No One Wants It

Andrea Long Chu

November 5, 2018

As a lightweight behind-the-scenes look at a critically acclaimed television series, Jill Soloway’s new memoir She Wants It: Desire, Power, and Toppling the Patriarchy is just south of worth purchasing at the airport. As a book about desire, power, or toppling the patriarchy, it is incompetent, defensive, and astonishingly clueless.

This is a story about someone who responds to criticisms of her TV show by taking “a glamping writers’ retreat” to El Capitan: “We had a shaman come. She did magic incantations as we lay on the floor of a yurt.” It is an unwitting portrait of a rich Los Angeles creative type with a child’s knack for exploiting the sympathies of others, a person whose deep fear of doing the wrong thing was regularly outmatched by an even deeper distaste for doing the right thing. The nicest thing that can be said of this oblivious, self-absorbed, unimportant book is that it proves, once and for all, that trans people are fully, regrettably human.

The substance of She Wants It, such as it is, concerns the author’s time working on the show Transparent, whose premise—a Jewish transgender woman comes out late in life to her adult children, throwing the whole Pfefferman family into disarray—was drawn from Soloway’s own experience as the child of a late-transitioning trans woman. In 2014, back when the words “Amazon original series” made as much sense as the words “Jim Carrey solo exhibition,” Soloway, then a married mother of two, could believably protest to Rolling Stone that the show’s explorations of gender and sexuality were “not really autobiographical.”

But as this book confirms, Soloway’s life has rapidly imitated her art. Like Sarah Pfefferman, she would leave her husband for a woman; like Josh Pfefferman, she would become a successful entertainment industry player, in douchebag shades and trousers with kicks; like Ali Pfefferman, she would date a celebrated lesbian poet and experiment with a nonbinary gender. Soloway now identifies as trans and answers to both she and they pronouns, telling CBS This Morning, “She is fine; when people say she and her, I don’t correct them, but when people say they and them, it’s like frosting.” Consider this review a muffin.

The truth is, Soloway appears to know little more about trans people now than when she began production on Transparent. She Wants It suggests that when she wrote the show’s pilot, Soloway thought of trans women like her parent as little more than crossdressing men, and the lessons conducted by writer and series consultant Jennifer Finney Boylan (and subsequently trotted out by Soloway on her book tour) are appallingly basic:

The word “trans” is Latin for “bridge,” she taught us next. Then she wrote the word “transbrella” on the whiteboard. “Not everyone is at one end of the spectrum or the other,” she explained. “People use the word trans to refer to all kinds of people, including drag queens, butch lesbians, and genderqueer folks, who metaphorically stand on the bridge, in the middle, rather than using it to cross from one side to the other.

As far as I can tell, the hideous portmanteau transbrella is of Soloway’s own inventing. (Boylan likely used the usual term trans umbrella.) “Bridge,” meanwhile, is a spurious translation of the Latin word trans, which is a common preposition meaning “across.” Evidently no one at Random House could be bothered to crack open the old Wheelock. Do bridges go across things? They do. May one go across a bridge? Reader, this cannot be denied. But I hope, for Boylan’s sake at least, that the Transparent team was told that trans may be thought of as being like a bridge, for pedagogical purposes. This would have been a metaphor, a word which comes from the Greek metapherō, meaning “I carry across”—for instance, across a bridge.

