On Vacation

Adam O'Fallon Price

February 25, 2020

“Why,” asks the girl at the gift shop register, echoing the question I’ve been asking myself on and off for the last week, “would anyone come here on vacation?”

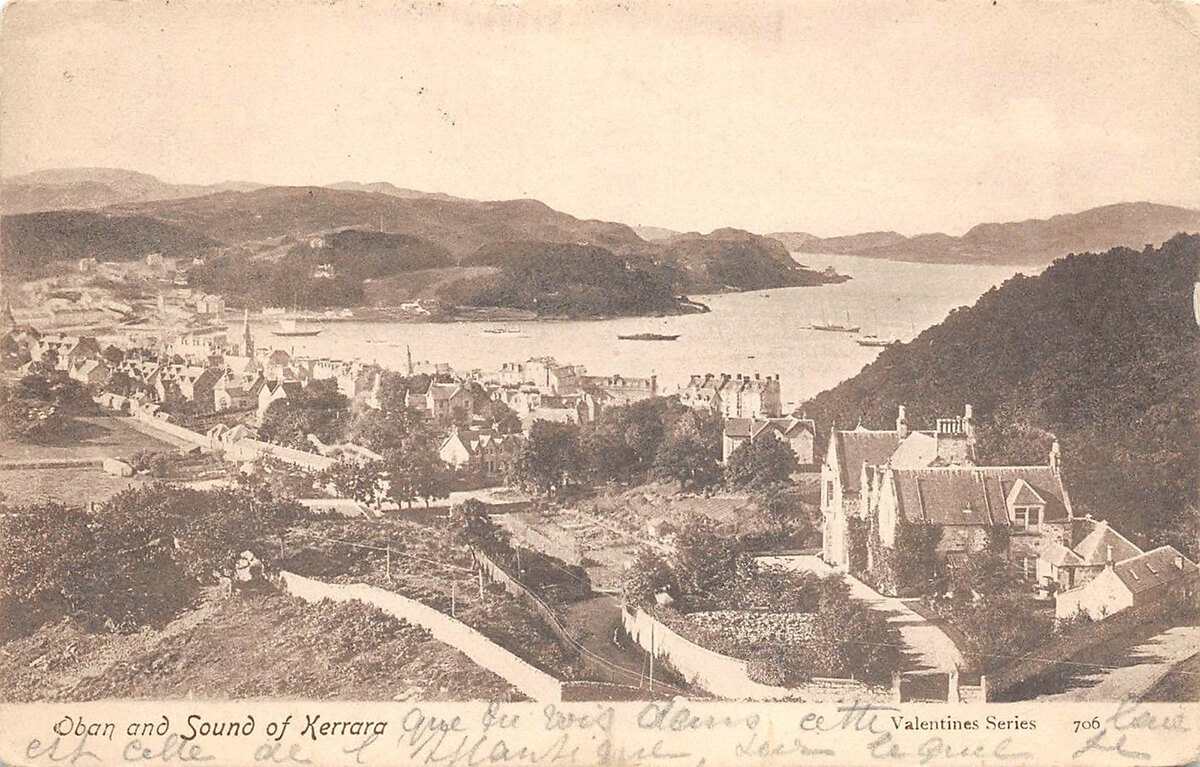

Here is Scotland. More specifically, here is a fishing village called Oban. The gift shop is located just off the main pier, and after days of passing it on our way into town, my wife and I have, at last, dutifully submitted to participating in the local retail economy. We’ve picked out souvenirs to take back for friends and family: a tartan bookmark for my mother, a tea towel for my wife’s sister, a plush stuffed highland cow for our godson. This being Scotland, the place also features an incongruous wall of single-malt whiskies, all marked up about two hundred percent.

The clerk’s name is Abbie. This information could easily be gleaned from her nametag, as well as from her stream of self-referential patter, but to be on the safe side, after imploring every shopper in line to fill out a comment card praising her service, she says it again: it’s Abbie. While waiting, we’ve learned that she is eighteen, that she’s Oban born and bred, and that she’s planning to attend school for the dramatic arts, having finished with her A-Levels. Is there, by the way, any cultural thing more singularly British-sounding than A-Levels?

