Girls' Room

Thea Ballard

September 24, 2018

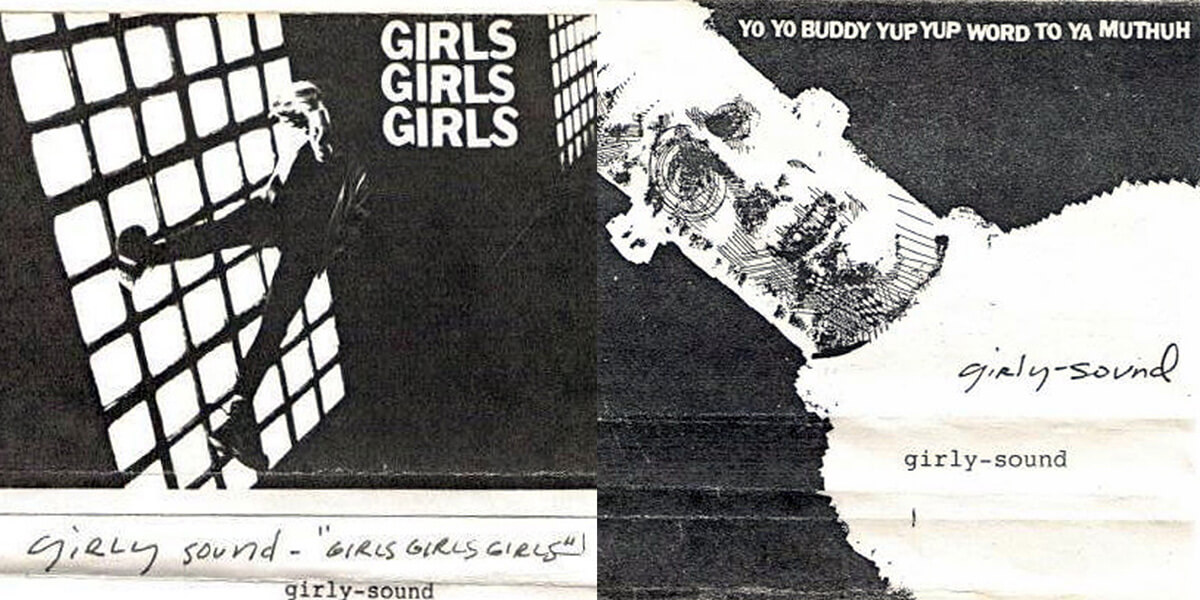

Sarah dumped a mess of mp3s from Liz Phair’s Girly-Sound tapes onto my computer I think during summer 2012, when we lived together on a summer break from college. Cool as we were, part of our thing was a funny obsession with Lilith-Fair-era singer-songwriters, Ani DiFranco and Sarah McLachlan, never mind that I still quite seriously listened to Dar Williams on headphones and cried every time I missed my mom.

Too crass for our parents back in New England and too cool for the soundtrack to Dawson’s Creek, which we were watching for the first time on Netflix in our disgusting sublet, Liz Phair held no trace of irony. I can’t speak for Sarah but those songs put a lot of stuff in my late-bloomer’s consciousness: plainly, sex; as well as the fracturing nature of relationships, and maybe most importantly the often-painful idea of reveling in your own desires whether they’ll go fulfilled or not. Plus, especially on those static-streaked tape recordings, they sounded so cool, as cool as the all-boy tape-label lo-fi pop I was always trolling for on the internet, but less disposable.

Her music was a late but essential addition to the cultural glue that has helped bind Sarah and I together as we grow older and farther from home. About to ring in the twentieth year of our friendship—we met as second-graders in the rural Vermont town my family had moved to in the late ‘90s—it was a happy, even poignant surprise to get tickets off a waitlist to see her play songs from the Girly-Sound tapes in a small venue in Williamsburg.

The caveat? Maybe there’s a little narrative death that occurs when you take something you’ve privately loved and experience it, in person, in public—its expanded cultural context, its market, made undeniably visible. This is an old enough story, but also one that’s been bloated a bit by the internet, right? I feel it as a loss of innocence, a young sensation I’ve stayed embarrassingly prone to well into adulthood.