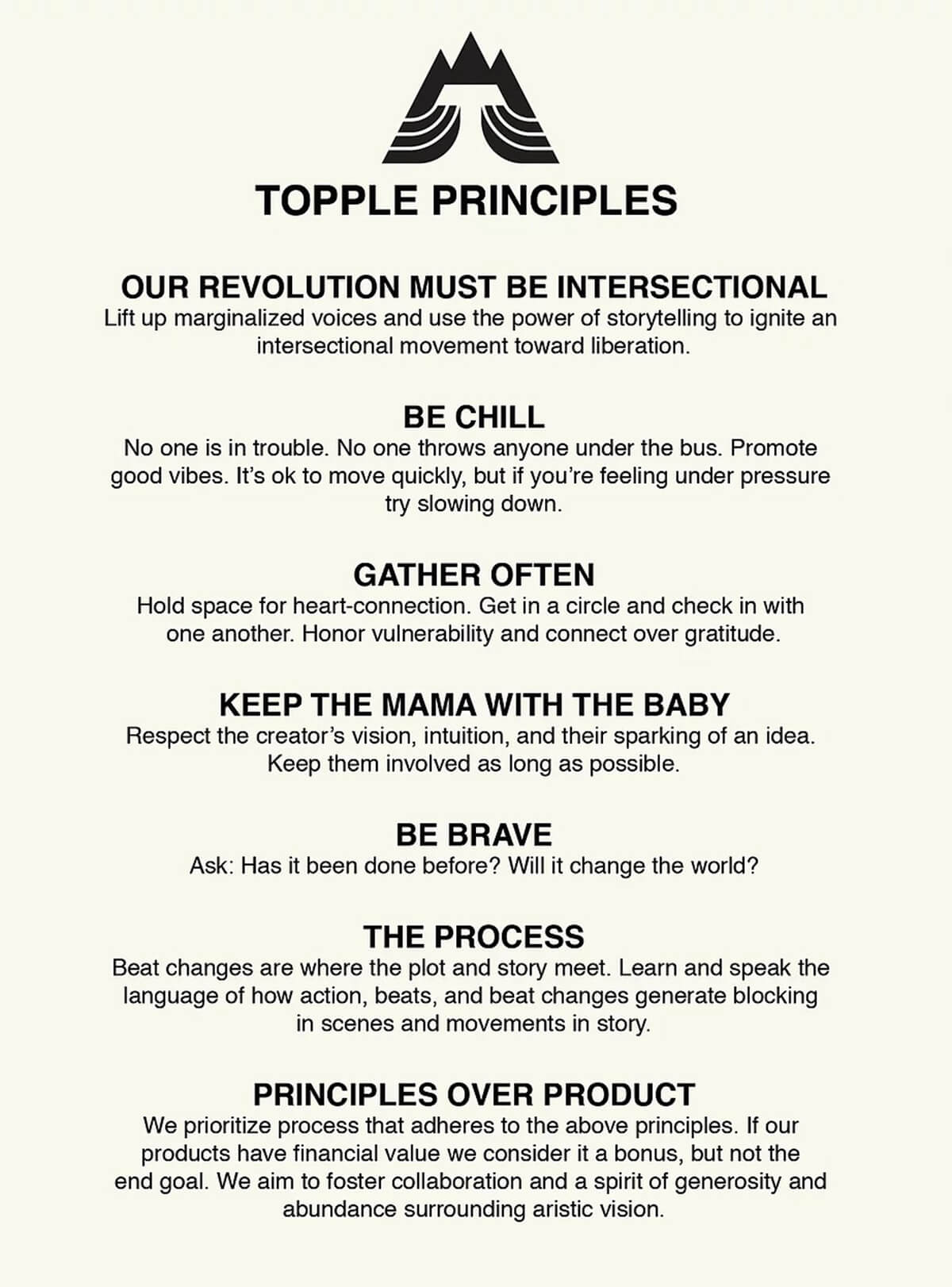

None of this matters, because Jill Soloway lives in a world where the words “radical trans” can be followed, without a hint of irony, by the word “content.” Her production company Topple, which featured prominently in a recent, glowing New York Times profile, models its core tenets after Amazon’s corporate leadership principles. (Number 2 is “Be Chill.”) In Soloway’s voice, one finds the worst of grandiose Seventies-era conceits about the transformative power of the avant-garde guiltlessly hitched to a yogic West Coast startup mindset that speaks in terms of “holding space” and “heart-connection.” It’s like if Peter Thiel were gay.

But self-importance alone could never guarantee writing this atrocious. Narcissism can be wildly compelling in the hands of a professional. That this is the prose of a celebrated television auteur may be explained only if one recalls that TV writing, unlike the art of memoir, is a group effort. The narrator of She Wants It is a Gen Xer in millennial drag: precious, out of touch, and exceedingly prone to bathos. Without a second thought, she rattles off lines like “I woke up with a Zen koan in my head” and “I decided I would have to have an interesting life if I ever wanted to be like Jack Kerouac.” The following is an actual sentence: “As we all took over the bowling alley, the sheer variety of the ways to be queer and alive in Los Angeles in 2014 exploded my mind.”

