A Sandwich, a Tower, a Tree

Orit Gat

July 2, 2018

1. Sandwiches

It’s November 27, 2017. Like any other person who spends too much time in front of a computer, I’m reading live updates and analysis on the Guardian about Prince Harry’s engagement to Meghan Markle. Between reports on the couple’s first BBC interview and Jeremy Corbyn congratulating them is a quick write-up asking, “Will Trump be invited to the wedding?” considering that Markle has been critical of him and “branded him misogynistic.”1

What caught my eye is not the question nor Markle’s choice of words, but the Guardian’s illustration: a thumbnail-sized portrait shows Trump—the sleeves of his suit too long, tieless, the top button of his white shirt undone—pointing at a basket full of saran-wrapped baguettes. I take a screenshot and save it, file name: WHY.

Once I start digging into this question, I realize there are two answers: the first is short, the second is the subject of this essay. To open with the short and simple: in November 2017, an image editor for the Guardian bought a very recent photograph from AP to accompany that brief discussion of Trump. The photograph is cropped; in the original you see the back of a uniformed man in front of Trump, and clock an exchange. It’s from a photo of Thanksgiving Day, when Trump and wife Melania handed out sandwiches to U.S. Coast Guard members on duty over the holiday.

Breitbart posted the photograph alongside a report on the White House annual Thanksgiving remarks. Other outlets used the photograph in the days that followed—often, like the Guardian, for articles that were not about Trump’s holiday plans, sandwich recipes, or the relationship between the administration and the Coast Guard. What Yahoo! did and the Guardian didn’t was use a caption that explains the situation: “President Donald Trump prepares to hand out sandwiches to members of the U.S. Coast Guard at the Lake Worth Inlet Station, on Thanksgiving, Thursday, Nov. 23, 2017, in Riviera Beach, Fla. (AP Photo/Alex Brandon).”2 The Guardian caption simply reads, “Donald Trump.”

2. Answer #2: Image Editing after Trump

Over Christmas in the 1980s, if you were a businessman-slash-serial-killer, Donald Trump’s yacht is where you’d want to be. In American Psycho, Patrick Bateman’s to-do list includes getting an invite to Trump’s holiday party. Looking back at the 27-year-old novel it’s shocking to see how the image of “Donny” in that book has changed, how recent that change has been, and how it was always coming. In 1989, in Esquire magazine, Nora Ephron wrote, “[L]ook how happy he is in his Trumphood; look how merrily he floats in his Trumpdom; look how brightly he wallows in his Trumpness. You just can’t imagine him whining or complaining about any of it.”3

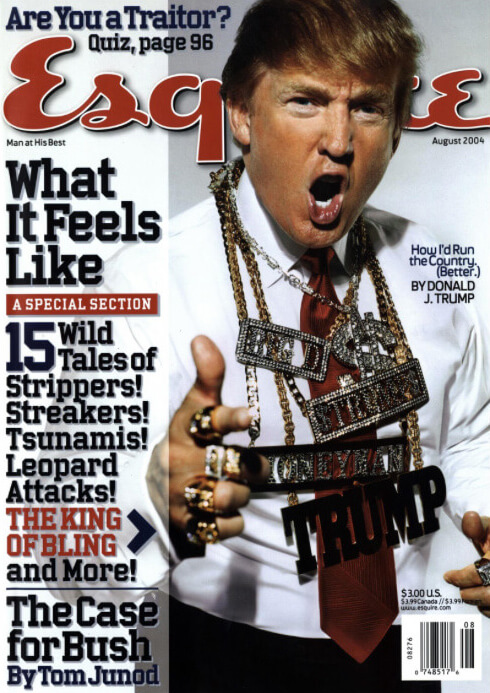

Again in Esquire, on the cover of the August 2004 issue (the cover line—ironically or prophetically—was, “How I’d Run the Country (Better.) By Donald J. Trump”4) Trump is bling-bedazzled: rings on his hand, pointing toward the camera; statement chains around his neck with pendants reading “TRUMP,” “MONEYMAN,” “BIG D,” and around his neck a dollar sign in gold and precious stones (or fakes, and does it matter?). He’s wearing a red tie; a white shirt stretches on his growing belly. His face, mid-shout, screams something between go-get-’em confidence and Bateman with the chainsaw. Depending who you ask.