Abbie greets us with a smile, and when we say hello, she says she loves our accents. Ah loove yir aucksent. That, I say, may be the first time a Scottish person has ever praised an American’s accent.

“Where are you from?”

“North Carolina,” I tell her, with the usual uncertainty of whether people overseas know anything about American geography, despite being reasonably certain they know more about it than most Americans.

Abbie knows America. She goes on to tell us, with stunningly apolitical zeal, how much she loves our country, to enumerate the places she’s been (New York, Los Angeles, Arizona), and finally, with a shake of her head, to wonder why anyone would come here. “I mean,” she says, popping my card in the hand-held reader, “you have fifty different states, like.”

I smile and mumble something and shrug, and, bag of mementos in hand, we hunch back out into the ceaseless rain. I’m obviously not going to mention it to a nice stranger making conversation, but the honest answer to Abbie’s question—although I’m not sure why—is that six months earlier, in a hospice in Nashville, Tennessee, my father died.

*

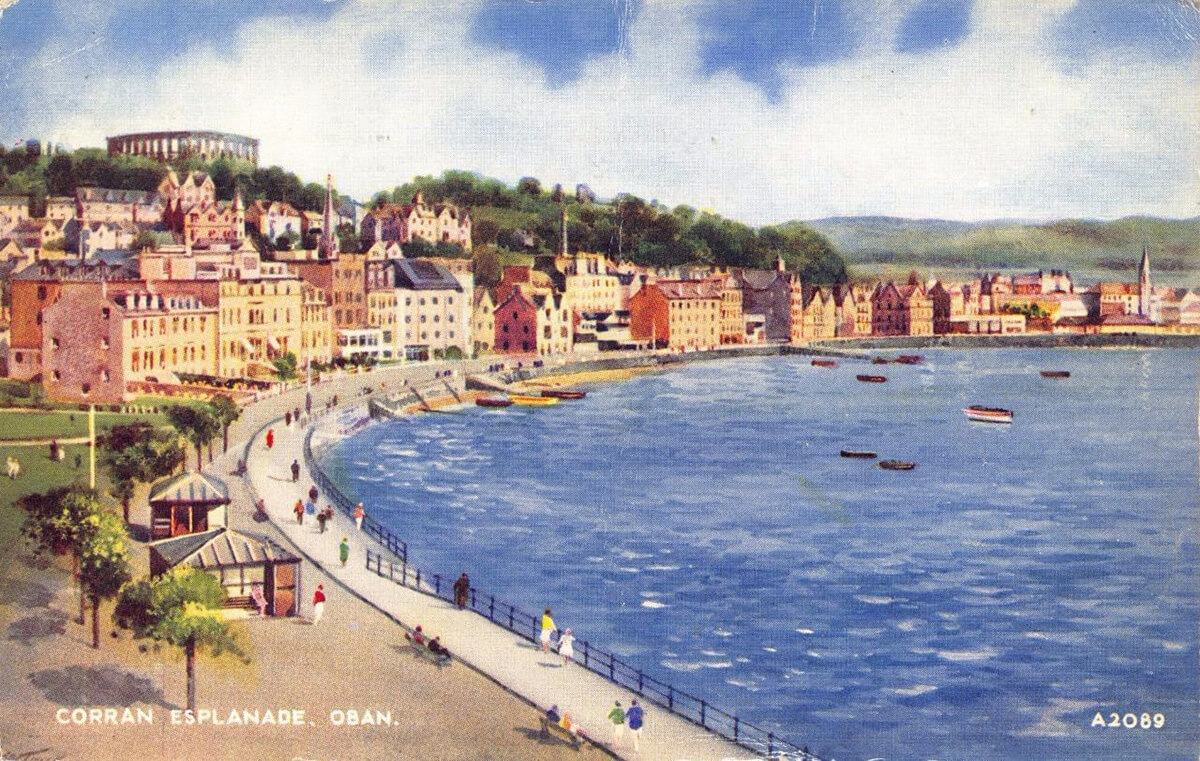

Oban is located on Scotland’s west coast, where the Inner Hebrides meet the Lower Highlands. The window of our Airbnb affords us a spectacular panorama of the harbor—to the far left of the vista is Kerrera Island, and to the right sits Oban City Centre, with its docks and ferries and candy-colored storefronts. McCaig’s Tower, a replica of the Colosseum designed and commissioned by a local banker in 1897, and abandoned half-finished upon his death in 1902, overlooks the town and lends the proceedings a slightly absurd classical grandeur. It is a beautiful place, without question, but it is a strange place to go on vacation, especially if, like my wife and I, you have no Scottish ancestry, no love of golf, no intense fascination with bagpipes or distilleries or fisheries.

The original idea for this vacation had been Madrid, our favorite city. My wife taught English there for an impromptu year after college. I have only been once, for ten days, and have longed to go back ever since. Madrid is, for me, the perfect vacation spot: a great world city that wears its greatness lightly; a schedule-free mecca of art and culture, where the primary local leisure activities are walking, eating, drinking, and sleeping.

We had planned to take the trip between Christmas and Epiphany, when this Catholic city is quiet, when we each had time off and would be surrounded by fewer tourists We’d bought the plane tickets, made our rentals, and begun plotting out our dinner reservations, when, in September, my father had his first stroke.

On the eight-hour drive from North Carolina to Nashville—in desperate need of something non-existential to discuss—we went over our upcoming obligations and trips, though it was far too early and uncertain to adjust any plans. It seemed very likely, in fact, that my father might die in the next day or two. Compounding the stroke, he’d suffered from lymphoma for several years, during which time he’d lost fifty pounds, many teeth, and, for a while, his signature fisherman’s beard, revealing a face that looked disconcertingly like my own.