Soloway introduces deep-sounding quotes from other authors like a middle-schooler phoning in a Kate Chopin paper. She mixes metaphors like a bartender in a recording studio. An urge to break up becomes “that anxiety snowball racing down the mountain at my back that I inherited from my mom.” Can snow be bequeathed? She lovingly refers to her sister Faith as “actual liquid faith,” a figure of speech which, being presumably analogous to the common nickname for alcohol, would only make sense if her sister were in fact a beverage. Also, fragments.

Throughout She Wants It, Soloway alternates, confusingly, between contradictory sites of gender enunciation. One moment, she will wax poetic about “not having to choose” a binary identity (“How would it be if everybody saw pure soul before gender?”); the next, she will breezily reference “our lives,” “our bodies,” “our interests” as women. There exist intelligent attempts to think through contradictions like these (Laurie Penny’s work comes to mind), but this is not one of them. Readers would be forgiven for thinking Soloway a fair-weather woman: female when it’s culturally advantageous to be female, and not, when it’s not.

The ethics of gender recognition, now more than ever, compel us to accept without contest or prejudice the self-identification of all people. They do not, however, compel us to find those identities likable, interesting, or worth writing a book about. Soloway certainly makes it easy to believe the longstanding charge that she sees trans people as creative oil to be fracked. “Something about my parent coming out immediately shattered a wall,” Soloway writes early on in She Wants It. “She was being her true self, a woman. Now I could be my true self, a director.” If the circumstances of her shiny new gender are, shall we say, suspect—the cisgender creator of a television show about trans issues, long criticized for presuming to speak for trans people, comes out as trans herself—all we need remember is that being trans because you want the attention doesn’t make you “not really” trans; it just makes you annoying.

Over and over, Soloway worries if she has made a wrong turn, before plowing ahead regardless. Over and over, she anxiously seeks the counsel of others, only to blithely ignore it. She has regrets, but never remorse: the problem is not that she has made a poor decision, but that someone else has gotten offended. Before Transparent goes to series, Jenny Boylan warns that Soloway will face “a fair amount of blowback” for casting Jeffrey Tambor as a transgender woman. When an audience member raises this very objection at a festival, Soloway cries. “My God,” she writes, “I hadn’t been expecting this.” (Boylan has called She Wants It “provocative, generous, and inspiring.”)

When Soloway gets a Ziony itch to film season four of Transparent in Israel—“I don’t have a lot of things in common with Jared Kushner, but low-grade Jerusalem Syndrome might be one”—the writer Sarah Schulman cautions that breaking with the Palestinian-led boycott movement will put the show in hot water with many queer activists. “Ugh,” writes Soloway. “I was so annoyed. How did I get stuck in this very narrow place of being forced to choose?” (Bafflingly, this is a callback to Soloway’s description of being nonbinary.) Eventually, she buckles, filming the season on the Paramount lot—before taking a small crew to Israel to shoot B-roll. Soloway will later refer to this solution, incomprehensibly, as “our Israel compromise.” (Schulman has called She Wants It “a rollicking tale of how an enmeshed family sometimes brings out the best.”)

But nothing is more cringeworthy than Soloway’s account of the #MeToo movement, with which the book (and indeed, Transparent itself) concludes. “Two years after I’d yelled ‘Topple the patriarchy!’ onstage, it all indeed came tumbling down,” marvels Soloway, breathlessly equating the firing of several famous men with the end of a regime as old as history itself. Our author often appears to believe she can take history’s pulse by glancing at her own Fitbit.

Here she is reeling from the 2016 election: “We thought we had power, but no, actually, we were this thing—this Other Thing called Women, and we could be silenced, disregarded, with a vote.” (Never mind that for every nine women who voted for Clinton, there were seven who voted for Trump.) Now here she is attending early Time’s Up meetings with Reese Witherspoon, Ava DuVernay, and other celebrities: “I went home overflowing. The revolution was happening.” It seems never to occur to Soloway that she might be conflating global upheaval with a sudden influx of rich and famous friends.