Who you ask has become a central question in an age when, after the presidential election in 2016, Time magazine chose Donald Trump to be its Person of the Year. They ran a portrait by Nadav Kander, a British photographer known for his Baroque style: dim light, dark background, shadowplay, and strong color contrast. On the cover, Trump faces away from us in a nineteenth-century style armchair. He is half-turned toward the camera, his face in three-quarters, hands resting atop each other. He casts a shadow on the wall behind him and exudes the self-satisfaction of the winner. The cover line: “Donald Trump: President of the Divided States of America.”

The shift in Trump’s image from shiny success to dark ruler is a study in self-presentation that—like a mirror of the Trump presidency—never conforms to any accepted notion of the presidential image. (The word presidential newly loaded: “My use of social media is not Presidential - it’s MODERN DAY PRESIDENTIAL.”5) Of course, back in 2004, when he stood in front of the camera in gold chains emblazoned with his name, Trump knew exactly what he was doing.

The Apprentice began airing on NBC that January and Trump was selling a specific brand of tycoon, an image of success in golden excess that is immediately recognizable, so that no TV viewer would ever doubt the worthiness of the first-prize in the reality show: a contract to run one of Trump’s companies. The gold was there to distract the audience from Trump’s four bankruptcies. He sums it up in his 1987 bestseller (he doesn’t call his books books): “I play to people’s fantasies.”6

The bling seems dated now. In 2004, both Trump and Esquire had something to gain from it: attention. Today, the relationship between image and the construction of persona is not as transparent. The circulation of images of the president is calculated, as always, by both the White House and the media. When the Guardian publishes the sandwich photograph, or when The Hill—which so regularly chooses unflattering images of Trump that scrolling down its Twitter feed is an unforgiving mass of facial expressions and awkward poses—chooses those images, there’s a wink to readers: “we’re on your side.” It’s a news cycle that confirms its readers’ beliefs. That offers comfort by reinforcing their views.

3. It All Started on the Internet

Maybe we share these images because we are anxious.

A stack of issues of Der Tagesspiegel made the rounds online before the election. On the front page is a photo of Donald Trump, and the issues are piled in a way that stretches his image, elongating his mouth as he orates. It was actually an ad campaign for the Tagesspiegel by Berlin advertising agency Scholz & Friends. It won a Gold Lion in the Cannes Lions International Festival for Creativity. Though it was a print campaign, the image was widely shared across social media because it was so quickly legible: it dehumanizes Trump by honing in on his recognizable attribute—bombastic rhetoric. Again: “The final key to the way I promote is bravado. I play to people’s fantasies. People may not always think big themselves. but they can get very excited by those who do. That is why a little hyperbole never hurts. People want to believe that something is the biggest, the greatest and the most spectacular.”

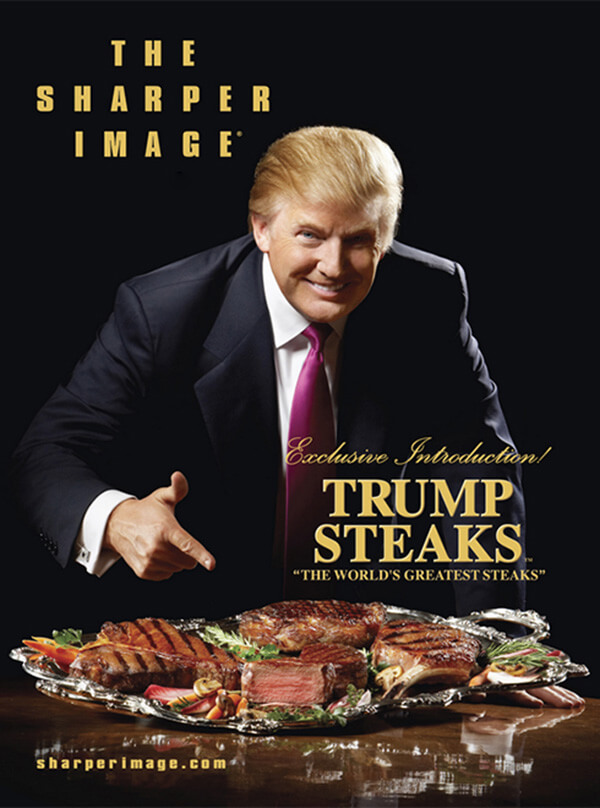

The Trump candidacy and presidency have been a case study in the use of vernacular imagery in the internet age. A red baseball cap. Red ties. A tower. The haircut. The hand gestures. Trump has built an image of success that could be expanded endlessly: Trump Steaks could cost $999 at the Sharper Image; the Trump Tie Collection is still available from the Trump Store, see “merchandise” on the Trump organization’s website. The gold signs on his building, the business that was always referred to as an empire—Trump has always presented himself as a king.

