Thresholds of Visibility

Siobhan Leddy

February 26, 2018

You can’t beat the primitive, electric thrill of unearthing a secret, as breathtakingly depicted in Michelangelo Antonioni’s 1966 masterpiece, Blow-Up. A fashion photographer, after secretly photographing a couple in the park, notices something strange in the developed images. Curious, he enlarges various sections, zooming into their black and white grains. Concealed in the bushes is the blur of a man’s face, and a gun pointing directly at the couple—or could that just be leaves?

We see the photographer filling in the gaps, constructing a narrative from fragments. He runs around the studio, his exhilaration palpable. “Something fantastic has happened!” he tells a friend on the phone, “Somebody was trying to kill somebody else!” He then returns to another magnification, another blow-up, from a photograph taken moments later: in it we see a body, supine on the grass. Blowing it up once more, the body becomes an indecipherable smear.

Particles, if small and plentiful enough, take on the appearance of a whole. This is true for drizzle, which from afar resembles continuous sheets of fog. It’s true for your own body, made up of cells and atoms. This is true for photographs. Even if we know a photograph is little more than huddled pixels, we still suppose that it is somehow whole, a smooth and exact rendering of a single moment snatched from reality. We talk about seeing “the whole picture,” which of course we might, but it’s a picture all the same. This optical illusion can lead to mistakes.