All this is damage control, of course, for Soloway’s own scandal. If She Wants It has any purpose, it is to exculpate its author in the matter of Jeffrey Tambor, who in November 2017 was accused by his former personal assistant Van Barnes and his ex-costar Trace Lysette—both trans women—of on-set sexual harassment. At this, it fails miserably. Indeed, it comes as no surprise that Soloway’s leap into Transparent was “powered by a wild jealousy of Louis C.K. and Lena Dunham,” both acclaimed creators of television shows in which they played unlikable, narcissistic versions of themselves, only to be revealed as unlikable narcissists in real life.

Neither escaped #MeToo unscathed. The same month as the Tambor allegations, the Times reported on C.K.’s penchant for jacking off in front of female coworkers. Days later, when actress Aurora Perrineau accused Girls writer Murray Miller of rape, Dunham issued a confident statement of support—for Miller. On Twitter, she appeared to defend herself: “I believe in a lot of things but the first tenet of my politics is to hold up the people who have held me up, who have filled my world with love.” This is what omertà would sound like if you bought it for $79.99 on Etsy.

If a Mafia analogy seems crude to you, hold that thought. “I needed to find out why she was going straight to the press with her story, to understand why she hadn’t come to us,” Soloway writes of Lysette. “We could handle this, I wanted to tell her, but let us do it internally, inside the family.” Soloway is never so sulky as in these pages, pouting about her “legacy” and losing any lingering ability to complete sentences: “If Trace released a statement, it would be over for Jeffrey. And that meant Maura. The show. Our TV family. Everything.” In a climactic, chapter-ending scene, Soloway parlays with Lysette at a Coffee Bean picnic table. “I can’t believe you’re doing this,” she tells the actress. “Well, it happened to me,” Lysette coolly replies. What happens next is so incredible that I must quote it at length:

“I had to tell my story,” she said. “But I said in my statement that I wanted the show to continue.”

“But the idea of the show will be tarnished now in everyone’s minds,” I said. “In Middle America when people think of trans people there’s still so much suspicion, and Maura became this beautiful symbol of transness and now you’re laying this imagery out there of her being a predator.”

Suddenly, I started crying.

She was horrified.

“I’m the victim here and YOU’RE crying?” she demanded.

She was right. I was sitting across from her, frozen with fear. I tried to stop myself from crying. Like Michael in The Godfather, I tried to play it stoic and cool. I didn’t say, Fredo, after all I’ve done for you. I said, “I wish you luck.”

And then I walked away.

An hour later the article came out.

Set aside the fact that Trace Lysette, a former sex worker whose pampered male costar gleefully told her he wanted to “attack [her] sexually,” is obviously a much more accurate symbol of transness than wealthy professor emerita Maura Pfefferman ever was. What’s truly shocking is that, presented with the opportunity, and I’m being completely serious here, to lie, or at least fudge the truth, Soloway once again nukes herself without even noticing, gravely comparing a sexual harassment victim to the fictional character Fredo Corleone from The Godfather Part II, the Oscar-winning 1974 crime film at the end of which, if you’ll recall, Fredo was literally executed for betraying Al Pacino.

The only conclusion to be drawn from this very bad book, which puts the “self” in “self-aware,” is that Jill Soloway has an unstoppable, pathological urge to tell on herself. In fact, it’s all she’s ever done. If autofiction like Girls, Louie, or Transparent teaches us anything, it’s that there is no better disguise than one’s own face. Midway through She Wants It, while prepping three different Emmy acceptance speeches, Soloway wonders if she suffers from a “delusion of grandeur,” before dismissing the phrase as a diagnosis for “cis white guys.” “Is it delusional to try to suggest to yourself that it is okay to believe you might be magnificent when the world raised you to mostly admire men, to reserve grandiosity or genius only for them?” she asks.

If the question is, “Can women and queers be pretentious assholes?”, She Wants It holds the answer.