Pyongyang Elegance: Notes on Communism

Amalia Ulman

February 12, 2018

Now that the smell of Pyongyang has started to fade I feel the urge to write about it. As much as I look at the photographs or watch the videos that I took, I have a hard time remembering the tone of the morning light filtering into my room, or the exact pitch of the 7:00am workers’ wake up siren. I watch a YouTube video titled “Morning in Pyongyang, North Korea. Very Eerie.” That’s the word. Eerie was my time in the DPRK.

I have a strange relationship with the DPRK. Many times I’ve been asked why I visited. Many have called it a project, as in “art project,” that ambiguous and annoying combination of words. Was I trying to exploit this bizarre country? No, I doubt it. Though it is hard to ignore history. Why did I ever get on that plane? Why was I ever interested? I tend to make work about and become attracted to things that I find either unsettling, terrifying, or unpleasant. It was out of fear and aversion that I fell in love with the DPRK.

It all started when my mother recommended I watch a Spanish TV documentary on Pyongyang. For the first time, I was exposed to the city’s private spaces—its hairstyles, its mirrored elevators and trinkets. I realized how much it resembled my artworks at the time: a combination between resilience and glitter, extreme poverty and Swarovski crystals.

Then I learned that they welcomed tourists. It isn’t even that difficult to visit, as long as you’re not a journalist. It’s just very expensive. I looked at my bank account and decided that even though it was crazy, I had to make it happen. Instead of googling my zodiac compatibility with my new crush, I obsessed over images of the city, imagining myself in it. I watched videos of the DPRK compulsively before going to bed. Anything that I could find, I’d devour it. I read all the books on the topic that were published in the U.S. Slowly, Pyongyang became the location of all my dreams. It became a backdrop of scenes where all emotions get mingled and confused. There, I’d feel both terrified and calm. Darkness hid behind the pastels. For me Pyongyang was a feeling.

From California to China, I thought of my lover, the lover-city. The three-night layover in the capitalist monster of Beijing only fueled my excitement. Along with my Comme des Garçons and Yamamoto clothes, which I had cut the tags out of so as not to seem like a Japanese sympathizer, I filled my suitcase with fruit because I had been told fresh produce was of value in the communist-dream-gone-wrong. A bunch of apples replaced another one, my computer, which I didn’t dare bring with me and left at the Beijing airport consignment.

Day One

Time stopped. The flight from Beijing is one hour long. That’s what the itinerary and the ticket said. And that’s what mattered because as much as my iPhone told me three hours had passed, time in North Korea is not ruled by Greenwich. It is ruled by the great leader and the great leader is magical, therefore unquestionable. Patience is a virtue, in some places more than others. In the DPRK, patience is a means of survival.

Arriving in Pyongyang, my legs were drained. The previous year, a bus accident left me permanently disabled. I can walk, but not for more than 40 minutes. I sat on the floor despite my fear of garnering attention from officials. Security was surprisingly light. They looked at my book of Gertrude Stein’s poetry, the only thing I had left in my bag, and shrugged. On the other side, an awkward 21-year-old student greeted me with sincere enthusiasm. Amalia, bienvenida a nuestro pais! I had forgotten that my passport is Spanish. His Franco-era politeness only made things more surreal. Here I was in the DPRK, speaking my mother language, with someone who spoke like my grandmother.

The weather was like springtime in Los Angeles but without the smog. I sat in a van with who became my three guards, my three wise kings, mis tres reyes magos: the driver, the guide, and the young translator. Though they all spoke Russian, the DPRK’s unofficial second language. No one spoke Spanish except the student. He burned with curiosity; he’d never met a tourist before. He also seemed nervous, almost uncomfortable, to be sitting so close to a girl. Taking into account the country’s conservatism it was very possible he was a virgin. I could see him trembling but his curiosity overtook his shyness as he began to ask me questions in Spanish. Inside the van, Spanish quickly became a secret code.

The van drove in a long straight line from the airport to the city center. On the roadsides, tall thin lilacs stood in perfect rows, 20 centimeters apart, as if a human hand had lovingly planted one every day for 100 years. Later, it was confirmed to me that, yes, humans had done this, if not as a labor of love, then as forced labor.

First stop was the Arc de Triomphe. Or, as the Virgin translated, Arco Triunfante. I was commanded to have my picture taken in front of it, and to smile, of course, because if I had ever been to Paris, I should be happy to know that the Korean version is bigger.