The year before, he’d also been diagnosed with an unrelated lung tumor and lost the lower third of his left lobe. Factoring in other various pre-melanoma treatments and dental surgeries, he seemed to go under the knife about once a month. Still, he emerged from each operation intact and sticking to a long-standing daily routine that saw him rise at 5:00 AM, listen to sports radio with a tankard of coffee, drive to McDonald’s or Panera for breakfast (he loved fast food breakfast with a deep, inexplicable passion), work on his computer, putter around the house, nap, make an early dinner, and usually stay up too late reading mysteries (it occurs to me, writing this, how perfectly Madrid’s eat, drink, nap, walk, repeat schedule would have suited him). And though I knew he wouldn’t live forever, with each additional ailment and recovery, he seemed increasingly immortal.

His recovery from the September stroke further strengthened that impression. When we arrived, he was completely unconscious, only exhibiting life via the occasional moan or reflexive kick of his unaffected left leg. He’d been agitated upon arrival at the ER, and the doctors had sedated him with doses of Fentanyl and Valium that were incapacitating in their own right. The only doctor willing to speculate ventured a guess that my father might, one day, recover some limited motion, some speech if he was lucky. Two days later, he was sitting up and talking, eating by himself, and exhibiting full cognitive function other than a merciful caesura regarding the stroke itself, during which he’d wandered undressed into the kitchen and made several cheese sandwiches before collapsing.

We left Nashville in a fog of complacent relief and denial. In various iterations, we repeated the mantra: well, looks like the old man dodged one more bullet! Normal life resumed in North Carolina and Tennessee, and we maintained Thanksgiving plans to meet at a rented mountain cabin in Asheville.

It was early November when my mother called to tell us he was back to the hospital, having suffered two seizures. Seizures sounded less dire than a stroke, but when I visited over the long weekend, it became clear that this was a continuation of the original trauma, a deferred worsening. By early December, he’d been moved into a nursing facility with a peg tube in his stomach and the vague, fond hope of partial rehab. By mid-December, he’d landed back in the hospital with more seizures and brain bleeds, and I was back in Nashville helping my mother move him to hospice. I’ll spare the reader, and myself, an account of those last days, other than to say the gaping cave of his mouth is a tunnel into mortality I expect to see for the rest of my life.

