The Spirit of '70

Travis Diehl

June 30, 2020

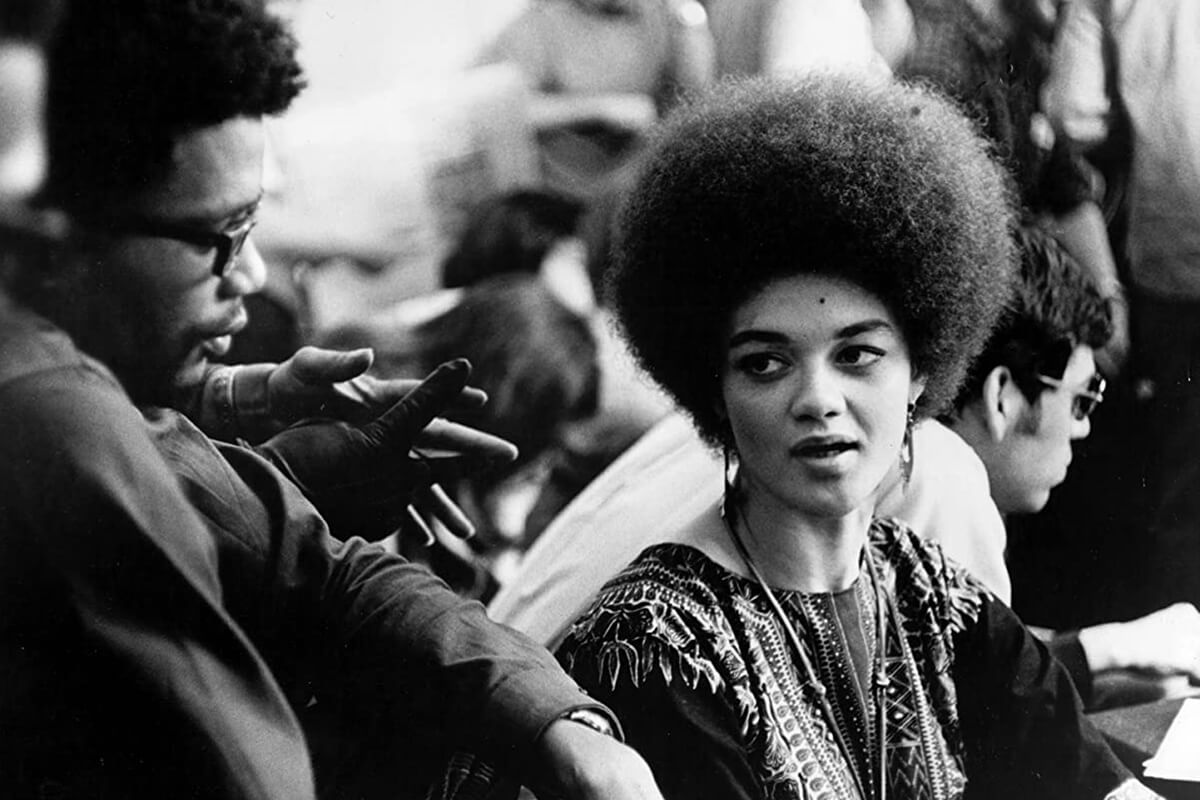

The amber waves of Zabriskie Point’s opening credits harden into its first scene; the psychedelic pumps and skitters of Pink Floyd’s “Heart Beat, Pig Meat” die down so the characters, college students contemplating a strike, can speak. Kathleen Cleaver of the Black Panther Party is there (playing a student, but also herself). So is activist Frank Bardacke. Discussion has turned to the list of demands. A blonde woman wants to abolish the ROTC. The Panther next to Cleaver lays it out: where have all these fearless white revolutionaries been for the last three hundred years? “Molotov cocktails is a mixture of kerosene and gasoline,” he says. “White radicals is a mixture of bullshit and jive.” There are scattered protestations from the white radicals in the room. Are you willing to die? asks one. A Black student retorts: Black people are dying. Mark, our pale, blue-eyed, shag-haired hero, stands up. He is prepared to die, too, he tells the assembly. But “not of boredom.”

How to watch this film today, as the radicalism of the fabled 1960s walks the land once more? I began this essay during a pandemic. Since then, George Floyd’s murder by cop has compelled people to break quarantine and take to the streets, sometimes to confront the police. Molotov cocktails, indeed, have arced through the teargas, thrown by radicals of all races. It is the Movement rephrased for the present. But it is also, more importantly, something new. And in the context of this erupting urgency, Michelangelo Antonioni’s lush, confused film is all the more cautionary, a warning about the problematics of allyship and the seduction of myth. The students launch their strike. Antonioni works his own staged scenes (a standoff in the library, a stricken cop, a Black Panther gunned down) into newsreel of an actual campus uprising at San Francisco State in 1968.