After that, everything was a repetition of the same script, a mantra. The great leader did great things, the Japanese are evil, the Americans are fat and the Koreans of the South are their puppets. They used words like imperialist pigs, capitalist puppets, disgusting consumerism. It reminded me of my childhood in post-industrial northern Spain, where we endorsed—I’m not really sure why—a similar hatred towards American imperialism. Putos fachas de mierda.

That night, the silence in the crystal tower that was my “luxury” hotel was overwhelming. There was no internet. The tourist TV programming, even CNN, Russia Today and Al Jazeera, seemed censored. To read I only had Tender Buttons and Frank O’Hara’s Lunch Poems, but Modernism didn’t make sense in Pyongyang. I stared at the ceiling with a boredom I haven’t experienced since childhood. I remembered a routine of scarcity and mediocrity, when there was nothing left to do. No fresh cultural input, no news, no urges, no stakes, no goals. Nothing on the radio, maybe a Simpsons rerun on TV.

What is my life about now, now that I’m never bored? I thought of my body in space, in this hotel room, its location in the world, the size of my toes in relation to the universe. A feeling of community and insignificance weighed heavily on my chest: my individualism was of no value anymore.

I’ve been exposed to extreme boredom a few times in my life, all of which I clearly remember. First, as an only child with not many possessions. Then, as a hospitalized woman after all my belongings, and legs, were destroyed. Then of my own volition on a religious retreat. In all of these situations there was a moment when the brain’s productivity peaked in an epiphany of sorts, when I could see my life with perspective, living in the present moment. It feels like dying a little and not minding at all. Or like taking amphetamines for the first time. It is just me and my body and my memories, and no one can take that from me. But a mind with no stimulation dissolves into a pause. How much is too much and how little too little?

In religious retreats, the little information ingested is supposedly of an absolute truthful nature. Someone has the answer, nothing else is needed. Studying the wisdom of someone who knows better is calming. Infantilized, you only need a paternal figure. These answers have to do with eternity, transcendence, and a general indifference to the material world we inhabit only temporarily. But the DPRK’s pseudo-religiousness surprisingly denies the metaphysical. I’m nothing, but not in regards of the infinite. I’m nothing in regards to the giant bronze sculpture, to the monstrous granite replica of an Arc de Triomphe.

An ideology that denies the immaterial, like many inventions of the 20th century, falls flat. Humans are mystical creatures. The words of Kim Jong Un are definitely not a mantra, and after a while, people talk about something else. Whether or not they are allowed.

At some point my trip stopped being about the DPRK and instead became a tour of performativity through body language, accessories, and fashion. Everyone differentiated themselves as much as they could within the sea of standardization. I became a tourist of the underworld, noticing hidden economies and wit. Beneath the dull noise of propaganda were conversations in the realm of the senses. My favorite memories consist of jokes, stares, outfits; variations of voice, posture, hairdos.

Day Two

I woke before my alarm. Needing to spend time by myself, without surveillance, I sat naked in front of the window and stared at the sun. I wasn’t allowed to leave the room, but that room was all I ever needed. The light coming in was one of the most beautiful things I’ve ever seen. The orange hues brought peace and pierced my body with a reminder of independence: the sun is and will forever be free. If I was ever given the choice to recreate any moment of my life, it’d be the intoxification of falling in love, or a sunrise in Pyongyang.

The breakfast cafe was at the top of the tower. Its pink and beige walls and mirrored ceiling called to mind Vienna, or a sex hotel, or an ‘80s cruise ship where the staff outnumbers the guests. I ordered coffee from a waiter who looked like Tony Leung Chiu-Wai and began to fantasize about him. The light was beige and the soundtrack was Chopin. The idea of a having holiday affair wasn’t that delusional, after all. The previous night I had dinner with a group of entrepreneurs from Silicon Valley who boasted about sex with local waitresses.

I’d get Tony’s attention by lifting up my cup and smiling. I was happy that I had an excuse to make him come over. It took five North Korean servings to make up for a regular American coffee cup. Everything was perfect. Food was abundant, everyone was happy and apples were served delicately in silver trays. Tony got comfortable and said he wanted to learn Spanish. He took notes on napkins. It was incredible how he’d memorize everything on the spot. Everyone was eager to learn anything. Their memories made me ashamed of my internet brain. Soon more waiters came over to my table to take notes.