Less selfishly, let’s call the tour on which this show was a stop, and the reissue of the Girly-Sound tapes and the attendant press, a celebration of a barbed kind of intimacy that Phair pioneered two and a half decades ago. Given my age, I heard and loved her 2003 hit “Why Can’t I?” at least five years before “Fuck and Run.” Indeed, perhaps also given my age, I don’t have that reflexive distaste for radio-engineered pop, and am fond and respectful of her later “sellout” albums, unlike the mostly-male music writers who covered them upon their release.

Nevertheless, it’s nice to see how her messiest stuff, which could easily have disappeared, has developed a presence beyond the marginal. That itself is a kind of validation: that anger and vulnerability felt by women are not necessarily marginal experiences—that many of us can agree that complicated, feminine shit is interesting and necessary and something we’d like to consume.

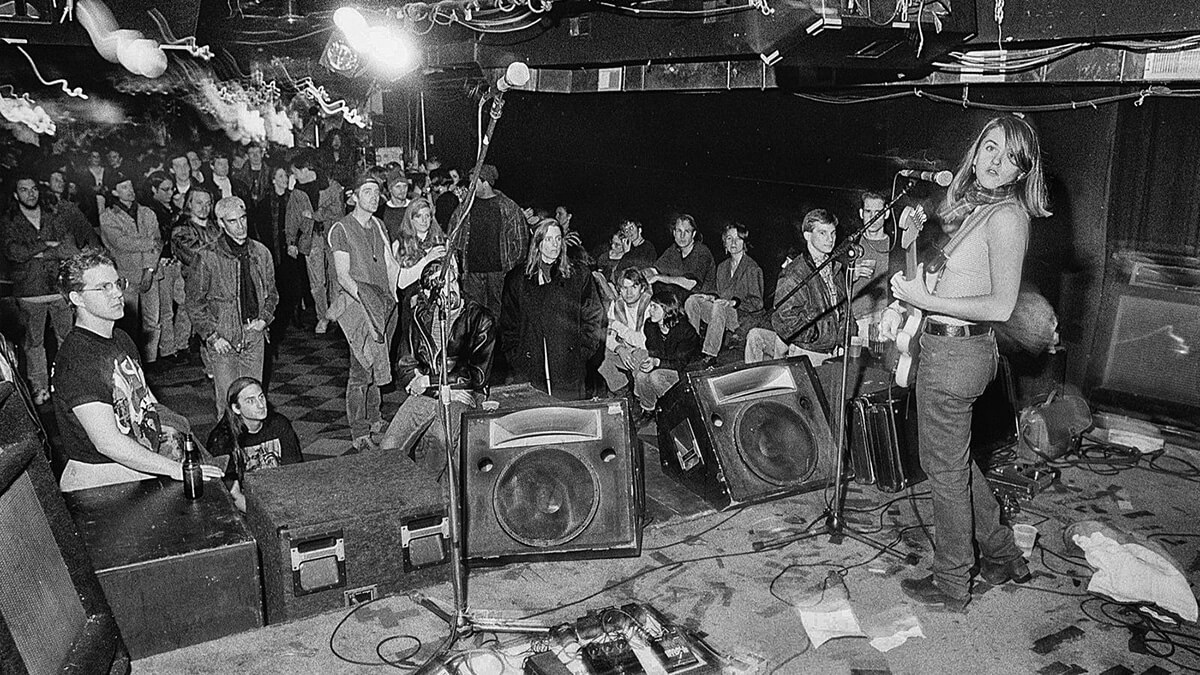

Many people in attendance were grown up—like, a decade or two more grown up than me grown up. There were a lot of middle-aged couples, a mother with bored preteen daughters, a Lilith Fair lifer who asked Sarah and I if we’d “seen Liz before” and commiserated with us on the proliferation of tall men—“trees”—who seemed to have missed the recent mainstreaming of a girls-to-the-front ethos.