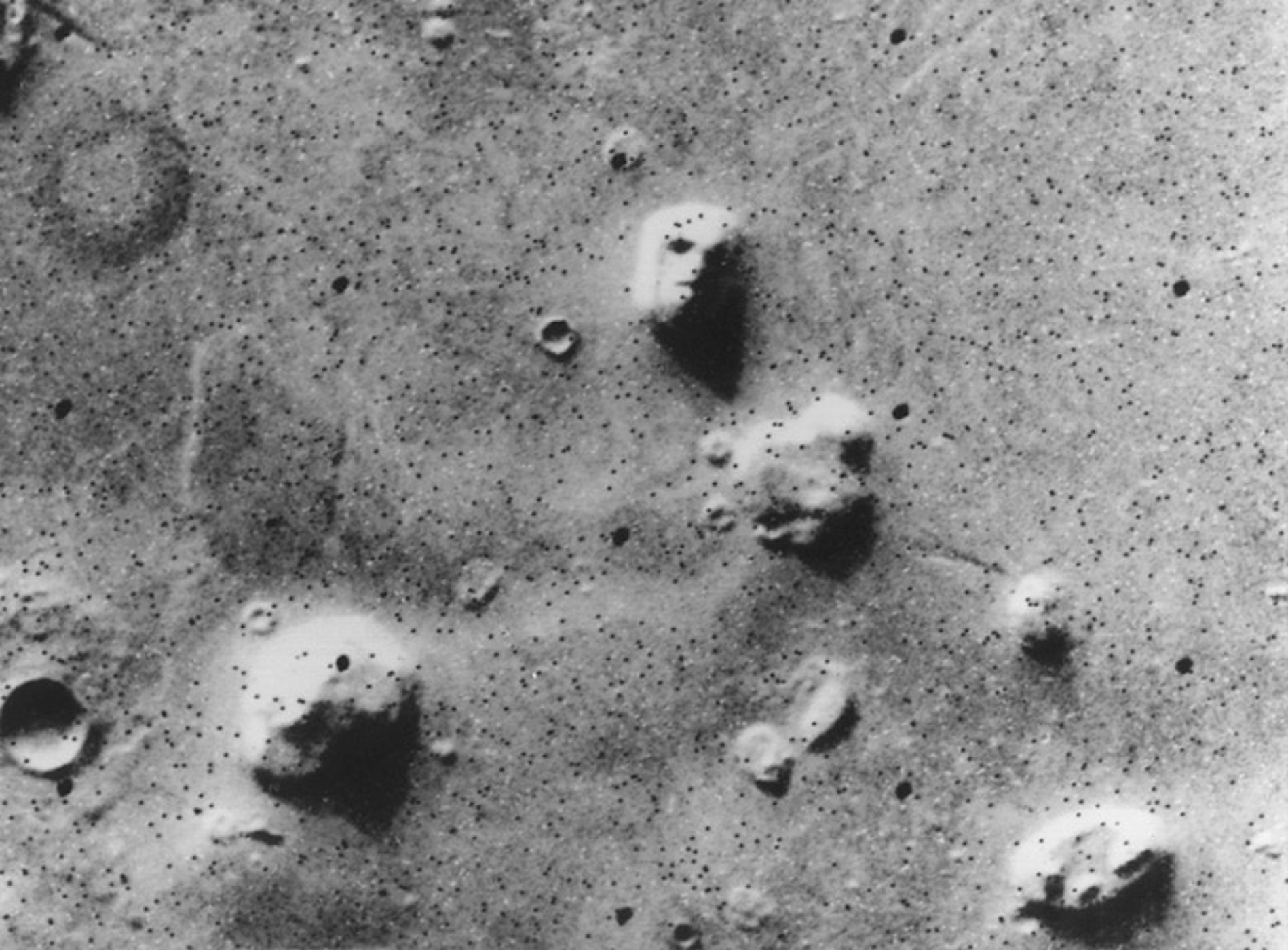

In 1976, the Viking 1 Orbiter transmitted its photographs of Mars’ surface back to Earth. One seemed to show, very clearly, the likeness of a human head. Its deep eye sockets and impassive mouth were reminiscent of a Greek chorus mask. Some believed the face offered definitive proof of life on the red planet, and evidenced a conspiracy covered up by government elites. But, as can be the case with conspiracy, the problem was one of resolution: 20 years after the Orbiter mission, a higher resolution camera revealed the face to be a plateau of rock. Back in 1976, those details fell under the resolution threshold, and were consequently invisible. On Earth, we were free to fill in the gaps with anything we could imagine.

There will always be intervals between pixels; or, to use a cliché, you can’t have a presence without an absence. Low resolutions mean greater intervals, which in turn means more work for the imagination. For whatever reason, we reject ambiguity, instead preferring to swaddle ourselves in comfortable certainties. We unconsciously straighten question marks into exclamation points: Oh, look, there’s a face! This joining-the-dots is known as pareidolia: the act of seeing patterns in random visual data.

Etymologically rooted in the Greek para, meaning beyond or instead, and eidolon, meaning image or shape, pareidolia is why we might see George Washington in a chicken nugget. Why Mother Teresa appears in a cinnamon bun. Why the Shroud of Turin is revered to this day. Acheiropoieta—religious icons that spontaneously appear—are some of the most powerful ambiguous images, as they testify to the existence of miracles and God. In visual art, pareidolia can be a generative force, helping our imaginations leap beyond the material in front of us. Leonardo da Vinci wrote that a painter might find inspiration in “walls spotted with various stains or with a mixture of different kinds of stones.” How remarkable it is to be moved by these things, to experience a luminous epiphany from something as banal as a blob of toothpaste in the sink.

Conspiracies, too, harness that same imaginative power. Much as a complete image is constructed from divergent pixels, conspiratorial thinking pulls together disparate and free-floating units of information, organising chaos into narrative. Always operating under conditions of lack, conspiracy is built on only the smallest fragments of evidence. The vid of evidence is rooted in the Latin “to see,” but conspiracies always move in the shadows, beyond the threshold of the visible. Conspiracies can, of course, be dangerous; their adherents link vaccines with autism, or see a president’s skin color and conclude: he’s not one of us. (The latter, as Trump’s ascendency attests, wields alarming power.)

But conspiratorial thinking is also a methodology, one that stands in opposition to what social media theorist Nathan Jurgenson describes as “factiness”—the liberal taste for facts and data, which, paradoxically, obscures broader realities. The consumption of facts, information, data and probabilities soothes the part of us that wants us to feel informed, without ever really increasing understanding of the world around us. But, if “factiness” is a pseudo-science, conspiracy is art: improvisational, imaginative, peculiar. If removed from its right-wing context (where facts were long ago discarded), could conspiracy become politically useful for the leftist imagination? Could it help us to think beyond the immediately self-evident?