After breakfast, I met my guides in the lobby. I gave the Virgin a peach and he seemed puzzled. He probably wanted a newspaper instead. We jumped inside the van in silence. We didn’t know each other well so everything was superfluous. The itinerary I requested had been modified to visit all of the Great Leader’s landmarks. Everything was propaganda. But who was I to complain? This was a dictatorship.

We started with the Museum of Fine Arts, where a girl waited for us in a corner in the dark and seemed annoyed that she had to turn on the lights and guide us through a room filled with souvenirs, hand-painted posters, and paintings of dogs wearing ribbons. The Virgin would mention the names of these internationally famous artists. He was disappointed I had never heard of them. All had price tags.

After the Museum and the School of Fine Arts, which was mostly groups of women doing ceramics, we went to have lunch at a restaurant for tourists. A flat-screen showed the same footage I had first seen on the plane over: flowers, shiny hammers and sickles, and the very same concert of the all-girl Moranbong Band. Everything looked like a cornucopia. It reminded me of my mother whenever I go back home, because she exhibits fresh produce in trays so I think everything is going fine, precisely because it isn’t. A lot of people say North Korea looks staged. To me, it just looked poor.

There are no restaurants under communist rule, so this one felt contrived. We ate at a huge round table covered in little plates. The dishes seemed Korean, but looking closely they turned out to be Russian, except for the kimchee, to which the Virgin attributed exceptional qualities, such as curing AIDS. There was enough food for ten and we were four. I was told to eat but wasn’t hungry. They seemed resentful. Guides weren’t allowed to eat tourist’s food. I swallowed as much food as possible while trying to ignore the Moranbong Band’s music, or learn to like it. Meanwhile, they drank beer, giggled, and said dirty things about me in Korean. On the way out, we went to a souvenir store. I bought a wooden turtle on skis.

*

A few months earlier, at the Hong Kong airport, after having made a bunch of money from a brand endorsement, I had decided to fulfill one of my working-class teenage dreams. I would buy a brand new pair of Miu Miu shoes at the official store, the silver ones with Swarovski crystal-encrusted heels.

I tried the shoes on, walked around, looked at myself in every mirror, from every angle. The shop assistant told me I looked beautiful and I believed him. In their silver reflection I saw the epitome of luxury. This intoxicating feeling ended when I saw the receipt. I hadn’t converted the HKD into USD correctly, and the shoes were much more expensive than I thought. I felt nauseous thinking of all the single mothers in the world who couldn’t afford to pay their rents; a feeling to which I reacted by swiping the card to then leave in the deepest embarrassment. A rookie mistake, or the result of a life of poverty.

There are restrictions for everything in the DPRK except for the shoes. Women expressed themselves through the height and amount of crystals they could handle. So my style was sincerely appreciated. They adulated me for having a good style, unlike the other tourists, those unfashionable imperialist pigs. For the first time in my life, I was part of the mainstream. I let myself be loved in Pyongyang.

Other tourists thought the DPRK was the most bizarre place they’d ever been, but I understood it. I had also decorated sad apartments with plastic fruits and flowers. I’d worn pale makeup, glitter eyeshadow, parasols and flowery hats, all which seemed to be the official dress code of the women of Pyongyang. For someone like me, whose sexual education came from bondage and movies like Secretary, the city was heaven. The citizens of Pyongyang had a (non-consensual) S&M relationship with the Great Leaders—and I was embarrassingly into it.

When simplicity comes from scarcity there’s little enjoyment in minimalism. Minimalism comes from abundance and the DPRK still is in pre-abundant times. We went to Department Store Nº1 and I was thrilled. I wandered around the aisles looking for stationary and browsed the make-up kiosks filled with lipstick and eyeshadow from different decades, as if in a museum of beauty. I asked about the theatrical makeup everyone was wearing and was introduced to the Koryo beauty line. Koryo like the hotel and the cigarettes. Koryo like every brand in the DPRK. I picked two jars of foundation and while I was paying the lights went off.

We all stood still, quiet. Once again, time didn’t exist: it was a Pyongyang pause. I thought of how in the past I myself had romanticized “English Rose” white skin, trying to be as pale as possible—as if I could be more European than Latin, as if I could be selective with my genes for the sake of a better life in an environment hostile to differences.

The lights came back on. We continued as if nothing had happened, taking our conversations right from where we had left them. There are no electricity cuts in the DPRK. Nothing had happened.