Liz was grown up too, a winsome performer who moved through her songs with both a sharpness and easy charm. There was some relief in thinking about how she was performing, rather than living, these songs, effective as that performance was. At one point, she remarked something to the effect of feeling like she had stumbled across the audience in her bedroom. A sweet reminder of the music’s genesis, though hard to receive without a dash of consumer awareness, adult suspicion. Whatever: several times throughout the concert, I felt a warm rush of emotion, the urge to grab Sarah’s hand.

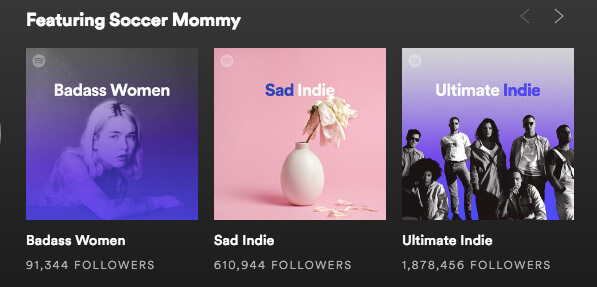

The opener for this show was Soccer Mommy, a musician in her early 20s who is in a sense a product of the Girly-Sound effect. In another sense, she’s very much a product of a lot of stuff specific to her (and my) generation, a Spotify-native artist rising from an underground that’s staked to social media and DIY streaming platforms like Bandcamp. The compact guitar riffs that scaffold her songs are addictively gloomy; her voice, even on her more trained-sounding studio debut from this year, Clean, has a congested quality that makes everything sound off-the-cuff and personable.

Though praised for the Phair-like vulnerability of her songwriting, I’d argue her music is distinct more in its atmospherics, vaguer in its storytelling but evocative in a broad, moody way. There was an awkwardness to her stage presence that bugged me mostly insofar as it reminded me of exactly how I might have acted in my early 20s if presented with a demi-professional situation in which I had to address an unnervingly respectful group of people mostly in their late 30s and 40s as Myself—a sort of Twittery brashness, attempts to bat around a group of people who were too enthusiastic to be feasibly antagonized.

When I used to play shows, between let’s say 2008 and 2014, I played goofy and even dumb between my extremely serious songs (among which was a cover of my very favorite of Phair’s Girly-Sound recordings, “Ant in Alaska”). I’d tell self-deprecating jokes I’d thought of in the shower three days before, that kind of thing. It felt both necessary and very, very embarrassing to sing in my half-broken way about the things I sang about (home, my parents, a car accident, wanting and not quite having relationships, general existential anxiety, assorted growing pains).

I continue to enjoy making fun of my singer-songwriter “career,” but when I actually played the music I accessed a sincerity I clearly had not come to terms with as a performer or a person in the world. Nice things happened. For example, sometimes people who meant a lot to me would cry when I played, which, in addition to the sort of manic buzz of catharsis, was really all that I wanted out of playing music—examining and sharing and feeling the things that overwhelmed me or evaded comprehension. I genuinely don’t mind being on stage, but the last time I played in front of an audience my foot began to violently shake, as if my body itself were rejecting the possibility of my being seen in this way by 15 or 20 people in a Poughkeepsie basement.

Sarah and I, both now professionals in the arts (she works in film production), recently had a conversation about being failed artists, me with my music and her with filmmaking, both of us inclined toward coming-of-age narratives and aesthetics of diaristic unevenness. I mean, not failed in the sense that absolutely no one wanted our stuff, but failed in that our respective proximities to real platforms for what we were making seemed to have somehow spooked us out of continuing to make anything in those veins at all. For me, and maybe for her, this is about that aforementioned fear of being seen, which is tough to navigate when your main artistic impulse is to expose the raw.

But somewhere along the way it became evident, in a way that outpaced the healthy idea of having an audience, that there was demand, a market, for these raw things. With music, in a material sense the product is easy to produce (she’s making it alone in her bedroom), and something we’re nearly always running in the background or on headphones.

In “The Wry Young Women Writing Sad, Buoyant, Beautiful Songs,” published this spring in the New Yorker, Jia Tolentino wrote about a group of musicians including Soccer Mommy, Mitski, Lucy Dacus, Snail Mail, and Jay Som. She hits on the habit-forming everyday quality these artists share: “a sort of music that I have started to rely on, as if its sound were an inner tube on a choppy river, something I could rest on, turning my face to the sun… I found myself taking wrong turns on short drives so I could listen to these artists on repeat.”

