“Everybody watches television: news, soap opera, sports, comedy. I thought that if I could ‘inject’ music into that ritual, it would get to the listener in the most direct fashion. It would be there. And some would listen for a few minutes, and others would just change the channel. For those who decided to listen and watch it would be the most intimate contact with music. I would make music for television.”

I came back to Ashley in 1989, right after not graduating college. His relaxed approach to cultural authority felt reassuring. The guy who put out Automatic Writing wouldn’t give a shit about a college degree, right? I worked at a restaurant at the corner of Wooster and Prince called Food, and the dishwasher there lent me a VHS copy of Perfect Lives, Ashley’s 1983 “opera for television in episodes.”

“Bob wanted to make opera for television,” Johnson told me. “Carlota Schoolman, the video director at the Kitchen, wanted to produce a work for television. So began a three-year period of making the video opera.”

“The specific location for the video opera was Galesburg, Illinois, where I grew up and where Bob and I had visited my dad. Standish Park in Galesburg is next to the ‘courthouse of the county.’”

“The Galesburg video footage was made in the summer of 1980, and the soundtracks were worked on. A lot of live performances took place between the fall of 1980 and fall 1982, using the Galesburg footage on TVs as the ‘set.’ In 1983 additional video material was shot in New York City (in our loft, in a church on Sullivan Street, in a supermarket on the Upper West Side). The Channel Four television premiere was April 1984.”

Perfect Lives opens with a new version of “The Park.” Ashley appears as the subject of the lyrics—the man in the hotel room—and as himself, reciting the lyrics. The congas are gone, and Ashley is reciting the words with a lively kind of disjunction, occasionally swinging his hand as if conducting, waving out the stresses of whatever line he’s delivering. There are new piano sounds on top of the language, which sometimes drown out the words, and footage of corn fields and tractors in Galesburg. Ashley is wearing a nice green scarf. It was like I’d found Laurie Anderson’s uncle, who talked as slowly and unpredictably as she did. Perfect Lives was obviously some kind of avant-garde that didn’t care if it was called “avant-garde.” This older, wiser person was going to plop down and gently rib reality until it gave up and went to sleep.

Laurie Anderson only appeared on David Letterman’s show once, in 1984. She performed a song sitting down, pitching with her voice way up with an effects unit and strumming her violin like a guitar. She sang, or spoke, “Walk the Dog.” Afterwards, Letterman seemed confused but not unhappy.

“That was a really interesting performance.”

Laurie smiled and thanked him.

“I’m only asking you because I guess I don’t know about things like this, but how would you describe what you did there? What was that? It was performance art but it wasn’t really a song was it?”

“It was a country and western song.”

“That was a country and western song.” Dave laughed.