Day Three

The sun was shining and I was PMSing. Since my accident, my leg pain is even worse during my period. Everything hurts. I can’t walk. Usually I stay in bed, but on this particular day we were heading to Mangyongdae, Kim Il-Sung’s birthplace. The Virgin wouldn’t stop talking. I was his first tourist and he couldn’t help but being thrilled, but my politeness from the past two days was gone. “What do people think of my country abroad?” he asked. “That it is a dictatorship ruled by a maniac who lets its people starve to death,” I answered. He shrugged with pride and I felt even worse. We arrived and walked up the hill towards a reconstruction of The Eternal President’s childhood home. Every step was torture. Communist brutality isn’t disabled friendly.

I hated myself and everyone else, but the nature was beautiful and the air fresh. Like every other site, the path was neat, clean and empty. Considered a Revolutionary Site, the Native House includes a Sliding Rock, a Warship Rock, Wrestling Site, Rainbow-Catching Pine, a Study Site, old farming tools and a spring with water we got to drink at the end of our visit. I was told that it was the purest water in the world, also, that it had healing properties. I asked if it cured AIDS. They said it cured everything. I drank and it was indeed the best water I drank in my entire life.

Back in the van, my guides asked why I looked so sad, even though I had just visited such a special place. I told them I was expecting my period. They almost covered their ears with their hands. Irreverent, I kept on talking about it: ovaries, blood, women. But the uncomfortable exchange was distracted by the sight of the Mangyongdae Funfair on our way down. I said I loved funfairs and they said not to worry, that we were headed to one later. After lunch, I managed to cancel a visit to another Great Leader Landmark and went back to the hotel to lay down. They mentioned how lazy foreigners are and how Koreans are genetically superior. I contained my desire to tell them to fuck off and retired to my room.

Unable to sleep, I wandered the hotel. There’s nothing I enjoy more than wandering around, and since the accident, it’s a luxury I enjoy by the second. I visited the shop downstairs. I wanted to buy everything but there was nothing I could afford. Maybe as a protection against empty shelves, all the little Chinese imports that anywhere else in the world cost less than a dollar, here cost over $100. It was a shop that didn’t want to sell. And I loved it.

I met the guides and was taken to the Juche Tower, where we were welcomed by a woman who had taught herself English. My hero. She had a funny accent, wore a pink shiny traditional dress, and instantly became one of my favorite people in Pyongyang. I still watch videos of her posted by tourists on YouTube. We took the elevator to the top, for which we had to pay a little fee. Or I could take the stairs for free, the main guide said, pointing at my legs and laughing.

From there we could see the whole of Pyongyang. The clear skies, the unfinished Ryugyong Hotel, the river, other gigantic sculptures and a park where hundreds of people practiced their synchronized dances for the celebrations of the Day of the Foundation of the Republic. The city itself looked like a poster, as if someone had painted it from above. As it grew dark, we headed to the Kaeson Youth Park.

In the square next to the giant Arc de Triomphe the darkness was interrupted by Christmas lighting, though it was a summer night. Teenagers in school uniforms ate ice cream. A woman met us at the amusement park gate. They were opening the whole park for just me. I felt like a teenager in one of those Sweet Sixteen party TV shows. I was perplexed and terrified by the idea but the Virgin was endearingly overexcited. Because the park was always closed, this was his only chance to go in, which meant I was forced to get on as many rides as possible to make him happy.

He chose our first ride. We sat on it, tightened the seatbelt, and the machine took us upwards. Forty meters above the ground, it flipped us upside down and started spinning. I could see a night version of what I previously had seen from the Juche Tower, though distorted by the speed and nausea. After a few seconds, convinced that I was going to die, I started praying. “This is it,” I thought. “I have no boyfriend, no children, I don’t speak to my father and my mother hates me. If I die now, it won’t be a big deal.”

So when we were lowered to the ground I almost kneeled to kiss the concrete. The Virgin misinterpreted my relief at not dying as wanting more. Sadly, I disappointed him by insisting on rides that didn’t involve gravity, like bumper cars or shooting videogames, in which he didn’t miss one single target, proving that even though he was a nerd, he had impeccable military training.