I might—cynically, to be sure—offer an adjacent interpretation of this reliance: that it can be characterized by a passivity, that the emotional experience we have while listening can be vague enough to leave us fully functional while we saturate ourselves in it. Though it arrives with many of the signifiers of DIY, DIY for consumers today generally indicates a desirable aesthetic, rather than an ethos: the sound of Bandcamp, the sound of homespun, the sound of the self-made young woman. And, in for-profit spaces in which it proliferates, industry gets to shape supply and stoke demand.

The danger here, I think, is that for this or any music to function as well as a streaming service impels it to, it has to dull a few of its unruly edges. At least Phair had a little time to grow up; any younger artist on Spotify’s “Badass Women” playlist was likely confronted with algorithmic imperatives early on. I’m a little surprised to recall a penultimate line from a song I wrote when I was maybe 19: “Maybe we don’t need to wear our youth till it’s threadbare.”

I don’t mean to accuse musicians or their labels of trying to get rich, of course (is anyone who’s not a streaming-platform or advertising executive really getting rich off of music these days?), but to think about the implications of professionalizing what are to me the vital bookends of these production cycles: songwriting, and listening to songs—both of which I revere as processes that might not only keep us afloat in rough water, but help us undo and rebuild ourselves. Some semblance of privacy, or at least intimacy, real intimacy, seems paramount. We call it bedroom pop, but if intimate space and our transmissions from within it are so professionalized, is there even a proverbial bedroom to make music from anymore?

I’m reminded of the 27-year-old comedian Bo Burnham’s film Eighth Grade, which I saw with Sarah and wish she had made instead. Taking its cues from Burnham’s own beginnings as a teenaged pro-bono YouTuber, it’s been critically lauded for its allegedly authentic portrayal of the pains of contemporary girlhood. Its protagonist, Kayla, is a friendless and painfully awkward 13-year-old who seems to be going through a lot but communicates very little, whether in her conversations with her single father or her cruelly disinterested classmates. In her free time, she vlogs on YouTube, the medium ostensibly a solitary outlet for the character to share something of herself. Instead, like the rest of the film, her self-filmed passages are devoid of an internal life or any real complexity, registering to me as a kind of harsh joke at the expense of her private urge to express.

The punchline is how weak her imitations of real performers are; the film leaves little else to be gleaned. Though the film sets itself up alongside a triumphant arc—she does wind up making a friend, a weird, funny boy who doesn’t seem like he understands her much better than anyone else and who comes across onscreen as more magnetic than Kayla—I remained unsure what story it was trying to tell, troubled that Burnham himself didn’t seem to see or understand his heroine.

Around the time I stopped doing music, for what in retrospect I might categorize as mostly immature reasons, including feeling that playing sensitive indie-pop would make me seem immature to my new peers in the art world, I became interested in media art with diaristic impulses. I was thinking about the construction of the self, and the pleasures and horrors of being seen, in Ann Hirsch’s webcam videos, Amalia Ulman’s social media performance Excellences and Perfections, Moyra Davey film-diary-essays, K8 Hardy’s daily outfit self-documentation.

I feel a bit like a broken record, rehashing those concerns: the wanting and needing and then pain of being seen. It is, of course, all in the service of figuring out what to do with all the feeling that continues to slosh around in my consciousness. I imagine it’s true for many of us that the less we make, however privately, the more stuck we become.

So now it appears I’m thinking about how to grow up again. If we’re really following a diaristic impulse, and if we’re seeking communion and growth, some evasion will be necessary. Something I kind of love about the arc of Phair’s career is that you can look at her “selling out” as its own form of evasion, one that inverts the stakes and double-standards of marketing yourself as a “respectable” indie musician. It’s not like many or most of the younger musicians I’ve mentioned aren’t also keenly aware of the consumptive economies their images and work circulate in, and some place boundaries around themselves in elegant and interesting ways.