When he was up for election, he built a popular image as a man of the people, but never let go of his monarchical air: Trump was the man of the people who selected him to rule them. And his ideas of power, of a right to rule, are clearly more dated than democratic; in March 2018, at a luncheon on Trump’s estate Mar-a-Lago, he talked about Chinese president Xi Jinping’s consolidation of power, saying he was now “president for life,” and then: “I think it’s great. Maybe we’ll want to give that a shot someday.”

Walking up to Trump Tower as part of the many demonstrations that took place after the election, I remember thinking it was like a scene from a science fiction or cyberpunk movie: a mass of people walking through a cold, dark city, toward a towering glass-and-steel building with the name of the ruler imprinted in gold lettering. What reads like the seat of the empire to those who want to see it “great again,” embodies the history of anti-authoritarian films and writing to others.

4. What You See When You Look

An older man straightening a younger man’s lapel. The young man looks at him, smiling, a dimple in his cheek. What to read in his eyes? It’s not trust, nor admiration.

April 2018. Trump is standing by Emmanuel Macron, the 40-year-old French President who assumed office less than a year beforehand and was on his first state visit to the United States. In the video, Trump gushes about their connection: “Mr. President,” Trump says to Macron without directing his body language to his European counterpart, “they’re all saying what a great relationship we have, and they’re actually correct. It’s not fake news…we do have a very special relationship. In fact, I will get that little piece of dandruff off,” he says, then brushes Macron’s suit with his finger. What to read in Macron’s eyes? He is caught mid-smile. His surprise, his restraint.

The state visit produced a burst of awkward photographs. Here is Trump holding Macron’s hand as he leads him somewhere in the White House courtyard. There is Trump hugging him, only one of Macron’s eyes visible through the expanse of the American’s shoulders; he looks directly at the camera but his gaze wanders off. He can’t maintain eye contact. Trump relies on narrative. His image is based on a narrative of success, his politics on an idea of action (Trump uses the language of business and construction—building a wall, jumpstarting an economy, knowing well that his voters associate his paraded success as a businessman with his achievements as a politician).

Unintentionally, though, photographs catch the holes in these stories. In pictures, Trump is often caught in an unflattering light or in an inexplicable gesture. In two-dimensions, the bravado can’t be sustained for that extra second that persuasion requires. And the result always feels like it exposes an inopportune truth.

The French state visit culminates in a ceremonious planting of an oak tree on the White House lawn. Macron’s gift to Trump came from Belleau forest in northern France, where thousands of American soldiers were killed during World War I. As with any agricultural or horticultural item brought into the country, the tree needed to be quarantined as an environmental protective measure. But Trump, Macron said, insisted on a ceremonial planting of the tree before it was taken away. The photographs from this event are so indecipherable, disturbing. Twitter users had a field day with “they’re burying the body” style comments.

In suits, with their wives behind them, the two men never look at the camera. They are focused on a task that shouldn’t be very hard—overdoing it like only a symbolic, futile gesture can be overdone. The symbolism is meant for the camera, but the photographs failed the two men: they expose something that was there all week, the awkwardness, the performance to the cameras. (Also, it really does look like they are burying rather than planting.) Some websites called the two leaders’ relationship a bromance. Like a kissing scene in a romantic comedy, though, sometimes the hesitance shows through. The plotline fails.

When the tree was dug up to be taken to quarantine, Time wrote that “a pale patch of grass now covers the spot.”7