Zabriskie Point is set amid the social strife of the late 1960s—it was released one month before the massacre at Kent State, two months after police murdered Fred Hampton while he slept—but is focused on the story of one disaffected white youth, a rebel without a cause and all that. The plot is violent in an ambient, aimless way. Thus, the film glosses over the great omission of the American myth, the fact that white supremacy has always walked hand in hand with freedom, progress, and the frontier.

It was 1968. Antonioni was riding high on the success of his first English language film, 1966’s Blowup, a dark vision of swinging London, and America was next. America was important, thought the Italian auteur, because America was a future-facing, frontier country, and its youth the most futureward of all. An assistant to the director spotted Mark Frechette at a Boston bus stop shouting obscenities: “He’s 20,” she told her boss, “and he hates.” Antonioni cast him immediately. He found his starlet, Daria Halprin, dancing in a documentary on the counterculture. In Mark’s handsome, almost sociopathically wry face, in Daria’s flowering, innocent limbs, the auteur saw his metaphor: the Movement’s firebrands turning inward, to self-immolation.

Mark and Daria were not actors. They were real, beautiful, white American youths. Daria was the daughter of a Bay Area choreographer, and Mark was a Boston native and itinerant handyman bidding to join Mel Lyman’s cult. Both use their real names in the film. Antonioni used (or tried to use) their real idealism. The director wanted rawness, authenticity, wildness—the West in the Continental mind—and he got it: a shallow-focus misapprehension of the Movement as only a 50-something European man could see it, through a lens as grandiose as it was bitter.

And so, Zabriskie Point is a gorgeous mess. The plot is dumb, the acting (who knew?) is wooden, the dialogue is a labored caricature of America structured by binaries like students/cops, free/trapped, and nature/civilization. The film valorizes free love as much as lost causes. Mark buys a gun, but it never goes off. Daria explodes a building with her mind. Contemporary film critics thought it was a joke. “I want to avoid all clichés about young Americans,” Antonioni had said. He failed. “Corny? You bet your ass it’s corny,” wrote John Burks in a ruthless but romantic review for Rolling Stone. “Antonioni has constructed his movie of so many lame metaphors and bad puns that it’s staggering.” Mark, ever authentic, went on the Dick Cavett Show and told the host, who hadn’t seen the movie, to save his money.

Antonioni’s film was mired in nostalgia for a time that was still unfolding. But, just maybe, the golden gobs of idealism on the director’s lens made for a truer document of modernism’s gasping dreams and its aleatory fallout than he realized. Even its critics admit the gangly plot is slung between images of scintillating pathos and splendor: the opening scene of student radicals rapping in a classroom; the final sequence of a mansion crammed with consumer goods exploding in tingling slow motion; and the centerpiece, some 20 minutes of striking Death Valley landscape, Mark and Daria flirting through it like pretext.

The actors’ lives, too, bear out images to punctuate the era. With the money and fame from Zabriskie Point, Mark was finally let into Lyman’s cult. Daria, his lover for a time, followed him to Boston, but didn’t dig it, and went back to the Bay Area. In 1973, Mark was arrested after a botched bank heist (he claimed it was the closest he could get to robbing Richard Nixon), and died in prison two years later in a suspicious weightlifting accident. Meanwhile, Daria married and divorced Dennis Hopper, star of Easy Rider, the kind of era-defining movie Antonioni had wanted Zabriskie Point to be.

*

Zabriskie Point is an alien outcropping near the east rim of Death Valley that overlooks the sepulchral beauty of wind-hardened canyons of yellow- and rose-gold sand. On any given morning, dozens of photographers gather there to make images of the sunrise. Many leave after just a few seconds of light: evidently, the best part is over quickly.

Antonioni’s film meanders through this scenery for around 20 minutes. As Antonioni said in 1969, during production, “A boy and a girl meet. They talk. That’s all. Everything that happens before they meet is a prologue. Everything that happens after they talk is an epilogue.” The film’s rocky plot is a vehicle for getting Antonioni’s two stars untangled from Los Angeles (prologue), beyond what he saw as a soulless commercial wasteland of billboards and fast food stands and facades, and out to the real stuff: mounds of pulverized minerals.

Everything on either side of Zabriskie Point is the politics of the 1960s, the Movement, the ravages of capitalism and the pigs. In other words, the politics of landscape—conquest, development, when the freedom of the desert was not the freedom to fuck in a national park but to claim, to exploit, to “mine.” They talk, saying nothing much, keeping time, as politics presses in. Suddenly a hundred other couples, like ghosts, nip and prod and pleasure each other in the dust. Then, it’s over. Even in 1970, even to Antonioni’s dazzled eye, the drift into the desert felt predictable. “I always knew it would be like this,” says Mark, post-coital. Maybe he means sex. Maybe he means the desert, or Hollywood film. Maybe he means the revolution. The phrase, cynical and beatific, hangs over the film like haze.