Through most of this, a question lingered like a tiny, aggravating pebble inside a shoe: should we cancel our trip to Madrid? Looking back, it seems foolish that we thought we’d be able to go, but at every juncture there was a chance he’d miraculously improve, the way he’d trained us to expect over the last few years. And even if he didn’t improve, we thought he might linger through January and that we’d need the break, something life-affirming. My mother, a staunch proponent of the “we don’t want to be an inconvenience” school of parenting, insisted that we keep our plans.

By the time we moved him to hospice, though, it was clear we had to cancel. Delta provided us travel vouchers, and our Spanish hosts were sympathetic. Then he died. And now here we are, for some reason, in Scotland.

*

I write this sitting in the second floor lounge of the Oban Inn, next to a group of German tourists. I don’t speak German, but I’m almost certain they are discussing Alicia Keys. Either that, or there is a German word that sounds exactly like “Alicia Keys.” On the TV, Sky News alternates between highlights of regional Scottish football matches and strange political debate segments in front of green screens. Outside, it is still raining. It is always still raining. The area is completely gorgeous, but much of the town itself is dowdy, like an elderly relative’s unused sitting room. The trip has been fascinating so far, yet permeated with a constant sense of mild incredulity. Haggis, Irn-Bru, kilts, bacon-butties, the Highland Games: as the checkout girl said, why here?

After my father died, I found myself incapable of rebooking the trip we’d been planning before. It felt wrong, like pretending what had happened had been a minor inconvenience, since corrected. But we had to spend the vouchers within six months, or we’d lose them. I don’t remember when, exactly, Scotland first came up, but I remember it feeling right in its perfect randomness. A couple of Scotland-loving friends suggested Oban, we did a little research, and booked the trip.

I order another one of the beers they have on tap, all of which have very interesting names and very interesting labels and very uninteresting flavors. On the telly, the news has moved to coverage of a regional fishing strike. The table wobbles a little as I return, sloshing lager on my computer keyboard. One of the Germans looks over.

“Ja,” he says, “Ja, Alicia Keys.”

*

Why vacations, at all? Why do we go on them? The two obvious reasons correspond with the two main styles of vacation: curiosity and pleasure. Madrid, for example, easily checks both of these boxes: Las Pinturas Negras followed by tapas. But there’s something else, I think. After all, at home you can eat well and relax on days off, and it’s equally true that in most places there’s plenty of cultural interest, however fine-grained, within a short drive.

Vacations interrogate in some deep way, I think, our sense of life’s arbitrariness. Most of who we are comes down to circumstance: our parents’ genetic and financial well-being, or lack thereof; the colleges we happen to get into or not; the friends we randomly make; the love we randomly meet at a party or concert; this or that horrible illness we so far have had the good fortune not to catch. As much as we like to feel we’ve created our lives, we mostly only control what’s on the margins. Otherwise, the basic, foundational facts control us.

On vacation, we imagine ourselves in other places, other lives. One of the great, reflexive pleasures of going on trips is pretending what it would be like to live, to be from, somewhere else. Tourists are ghosts momentarily haunting houses occupied by flesh-and-blood natives. In assuming the role of traveler, we tacitly acknowledge the strange circumstances of our existence, familiar and comfortable purely for the fluke of being our own. It is chastening to realize how easily, with how little thought, we normally accept the non-negotiable terms of our lives.

Sitting beside my father in hospice, I sometimes had this sense. During the two weeks he was there, the room next to us housed four different patients. Each of them was moved in as a distinct person, an individual with a name and a history and a million little idiosyncrasies; each of them was moved out indistinguishable from all the others, covered by a sheet. What a grievous personal insult death is, and yet how impersonal and banal in nature, so strange in the way it fiercely combines particularity and universality. It was my father dying in that room—my father, who’d married my mother, who’d had me. But when the time came, the crying in our room sounded an awful lot like the crying we’d heard next door, and the body under that sheet could have been anyone.