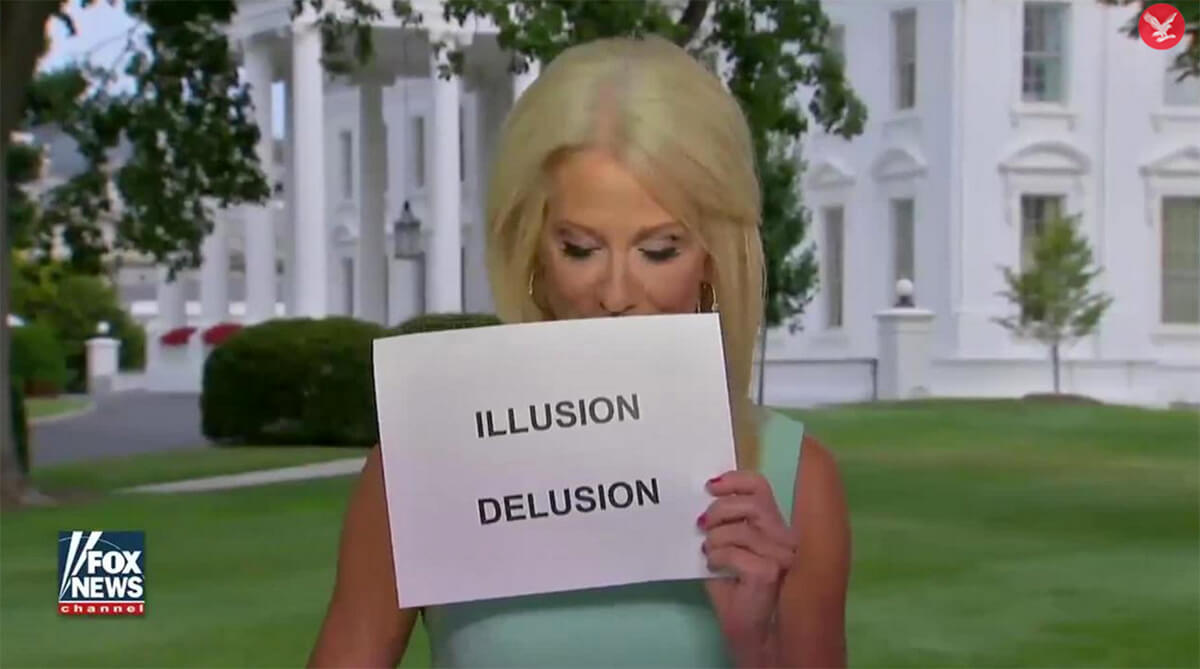

5. Another Note on an Illusion, or Saying It Like It Is

July 2017. On Fox News, Trump advisor Kellyanne Conway used flashcards reading ILLUSION / DELUSION to explain the Trump-Russia plot. Time called it “full on Sesame Street.” Here’s the narrative: after exploring what Conway thinks is an illusion (or a delusion, to keep her rhyme structure), she reaches the CONCLUSION, which is the word “collusion” with a big red X on it. I take a screenshot, again, and I see a new humanism in this moment, which objectively I know qualifies as a worrisome dumbing-down of the American public. In my screenshot, Conway’s eyes are lowered, presumably to grab the punch-line card, but the frozen frame conveys a Sphinxlike moment: her eyes downcast, her mouth is moving. Is she smiling to herself at her schoolteacher wordplay? Is she ashamed?

I produced an image of another person, with all the complexities of other people. There’s something sad about it. There’s also a message to power: It’s a single freeze frame that shakes up the idea of representation, of l’état, c’est moi. If an advisor to the president can’t even protect the president’s adult son from charges most American can’t even understand without exposing a visual soft belly—herself, her simplistic didactics—how is the image of this presidency made?

6. The Image of Power

It’s December 2017. I’m on the New York Times homepage, waiting for a live broadcast of the speech recognizing Jerusalem as the capital of Israel and assuring that the United States embassy will be moved from Tel Aviv to the contested city. Before his speech begins, the livestream is on but the frame is of an empty space in the White House. There’s a table, a Christmas tree in the corner, but that’s it. Soon the camera will zoom in on a podium flanked by an American flag and the seal of the presidency. Soon there’ll be speech and action, a muted Mike Pence in the background standing just ahead of a portrait of George Washington and a Christmas wreath on the fire escape.

But watching the empty room, I feel saddened. It feels so abandoned. I take a screenshot, and recognize that sadness is a precursor of the fear and anxiety in front of power: the assertion of power in the podium, the flags, the portrait—and the assertion of culture in the Christmas decoration. Every detail here is legible, like a red cap, like a flag pin on a suit’s lapel.

7. Building and Breaking an Image

“The most important aspect of my work is creating a historic visual archive of this Presidency,”8 writes Pete Souza, the Chief Official White House Photographer under President Obama. The official position of a photographer who documents behind the scenes of the presidency only began in John F. Kennedy’s time (with photographs of the young president and his toddler kids “forever expanding our idea of a modern president”9), though placing an emphasis on controlling the image of the president is famously exemplified in the Secret Service’s control of the photographs taken of Franklin Roosevelt, who wasn’t allowed to be photographed in his wheelchair.