Antonioni’s film sprawls, but leadenly, hemmed in by Hollywood and pressurized by the Movement’s ideals. Mark (epilogue) flies a stolen plane, painted with flower child phrases like NO WAR and NO WORDS, back to the city—even though, according to the radio, he’s wanted for killing a cop. He goes back to die, and civilization obliges him. Meanwhile, Daria meets her boss, a real estate man trying to sell the desert, in a fancy house outside Phoenix. She closes her eyes, and the Modernist dream home, its floating planes and glass walls and naturalistic grottoes, explodes, again and again, from different angles, different zooms. Consumer goods (laundry, books, a fridge) fly to pieces with aching slowness. Pink Floyd scream and mourn for everything America is, and for everything it isn’t—they freak the electric fuck out. It’s a cathartic scene. Antonioni made an image of the psychedelic frontier, a return to the majestic, indifferent bedrock of existence. He doesn’t say who this escape is for. Then the fantasy ends, the house pops back into place, the airborne lawn chairs and Tide-fresh tennis shirts vanish. Daria gets into her Buick and drives into a sunset the color of MGM.

Antonioni understood this much: whether or not there is truth behind the apparition, the apparition has a truth of its own. Today, Mark’s misdirected certainty figures our attempts to find a kind of political vitality without being nostalgic for the politics of the ‘60s—and without being nostalgic for politics. The compromise, of course, is that participating in American politics means also participating in America’s fantasies about itself—these distant, hoary hallucinations that arrive in a barren wash while Jerry Garcia plays guitar.

*

From my first exposure to the California desert, driving a box truck down the deadly straight Pearblossom Highway, I’ve been fascinated by the very real possibility that the Western myth and its genocidal, republican bromides were the key to understanding my romantic but unforgiving homeland. Death Valley, for instance: they mined Borax there, and Ronald Reagan did both Borax commercials and cowboy movies, and was elected president, and hosted heads of state at his Rancho el Cielo, and so on. The image, like Reagan’s white Stetson, fits the plot.

In 2010, for my MFA thesis, I remade Antonioni’s desert scene. I headed to Death Valley with my girlfriend at the time, another MFA. (She shot most of the trippiest footage of dry, wrinkly formations racking in and out of focus, a thousand feet in an inch.) One of our teachers, an auteur of American landscape in his own right, had recommended we stay the night in Trona, a mining town named for the mineral they produce. Trona is perpetually smothered by the fumes from drying ore and dotted with fire-damaged houses from meth-related arsons and accidents. It turned out there was a mining conference that weekend, and the shabby roadside inns were all full. Nothing, either, for hours in either direction.

As the sun sank, we walked into the local Elks Lodge to think over a beer, and almost immediately met with the hospitality of a group of retirees having their weekly supper. They invited us to their table in the back, ordered us Budweisers and spaghetti, and eventually one couple offered to put us up for the night. They wanted us to know, they said, that there are good people in Trona. Also, we reminded them of their grandkids. In the morning, while she made breakfast, he showed us his guns and his medals from Vietnam.

My movie, Walk Thru Walls, mimics Zabriskie Point’s cinematography of Death Valley. There are no actors, but it’s shot as if there are—swaps between blurry mountains, or slow tracking shots along a ridge as if someone is walking, someone else is trailing behind. It’s a landscape film, complete with rapping. The voiceover is just me, talking to myself—one part having a dialogue with another part—chasing after my lover (myself). One naïf side just thinks everything is spectacular, and accepts the desert as it’s given in myth: empty, harsh, transcendent. Another thinks too much, thinks about thinking, fancies himself too wise to fall for that purity shit. He thinks he sees the violence that purity conceals.

There’s a long silence in my movie before the final soliloquy, so it’s hard to tell which “me” is speaking. The passage is a true story about a bunch of cats swarming around the yard of a forlorn post office in the middle of a hot, windy night. That’s the climax of Walk Thru Walls—the counterpart to Antonioni’s dusty orgy, where Mark and Daria’s (or mine and my) duality shatters into something less defined, less binary, a banal but ineffable encounter with fecundity. The way the myth shapes what you look for, and so what you find, but not completely.