On our way out, the power went out again. The whole park was dark. I could hear the sound of the crickets and the guides breathing. The darkness was heavy in its immensity. I wondered what would have happened if the shortage had taken place while we were up in the sky, upside down. And then I wondered what will happen if they ever transition into democracy. Having grown up in a post-transition Spain I considered the difficulties of these changes. The Spanish dictatorship lasted forty years; North Korea’s, sixty. Will they open a McDonald’s in the center of Pyongyang and go only on the weekends, wearing their best clothes, just like people did in my town in the 1990s? Seems like a bleak future. A downward spiral just like falling from a ride in a funfair. The lights came on and once again we continued as if nothing had happened. I got my picture taken and I don’t think I’ve ever looked more relieved in a photograph.

Day Four

After another breakfast flirting with Tony, the guides took me to the circus. When we arrived, it wasn’t a circus tent that I saw but a building devoted to acrobatics lined with tour buses. Inside were hundreds of Australian and European tourists. I hadn’t seen so many foreigners since I’d arrived. For the first time Pyongyang wasn’t silent. The Virgin was trying to show me the vitrines exhibiting the numerous international prizes granted to the DPRK circus team but people kept on bumping into us so we decided to move on. Also because I already knew that international just meant Russian.

I was sat in between French men in cargo shorts. It wasn’t hard to understand why the Koreans call westerners capitalist hamburger-eating-pigs. Going to the DPRK is expensive. Only baby boomers with disposable income can afford to visit, and most of them are pale and fat. The show started and it was okay. Some performers tripped a little. If anything it was cute, except when the bears came out, which was just sad.

While daydreaming and falling in love with one of the broad-shouldered female leads, the show ended. I asked a British couple how they felt about the trip. Interesting, they said. Which is for me the most condescending colonialist comment one can possibly make. I stopped interacting with the other tourists.

Because it was my last day, my Tres Reyes Magos decided where we’d go next. So we went to a shooting range. Though it was in the middle of nowhere, the circular building was still crowded. Families brought the children and grandparents. Everyone loved shooting. I wanted to shoot too! My excitement waned when I realized I was surrounded by twenty Korean men with shotguns. “This is it,” I thought to myself again.

Both guides asked me for money to buy bullets. Fearing I’d run out of KPW, I bought only one bullet each. They rolled their eyes at me and came back with guns. The Virgin tried and failed, but the older guide killed a pheasant. They were ecstatic. My stinginess had created a hero. He had killed a bird with just one bullet! He left to grab his prize and came back with a blue plastic bag dripping blood. He winked at me and had the virgin translate that it was a present for me. We would now go to a restaurant and have it cooked for us. It was the first time a man “hunted” to feed me and to be honest, it seemed romantic.

In the van I tried not to stain the seats with the bag and wondered if I had gotten my period yet. We arrived to the restaurant triumphant. The waitresses took the pheasant to the kitchen. As the virgin repeated the tale to everyone around us, the main guide would look down like it was nothing. He was some sort of playboy. The waitresses liked him.

Pheasant takes a while to cook, and ours was done just enough not to get food poisoning. The meat was hard, dry and chewy. It didn’t matter though, we feasted on the legend. We were in Pyongyang after all and the meat was instead delicious, tender, juicy. I asked the waitress for some feathers to keep as a souvenir. The main guy winked at me, again.

After, we went to the Hakdanggol Fountain Park for ice cream. Women heading to Mansu Hill Grand Monument for weddings and celebrations swept across the park, making it look like a glittery cake. Their traditional dresses made of nylon and polyester reflected the yellow sunlight, as did the rhinestones in their tall heels, which made little white drawings on the concrete surrounding the fountains.

