Better Than Satisfaction

Ross Simonini

May 7, 2018

The addiction to our own taste begins in adolescence and thrives in teenagehood. Tupac posters on bedroom walls, Vonnegut spines on shelves, Siouxsie t-shirts, Air Jordans, Uggs. We establish our identities by staking out a cultural corner of our own. This is the way of our society: specialization.

Later, we learn to drop the right reference into the right conversation, to avoid the hit songs, the blockbusters, and favor the b-sides, the cult films. Secret information is coveted. Acquired taste is the goal. If less people like the music you like, you identify more intensely with it.

As time goes on, the fan can become the aesthete. Negative tastes grows exceedingly important, even more than praise. The aficionado is certain about the work that is impossible to enjoy. We learn to defend our ever-shrinking corner with hatchets. Everything else is unlistenable, unreadable, unwatchable.

Fandom taught me how to become an artist. I spent most my youth attending to the expression of my taste, which is to say, my artistic style. I’m this kind of an artist, not that kind. I became sensitive to all my likes and dislikes, to the world’s opinions, to anything I considered worth considering. The articulation of a note, the weight of brushstroke, a punctuation mark—I could judge it all.

In this way, I slowly constructed my artistic self. I accumulated enough opinions to feel like I could make a good argument for/against any artwork, including my own. I took on the role of critic-as-artist. When taking in new work, I’d scour for triggers: word, color—anything that gave me an excuse to flick another work of art into my ever-growing blacklist of unsuitable art. Anything that didn’t annoy me could stick around.

At that time, my goal was to move beyond that first, rudimentary level of taste refinement—what could now be called “basic”—and build a configuration of preferences that would identify me as a singularly profound human being. I’d mix my fancy tastes (foreign music, experimental video, high fashion) with some mainstream pop culture and arrive at a nice, diverse ecosystem of flavors. My own little fortress of well-rounded taste.

I blame this ridiculous goal, in part, on school. The academy demands us to accept that whatever work they have put before us is legitimate, as if legitimacy could really determine appreciation. From junior high through grad school, I learned about classic movies, so-called “serious” music, canonical literature, and important art. I also learned, through the many glaring omissions in the curriculum, the works that were unworthy of study. These included the lowbrow guilty pleasures we could obsess over in our private time, and the works that were historically ignored (i.e., anything outside the hetero-Euro tradition). If you wanted to be a good student, you learned to have scholastic taste.

School also (primarily) teaches you to navigate social taste. By high school, social groups are best understood by their choice of cultural signifiers: jock rock, Kerouac, Plath, goth, punk, The Dead, Cardi B., Philip K. Dick, Tori Amos, Skyrim, and on. Most kids fulfill their hipness quota by selecting the appropriate cultural artifact for their group, while the more aesthetically-obsessive types learn to gently rub against expectations and reach new levels of unexpected para-hipness.

Perhaps it all seems shallow when described like this, but looking back now, I see myself using art as a symbol, a way of giving myself context. This is how the youth has been defining itself for years, and I knew no other way. I wanted the American dream of liberal, individualistic cultural consumption.

Now, eventually, most people stray from this path. They get older, stop caring. But some keep going, digging deeper into their navel until anything beyond their taste offends them. You’ve seen these curmudgeons—calcified, trapped in their corner, afraid of contradicting themselves for fear of invalidating their entire life. Others go in the opposite direction, allowing their taste to be entirely dictated by whatever mass culture decides to serve them.

Maybe it was after seeing enough cases like these when something in me snapped. One day, I became suddenly, profoundly sick of all my opinions. More importantly, I could no longer accept the idea that my identity was just a group of likes and dislikes. Facebook, OkCupid—our social and romantic connections are determined by our cultural signifiers. We like those who like what we like. If we don’t know what we like, Pandora and Spotify tell us what to listen to, and Google anticipates our opinion based on insidious algorithms that interpret our age, class, gender and race. and yet, without my top-ten lists, I wasn’t sure who I was. Nice? Funny? Italian?

*

So, once college was behind me, I began to actively dissolve my taste. I’d seen enough “good” art for a lifetime and wanted to explore the dark side. I’d begun to feel ashamed for ignoring vast swathes of life experience. How much of the world had I missed in the name of sticking to my position?