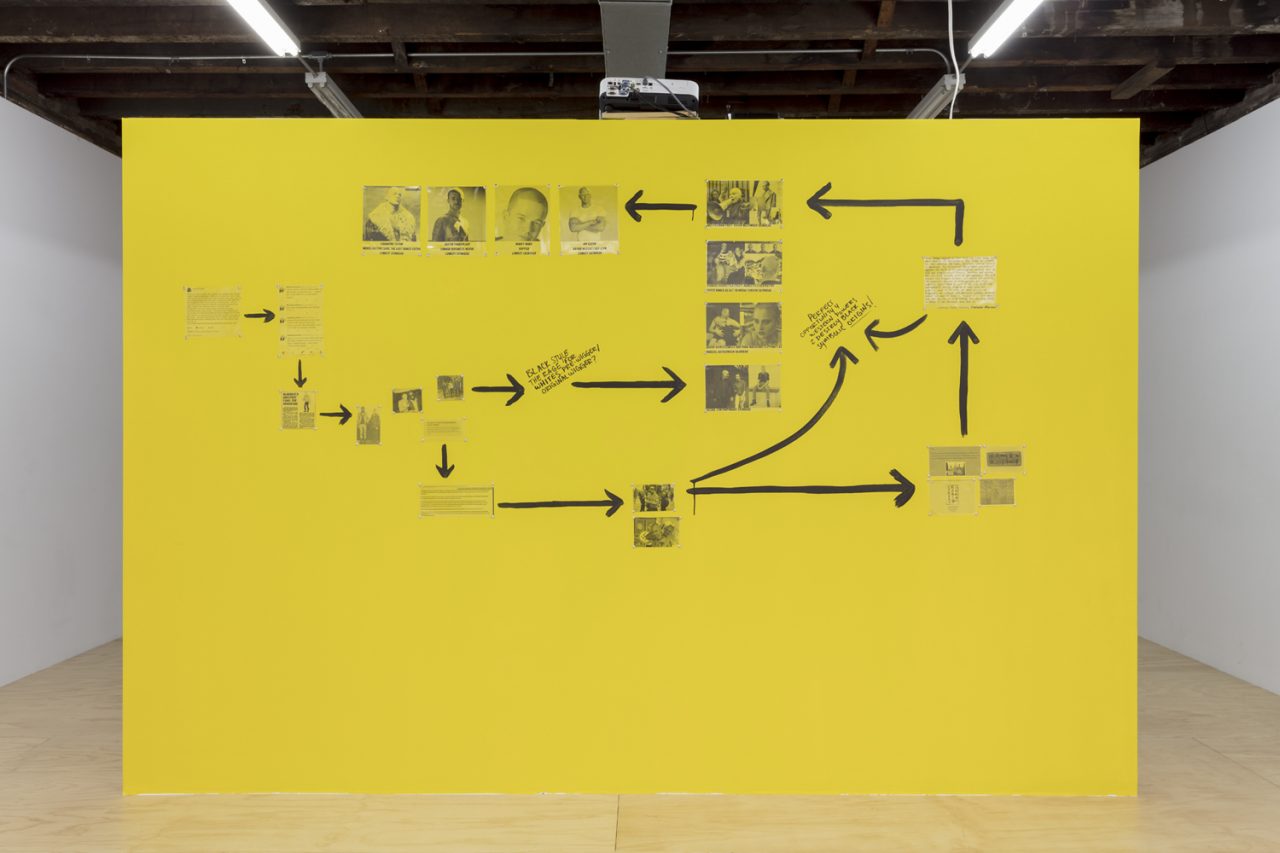

Juliana Huxtable prods at these wounds. Her 2017 solo exhibition at Reena Spaulings Fine Art, A Split During Laughter at the Rally, explored the contradictions and complexities of conspiratorial thinking. Theories were pulled from the margins and into the gallery space, free-associations so diffuse they could barely be contained. “Untitled (Wall)” (2017) resembles the wall of a frantic detective looking for clues, with its print-outs of skinhead typologies (Channing Tatum = “lowkey skinhead”) and thick black marker arrows sketching out a potted history of white supremacy.

“Feminist Scam” (2017), meanwhile, is a hot-pink graphic poster evocative of Emory Douglas’ agitprop, emblazoned with messages warning of the dangers of feminism to black masculinity. Rather than recoil from this skewed logic, Huxtable warily peeks behind the curtain. She believes conspiracy to be a product of disenfranchisement, and asks what the role of that feeling could be in such a chaotic present. “If we engaged everyone in a conspiracy it would all devolve into a base nothingness,” she has said previously in an interview, “and I think that nothingness would be more of a unifying point than trying to navigate the political reality that currently exists.”

George Widener is also looking for a unifying point. The artist is unusually perceptive when it comes to dates—“As a seven-year-old,” he once wrote, “I could have told you that July 4, 1916 was a Tuesday”—and he speculates entire numerical worlds from almost nothing. Using magic squares (a number puzzle not unlike Sudoku), calendars and charts, Widener creates temporal maps that collapse past, present and future in highly complex ways. After a period of forced mental health detention, he experienced a “vision of Time as a monolithic crystalline structure.” He felt newly attuned to the subtle shifts of time, and began translating them into intricate drawings—visualized information that was as baffling as it was striking. Widener’s “Magic Square 12-21-2012 (Conspiracy)” is one such depiction.