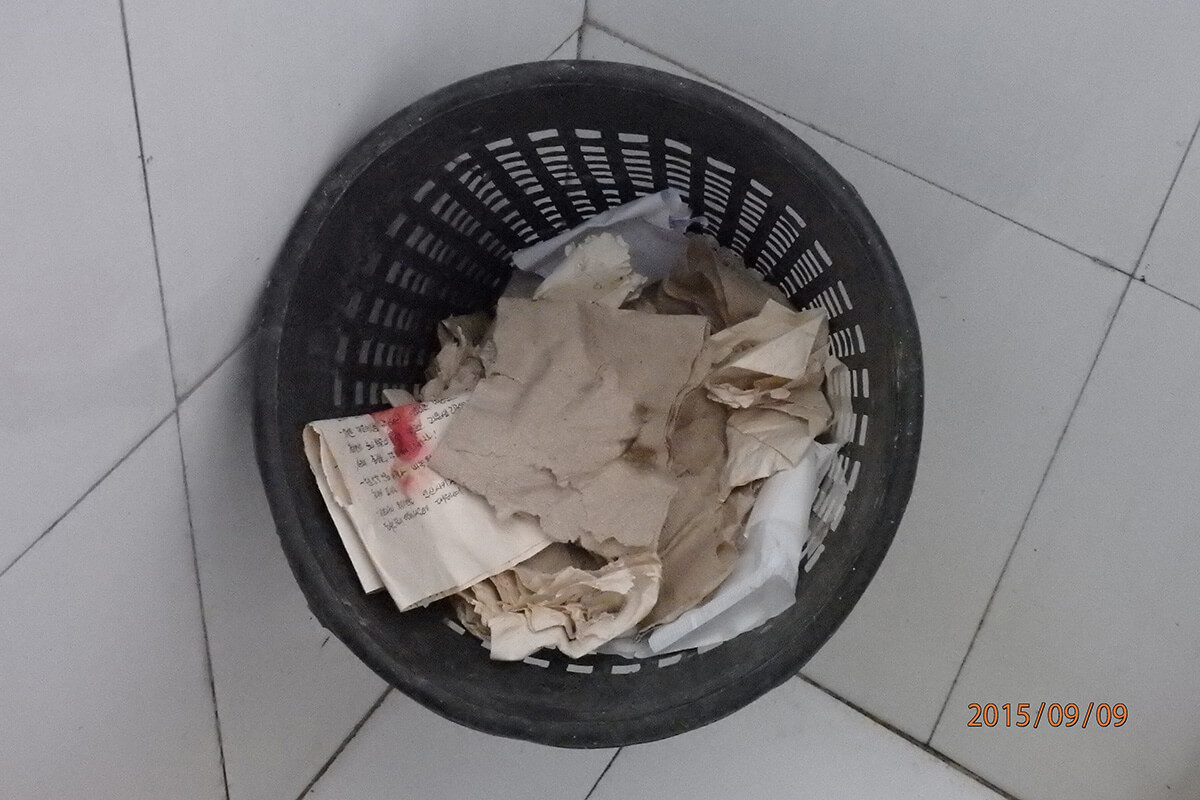

Since arriving, I had seen women walk long distances in high heels. “Don’t they ever get tired?” I asked. My guides replied with a solemn negative: North Korean women never get tired, they are built to wear high heels. Wanting to slap them, I asked to go to the bathroom instead. In the stall, checking my own underwear for a red stain, I saw in the trash can, a torn book page covered in menstrual blood. It seemed that North Korean women were women after all.

It was my last day and I realized I hadn’t had a private conversation with a woman. I had spoken to them in our field trips, yes, but always accompanied by the Tres Reyes Magos, under their supervision. When they asked if I wanted to see a movie with them on my last evening, I declined. I got a massage instead. Not only because the film would be propagandistic, but also because I wanted to be alone with a woman. My communication with other women in Pyongyang had taken place through our body language and our stares. Now I wanted to communicate through touch in a private room. It was nice not to be followed. For an hour I was naked with her.

After the massage, dinner. The guides left me by myself in the restaurant next to the hotel. The food was bad, I was bored and again the same concert of the Moranbong Band was being played on the flat screen. I went outside to smoke. In the DPRK, a woman smoking has the same connotations it had during the Spanish Dictatorship. A prostitute, a harlot, a whore, a woman of the night. Things that now sound silly, as if coming from a movie like Shanghai Express.

So I stood there, right in front of the hotel, at one of the busiest hours of the day, performing for all the pedestrians. For the children coming back from school, who looked at me confused. For their mothers, who seemed outraged. For the working men, who got turned on. And last but not least, for the women who smiled at me. This stupid little transgression was my love letter to Pyongyang.

That night we got drunk. I dreamt about my last breakfast with Tony and even though I was terribly hungover, I jumped out of bed early to make myself look decent. Standing at the elevator, nervous, someone tapped my shoulder. It was the virgin telling me that we were having breakfast at the airport instead. My heart sunk, I wasn’t going to be able to say goodbye to Tony and ask for his postal address. It felt like seeing someone die, and soon I realized it’d be the same for the driver, the main guide and the virgin. My Tres Reyes Magos, I would never see them again.

Used to social media, the idea of a final farewell was painful. A definitive goodbye? How could it be possible, when in the capitalist networked west one is forced to stay in touch. And so it was. I took the city off me like a Band-Aid. Between a clothing store named CLOTHES and a bookshop called BOOKSHOP we had breakfast at a cafe called COFFEE and said goodbye.