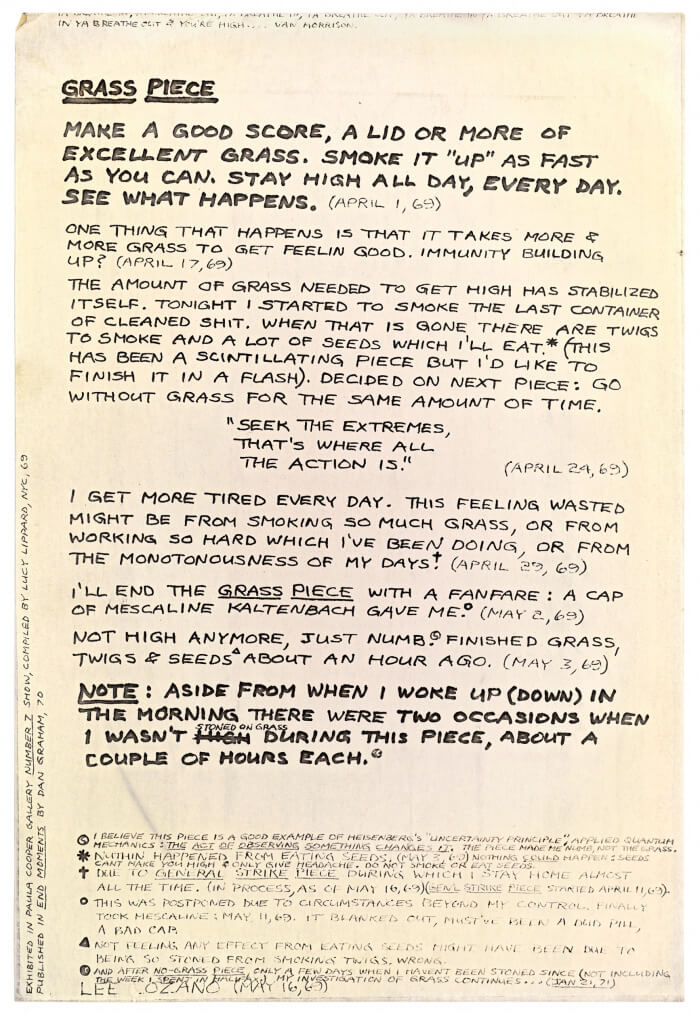

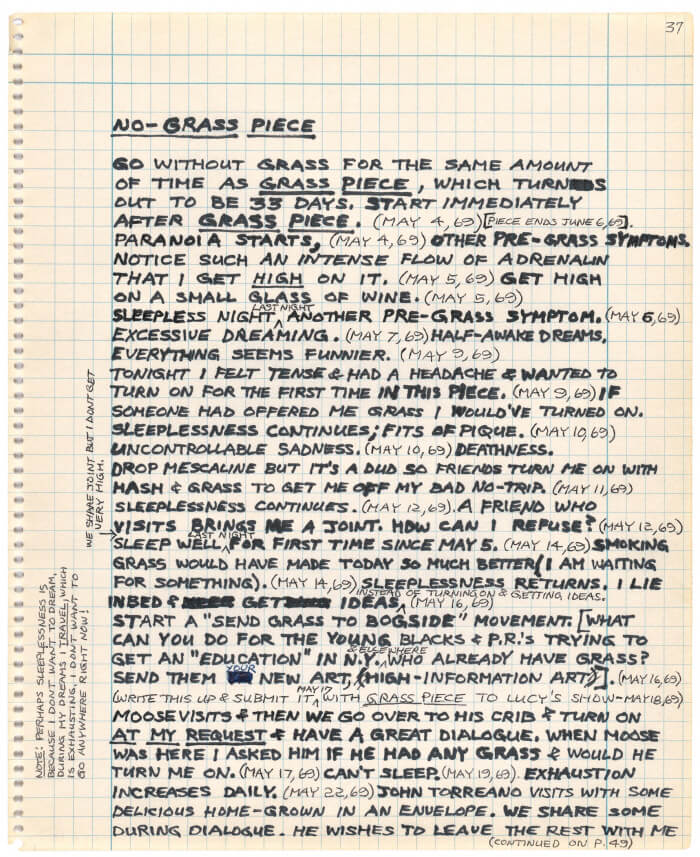

To remedy this, I created an experiment that would last many years. It began with a simple declaration: I will do what I dislike.

Perhaps it’s not the most original thought, but nobody around me was making this choice, and to me, it seemed like the most direct way to reverse my condition. I would move toward whatever repelled me.

It began, of course, with art. I listened to music I had previously considered unpleasant—polka, Chinese opera, mariachi. I dove into film genres I’d rejected or ignored—Bollywood, rom-coms, Hallmark movies, Eastern European melodramas. I read books written in styles I thought were artistically empty—mysteries, erotica. I watched performances that bored me or insulted my attention to the subtleties of human drama. I wanted to take on the high, the low, the hideous, the glitzy.

Time-based forms were especially useful, because, unlike a painting, they required endurance. I couldn’t turn away. I had to go into the work to find relief from my own gnawing disgust. This was how I’d reprogram myself.

*

I realize that the whole process sounds a little masochistic, but, in fact, I wanted to stop all the silly suffering of living as a “cultured” person. That, to me, seemed masochistic: a vast population of educated people who purposely cultivated their own discomfort. Surely, these are the actions of a society that has lost all perspective in life, and I wouldn’t let it get me down too. I’m an artist, and if I’m not absorbing as much pleasure from art as possible, I’m sabotaging myself.