*

On our last day in Oban, my wife and I take the ferry to Kerrera, a tiny island that sits across the harbor in front of the Isle of Mull. Kerrera Island is mostly unpopulated, save for a few hermits and land preservation workers. It’s a five-hour hike around the south end, a place barely touched by human existence other than the hikers like us who come here to get away from Oban, a place where you could hardly already be more away from everything. Flocks of sheep marked with Day-Glo orange and electric blue dye suggest the presence of shepherds, but they are nowhere to be seen. It is my wife and me, and the sheep, and the alien crows, and the waves, and the weather.

Halfway through, we encounter a Tolkienesque tea house run by eco-hippies. A nice bearded guy informs me they open in thirty minutes, and I find it somewhat amusing that they keep to a schedule around here. He says in the interim we might want to check out the castle.

The castle?

He points vaguely behind us. “You’ll find it.”

Twenty minutes later, having followed a muddy rut up a vertiginous cliff side populated by bounding lambs and a herd of cattle with bangs like teenage surfers, we do find it: a castle. A small one, yes, but a castle—jutting out of the emerald green above us, framed by ancient rocks and a thick gray sky. It feels like we’ve walked into a Led Zeppelin album cover. Only in Scotland is the person-to-castle ratio so nearly even that you might stumble across one on a hike, untended and non-monetized.

The castle might be better described as a giant turret, several stories high, with newer wooden stairs that allow access to the top. We climb into a circular room with a fireplace, little nooks for sleeping, and tiny holes in the stonework through which arrows could be launched. A plaque describes the rough loneliness of life in this outpost, though it hardly needs describing. It’s remote now—how remote must it have felt five centuries earlier? The edge of the world, the legend Here Be Dragons floating in the air just outside your window. You could imagine, couldn’t help but imagine, really, the men sitting here, huddled in their animal skins, so completely different from us yet so exactly the same, equally marooned in the circumstances of their lives. And how easily we might have been them, too, sitting in Gylen Castle; how easily we might have been no one at all.

Approaching middle age, you realize that at the ambitious rate of a big trip every few years, you have about ten to fifteen left. Every vacation you’re taking is a vacation you’re not taking. Are you really more interested in Prague than Vienna? Contra Billy Joel, Vienna might not wait for you. The all-you-can-eat buffet of your twenties becomes an increasingly limited menu by your forties—options, it turns out, are not unlimited. Half aware of this, you make your fumbling best guesses about destination, lodging, places to go and things to see. At a great outlay of time and money, you trundle off, enduring airports and airplanes and airplane passengers in order to get away.

Getting away is not only a trite construction, but a false one. The clichés are true: there is no getting away from yourself, and no matter where you go, there you are. For many people, myself included, the awareness of this fact can somewhat dull the appeal of travel. I carry my dumb thoughts, habits, anxieties, and obsessions with me like a clutch of unwieldy luggage.

And yet, this is not to say that travel is pointless. Getting thousands of miles away from home grants the distance necessary to see home clearly, to see how provisional the idea of home really is. Returning brings not only relief, but mild shock at how it’s all gone on in your absence. Likewise, the entire world somehow manages to exist without your presence or consent. The rituals of vacation—helplessly and reflexively taking photos (seven hundred from this trip), putting those photos on social media, obediently seeing sights and buying souvenirs—articulate and particularize the vastness of Everything, turning it into something that can be bought and put on a shelf. It is a large world, after all. Enormous, terrifyingly so.

*

Bolstered by Earl Grey and lemon rhubarb cake at the tea house, my wife and I resume our trek around the south end of the island, which looks out on the Isle of Mull. Here, it is less greenly lush, rockier and desolate. We pause on a gravelly spit of land, the wind picking up the scent of nearby gorse—the ubiquitous yellow vegetation that our hosts have told us smells like pineapple, and that, improbably, does. Sheep dot a distant hill, clustering in pairs. We take it all in, or try to. We take a selfie.

It is so unlikely to be here. But then, it is so unlikely to be anywhere. It is beautiful and I miss William Price, a man who could have been anyone’s father, but who was mine.