The date refers to the Mayan’s predicted date of apocalypse, and Widener uses a grid of twenty-five orange numbers to mathematically riff on the event’s likelihood. Widener himself is relegated to the fringes as ‘outsider artist’ (despite showing at London’s Hayward Gallery and Berlin’s Hamburger Bahnhof), but he rejects the label. He insists that his art is not visualizing some private worldview, but rather that the bottom of the barrel, the discarded ideas, may hold some common truth. Conspiracy, like any marginal politics, is an insistence on that which lies slightly out-of-sight. It inhabits the cracks, wide-eyed and belligerent, telling a story nobody believes.

Insistence is also the job of forensicists, who must tease out fact from apparent paucity. Take an early project by Forensic Architecture—an interdisciplinary research group made up of architects, artists, engineers and others—which made use of satellite imagery to detect illegal drone bombing activity in Waziristan, Pakistan, an area that has been bombarded by thousands of US-drone strikes in the years since 2004. It was, and still is, notoriously difficult and dangerous to enter the region, and harder still to photograph up-close. Few reporters even attempt it. “When you…cross past certain areas from mainland Pakistan,” journalist Wajahat Khan told Al Jazeera last year, “well, it becomes a free-for-all. Your safety is not guaranteed.”

Forensic Architecture researchers sought to create a record, a map, of drone attacks, which may later serve as evidence of war crimes. Since on-the-ground work was out of the question, the researchers turned to publicly accessible satellite imaging. The resolution of these images is continually improving for private and government data, but for the public it sits at around 50cm per pixel—that’s much greater than the size of a hole left by a missile. The image, in this sense, has failed, too incomplete to speak any kind of prima facie truth. We cannot know for sure how many war crimes are concealed inside pixels. It is only when placed into dialogue with other images, witness testimony, or footage smuggled out by local civilians, that anything resembling evidence begins to emerge.

Of course, sometimes the inverse may be true: we may be too visible. Blackness, as many activists and writers of color have noted, becomes hypervisible in white spaces. Femininity, too, is often too visible: as a teenage girl, I used to wonder what it would be like to walk down the street as a man. Would I become invisible? (It’s sad to think that this is how I once imagined masculinity, as a kind of superpower.) To develop an awareness of the power structures that govern us can even feel paranoid at times; but as the old adage goes, just because you’re paranoid it doesn’t mean they’re not out to get you.