When I stepped into the world, I wanted all the billboards and street musicians, the newspaper articles and unfashionable outfits to become like the trees in a forest. I wouldn’t sit around considering my idiosyncratic reaction to each individual tree. That would be exhausting. Trees didn’t need my approval or rejection. I’d just enjoy the forest, occasionally regard a leaf, and then move on. In this way, I planned to mentally transform the man-made artifacts around me into an environment that might, from time to time, engage me, but would otherwise not draw upon my mental energy in any significant way.

After a few months of following this approach, I realized that my experiences of art had long ago been reduced to a series of footholds for my judgments. Instead of listening to a lyrical melody, I only heard my own opinion of it. I couldn’t really see a painting, I just saw my impression of it. I was trapped inside my own velvety Platonic Cave. It was how I could stay comfortable and certain, which was unfortunate, since one of the great pleasures of art is its ability to surprise. In a world of air conditioners and central heating, art provides the uncomfortable but necessary gust of uncertainty.

*

As my experiment moved along, I expanded into the visceral. At restaurants, I ordered the least appealing dish on the menu. The foulest thing I saw. The foods I had avoided for years. But as I ate, I often found myself surprised to learn that my disgust was not, in fact, built into my taste buds. It was a decision, a stubborn association I had made in my past without even knowing it. Maybe I’d once eaten a bad plate of potatoes au gratin, had vomited lamb, heard a nightmarish anecdote about lima beans. These were perfectly fine foods for which I’d constructed fictional biases, and I’d done this because I thought it was beneficial to dislike something. It showed I had boundaries. And yet, when I actually put the food in my mouth, I didn’t dislike it. I didn’t even have to acquire a taste. I just had to stop hating.

Same went for questionable smells. I took a big whiff. When I heard shrill music, I focused on it. I was eager for the unpleasant, and bored by the unconflicted experience. Discovery felt better than satisfaction.

Encouraged by my small success, I applied the experiment to my social life. I found people who bothered me immensely, for no good reason, and I spent hard time with them. When they did something intolerable, I faulted myself for being unable to see their good sides. Sure, if they tortured a rabbit, or told a xenophobic joke, I’d feel justified in walking away from them, but for the most part, these people were fine. I’d only been nitpicking their facial expressions, the treacly phrases they dropped, their cringe-worthy avocations, or most likely, their uninspired taste. But when any of these subjects arose, I just asked myself: who was I to judge?

And the more I pushed, the more my sharp senses smoothed. I didn’t love all foods, but by then, I didn’t dread eating anything. Why should I feel distress (or even pain) when eating something nutritious? Or reading a book? Or spending time with a jerk? I could find ways to tolerate them all, and I did. None of these experiences were tangibly harmful to me, so why should I act like they were?

I had to remind myself that taste itself could become dangerous. It could keep me at a distance from the world around me, and transform every aesthetic experience into internal masturbatory conflict.

And so, the inner drama of my taste quieted. I gradually undermined my fragile identity. I grew disoriented and became pleasantly child-like. My taste became a malleable material to use for play. I reverted back to the stage in life where opinions were like alien parasites that inhabited the people around me—extraneous, toxic. I took none of my preferences for granted. If I wanted an opinion of my own, I’d have to actively make it, and then codify it into my personality. It would take time and consideration, so it better be worth it.

Unlike being a child, though, I now knew I had the ability to create as many shiny opinions as I wanted. I could spend the rest of my life building a great collection of opinions, or live lightly, vagabond-like, not a single viewpoint to call my own. For the first time, I could choose.

Eventually, I escaped my pattern of reactive, thoughtless opinion-making. And where all those opinions had once been crammed, I now had an empty space. Over time, this was filled with curiosity, a compulsion that thrived in the absence of certainty and inevitably nudged me out into the expanding unknown.

*

As I neared the end of my experiment, I decided to, once again, test my boundaries. In the beginning, I had been vigilant and jacked up on the power of my will. I wanted nothing pleasant around. Eating a tasty meal, I thought, might corrupt my delicate state. But as I entered my second year, I allowed old, easy joys to creep back in. I’d listen to the Bonnie Raitt album my mom used to play around the house. Eat a grilled cheese sandwich. Watch a film that let me feel like I’d seen humanity flex its artistry as well as it ever would.

Thankfully, these simple pleasures didn’t disrupt me. I didn’t feel less pleasure, and I didn’t return to worshipping at the altar of good taste. So I allowed my experiment to fade. The world grew a little more pleasant and every so often, I’d find a nice, hateable chunk of culture, so I could savor my repulsion in full bloom. After all, it’s the natural human condition. Just another way to stay amused.