A flare flits above the ridge, slowly sinks behind it. I’m writing from another California desert, Pipes Canyon near Pioneertown, where the movie-style roadhouse Pappy and Harriet’s is the last business you pass. My partner’s boss and her husband, both artists in their 70s, bought this small cabin from another artist decades ago. From the porch you can see, hear, sometimes feel the luminous exercises of the Marine base at 29 Palms. Lots of American deserts host rehearsals for blowing up deserts overseas. You can leave Los Angeles, you can slip beyond the reach of television and 5G, but that’s where you’ll find the worst cowboys of all. Beautiful, isn’t it, from this distance; a shooting star in reverse.

Part of me wishes I believed in the promise of an outside, an escape. Part of me, though—the better part—knows that the romance of the outside, the frontierism reenacted by Daria and Mark, mostly serves to distract from the festering wounds of our common inside. Zabriskie Point is a Vietnam War movie in that sense, whether it knows it or not. The Movement screamed to bring attention back home, to real people and real lives in the real fissures of America, while reactionaries and patriots stubbornly tried to vacuum-pack the country into the same old expansionist, individualist myths—selling the idea, one frontier war at a time, that you can always start again beyond the city. Industry and militarism duly bracket Antonioni’s purity, yet for all of 20 minutes Mark and Daria had the luxury of forgetting. Who can afford that luxury now? The violence is no longer hidden behind the rise, if it was ever hidden.

*

Zabriskie Point is 50 this year. Daria is 71. Mark would be 73—Trump’s age, just about—had he lived. Instead, while Sanders was writing about sexuality for an alt-weekly, while Biden was starting his first Senate term, while Trump was dodging the draft (those boomer pastimes!), Mark held up a bank with an empty gun. His death in real life was as senseless as his death in the film. Which is maybe what happens when you’re willing to die, but don’t know what for. I imagine the film of his life flickering across his eyeballs as Mark lay there suffocating in a prison gym, a 150-pound barbell across his neck. “I always knew it would be like this…”

Antonioni understood the American myth’s futureward drive, but not its nostalgia; not its yen for failure, the part where the myth incorporates the desire to escape all myth. He thought Mark’s death would look like a tragedy. But the American myth is a death cult—one built around the image of the outside, veiled nostalgia for white expansionism, the murderous victimhood of the settler huddling in their ill-gotten fort. American myth is dying for a patch of stolen desert at the Alamo. It is one prospector gunning down another for a sachet of gold dust or a worthless claim. You know. Free enterprise.

“There are more important things than living,” said the Lieutenant Governor of Texas, a desert state—by which he meant, specifically, the right to patronize small businesses during this pandemic. Weeks later, as the anti-racist uprisings redoubled, Trump yearningly rehearsed the racist speech of ‘60s strongmen threatening to shoot looters on sight. White supremacy loves replaying its old movies. And so, the ‘60s died—and so they live again. Independent hardware stores and bakeries and cowboy bars shaking apart, exploding in the slowest slow motion… the pages of Zane Grey novels flapping into cinematic oblivion, the brown glass of Budweiser longnecks and Styrofoam plates of spaghetti quivering apart in the mine-stench air…

Even in 1970, as Burks wrote in Rolling Stone, Antonioni’s film simply polished clichés. “Kathleen Cleaver is beyond mere ‘Campus strife,’ now: living in exile, helping her husband Eldridge press for armed revolt within the United States,” he wrote. “We’ve been through too much (Chicago, People’s Park, Altamont, the Chicago Trials, the Panther busts and killings) by now. For this reason, Zabriskie Point seems almost a period piece.” It was a political relic then, and it is certainly one now. Not least because we’ve been through our own “too much”—our own series of violent ruptures, our own litany of almost messianic returns of the genocide that made our country: mass shootings, racist slayings: Freddie Gray, Trayvon Martin, Breonna Taylor, George Floyd; Orlando, Las Vegas, Pittsburgh. We don’t need a film crew to invent an LAPD cruiser in flames outside a mall; teargas in a D.C. churchyard; a Minneapolis precinct on fire; a new generation marching in the glow. We have our own image of America—one that admits, maybe once and for all, that the frontier was and will always be a slaughter, whatever the costumes. There is no outside of time, no reprise of the past—just the now, inside the moment, which is, as always, what we make it.

Antonioni had read in a newspaper about a man who stole a plane, returned it, and was gunned down on the tarmac—a synecdoche for America tearing itself apart, or yearning to fly free, or both. This image was the germ of Zabriskie Point. Antonioni’s film had images down, but not their velocity. So much for the plot. Progress is the modernist narrative, but its failure is the modernist romance. The image Antonioni made didn’t fit the cause, couldn’t encompass and abstract it, any better than the myth already had. Instead, the film became an unwitting image of the idea worth dying for. It’s a picture of how, even if we always knew it would be like this, we always wanted it to be different. But see, there it is: the myth, the image, the mirage. I’m willing to die, but not for a desert, even a desert I love. That’s just landscape suicide.