Mitski, arguably the most famous of this milieu, has leaned away from DIY marketing narratives and towards a self-consciously performative rock-star persona; she manages a balancing act of coming across as bracingly human in her musical persona while being admirably unforthcoming in interviews. And I wrote about the codedness of Frankie Cosmos’s, aka Greta Kline’s, songwriting in that article about Amalia Ulman and diaries for DIS in 2014. Kline, four years on, continues to react to the hunger of the market with less a capital-p Performance, more a form of self-encryption through her oddball poetics. Both give examples of boundaries, which are challenging to set but so important when your livelihood is extracted from your art is extracted from your life.

Another alternative: This spring I saw a performance by Sarah Michelson, a choreographer and dancer about Phair’s age, which comprised a series of tricky and opaque songs, dances, and soliloquies reflecting on Michelson’s history with the space and organization and neighborhood that hosted her. We were seated on squishy beanbag-like objects, and the stage was all around us, littered with sculptural objects that wouldn’t always come into play as props or set pieces. Some of these objects (I recall, in particular, a little sculpture of a bird with mechanized wings flapping) seemed to represent a sort of encrypted personal iconography. Still, in some way, the performance’s emotional center of gravity was very simple. Michelson repeated two plaintive refrains: “I’m old,” and “I’m sad.” (If you boiled down most of the work I’ve made, it could probably be drawn along similar lines: “I’m sad,” and “I’m getting older.”)

But their expanded containers refracted these ideas in wild directions. There was Michelson’s vaguely abusive relationship with a few interlocutors (a man playing the role of her cat, a younger woman too-energetically enacting Michelson’s choreography), an esoteric array of sculptural ephemera placed throughout the space, musical sequences accompanied by drum-pad instrumentation, all manner of references to scene-y New York City stuff I’m mostly too young or uncool or new to remember. It was abrasive, too. At one point, she looked me in the eye, saying dismissively, as if she could tell I sometimes complain the opposite: “You’re not old.” Once again, terrifying (thrilling!) to be seen, even if only for a split-second and in the service of someone else’s performance.

But, though open to the public and a little bit upper-crust-y in the way smart institutional events are wont to be, Michelson’s performance could also feel like it was occurring among friends: if not literal friends, then a community linked by its willingness to expose itself to the sharp angles jutting off her intense expressions. I regretted not bringing Sarah, who, though she couldn’t have guarded me from getting called out by Michelson, probably would have found it very funny, and would have had all kinds of shit to say that would have helped me sort through the event, and let it burrow its way into my life a little deeper. In the absence of platforms and cultural structures that make it possible to speak and hear clearly, at the very least there is the space between us.

Do you know that Liz Phair song “Girls’ Room”? It closes her 1998 album WhiteChocolateSpaceEgg, a midpoint between her tapes and her pop stuff that includes studio versions of a few Girly-Sound songs. I’ll freely admit to not totally knowing what the song is about, lyrically. Commenters on the website Songmeanings.net have variously and unhelpfully posited that it’s concerned with “sitting in a toilet stall at school never wanting to come out,” being in a sorority, and adult nostalgia/weight gain.

It’s a warm and sparse present-tense or even anticipatory narrative of friendship. We meet Phair the narrator’s “best friend Tiffany.” We understand that she and the girls in the girls’ room might be slutty (“Me and Tiffany/Dressing up pretty/We love to ride/We love to canter”), might be bitchy (“And we hear Terry say that Tricia’s okay/But she ought to learn to shave her bikini line better”), and we can assume they're at least a little insecure; it's hard to call that utopia. But the girls’ room itself, the place, feels inscrutable, like a secret we’re sharing. If we think for a second outside the fragile borders of the song, it’s of course still intersected by all the bullshit of this world. At the same time maybe there’s still something weirder, harder, better that we’re willing into being inside it, especially when we sing for each other or listen together.

Privacy isn’t necessarily about being alone with yourself; it’s also about what you share with people, girls, you really trust. “I’m sleeping in the girls’ room/I’m sleeping in the sky/I’m sleeping in the water”: the girls’ room contains dreams and voids. I’m sleeping in the girls’ room tonight.