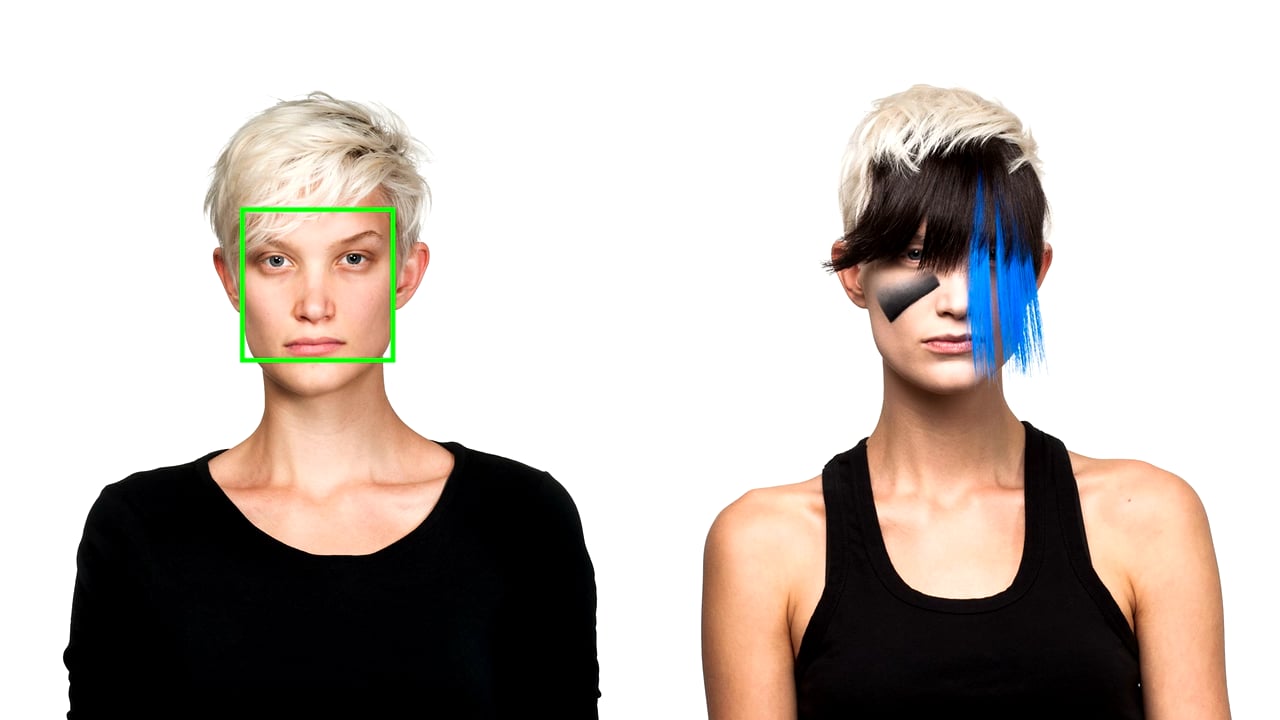

Nearly all of us today are hypervisible to algorithms. The width between our eyes and the length of our foreheads become digital patterns, sets of data. A digitized phrenology. Antonioni’s suspicious fashion photographer has been replaced by innumerable strings of suspicious code. And suspicious they are: local governments in China are already using Face++, an advanced facial recognition technology, to identify suspected criminals. The rest of the world, if it hasn’t already, will likely follow suit.

But algorithmic seeing is also predisposed to misunderstanding. Identity is reduced to data particles that can be blown into chaos at even the slightest wind. Take Adam Harvey’s ongoing CV Dazzle, an invisibility strategy for facial detection technologies. The artist daubs paint onto cheeks and foreheads to “break apart the continuity of a face.” Thrown off the scent, the algorithm no longer sees what is really there — although, it should be noted, the designs are bizarre enough to attract enough human attention in its place. This is not so much invisibility, but rather a mode of visibility that the algorithm cannot understand.

When the human eye sees an image it does not understand, we furnish it with meaning through language. Take, for example, a painting by Vorticist painter Wyndham Lewis. At its center, imposing from above, is a jagged tower of slabs in orange, black and blue. It’s almost ugly, goading. The tower seems hardened and alive, like an impossible skyscraper. However, its title, “Portrait of an Englishwoman,” shifts it from the architectural to the human. Annotations have a long and rich history in art, and provide interpretive clues for more abstract works. Were “Portrait of an Englishwoman” to be called “Regent’s Park,” for instance, it would be read differently. The painting could be: a gun, a corpse, a murder caught in the act. Perhaps its meaning changes again with more words, when you learn that Lewis was an early advocate of National Socialism. That for the cover of his 1931 book, Hitler, he sketched out three swastikas in the same Vorticist style.

Abstract paintings like Lewis’ are given meaning from outside of itself: title, criticism, biography. They are partial, particulate. But aren’t all images abstractions? Let the work speak for itself!—an outrageous request. No image is an island, and it is instead bound up with the constellations of words, images and histories that exist in the world around it. Think of the Waziristan satellite images: alone they fail to represent anything at all, but in dialogue with other images and witness testimony they may be transformed into evidence. Or algorithmic face-detection data: benign alone (it’s just code, after all) but ominous in a context of legal discipline and punishment.

If an image is always ambiguous, then who is allowed to give it meaning? What voices, with what kind of power, have authority to make an image speak? The answer is almost too obvious. As Laura Kurgan notes in Close Up at a Distance, think of Colin Powell who, speaking at a UN press conference back in the early aughts, asserted that a satellite image certainly, unequivocally, proved Iraq was producing weapons of mass destruction. “Chemical munitions bunker” reads the authoritative label, pointing at—what? A warehouse? A factory? It makes Blow-Up look oddly prescient. But, unlike Antonioni’s photographer, unlike the conspiracy theorist, Powell had the full weight of a political class behind him. He was able to make an image appear whole, seamless, when it was nothing of the sort.

The world has changed a lot since 2002, of course. Powell was delivering his image-narrative, buoyed by power, to a less suspicious world. The idea that images and facts are open to manipulation has gone mainstream of late, thanks to zeitgeist-y phrases like “post-truth,” “alternative facts,” and “fake news.” Now is a time of sickly conspiracy, of obscure ideas and fertile absences. Conspiracies are now kingmakers. This comes at a cost—the furious white nationalist thrives in the absences as much as, say, Widener’s pluralistic time-maps. But conspiracy, or whatever else it should be called, can also be productive and playful and strange. Here lies something beyond evidence or “factiness”: alternative methodologies that reach into the forgotten, gloomy darkness. The absences of fact could also end up making room for other things.