The president is an icon. Like saying Washington to mean the United States government, like referring to a dollar bill as a “George Washington.” The photographer Edward Steichen made the most compelling and succinct case for documenting the history of the presidency in photography. Steichen, who was MoMA’s curator of photography, said to Lyndon Johnson: “Just think what it would mean if we had such a photographic record of Lincoln’s presidency.”10

Of course, LBJ already knew that: only one image exists from his inauguration: LBJ, aboard Air Force One, following the assassination of President Kennedy. He is standing, his hand on the Bible, his back bent. Johnson is so tall the plane seems tiny, as do his wife and Jackie Kennedy, still wearing that pink dress stained in blood. The photograph is black and white, but we all know the dress is pink. It’s an image forever imprinted in the American memory. The widow of his predecessor standing next to him, his towering figure—the one photo confirms his position, his right to rule.

The telegenic Trump is suspicious of the camera, as if it’s catching him in the act. But television has not been much kinder to Trump: In a profile of actor Alec Baldwin related largely to his performances as Trump on Saturday Night Live, writer Chris Jones describes: “For the next shot he pulls on an ill-fitting suit and too-long tie, and he watches as that same wig is placed on his enormous, groomed head, and he mangles his eyes and pushes out his lips, this tired man made beautiful made ugly. It’s an unsettling transformation to watch. It’s almost as though Alec Baldwin, before he can become Donald Trump, must first become the best version of Alec Baldwin, and then ruin him.”11

Baldwin’s portrayal of Trump has won him and Saturday Night Live many accolades in a time when comedy is a frontline of the culture wars. Jones’s article spends much time on the wig Baldwin wears when portraying Trump. The metonymy is obvious not only since images of Trump’s hair are so ubiquitous but because the image of the presidency is already so symbol laden. And because legible images can quickly be stripped down.

Power is asserted visually, and analysis—of images and their widespread distribution as a marker of anxiety—serves only to decode it. We read these images of Trump incredibly quickly, which allows for an easier, less anxious view of contemporary politics. In Camera Lucida, Barthes quotes Kafka: “we photograph things in order to drive them out of our minds.” The creation and sharing of quick (and quick-to-travel) images reveals something about the real, the present and our relationship to it: we want it simpler.

- Patrick Greenfield, Jamie Grierson, Haroon Siddique, “Meghan Markle and Prince Harry’s first TV interview in full – video,” the Guardian. See https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/live/2017/nov/27/prince-harry-and-meghan-markle-engagement-live-updates?page=with:block-5a1c25047e54bf066ccdc9f0#liveblog-navigation

- Jill Colvin, “Trump calls for crushing terrorists with military means,” AP syndicated article on Yahoo! See https://www.yahoo.com/news/trump-calls-crushing-terrorists-military-means-074648459--politics.html

- Quoted in Alex Belth, “That Time Tom Junod Predicted the Political Ascension of Donald Trump,” Esquire (January 5, 2016). http://classic.esquire.com/editors-notes/that-time-tom-junod-predicted-the-political-ascension-of-donald-trump/

- Esquire reran the 2004 text on their website in September 2016: “Funnily enough, what he said 12 years ago helps us understand his (il)logic today.” See http://www.esquire.com/news-politics/a37230/donald-trump-esquire-cover-story-august-2004/

- Trump tweeted this as defense against critics of his Twitter habits in July 2017: https://twitter.com/realDonaldTrump/status/881281755017355264

- Tony Schwartz, Donald J. Trump, The Art of the Deal (New York: Ballantine Books/Radom House, 2015 [reprint]), 58.

- See “Now We Know Why the Tree That Donald Trump Planted on the White House Lawn Suddenly Disappeared,” http://time.com/5259560/macron-trump-tree-disappeared/

- Pete Souza, “Introduction,” in John Bredar, The Presidents’ Photographer: Fifty Years Inside the Oval Office (Washington DC: National Geographic Society, 2010), 13.

- Bredar, The Presidents’ Photographer, 52.

- Souza, “Introduction,” 14.

- Chris Jones, “Alec Baldwin Gets Under Trump’s Skin,” The Atlantic (May 2017). https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2017/05/alec-baldwin-gets-under-trumps-skin/521433/